Socialist Prishtina: The tale of unfinished urbanization

Florina Jerliu

Fig.

1 - Sequence from the former Marshal Tito Street, before and after

demolition of the 16th century Lokaq Mosque and the construction of the

Hotel Bozur (later Hotel Iliria). The modernist hotel

“Iliria” was privatized in 2006 and soon was destructed to

make space for a new hotel Swiss Diamond. (Photo source: Municipality

of Prishtina Photo Archive).

Fig.

2 - Sequence from the modern city center, showing the mode of

unfinished task of socialist urbanization (Photo excerpt from Google

Earth 2022, drawing by the author).

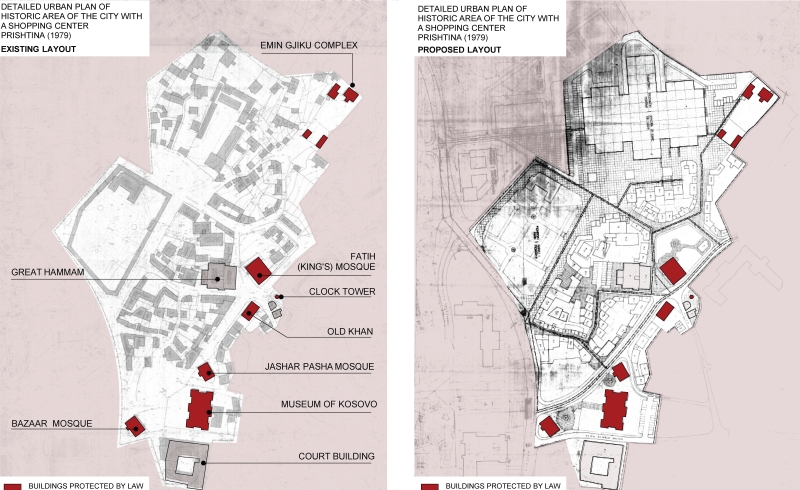

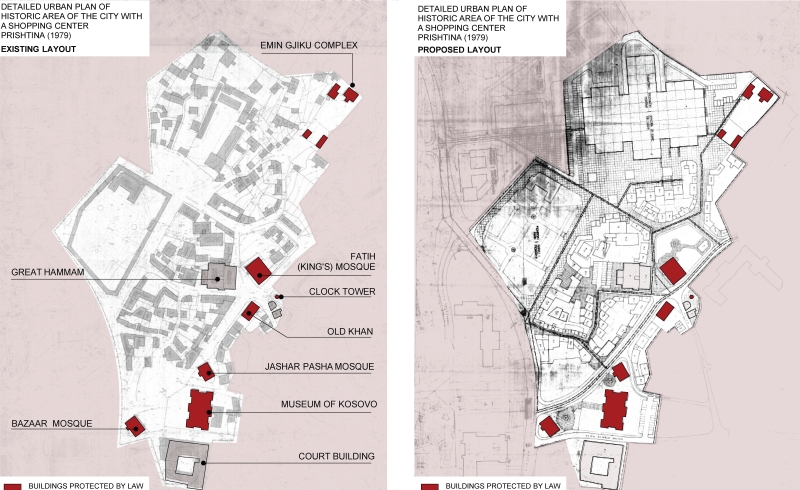

Fig.

3 - DUP for the Historic Core: existing situation (left), proposed

layout (right). [Figure-base: Urbanisticki Zavod Opstine Prishtina,

1979; drawing by author].

Fig.

4a - Modern architecture in Prishtina. a) Ulpiana neighborhood built in

1960s in free land; one, if not the only example of successful planning

implementations. (photo source: facebook community page 'Prishtina e

Vjetër' in: https://web.facebook.com/PrishtinaOLD/ (accessed

7.12.2017).

Fig.

4b - Modern architecture in Prishtina. b) National Library; until late

2004 the surrounding of the library was deserted. Greening and few

paths were introduced latter to enable access from the university

buildings located in the near vicinity. (photo source: facebook

community page 'Prishtina e Vjetër' in:

https://web.facebook.com/PrishtinaOLD/ (accessed 7.12.2017).

Fig.

4c - Modern architecture in Prishtina. c) National Library; until late

2004 the surrounding of the library was deserted. Greening and few

paths were introduced latter to enable access from the university

buildings located in the near vicinity. (photo source: facebook

community page 'Prishtina e Vjetër' in:

https://web.facebook.com/PrishtinaOLD/ (accessed 7.12.2017).

Fig.

5 - Map of Prishtina Urban Plan 2000, 1987.

Introduction

Prishtina, the capital of the Republic of Kosovo, once the center

of the Vilayet of Kosovo (before the fall of the Ottoman Empire), was

the capital of the Province of Kosovo within ex-Yugoslavia. It used to

be a typical Ottoman city, with a compact urban structure and an

identifiable nucleus, the Old Bazaar. Neighborhoods were evenly

distributed around the Bazaar and, as in other Ottoman cities, they

maintained a superb distinction between public and private realms

(Pasic 2004, p.7). Throughout the late 1940s and 1960s, the Bazaar was

razed to the ground by the socialist regime, making way for the new

city center. This symbolic space was chosen to set the scene for the

new Yugoslavian representation of Kosovo, emerging in the form of the

Brotherhood and Unity Square, and two state institutions on either side

of the square: the Municipal Assembly Building and the building of the

Regional People’s Committee for Kosovo (today the Parliament of

Kosovo). The socialist urbanization of Prishtina replicates such

patterns of ideological interventions in the rest of the existing city

structure.

De-Ottomanization of the capital city meant not only becoming

Yugoslav and modern, but also maintaining an inferior identity of

Kosovo Albanians within the federation (Le Normand, p. 258; Malcolm

1998, p. 314). The planned destruction of a large proportion of the

traditional architecture justified on the ground of liquidating the

backwardness of the Ottoman city (Mitrovic1953, pp. 165-166), [1] was based not on genuine urban

plans as commonly witnessed in other ex-Yugoslav cities, but rather on

so-called «urban activities», a term coined by socialist

planners to describe the actions that were «necessary for

preparing a study on the development of Prishtina» (Jovanovic

1965). Throughout the socialist period, studies, plans, and

«urban activities», were carried out simultaneously,

sometimes independently, yet often left incomplete. Thus, fragmented

intervention as an output, and unfinished urbanization as a process,

became the most distinct legacy of city’s modernization.

There is a small body of documentation regarding the urban

development of Prishtina during socialism, although in recent times the

number of publications on the architecture of the period has increased

significantly, [2] along with the

awareness of its preservation. However, the gap of knowledge persists

on the context of state and urban policies that gave shape to the city

development, and this is identified and addressed briefly in this

contribution. I argue that shedding light to the interplay of planning

decisions and activities on the ground, both chronologically and

thematically, helps to understand certain aspects of implementation of

urban policies, which were in line with state policies of the

ex-Yugoslavia, while complementary to the specific policy of Serbia in

Kosovo. Therefore, this study mainly relies on and analyzes the

official and archival documents of the period, with the belief that

they are rather overlooked by the scholars, while in fact they comprise

an important source on the context and contents of planning. In this

regard, few relevant quotes are brought in full, which in hand

illustrate the official language and overall ethos of the time, and

fill-in the larger picture of the mode of urbanization in socialist

Prishtina.

Laying the Foundations of the New Socialist City

In the aftermath of the Second World War, among major undertakings

in ex-Yugoslavia was to lay the foundations for new modern socialist

cities, and this was made clear through various official documents and

statements, as illustrated in the quote below:

[...] Prishtina abandoned its former characteristics, and has

grown, and is growing into a modern city; its physiognomy is

fundamentally changing, it is transforming with an unprecedented rhythm

and is erasing all what identified it with a remote

‘kasaba’ [town] (Zikic 1959, p.24) [...] it is leaving its

past behind and is becoming a modern city – a new socialist

city’ (Cukic e Mekuli 1965, p.12).

This journey in Prishtina commenced in 1947, marked by the

transformation of the primary south-north artery (previously known as

Lokaq street) into a modernist boulevard, purposed to accommodate newly

established state institutions; and was renamed into Marshal Tito

Street. The initial modern structure to rise along its eastern front

was the Provincial Committee (today the Ministry of Culture),

sequentially accompanied by other institutions, such as the National

Theatre, the National Bank, and the Municipality of Prishtina, among

others (Jovanovic, B. 1965). By 1953, the street transformation came

almost to its end.

The Marshal Tito Street project required massive demolitions; beside

the Old Bazaar, formerly located at the northern end of the axis, a

large portion of traditional architecture including historic buildings

(a catholic church and a mosque), were razed to the ground (Jerliu, F

and Navakazi, V. 2018) (Fig. 1). It is noteworthy to highlight that

this transformation occurred well prior to the adoption of the Detailed

Urban Plan (DUP) for the city center in 1967 (Pecanin).

The «retroactive planning» of the city center, as

understood from the quote below, was implemented to alleviate the

challenge of finishing the planned urban blocks. They were partially

developed to house new institutions, but private parcels within the

envisioned enclosed urban block typology, were left untreated. Even

today, they are spaces filled with private houses: a pre-socialist

cadaster awaiting to be regularized (Fig.2).

This plan was partially implemented for the needs of the

administration of the Province, the Municipality and other public

facilities... The realization of these spaces destroyed the old Bazaar

and a large number of facilities in the surrounding environment. Other

contents cannot be realized due to the existing housing, and this plan

should be put out of force. (ibid)

In a way, the plan was designed with the expectation of being phased

out, which reveals the overarching intention of the socialist regime:

to construct the facade of the Marshall Tito Street rather than to

urbanize the city center to the benefit of residents, being in majority

Albanians (Jerliu and Navakazi 2018).

Socialist Urban Planning: “Loading…”

A milestone date in the city development is 1953. This is the year

identified among other as the beginnings of a large-scale deportation

of Kosovo Albanians, as part of the treaty signed between ex-Yugoslavia

and Turkey. The so-called «Gentleman's Agreement» reached

in January 1953 between Tito and the Turkish foreign Minister Khiprili

requested that Yugoslavia fulfils the 1938 Convention, according to

which about one million inhabitants were to be settled in vacant

regions of Turkey. Between 1945 and 1966, known as the

«Rankovic’s Era»[3],

roughly 246,000 were deported to Turkey from the whole ex-Yugoslavia of

which 100,000 people (mainly Albanians) from Kosovo alone (Malcolm

1998, p. 323).

This process had a profound impact on Prishtina, both

demographically and economically: most of the investments during this

period were concentrated in the capital-investment, rather than

labor-investment. Also, investments were made in primary industry such

as in mines, power stations, and basic chemical works, a sector that

was intended to supply Kosovo’s raw materials and energy for use

elsewhere in Yugoslavia. (Malcolm 1998, pp. 322-324).

The year 1953 is also symbolic for the beginnings of urban plans in

Prishtina. It is the year of adoption of the Urban General Plan

for Prishtina 1950-1980, drafted by Iskra from Belgrade

under the leadership of Dragutin Partonjic. The plan foresaw the city

growth from 24,081[4] to 50.000

inhabitants and surface from 223.04 Ha to 950 Ha. While information on

the technicalities of the plan is briefly revealed in a later Prishtina

Urban Plan 2000 (PUP 2000), a report from 1953 Gradovi i

Naselja… provides the substance of the plan. Given that the

language used in this report is rather self-explanatory, hence the

quoted vision:

The geopolitical position of the city, its role in the economy of

the country (ex-Yugoslavia], especially of its wider region, the

changes in social conditions, the relatively rich economic hinterland,

the inherited primitive and materially poor construction of heritage,

and other factors, impose the need, in solving the urbanization

problems of Prishtina, for a general reconstruction of the existing

situation, not only of the city but also its immediate surroundings.

Based on the analysis of established current and possible objective

conditions, the future development program for the next 20 years

envisions Prishtina with an increased population of 50,000 and an

economic character as a poorly developed industrial city, with

predominantly processing industries employing 8-10% of the population.

The guidelines of the program had to inevitably reflect in the basic

framework of the regulatory plan. The applied type of urban

reconstruction anticipates the acquisition of free territories and

radical measures for the rearrangement of the built-up area, with

maximum utilization of inherited values. (Mitrovic 1953, p. 166)

Based on this rather unambitious vision, the new city borders were

set. Extensive reconstructions took place in the inner-city while

vastly disregarding its built heritage, and the southern outskirts

developed into new modernist neighborhoods. However, within a decade,

the city's population had reached the envisioned figure of 50,000

inhabitants,[5] therefore, a

decision was made to expand the

city boundaries from 950 hectares as planned in 1953, to 1950 hectares

(Cukic and Mekuli 1965, p.36). Interestingly, PUP 2000 disclosed that

no material evidence on urban plans for the following development phase

were found in the premises of the Municipality of Prishtina:

Judging by the note that this space was planned for 107 954

inhabitants until 1980, this could have been the amended Prishtina

Urban Plan [alluding to Partonjic 1953 Plan], for which no traces of

documentation exist. [So] In 1965 arch. Nikola Dobrovic began the

drafting of the “Directive Plan for Traffic and Land Use for the

city”, which was completed and approved in 1967. The plan was

drafted for 100,000 inhabitants and surface of 1950.00 hectares. From

documentation, only the graphic annex of land use exists (S: 2500). In

1969 the decision was made that the “Directive Plan for Traffic

and Land Use for the city” is replaced by the General Urban Plan

for Prishtina, by which the Plan of 1953 ceased to be in force.

(Municipality of Prishtina 1987, p.11)

As the quote reveals, throughout 1960s-1970s, there was a process of

planning for a new “general” plan. In meantime, as of 1965,

and well beyond until mid-1980s, urban development in Prishtina

continued its pace on the basis of smaller plans, namely, Detail Urban

Plans (DUPs), which according to the planning officials:

«… [were] based on the Decision that replaces the General

Urban Plan from 1966, and more recently on the General Plan of

Prishtina» (Pecanin). Regardless the confusions

deriving from this statement as to which plan substitutes or is

substituted by a certain decision or plan, or whether generally existed

any General Urban plan, DUPs were made for various sizes of space and

contents, ranging from large-scale neighborhoods to small housing

areas, be it built-up areas scheduled for demolition or free land, from

large to small complexes of housing and public buildings; there were

even DUPs for individual buildings too[6].

According to

archival data, between 1967 and 1986 a total of 34 DUPs were drafted;

by 1990, majority of DUPs were partially implemented and only a small

number of them were in fact fully realized (Pecanin).

Another victim of «retroactive planning» was the

Historic Core. The Detailed Urban Plan (DUP) for the Historic Core was

approved in 1979, which is over 30 years after systematic and planned

destruction of Prishtina’s urban built heritage. Although in

principle DUP should have intended to protect the survived heritage,

its highlight was the planning for a massive commercial building of

18,600 sqm, occupying circa 60% of the total planned newly built area.

This superstructure foresaw to amalgamate the shops which started anew

eastward Bazar’s area after its destruction: the Bazar's second

life was beginning, and the regime went after this one too. Spatial

analysis reveals that the plan aimed to preserve roughly 50% of the

existing area, of which 8.6% was roadway, 24.6% green space, and a mere

11.7% existing structures, which included a handful of significant

monuments. The remaining half of the area was earmarked for

reconstruction. (Urbanisticki Zavod Opstine Prishtina, 1979, pp.20-22)

(Fig. 3).

Since its inception, the DUP for the Historic Core was continuously

opposed. In 1987, PUP 2000 introduced new boundaries and conditions for

the preservation of historic area, and by 1990, authorities had also

acknowledged their complete failure in safeguarding city's

pre-socialist past (Pecanin.).

The Promise of Urbanization

During mid-1970s and 1980s, Prishtina benefited the most from the

Yugoslav development fund for underdeveloped regions. (International

Monetary Fund, 1985). A considerable portion of this fund in the urban

development sector was allocated for planning, and to a lesser degree,

for building new state institutions, one of which was the University of

Prishtina, established between 1975 and 1977. The University acted as a

catalyst for large-scale internal migrations to the capital, resulting

in its rapid expansion: between 1971 and 1981, the population

nearly doubled, increasing from 69.514 inhabitants in 1971 to

108.083 inhabitants in 1981. (Municipality of Prishtina 1987, p.5)

During this periuod, Prishtina witnessed substantial growth in its

southwestern area, characterized by the creation of new modernist

neighborhoods, yet, with no foresight for their physical

interconnection. This included the creation of Dardania, Sunny Hill 1,

Sunny Hill 2, and Lakrishte neighborhoods, while Ulpiana neighborhood

had already been built in the late 1960s (Fig. 4.a). Significant

segments of the city's outskirts were also planned through DUPs,

primarily for individual housing, like the Tauk Basce small

neighborhood, Aktash 3, Dragodan hill, among others (Pecanin.). As was

common in other socialist cities, these houses were constructed for the

wealthy and higher-income working-class groups (Szelenyi 1983, p. 63).

Contrastingly, the remainder of the city, particularly its entire

north, was largely overlooked throughout the entire socialist era.

The most significant architectural contribution of this period was

the construction of modernist public buildings. However, similar to the

case of new modern neighborhoods, they often lack integration with

their surroundings, thus creating disjointed spaces. Many public

buildings, like the National Library for instance, failed to shape

cohesive urban quarters due to the unfinished public space in front and

around them (Fig. 4.b). The reasoning behind such an approach might

have been political, as the social utilization of urban space,

especially public gatherings, were perceived as a potential catalyst

for Kosovo Albanians' revolts against the former socialist regime.

The promise for comprehensive urbanization of Prishtina was most

convincingly given by the 'Prishtina Urban Plan 2000' (PUP 2000),

approved in 1987 (Fig.5). This plan, the final one conceived during the

socialist era, remains one of the few official documents that still

serves as a valuable resource in understanding the city's narrative.

PUP 2000 sought to rectify the accumulated spatial and social

discrepancies and challenges. It conceded that Prishtina's development

suffered from a lack of consistent and inclusive planning, which, as it

postulates, led to the formation of three markedly different spatial

entities in the city, each unique in its creation and development: 1)

The neglected and unplanned northern part of the city, typified by poor

living conditions, thus urgently needing improvements; 2) The historic

city center inclusive of new modern buildings, necessitating the

completion of the residential urban infrastructure, with a specific

emphasis on rehabilitating the historic core; and 3) The new modernist

center and southern parts of the city, which began developing from the

1960s onwards, characterized by solid construction and services, but

requiring phased reconstructions and completion (Municipality of

Prishtina 1987, pp. 38-39, 57-59). This categorization endures even

today, attesting to the substantial impact of fragmented and unfinished

process of urbanization of the city.

PUP 2000 also noted that:

[...] the protection and regulation of archaeological sites and

historic nucleus is imperative, since the future of this sector risks

to be left without its past, and the results of creation of

contemporary values risk the abruption of historical and cultural

continuity. (Municipality of Prishtina 1987, p. 172)

Two years later, with the ascension of Milosevic to power in

ex-Yugoslavia, Kosovo entered a terrible phase of state repression that

greatly undermined the comprehensive urbanization improvements as

proposed by PUP 2000. In the present day, Prishtina has developed new

urban plans; however, PUP 2000 - more often being overlooked than

revisited -continues to be vital in genuinely tackling the city’s

challenges rooted in its socialist past.

Conclusion

The tale of socialist Prishtina is one of unfinished

urbanization. Its modernization during the socialist era is intriguing

- especially if juxtaposed with other centers of ex-Yugoslavia - not

only for understanding the nuances of modernist and socialist urban

policies, but also to make sense of what has been inherited from that

era and how it has influenced the city's subsequent development.

Enlightening in this view are the official documents and statements of

the time of socialism; their analyses offer significant insight into

the enduring impact of the political ideology in city's intricate urban

development.

Initially, the Ottoman city had a compact urban structure; it was

deranged in the name of recreating it as a compact modern city, but

this aim was not truly achieved. Instead, the rebuilding process erased

vital fragments of historical tissue, while new development themselves

were left scattered throughout the urban landscape. As a result, the

once compact city became fragmented. Thus, fragmentation is the legacy

inherited from the socialist era, and comprehending its content, along

with the latent potential for its recalibration in line with the

premise of historical continuity, as advocated in current discourse,

proffers a hopeful alternative for the present and future of the city's

modernist legacy, as well as a means of overcoming its "unfinished"

condition.

Notes

[1] The 1953 report on cities

and towns in Serbia defined the existing architecture of the city of

Prishtina as to being remote, and therefore, subject to the so-called

«general radical reconstruction» of the «primitive

appearance and poverty of material and architectural heritage values of

the city»

[2] Some recently published

books on Prishtina are: A; Sylejmani, Sh. (2010). Prishtina ime (My

Prishtina). Java Multimedia production: Prishtina; Hoxha, E. (2012)

Qyteti dhe Dashuria: Ditar Urban - City and Love: Urban Diary, Center

for Humanistic Studies “Gani Bobi” Prishtina; Gjinolli I,

Kabashi, L., Eds. (2015). Kosovo modern: an architectural primer,

National Gallery of Kosovo, Arbër Sadiki (2020) Arkitektura e

Ndërtesave Publike në Prishtinë (Architecture of Public

Buildings in Prishtina), NTG Blendi, Prishtinë, among other.

[3] Aleksandar Rankovic, the

Minister of Interior who was known for directing a harshly

anti-Albanian security policy, was dismissed in 1966.

[4] 24, 081 inhabitants

reflects the figure from the second registration of population carried

out in the same year, 1953, by the socialist regime in ex-Yugoslavia.

[5] This growth is mainly

attributed to the natural growth of the Albanian population in Kosovo,

a feature that characterizes the demography of Kosovo throughout the

20th century. For more information on population growth during the 20th

century see: Statistical Office of Kosovo (2008), Table 2, p.7.

[6] The strategy of

‘fragmented' development through DUPs was observed in

ex-Yugoslavia during the 1960s, as a result of inconsistent execution

of urban plans after the Law on Urban and Regional Planning was enacted

in 1961. (See: Le Normand 2014, p.118.) However, in Prishtina this mode

of development continued throughout the socialist period.

Bibliography

CUKIC D. and MEKULI E. (1965) – The Prishtina Monograph,

Municipality of Prishtina, Prishtina.

Facebook community page Prishtina Ime in:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/620037062517530/ [Last accessed July

2023].

International Monetary Fund (1985) – Yugoslavia and the

World

Bank, available online in:

<https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/295801468305930648/pdf/777760WP0Box370lavia0and0world0bank.pdf>

(Last accessed July 2023)

JERLIU F. e NAVAKAZI V. (2018) – “The Socialist

Modernization of

Prishtina-Interrogating Types of Urban and Architectural Contributions

to the City”. In: Mesto a Dejiny [The City and History]. Vol. 7

(2),

pp. 55-74

JOVANOVIC B. (2011) – “Urbane aktivnosti u

Pristini” Izvestaj, Jun

1965. Urban activities in Prishtina, report, June 1965, retrieved from

the Prishtina Municipality Archive in May.

LE NORMAND B (2014) – Designing Tito’s Capital:

Urban Planning,

Modernism, and Socialism, University of Pittsburgh Press,

Pittsburgh.

MALCOLM N. (1998) – Kosovo. A short History,

Macmillian

Publishers, New York.

MITROVIC M. (1953) – Gradovi i Naselja u Srbiji.

Urbanistički Zavod Narodne Republike Srbije, Beograd.

Municipality of Prishtina (1987) – Prishtina Urban Plan

2000

(PUP 2000), Prishtina.

PASIC A. (2004) – “A Short History of Mostar”. In:

Conservation

and Revitalisation of Historic Mostar, The Aga Khan Trust for

Culture, Geneva

PECANIN S. – Spisak Detaljnih Planova na Teritoriji Grada

Pristine, List of Detailed Plans in the Territory of the City of

Pristina. Archival document, undated. [Retrieved from the Prishtina

Municipality Archive in May 2011].

SZELENYI I. (1983) – Urban Inequalities under State

Socialism,

Oxford, University Press

<https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ewZYRfsWz_4HvtIgsUQ5Ws_3NXX__Sm4/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=105977315545044376017&rtpof=true&sd=true>

Statistical Office of Kosovo (2008) – Series 4: Population

Statistics. Demographic changes of the Kosovo population 1948-2006.

Available online:

<https://ask.rks-gov.net/media/1835/demographic-changes-of-the-kosovo-population-1948-2006.pdf>

[Last accessed July 2023].

Urbanisticki Zavod Opstine Prishtina (1979) – Detaljni

Urbanisticki Plan Istorijske Zone Grada sa Zanatskim Centrom

(Urban Plan of the Historical Zone of the City with the Craft Center of

Prishtina) Prishtina.

ZIKIC R. (1959) – The Prishtina Monograph, Prishtina.