Fig.

1 - Bogdan Bogdanović, Monumento del fiore, Jasenovac, Croazia, 1966

PH Alberto Campi.

If there is a place where East and West touch, collide, and influence each other, it is the Balkan Peninsula. Predrag Matvejević defines it as a «middle region [...] a confluence between East and West, a crossroads between East and West, a dividing line between Latinity and the Byzantine world, an area of Christian schism, and a frontier of Christianity with Islam». This diversity has often resulted in conflicts, serving as a significant obstacle to garnering global attention, both culturally and in terms of the visibility of artistic and architectural production. This is due, in part, to the interpretative stereotype of the Balkans as a political and cultural «in-between» (Mrduljash, 2012) and the perception of the Balkan Peninsula as the «semi-periphery» of an industrialized West. Consequently, the architectural and urban uniqueness of the region has been consistently underestimated.

FAMagazine's monographic issue offers a reflection on the role and singularity of architectural production in the cities of the former Yugoslavia. The modernization process that began after the Second World War remains a largely unexplored chapter with its intricacies and specificities. While not claiming to provide a historical reconstruction, the various contributions aim to interpret the often-overlooked events and projects in Balkan cities that still hold significance for the contemporary condition today. In this regard, this work serves as a tool for repositioning the discourse and as an opportunity for debate and in-depth analysis, with a particular focus on the 1960s and 1970s.

This historical era has recently attracted growing attention from scholarly studies and research, introducing a new lens through which to view a wide-reaching cultural and theoretical phenomenon. It is intricately entwined with diverse national contexts, and its architectural output has frequently been obscured by historiographical and political narratives, culminating in a negative portrayal and a prevailing sense of ‘disdain‘ for these entities.

One of the early events that triggered a reevaluation of this period was the Brutalism symposium titled Brutalism. Architecture of the Everyday. Culture, Poetry and Theory. This symposium was organized by the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and the Wüstenrot Stiftung and took place at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 2012. It went beyond the typical historiographical approach of documenting the biographies of architects and their works. Instead, it set out to initiate a broader discussion on brutalist architecture as a manifestation of a «distinctive modernity». This unique form of modernity had the ability to capture and define, in an innovative manner, the ongoing transformations occurring in the Western world following the Second World War.

Around the same time, in Slovenia, the initiative Unfinished modernizations, between utopia and pragmatism commenced, marking the beginning of a series of seminars hosted at the Maribor Art Gallery. This undertaking unfolded over a two-year period, from 2011 to 2012, alongside an exhibition curated by Maroje Mrduljaš and Vladimir Kulić. This endeavor represented another pivotal phase in the ongoing exploration, with a specific focus on the architectural heritage of the former Yugoslav nations. It delved into the era spanning from the emergence of communism in 1945 to the eventual dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic in 1991. The architectural accomplishments of Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia were reevaluated through a fresh perspective, unburdened by the narratives of "socialist progress," and reintegrated into the broader context of global architectural history.

In a parallel effort, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York embarked on its own exploration between 2018 and 2019 with the exhibition titled Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980. This groundbreaking exhibition, featuring a rich collection of over 400 drawings, models, photographs, and films, spotlighted the pivotal role played by brutalist architectural production in Yugoslavia on the international stage. It underscored its exceptional nature, not solely in terms of quality and quantity but also due to the distinct interplay between a shared history and a collective identity within a multi-ethnic state. This state was marked by the coexistence of divergent needs and influences.

Simultaneously, the exploration of Yugoslavia's architectural heritage ran in tandem with the broader resurgence of Brutalism. This resurgence was exemplified by the exhibition SOS Brutalism. Save the Concrete Monsters!. This exhibition was supported by the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt (DAM) and the Wüstenrot Foundation of Ludwigsburg. This initiative also gave birth to an open-source digital archive, now housing an impressive catalog of more than 1,600 architectural works. The archive's mission extends beyond mere documentation, aiming to both showcase the vast expanse of brutalist architecture and raise awareness about the pressing need to preserve this colossal cultural legacy, presently endangered and facing severe degradation.

Even in the realm of social media, we are witnessing an increasingly prevalent trend in sharing photos and images of brutalist architecture. Modern communication tools have managed to accentuate previously unexplored aesthetic and formal values. The proliferation of Facebook pages, blogs, and hashtags — with approximately 481,000 Instagram posts featuring the hashtag #brutalism, along with tens of thousands of related variations — serves as tangible evidence of the renewed interest and evolving perception surrounding these architectural works. As Virginia McLeod contends in her work, the Atlas of Brutalist Architecture, she goes as far as to suggest that "Instagram will save the brutalist heritage".

In 2018, 99Files presented an exhibition and digital archive at the MoCa (National Museum of Contemporary Art) in Skopje. This initiative materialized through an international call, conceived by the Landscape_inProgress[1] Laboratory at the Mediterranean University of Reggio Calabria, functioning as an interdisciplinary observatory dedicated to preserving brutalist heritage. Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, which became closely associated with brutalist architectural culture during its post-1963 earthquake reconstruction, was chosen as a laboratory. The goal was to provide a fresh perspective on Balkan modernist and brutalist architecture, liberating them from the often negative connotations linked to ideological legacies while exploring alternative interpretive avenues for this crucial phase in architectural history.

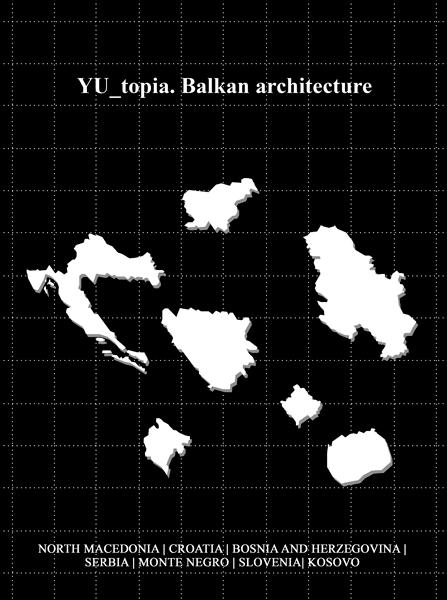

The monographic issue YU_topia: Balkan Architecture contributes significantly to this ongoing discourse. It invites readers on a journey through the cities of the former Yugoslavia, a region marked by experimentation and endeavors at modernization. While these cities, including Zagreb, Ljubljana, Sarajevo, Belgrade, Skopje, Pristina, and Podgorica, no longer share a unified political reality, they still offer valuable insights into a historical phase deserving reconsideration within the international architectural dialogue.

In an effort to dispel the notion that this region lacks its architectural identity, the various contributions within this issue illuminate the rich cultural dynamism and the pivotal role that architectural projects have played in different national contexts. These projects have often succeeded in conveying a shared architectural language while introducing distinct and original interpretations.

Moreover, the increasing interest in this historical phase prompts a reflection on the contemporary role of preservation efforts for a heritage that is "in danger of extinction." This perspective aligns with the ethical values of heritage preservation, not merely its aesthetic aspects. Such contemplation is essential, particularly in the Balkan context, where architectural and urban production is intrinsically tied to the historical and political events in the former Yugoslav countries. Here, architectural and urban developments serve as visible expressions of the «ruptures» (Kirn, 2014), interruptions, and subsequent re-beginnings.

This research is crucial not only to overcome the current state of neglect but also to highlight the unique aspects of this architectural production. In many cases, these aspects remain incomplete due to the often unrealistic objectives of self-managed socialist modernization programs and the challenging technical and economic conditions of a predominantly rural region heavily affected by war.

Tito's visionary leadership played a pivotal role in accelerating architectural change. His push for an architecture liberated from the constraints of Soviet socialism aimed to identify Yugoslavia's uniqueness within the new political and social landscape. Tito initiated an ambitious program of urbanization and industrialization founded on an egalitarian utopian vision. This vision was rooted in the ideals of self-management, where the working class played a central role in decision-making and production phases.

Architects embarked on a new trajectory during this period, as exemplified by Vjenceslav Richter's project for the Yugoslavian pavilion at the 1958 Brussels Universal Exhibition. This project showcased innovation through structural experimentation, signaling Yugoslavia's new direction on the international stage.

The use of concrete became emblematic of the modernization efforts in the construction sector, characterizing the reconstruction and design of infrastructure and new cities. In this context, the ethics of «As found [2]», representing an attitude of embracing reality, took on a different dimension. Here, the rough and textured surfaces formed a recognizable lexicon, no longer merely an expression of a desire to establish a concrete relationship with reality but also to symbolize the egalitarian utopian vision of Yugoslavia's self-managed socialism.

The cultural life of Yugoslav cities was vibrant and open to external influences, owing in part to the presence of young architects who, having received training abroad, brought back their experiences to shape the architectural landscape. Starting in the 1930s, this dynamic environment fostered a cultural climate that not only enriched architectural developments after the Second World War but also imbued the transformations with a strong connection to the local urban culture, firmly rooted in the international discourse.

This phenomenon was notably apparent in Ljubljana, where an architectural culture took root in the 1920s, forming what can be described as a "school" closely linked with Viennese universities. This academic circle revolved around the university founded by Ivan Vurnik (1884-1971) and Jože Plečnik (1872-1957).

The post-war reconstruction phase owed much to Edvard Ravnikar (1907-1993), a disciple of Plečnik. Ravnikar's work left a lasting impression, as he skillfully merged his master's classicist teachings with the brutalist influences of Le Corbusier, with whom he had collaborated during a stint in Paris.

The reevaluation of Revolution Square (1960-80), now known as Piazza della Repubblica, as discussed by Skansi and Campeotto, brings to light the unique nature of the Yugoslav experience, characterized by the interplay between modernity, urban layers, and regional culture. This complex square, characterized by its dynamism and permeability, establishes a strong connection with its surroundings through thoughtful ground construction, thereby reducing monumentality while still embracing international modernism.

This reveals a distinctive path taken by Slovenian architects, who draw inspiration from local traditions and reinterpret them using a modern architectural language. This approach is exemplified in the work of Oton Jugovec (1921-1987), marked by a delicate balance between modernity, rural and artistic heritage, and the region's architectural traditions (Pirina).

In Sarajevo (Gruosso, Zejnilović), a notable formalization emerged, blending egalitarian communist ideology with a "modernist" interpretation of the authenticity of local architecture. This transformation was largely attributed to a generation of architects who brought about a significant shift in the architectural landscape of the 1960s.

Bosnian architecture, influenced by Zagreb and Belgrade, found guidance in Juraj Neidhardt (1901-1979). He advocated for a «city on a human scale» and the establishment of a «Bosnian architecture hub», both rooted in a desire to reinterpret inherited architectural values through a fresh and modern lens. Neidhardt's urban and architectural solutions reflect meticulous research developed over years with Dusan Gabrijan (1899-1952) on Ottoman architecture. They recognized qualities treated by Le Corbusier in his Journey to the East. The writings of these two architects, now translated, reveal a fusion of references and analogies between Bosnian historical heritage and Le Corbusier's fascination with Ottoman and Islamic cities. For Neidhardt, who briefly worked in Le Corbusier's studio, modern architecture in Bosnia represented a reinterpretation of roots and a connection with Le Corbusier's ideas on urban and architectural principles.

The Sarajevo Olympic Games in 1984 played a pivotal role in the development of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The construction of entire sports facilities served as significant typological and architectural experiments, fostering expertise in environmental protection and tourism.

Zagreb (Pignatti) emerges as a vibrant city from economic, social, and cultural perspectives, where urban transformations and architectural innovations have mutually reinforced one another. Similar to Joze Plečnik's influence in Ljubljana, Viktor Kovacić (1874–1924) and Ernest Weissmann (1903-1985) in Zagreb have played pivotal roles in ushering in a shift towards modernity. They have been joined by a significant number of other architects who embarked on their careers with projects and structures marked by distinct innovative approaches.

Weissman's involvement in CIAM led to collaborative studies on the city, laying the groundwork for the modernization process and the New Zagreb Plan, inspired by Le Corbusier's principles. Conceptualized by Vladimir Antolic as a linear extension of the existing city across the river, this expansion unfolded through an open system of infrastructures, enabling the free arrangement of buildings, towers, and green spaces.

In the case of Belgrade (Ducanovič, Beretič), the capital of Yugoslavia, attention and debate were centered on the establishment of a new city, Novi Beograd. This new city was chosen to be built on a completely empty site, devoid of traces of the past, with the intention of creating a model for the "socialist city" based on innovative and egalitarian urban planning concepts. The post-war period in Yugoslavia saw a succession of proposals, starting with the more classical radial layout proposed by Dobrović and progressing to layouts inspired by Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse. These plans gradually moved away from monumentality and classical influences, embracing the use of reinforced concrete frames as guiding elements in building design. Chandigarh and Brasilia served as references for representative architecture, while the residential blocks, constructed from 1957 until the 1980s, adhered to the principles outlined in the Athens Charter. To achieve greater flexibility compared to the fixed reinforced concrete structural frame, prefabrication was adopted, significantly influencing the architectural language of the residential system.

Regarding the urban development of Pristina during the socialist era, there is limited documentation available. However, in recent years, the number of publications and awareness of the need for preservation have increased (Florina Jerliu).

Kosovo underwent a process of transformation and modernization aimed at positioning Yugoslavia differently from Soviet communism on the geopolitical stage. Nevertheless, interventions in the capital often lacked organic planning, and due to the compactness of the Ottoman city, these plans left scattered, incomplete pieces and, in some instances, erased vital parts of the historical fabric.

The most conspicuous legacy is the fragmentation, not only in urban layout but also in language. An example is the National Library (1982) in Pristina, designed by Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjakovic (1929), which stands as a surprising and majestic structure within an urban context that remains something of a large «urban wasteland» (Jacob, 2019). The Library's clear geometric volumes, marked by an external metal structure, lend it a majestic and visible presence from a distance, revealing a human scale within its interior.

Montenegro (Nikolić, Marović) also underwent a transformative process in shaping its national identity and societal dynamics during the era of the «Third Way» within the Cold War context (Stierli and Kulić, 2018). This period witnessed the introduction of "paid holidays for workers" and the promotion of tourism along the coast, leading to the construction of numerous hotels to meet the growing demand. Beginning in the 1960s, the architectural landscape started to feature compositions of multiple forms and increasingly intricate megastructures. These developments aimed to entice travelers to explore the entire coastal region of Yugoslavia as outlined in the Regional Territorial Plan for the Southern Adriatic, later known as "Jadran I." Architect Milan Popović played a pivotal role in shaping a distinctive architectural approach for Montenegrin coast hotels. His designs emphasized the harmonious interaction between architecture and nature, incorporating terraces, promenades, and green spaces adorned with indigenous vegetation. This architectural lexicon became a hallmark embraced by an entire generation of architects.

During this period of cultural resurgence, Skopje (Tornatora, Bajkovski) assumed a central role. Following the catastrophic 1963 earthquake that devastated the capital of North Macedonia, a national and international discourse on the city's reconstruction commenced. The objective was to manifest Yugoslavia's political, economic, and social aspirations, drawing inspiration from the experiences of New Zagreb (1930-1962) and New Belgrade (1929-1954). Indeed, Skopje, akin to Brasilia (1960) and Chandigarh (1953), offered a canvas in the 1960s for embodying the principles of modern architectural culture - a vision both ambitious and marked by contradictions.

Tange's Plan for the revitalization of Skopje presented a unique opportunity to showcase the model of Yugoslav socialism to the world. It transformed the city into an international laboratory for concrete reflection on the urban theories promoted by CIAM. The radical and futuristic vision put forth by the Japanese team, which emerged as the competition winner, embodied the ideals of post-earthquake reconstruction. This innovative approach to city planning drew inspiration from Japan's modernization model. Tange served as a bridge between the traditions of the Eastern world and the modern Western architectural language. His vision had the potential to project Yugoslavia onto the international stage by reestablishing New Skopje through a monumental infrastructural system, a concept previously experimented with in the Tokyo Bay Plan (1960).

The city is meticulously planned with a network of continuous vehicular and pedestrian connections. Within this framework, distinct architectural «new prototypes» (Tange 1965) are strategically integrated, serving as defining elements that underpin the urban design. Notable among these are the City Wall and the City Gate, alongside which a proliferation of exposed concrete structures gives rise to what can be described as a «bèton brut cityscape». (Lozanovska, 2015)

Highlighting the architectural diversity within Yugoslavia, several women architects also played pivotal roles in city planning. Notably, figures such as Milica Šterić (1914-1998), Mimoza Tomić (1929), Olga Papesh (1930-2011), Svetlana Kana Radević (1937-2000), among others, brought a unique perspective to their designs, imbuing them with an "emotional" and "sensitive" quality. Their experiences gained abroad allowed them to infuse a certain fluidity into architectural and urban solutions.

While there's no denying the strong push for unifying Yugoslavia's national identity during the transformation processes of various cities, it often encountered local events, resulting not in a homogeneous and cohesive architecture, but rather a series of adaptations in different "centers."

Amidst this intersection of languages and experiences, the constellation of Spomenik, a Serbo-Croatian term for monument, created between the 1950s and 1990s, serves as a unifying and overarching element that connects the diverse peoples of former Yugoslavia (Amaro, Schepis).

With nearly 14,000 memorials (the number is indefinite due to the lack of a real census), initially erected by Tito to commemorate the victims of the People's Liberation Struggle (1941-1945), scattered throughout the territories, they form a national network transcending differences and etching the imprints of memory onto the landscape. These memorials, spanning from mountainous regions to coastal areas, stand as dynamic features in the landscape, shaping communal spaces that link people, memories, and the narrative of the "New Yugoslavia." This extensive construction of monuments represents a profound testament to the nation's history.

There is no doubt that the comprehensive program of socialist Yugoslavia remains unfinished. The completed projects, still functional, continue to represent the foundational and identity framework of Slavic cities, bearing witness to profound social transformations and the subsequent principles of modernization. This mosaic of projects, marked by interruptions and incompleteness, boasts an exceptional quality and quantity. It bestows upon architecture the crucial role of materializing the intersection between a shared history and collective identity in a multi-ethnic state, characterized by the coexistence of diverse influences. With the collapse of socialism and the disintegration of Yugoslavia, this multitude of works ceased to be perceived as a symbol of modernity but became emblematic of a past to be eradicated through various transformations and demolitions. Although a significant portion of this heritage is still in use today, the original concept of urban development for the greater public good has been all but erased by isolated and disparate interventions. The utopian vision embodied by architecture has succumbed to the divisive forces among different nations. Many public buildings have been privatized, while numerous monuments have suffered acts of vandalism or outright demolition.

Nonetheless, this body of work serves as a poignant reminder of the pressing need for in-depth analysis to address a significant cognitive and historiographical gap. This gap is evident in the scarcity of publications available beyond Slavic languages. Moreover, it compels us to challenge prevailing cultural stereotypes, such as the one posited by Stierli (2018), asserting that «Viewed through the contemporary Western lens, the Balkan region, and more specifically, Yugoslavia, is scarcely considered a hub of cultural and architectural innovation.»

This position is supported by the historian Maria Todorova, who has attempted to demonstrate how, since the mid-19th century, Western culture has established a negative image of the Balkans. This negative perception created a clear distinction between the Balkans and Europe: Europe represented a positive image based on Enlightenment values, while the Balkans were cast in a negative light.

YU_topia. Balkan architecture aims to provoke reflection on several unresolved questions. Can we envision the architecture of Yugoslavia and, more broadly, the Balkans from a different perspective? Could the modernization process of its cities be seen as the «invention of tradition» (Hobsbawm and Ranger, 1997)? Perhaps contemplating this geographical space means expanding research horizons, as suggested by Łukasz Stanek in Architecture in Global Socialism. This could involve exploring encounters between European socialist countries and those in Africa and Asia during the Cold War, when collaborative exchanges had an impact on architecture and urban planning.

In conclusion, it is possible to reframe the Balkans, shedding the perception of isolation and marginality that twentieth-century architecture has imposed upon it. This can be achieved through a lateral perspective capable of inspiring new narratives and geographies. As Franco Cassano has demonstrated, this perspective reflects upon an ever-expanding Europe, burdened by models imposed by Nordic culture.

As the rhetoric of modernity faces its first significant challenges, and contemporary theoretical debates begin to delve into the postmodern era, the Mediterranean transcends its exclusively negative configuration. It starts to evolve in meaning. The image of the Mediterranean undergoes a profound transformation: it is no longer a mere precursor to modernity or a degraded periphery, but rather a reshaped identity to be rediscovered and reinvented in connection with the present. It ceases to be an obstacle and instead becomes a valuable resource (Cassano, 2003).

Notes

[1]

Landscape_inProgress Landscape_inProgress is a research and

design initiative, led by Marina Tornatora and Ottavio Amaro from the

Department of Art. The initiative explores "Landscapes in Progress,"

which are landscapes undergoing transformation, often due to

large-scale projects or significant events that alter, and sometimes

completely redefine, their existing characteristics.

The Laboratory is designed as a multidisciplinary space that connects

architecture, urban environments, and landscapes. It engages various

professionals, including architects, landscape architects, agronomists,

photographers, artists, and more, in the exploration and interpretation

of these spaces.

The primary concept is to explore these territories through a dynamic

perspective, simultaneously approaching and distancing from them. This

approach allows for the recognition and documentation of the values and

imagery within these complex and diverse landscapes. The Laboratory

collaborates with both public institutions and non-profit

organizations, conducting consulting and scientific research

activities. This collaboration ensures an integrated and innovative

approach to the study of cities and landscapes.

[2] "The As Found" concept originated during the Parallel of Life and Art exhibition in 1953 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. This exhibition was curated by A. P. Smithson, E. Paolozzi, and N. Henderson. The collages featured in "As Found" present a unique juxtaposition of images, including archaeological fragments, ethnic masks, human body parts, X-ray scans, and microscope images..

Bibliography

AA.VV. (1961) – Casabella, n. 258.