Skopje: concrete vs fiction. From Internationalism towards

ethnonationalism

Marina Tornatora, Blagoja Bajkovski

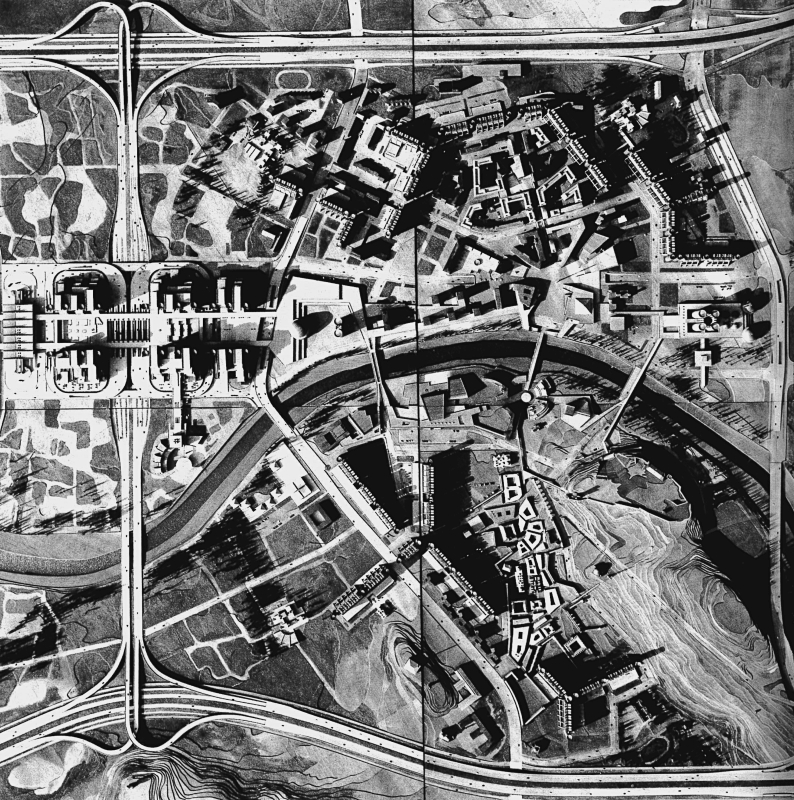

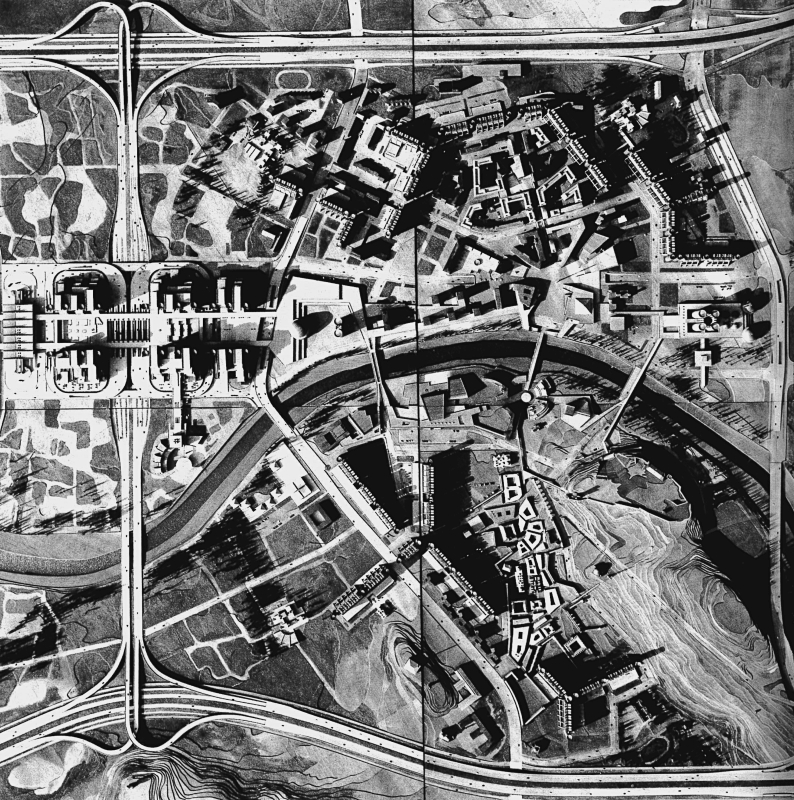

Fig.

1 - Kenzo Tange, Model of the Master plan for New Skopje, 1965.

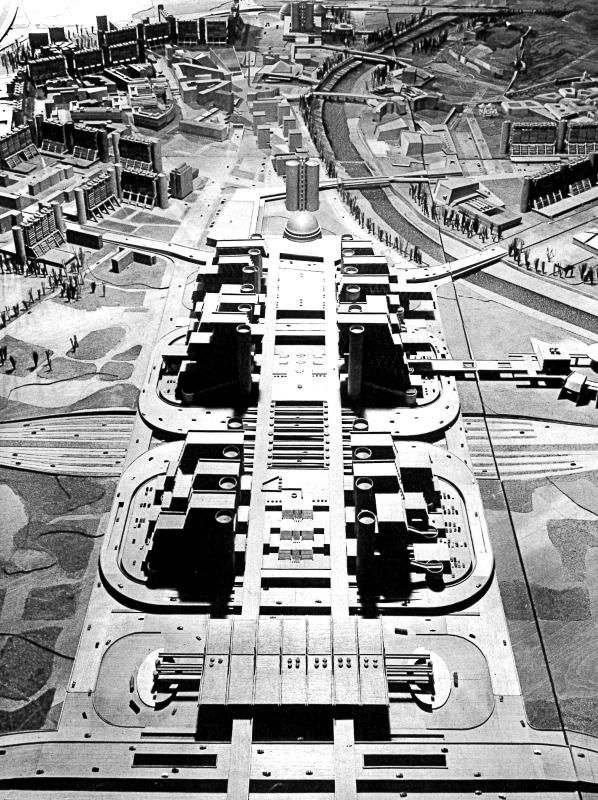

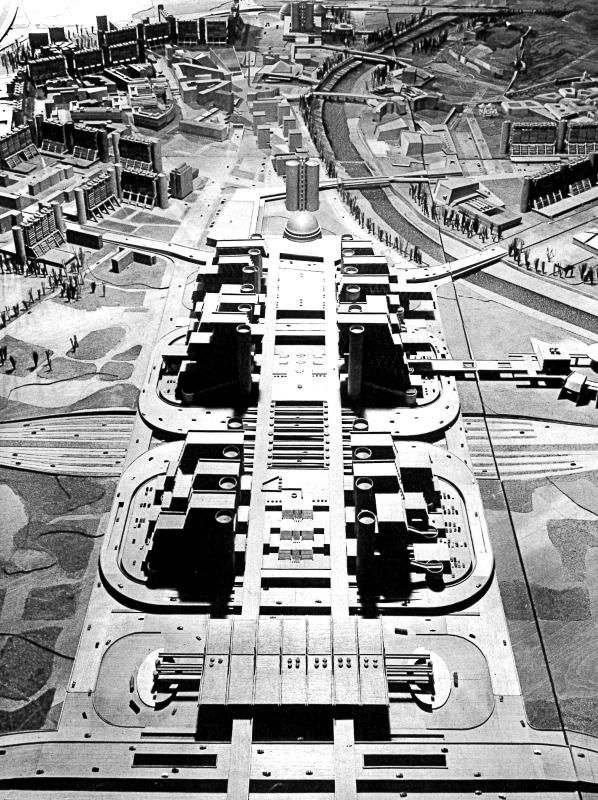

Fig.

2 - Kenzo Tange, Model of the Master plan for New Skopje, 1965. View of

the City Gate.

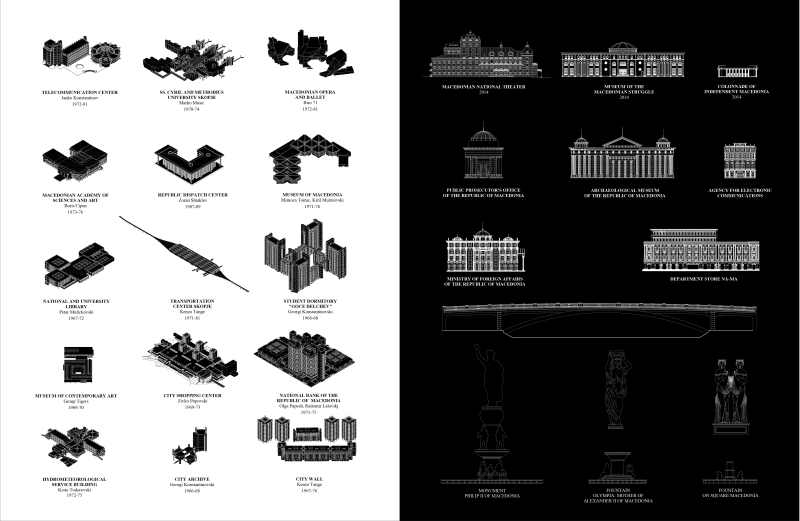

Fig.

3 - Kenzo Tange, Transportation Center (1971-1981).

Fig.

4 - Janko Konstantinov, Telecommunications Center (1972-1981).

Fig.

5 - Zivko Popovski, Commercial Center (1967-1972).

Fig.

6 - Mimoza Tomić and Kiril Muratovski, Museum of Macedonia (1971-1976).

Fig.

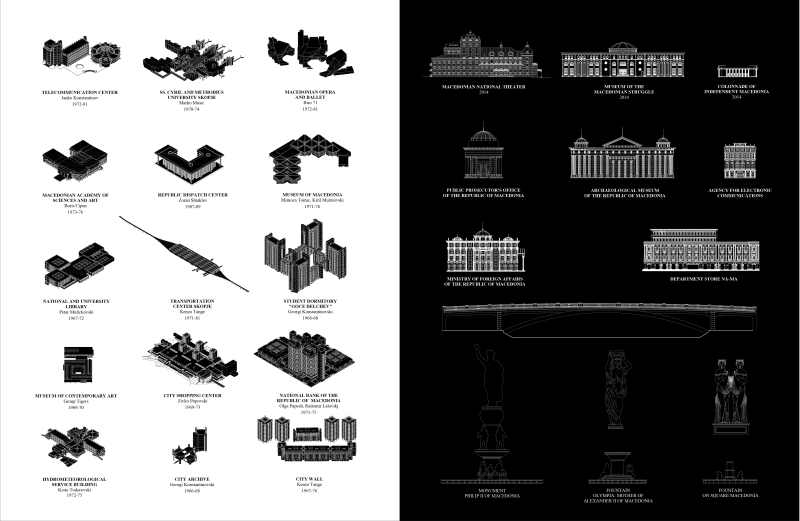

7 - Comparison map between post-earthquake architectures (in white) of

Kenzo Tange's plan and interventions of the SK2014 plan (in red).

[in

white, Skopje Brutalism]

1. Telecommunications Center,

2. Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts,

3. National and University Library,

4. Macedonian Opera and Ballet,

5. Museum of Macedonia,

6. National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia,

7. Saints Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje,

8. Republic Dispatch Center,

9. Skopje Transport Center,

10. Museum of Contemporary Art,

11. City Walls,

12.City Shopping Center.

[in red, Skopje 2014]

1. Macedonian National Theater,

2. Museum of the Macedonian Struggle,

3. Archaeological Museum,

4. Marriott Courtyard Hotel,

5. Marriott Hotel,

6. Ministry of Finance,

7. Agency for Electronic Communications,

8. Public Prosecutor's Office,

9. Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

10. Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services,

11. Commission for the Regulation of Energy and Water Services,

12. MES Macedonia (Energy Regulatory Commission of North Macedonia),

13. Ministry of Political System and Intercommunity Relations,

14. Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning,

15. A1 Macedonia Headquarters,

16. Government Building with an eclectic façade,

17. Republic Dispatch Center with an eclectic façade,

18. EVN (Electricity Distribution Company) with an eclectic

façade,

19. Basic Criminal Court of Skopje,

20. Court Palace Garage,

21. Officers' Residences,

22. Gate Macedonia,

23. Monument of Philip II and Alexander the Great,

24. Olympia Fountain - Mother of Alexander the Great.

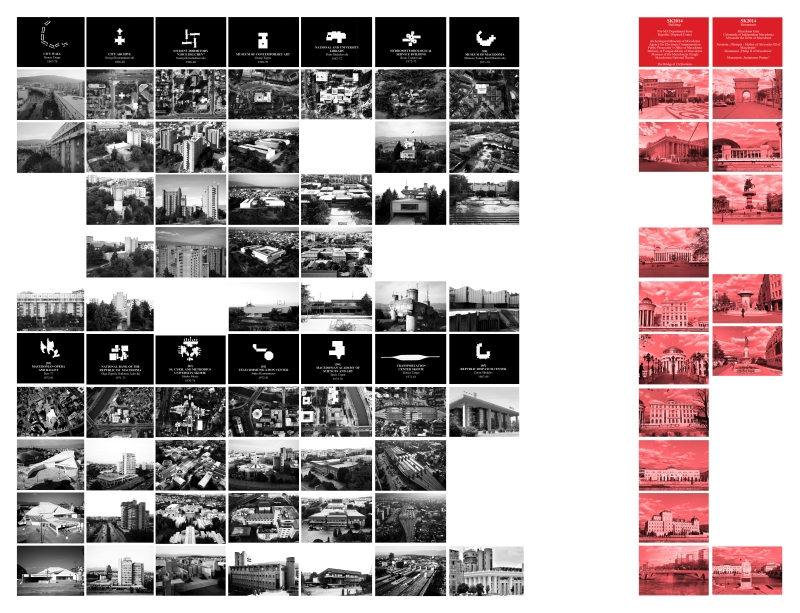

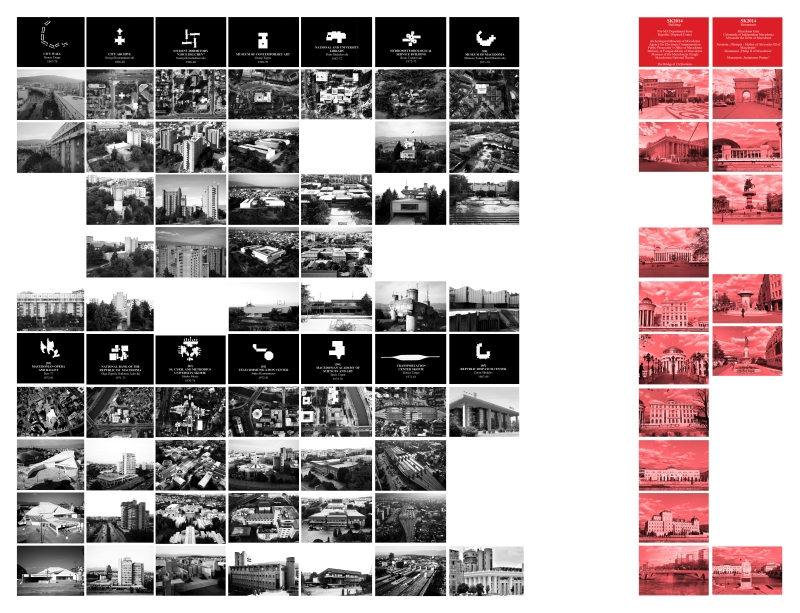

Fig.

7 - Comparison map between post-earthquake architectures (in white) of

Kenzo Tange's plan and interventions of the SK2014 plan (in red).

Fig.

8 - Centro Spedizioni MEPSO (1987-89), confronto tra il progetto

originario e la successiva trasformazione.

Fig.

9 - Macedonian Opera and Ballet (1972-1981), confronto con la

successiva trasformazione dell'affaccio sul lungo fiume Vardar.

Fig.

10 - Campus Universitario Ss. Cyril and Methodius (1970-74), confronto

del progetto originario con il successivo inserimento di nuovi edifici

nel campus.

Fig.

11 - Confronto tra le architetture realizzate dopo il terremoto (1965-

1981) e i recenti interventi introdotti dal Piano SK2014 nel centro di

Skopje.

Fig.

12 - Confronto tra le architetture realizzate dopo il terremoto (1965-

1981) e i recenti interventi introdotti dal Piano SK2014 nel centro di

Skopje.

The prolific architectural production in Yugoslavia after the Second

World War remains a relatively lesser-known chapter in the history of

architecture. Only recently has it been reevaluated, shedding light on

the quality and distinctiveness of a modernization process in which

architecture served as the tangible expression of a societal vision.

This era witnessed highly experimental architectural endeavors on

various fronts, encompassing spatial organization, urban integration,

material utilization, and technical coherence. Moreover, these

experiments incorporated a fusion of urban and architectural decisions

with interpretations of distinct national styles that shaped Yugoslavia.

Within the Balkan region, the city of Skopje (Скопје), the capital

of North Macedonia, stands out as a distinctive case study. With its

current population of 526,500 inhabitants, Skopje holds a significant

place not only due to historical events but also because of the

architectural density that redefined its layout and urban structure

during the 1960s and 1970s.

Skopje can be described as an "interrupted" city, where its visage

bears the marks of numerous transformations and reconfigurations. Here,

the influences of East and West converge and interact, while diverse

ethnic groups coexist, including Macedonians, Albanians, Serbs, Turks,

Bosnians and many others. In the 1960s, Skopje represented an

opportunity to actualize the tenets of modern architectural culture,

akin to more renowned examples like Brasilia (1960) and Chandigarh

(1953).

Tracing its origins back to Scupi, an Illyrian settlement

later annexed by the Roman Empire, Skopje has a history marked by

successive waves of conquests, including Ottoman Turks, Bulgarians, and

periods of Serbian and Yugoslavian control. The city became the capital

of the independent state of North Macedonia in 1991.

Six decades ago, on the 26th of July 1963, Skopje endured a

devastating earthquake registering a magnitude of 6.1. This seismic

catastrophe resulted in a tragic toll, with over 1,000 casualties. The

earthquake wreaked havoc, causing damage to 60% of the existing urban

structures and leaving 80% of homes either severely damaged or

completely destroyed.

In the aftermath of this catastrophic event, the strategic

communication and rhetoric surrounding it, bolstered by the charismatic

leadership of Josip Broz Tito, drew international attention. The

charismatic appeal of Tito led to a massive outpouring of humanitarian

aid, effectively designating Skopje as a symbol of global cooperation

between nations. During the delicate era of the Cold War, Macedonia was

transformed into a sanctuary of peace, where even in the midst of

geopolitical tensions, humanitarian efforts converged. Notably, the

American military, dispatched by President Kennedy, and Soviet

seismology experts, sent by Premier Khrushchev, converged on the same

ground to offer their assistance.

In this context, the Skopje Reconstruction Plan emerged as an

unparalleled opportunity to showcase to the world the Yugoslav

socialist model in action. It transformed Skopje into an international

laboratory for profound contemplation on urban theories that had been

the subject of intense debate within the CIAM (Congrès

Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne). Additionally, it provided a

platform for a generation of Yugoslav architects to actively

participate in the global architectural discourse.

The significance attributed to the reconstruction efforts is

underscored by the involvement of the United Nations. The organization

sponsored and coordinated the international competition for the New

Skopje Plan[1] (1965), under the

guidance of architect Ernst Weissmann (1913-2005), who was the director

of the United Nations Center for Housing, Building, and Planning and a

student of Le Corbusier.

The earthquake, therefore, marked a moment of crisis and upheaval,

but it also presented an opportunity for the reestablishment of Skopje

as a «world city, symbolizing international solidarity and

embracing cosmopolitan ideals, as eloquently articulated by

Weissmann» (Tolić, 2012). The Plan for New Skopje carried

significant symbolic weight, as it aimed to demonstrate «the

physical and technical organization of a specific political, social,

economic, and cultural model» (ibid).

With the belief that solutions could be amalgamated and refined, the

winning proposals emerged from two distinct groups: one led by Kenzo

Tange, accompanied by Arata Isozaki, Yoshio Taniguchi, and Sadao

Watanabe, and the other by the Institute for Urban Planning of Zagreb,

under the leadership of Radovan Miscevic and Fedor Wenzler.

The objective of this article is to delve into the urban model

introduced by Kenzo Tange's Plan (Fig. 1), which has profoundly shaped

Skopje since its reconstruction. Furthermore, it explores the latest

urban transformations the city has undergone, particularly "Skopje 2014

Plan" in relation to Tange’s Plan.

Kenzo Tange's New Skopje

The Japanese team's Plan for the city of Skopje is conceived as an

architectural experiment to be carried out in 40 years, with the year

of conclusion in 2000, designed by a monumental infrastructural system

that organizes and structures the city, as already experimented in the

Plan for Tokyo Bay (1960) and that of the Residential Unit (1959) for

25,000 people, developed at MIT in Boston. In these projects the city

is designed by a network of continuous connections, for vehicles and

pedestrians, to which perfectly recognizable «new architectural

prototypes» (Tange, 1965) differentiated by intended use are

grafted.

The detail with which the architecture is designed opens up a

specific scalar dimension of the city project, in which the macro scale

combines with that of the architectural object. An approach evident in

other projects by Tange, such as the one for the Tokyo Olympics (1964),

the complex in Hiroshima (1949-1959), the Offices in Kanagawa (1958)

and the masterplan for the Osaka International Exposition (1970) in

which

the functional typologies all have their own very specific

volumetric peculiarity which often makes them act in contrast in the

composition, and which makes them become a real experimental laboratory

and source of linguistic inspiration for the Japanese architect's

subsequent projects (Aymonino 2017)

The references to the Cluster City (1952-1953) by Alison and Peter

Smithson also emerge in filigree, in the uninterrupted and branched

cluster system of building bodies. In Skopje, the Japanese architect

starts from tabula rasa, from a zero floor obtained by demolishing

the few pre-existing structures that survived the earthquake, in

correspondence with which he inserts green areas, and identifying a

park on the Kale hill on which the Museum of Contemporary Art stands

today and the Freedom Monument.

The structuring elements of the project are identified in the City

Gate and the City Wall: the "door" and the "wall",

architectural and urban interventions that evoke the memory of medieval

Balkan cities.

By using the concept of the 'door', we not only aimed to model a

structure with the physical appearance of a door, but also anchored in

people's consciousness the idea that it is a door through which one

enters Skopje. If the intervention does not keep its symbolic name, it

will be rejected by the population. The city wall also became famous

and although some argued that the 'wall' was an obstacle and should be

removed, people resisted the idea of a project without it. The city

wall, which became the center of its iconic image, suggested not

abandoning the idea of the 'wall'. We learned, through experience, that

it was necessary to identify a series of symbolic processes in the

project. (Tange, 1976)

Therefore, connecting the radical nature of the project with the

historical identity of Skopje, the "door" and the "wall" that structure

the new urban layout are identified as symbolic elements, becoming the

emblematic signs connected to the local context.

As in previous experiences, Tange reiterates the need to conceive

"new prototypes", through a project that from a territorial and urban

scale proposes architectural solutions investigated through detailed

drawings and large models.

Furthermore, to create that «open structure» with

«infinite growth» theorized in previous projects, the

Japanese team proposes the rotation of the urban system in an East-West

direction, orthogonal to the historical axis, thus defining a decumanus

as a new hallway.

This strategy allows for greater connection with the surrounding

area, the possibility of growth of the city and the dislocation of the

old train station from the central area within in the new urban gate.

Here the City Gate (fig.2), an imposing tertiary and

infrastructural hub, with clear references to the Tokyo Plan, builds a

new raised ground, separating pedestrian connections from car and rail

mobility. An architectural megastructure conceived as an intermodal

«transformer», which should have housed shops, offices,

hotels, cinemas, meeting rooms, only partially built and immediately

judged to be oversized for a reality like that of Skopje.

The decumanus is conceived as an administrative and

commercial axis with a continuous and modular system of vertical

nuclei, where the systems and stair blocks are located, connected by

horizontally suspended corridors which clearly echo the metabolist

architecture of Kisho Kurokawa but also the «street in the

air» by the Smithsons.

Pairs of stairways delineate the pedestrian pathways leading from Gateway

Square to the office block and the car park. The conceptualization

of this urban gateway rested on two paramount objectives: first, to

craft a unified system harmonizing horizontal and vertical movement

trajectories, and second, to conceive a spatial articulation that

exercises visual control over flow, movement, and human perception.

Simultaneously, each distinct space within this complex corresponds to

a physical entity, serving a unique function and adopting a specific

form within the perpendicular alignments, where administrative and

directional activities are concentrated, as well as in parallel to the

axis. Adhering to the visionary planning approach, Tange amalgamates

these dual dimensions on a spatial plane through the inclusion of

pedestrian bridges and stairways enveloping the entrance buildings and

seamlessly intertwining with the office structures. In cases where

buildings connect closely, elevated corridors facilitate the organic

expansion of these spaces on an urban scale. The entire project adheres

to a module that governs the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the

volumes, extending down to the minutest details, thereby establishing a

common language that streamlines communication between designers and

builders. The extensive application of three-dimensional grids

facilitates the creation of intricate spatial configurations grounded

in the concept of a unified scale.

Within the broader City Gate project, only the Transportation

Center (1971-1981) (Fig.3) came to fruition. This remarkable

structure, realized through the collaborative efforts of Kenzo Tange's

studio in Japan, forms the ultimate node of the new East-West axis,

extending toward the regional territory.

The third developmental phase of the Plan is characterized by the

construction of the City Wall, which appears to draw

inspiration from Dubrovnik's city wall. This architectural element

takes the form of a double linear residential strip, resembling a

horseshoe, and serves as the delineation of the new urban center's

perimeter. Its purpose is to accommodate the anticipated population

growth of the city in the future.

The City Wall symbolizes an endeavor to harmonize the deep-rooted

community spirit of the Macedonian people with the requisites of modern

collective living. Recognizing this distinctive aspect, the planning

team conceives a spatial arrangement that preserves neighborly

relations as an inherent quality of the Skopje community. The original

competition project, which initially envisioned residential complexes

with ground-floor shops, underwent modifications during the third

phase. It transitioned into groups of integrated apartments,

incorporating common services within the interstitial spaces.

The architectural composition of the wall comprises two distinct

building typologies. The first consists of a linear terraced structure,

standing 24 meters tall, featuring apartments designed to align with

the height of existing urban buildings. On the upper floors, balconies

extend toward internal courtyards. The second typology encompasses

residential tower complexes, organized in groups of two or three

buildings. These towers are strategically positioned on corners or

along streets, evoking the imagery of a fortified enclosure, akin to

sentinels guarding both sides of the street. In both typologies, the

ground floor accommodates shops catering to daily needs, small

restaurants, bars, offices, and meeting rooms. Additionally, provisions

are made for self-service parking, catering to residents' vehicles.

This eliminates the need for driveways within the courtyards and

introduces a tree-lined strip along the external side, seamlessly

integrated with the primary urban green space, which also houses the

primary schools.

Every meticulous detail and architectural element in Tange's

comprehensive project aims to translate the dynamics of contemporary

society into a tangible spatial arrangement.

Skopje's Béton Brut Cityscape

While Kenzo Tange's renown played a pivotal role in drawing

international attention to the Plan for New Skopje, thus

projecting Yugoslavia's modernization under Tito onto the global stage,

it was during this subsequent phase that the energies of local

architects and artists came to the fore.

Only in recent times, the significance of their contributions has

been adequately recognized. Notable figures such as Bogdan Bogdanović,

Juraj Neidhardt, Svetlana Kana Radević, Edvard Ravnikar, Vjenceslav

Richter, Milica Šterić, Mimoza Nestorova-Tomić, Georgi

Konstantinovskij, and Janko Konstantinov represented a veritable

«Yugoslav avant-garde» (Ignjatović). Their international

experiences endowed them with the ability to interpret the nation's

drive for modernization within the realm of architectural design.

In the years following Tange's masterplan, Skopje underwent a period

of remarkable ferment, evolving into what can aptly be described as a

«béton brut cityscape» (Lozanovska 2015). It became

a laboratory for the exploration of brutalist architecture, a movement

that indelibly shaped the city's visage and identity.

The Operative Atlas. Skopje Brutalism_Graphic Biography of 15

Architectures[2] (Tornatora,

Bajkovski, 2019) stands as comprehensive and well-structured

exploration of this architectural heritage, commencing with an analysis

of the original drawings meticulously preserved in the city archives.

This endeavor unearthed hitherto unpublished materials, shedding light

on the complexity and originality of this architectural production and

seeking to establish its rightful place within the architectural

discourse while ensuring its due recognition.

Among these architectural gems, the National Bank of the Republic of

Macedonia (1971-1975), designed by Olga Papesh (1930-2011) and Radomir

Lalovikj (1933-2014), and situated in close proximity to the railway,

stands out as the inaugural structure realized as part of the City Gate

project's final segment.

The Telecommunications Center (1972-1981), (Fig. 4) designed by

another Macedonian architect and painter, Janko Konstantinov

(1926-2010), exhibits a captivating fusion of visionary elements

reminiscent of Japanese metabolist architecture. This intervention

comprises three distinct buildings — the telecommunication

center, the administrative building and the counter hall — all

situated atop a single platform that not only connects these structures

but also defines an urban courtyard. The round form of the counter hall

conjures the imagery of a grand tent with a ribbed roof, supported by

anthropomorphic structural elements, projecting outward and bestowing

upon the building an extroverted character reminiscent of architectural

marvels like Oscar Niemeyer's Metropolitan Cathedral of Brasilia (1970)

or Pier Luigi Nervi and Annibale Vitellozzi's Sports Palace (1957) in

Rome.

Tracing along the banks of the Vardar River, the Commercial Center

(1967-1972) by Zivko Popovski (1934-2007) emerges as the conclusive

episode of the new East-West axis within Tange's masterplan. This

architectural feat represents a pioneering typological structure,

ingeniously fusing commercial spaces — incorporated within a

sprawling multi-level horizontal platform — with preexisting

residential edifices seamlessly integrated into a series of towering

structures.

This complex presents an innovative departure from the conventional

American-style shopping center model. Located strategically within the

city's center, it adeptly resolves the linkage between the

main square and the urban park Zena Borec. Functioning as a diverse

nexus, it orchestrates a network of external and internal ramps,

facilitating pedestrian movement through verdant spaces and connecting

them to the layered urban fabric of the city. A succession of terraces,

akin to authentic urban squares, unfolds a modern reinterpretation of

the traditional Bazaar concept, wherein the thoroughfares pulsate with

commercial activities.

On the opposite bank of the river lies the Macedonian Opera and

Ballet (1972-1981), designed by the Slovenian group Biro 71. It is the

sole structure constructed from the envisioned Cultural Center,

situated at the heart of the city. The Slovenian architects pioneered

an architectural masterpiece reminiscent of contemporary designs that

sculpt form through tectonic modeling of the terrain, akin to projects

such as the City of Culture (1999) in Santiago de Compostela by Peter

Eisenman or the Oslo Opera House (2007) by Snøhetta. The

Macedonian building presents itself as a tectonic metamorphosis of the

land, shaping a new topography where architecture and public space

coalesce, extending to the urban stretch along the Vardar River.

Phenomenological considerations permeate all spaces, maintaining a

rational distribution of functions while delineating plastic forms from

the exterior to the interior.

Lastly, the Museum of Macedonia (1971-1976) (fig.6), designed by

Mimoza Tomić (1929) and Kiril Muratovski (1930-2005), comprises various

exhibition spaces — Archaeology, Ethnology, History —

redefining the topography of a segment within the Old Bazar fabric near

the Kurshumli Han, an Ottoman caravanserai. Through terrain modeling,

the intervention configures a connection device among the diverse

elevations of the existing layered fabric. Here, an architecture of

pure cubes arises along the diagonals. Eliciting Byzantine masonry,

Mimoza adorns the upper portion of the building with white marble

tesserae from Prilep quarries, almost suspending it from the darker

exposed concrete below. This juxtaposition enhances the abstraction of

the cubic volumes, defining both the plan and the elevation. The

contemporary intervention's integration into the ancient Ottoman fabric

is filtered by the roof's design, characterized by dark-colored slopes

contrasting with the white marble volumes. The ridge lines, rotated

along the diagonal, create a new skyline in dialogue with the

surrounding context.

In this itinerary, we cannot overlook the contributions of Georgi

Konstantinovski (1930-2022), a Macedonian architect who completed his

education at Yale University under Paul Rudolph. Notable among his

works are City Archive (1966) and Goce Delcev Dormitory (1969),

representing the early instances of brutalist architecture by a

Macedonian architect on an international scale. These structures have

remained integral components of Skopje's urban fabric, a city currently

undergoing profound transformation, particularly since gaining autonomy

from Yugoslavia.

Over the past decade, the principles outlined in Tange's Urban Plan

and the architectural heritage have faced significant alterations

through the implementation of the "Skopje 2014 Urban Renewal Plan."

Officially announced in 2010 and funded by the previous Macedonian

government, this initiative has, to some extent, been halted, resulting

in a varied development in Skopje's city center. This development has

included the construction of new buildings, bridges, approximately 34

monuments and sculptures, as well as transformation of over 10 existing

structures. All of these interventions are characterized by a

pronounced eclecticism, predominantly manifested in the facades and

exteriors.

In addition to planning new constructions to fill urban voids, the

new plan has initiated actions aimed at erasing the remnants of the

socialist era and transforming the existing architectural heritage.

Eclectic facades, constructed with ephemeral materials, now adorn some

of the city's iconic buildings. Simultaneously, new public structures

have emerged without a harmonious relationship with the urban context.

In particular the Republic Dispatch Center MEPSO (1987-89), (fig.8)

by Zoran Shtaklev as shown in (fig. 8), designed by Zoran Shtaklev,

serves as an example of the transformation of modern architecture. It

was originally characterized by a horizontal cantilevered roof plane

atop a transparent glass volume. However, it has been modified into a

structure that roughly resembles a Greek temple, complete with an

entablature, columns, and a basement.

In the case of the Macedonian Opera and Ballet (1972-1981), (fig.9)

deliberate alterations to the public space between the building and the

Vardar River have been made. These alterations encompass various

architectural interventions, such as additional buildings, monuments,

and sculptures. Collectively, they form an eclectic linear curtain

along the Vardar River, effectively obscuring the original building and

disrupting the urban relationships envisioned in the Tange Plan.

In the case of interventions on the Ss. Cyril and Methodius

University Campus (1970-74), (fig.10), the absence of a clear strategy

has resulted in the placement of new structures in open spaces, thereby

compromising the overall integrity of the campus. This complex,

situated north of the Vardar River, serves as a pivotal hub within the

cultural and educational center outlined by Kenzo Tange's Plan.

In conclusion, the Skopje 2014 project was a controversial attempt

to transform the architectural landscape of Skopje by incorporating

elements and motifs that imposed artificial "neoclassical" styles,

unrelated to the city's history. However, the plan was eventually

halted due to reactions from the cultural community, the absence of

genuine public participation, and the misinterpretation of the city's

heritage. These interventions, lacking a coherent strategy, have

disrupted some of the reconstruction efforts. (fig.11-12)

Within this intricate fabric, the architectural production following

the earthquake continues to exhibit a profound sense of individuality

in terms of spatial and urban characteristics, form, materiality,

craftsmanship, and more. To the extent that the past seems more modern

than the present, this phenomenon transcends mere aesthetics. It

presents a landscape characterized by profoundly modern architecture,

where "beton brut" serves as a plastic material akin to the works of

Giuseppe Uncini, conveying manufacturing processes and materializing a

nexus between substance, form, and structure. The relationships,

principles, and spatial concepts embedded within such brutalist

architecture, while the "utopian" vision of the Tange Plan remains

unrealized, not only represent a legacy of the recent past but also

constitute a wellspring of ideas for the future.

Perhaps Skopje's designation as the Capital of Culture for 2028 can

serve as an opportune moment to turn a new page, harnessing its

historical heritage to intersect with novel design dimensions and

redefine the city's urban identity.

Notes

* The subtitle of this article is inspired by the text of Slobodan

Velevski and Marija Mano Velevska, published in Freeingspace:

Macedonian Pavilion, 16th International Architecture Exhibition

– La Biennale di Venezia 2018.

[1] The City Center of Skopje

reconstruction international competition saw participation from the

following teams: Slavko Brezovski and his team at "Makedonija Proekt"

in Skopje; Aleksandar Djordjevic and colleagues from the Belgrade

Institute of Town Planning; Eduard Ravnikar and associates from

Ljubljana; J.H. van der Broek and Bakema based in Rotterdam; Luigi

Piccinato partnering with Studio Scimemi from Rome; and Maurice Rotival

from New York.

[2] Operative Atlas of

Skopje Brutalism_Graphic Biography of 15 Architectures is a part

of the volume TORNATORA M., BLAJKOVSKI B. (2019) – 99FILES:

Balkan Brutalism Skopje, MoCa, Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje.

This research is an excerpt from Blagoja Bajkovski's PhD thesis,

conducted under the mentorship of prof. Marina Tornatora and

co-mentorship of prof. Marija Mano Velevska at the Faculty of

Architecture, "Ss. Cyril and Methodius" University in Skopje. The

thesis was completed within the Department of Architecture and

Territory (dArTe) at Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, as

part of the XXXII cycle of PhD studies, coordinated by Professor

Gianfranco Neri.

Bibliography

AA.VV. (2013) – Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.

Phaidon, New York.

BANHAM R. (1955) – “The New Brutalism”. In Architectural

Review, n.708.

BANHAM R. (1966) – The New Brutalism. Ethic or Aesthetic.

Reinhold Publishing Corporation, New York.

BANHAM R. (2011) – Megastructure: Urban Futures of the

Recent Past. Harper and Row.

IGNJATOVIĆ B. curator – Contemporary Yugoslav Architecture,

catalogue, travelling exhibition. Belgrade: Federal union of

associations of Yugoslav architects, 1959, nonpaginated.

JAKIMOVSKA-TOŠIĆ M., MIRONSKA-HRISTOVSKA V. (2017) – The

urban concept of Macedonian cities within the ottoman culture, https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1035242.

KOOLHAAS R., OBRIST U.H. (2016) – Project Japan

Metabolism Talk., Taschen, Spain.

KULIĆ V., MRDULJAŠ M. (2012) – Modernism

In-between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia, Jovis

Berlin.

MRDULJAŠ, M. (2019) – Jugoslavia:

l’urbanizzazione e la questione del tempo storico in una

condizione di semi-periferia, in Pignatti, l., Modernità

nei Balcani. Da Le Corbusier a Tito, LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

RIANI P. (1980). Kenzo Tange, Sansoni, Florence.

SMITHSON, A, SMITHSON, P, FRY, M. (1959). “Conversation on

Brutalism”. In Zodiac n.4.

STIERLI M., KULIĆ V. (2018) – Toward a Concrete Utopia:

Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948-1980. New York: Museum of Modern.

TANGE K. (1996) – “Master Plan for

Skopje City Center Reconstruction, Skopje Yugoslavia 1965”. In

BETTINOTTI M. (a cura di) –, Diabasis, Parma.

TOLIĆ B. (2011) – Dopo il terremoto. La politica della

ricostruzione negli anni della Guerra Fredda a Skopje, Diabasis,

Parma.

TORNATORA M., BLAJKOVSKI B. (2019) – 99FILES: Balkan

Brutalism Skopje, MoCa, Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje.