The urban role of architectures and places for decentered

facilities for community health

Giuseppe Verterame

The shock caused by the

recent pandemic has generated a common desire for the renewal of social

policies, which a necessary advancement can be perceived in. Indeed,

between isolation and forced closures, we experienced loneliness,

physical distancing with repercussions on behaviors, and consequences

on social interaction. At the same time, the period of home confinement

highlighted vulnerabilities and strengthened awareness of the

importance of personal relationships within communities, organizing

actions of solidarity to support the most fragile ones providing food,

medicine, and emotional support.

The health emergency has thus highlighted the need to adopt new

approaches to achieve a better quality of life, including a paradigm

shift in public health «moving from a medical model, focused on

the individual, to a social model, in which health is considered as the

result of various socio-economic, cultural, and environmental

factors» (Capolongo, Buffoli, Brambilla, Rebecchi 2020, p. 271).

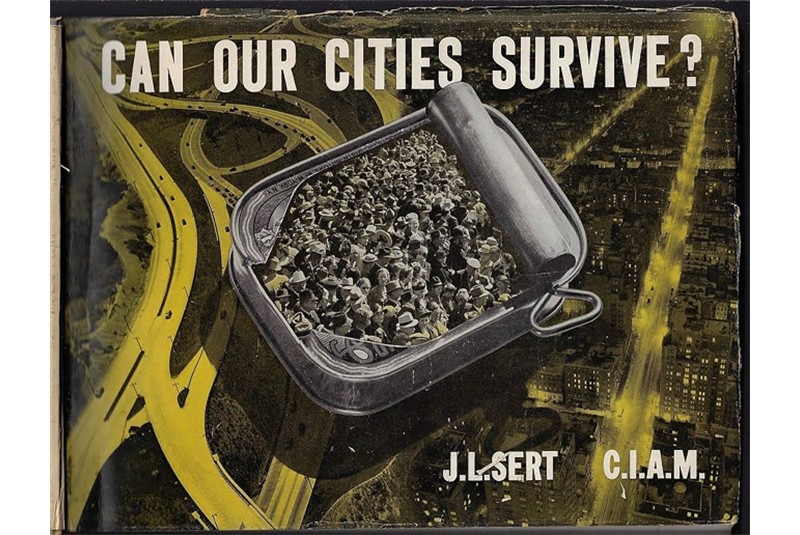

The sudden spread of the virus led to some of the strictest containment

measures in the world within democratic states, adopted precisely

because the healthcare system had evident weaknesses in the lack of

decentralized support to central healthcare structures such as

hospitals themselves.

To rectify the highlighted deficiencies, the Ministry of Health in May

2022, with Ministerial Decree No. 77,1

conceived a new territorial model for the Health Service, introducing

the Community House as the focal point of a network of health and

social services spread throughout the territory. Derived from the

organizational and functional matrix of the Health Houses ‒ which has

found uneven application in different regions ‒ it is characterized by

an integrated and multidisciplinary approach among professionals in the

healthcare, social-healthcare, and social sectors, with attention to

continuity of care and home support, particularly for disadvantaged

groups with new professional figures such as the so-called Community

Nurse.

This model attempts to respond to the need for a paradigm shift

mentioned earlier, which obviously cannot be resolved solely by

adopting new models and standards ‒ as defined by Annex 1 of the

aforementioned Decree ‒ but through a broader vision, first and

foremost one that includes its strategic role towards the city.

For several decades, there has been insistence on the intrinsic

relationship between city and well-being and how the quality of life of

individuals depends on it, since the United Nations Conference on the

Environment held in Rio.2

Recently, in 2021, the Ministry of Health published the Guidance

Document for urban planning from a Public Health perspective, where it

highlights that «the concept of the Healthy City presupposes the

idea of a community aware of the importance of healthcare as a

collective good» (Ministry of Health 2021, p. 6). In this way,

the importance of the urban environment for health is highlighted,

which is not only associated with the individual sphere but correlated

with the community benefit and therefore the idea of community

healthcare (ivi, p. 10).

However, the various recommendations contained in the issued documents

from the Conference to the recent proposals, have mostly become

slogans. Today, beyond some collective facilities, urban renewals of

more or less abandoned areas, cycling tracks extensions and low urban

impact parks, urban regeneration interventions characterized by a

holistic vision capable of restoring a condition of well-being of

strong social relevance are not evident. Once again, the health

emergency has highlighted issues related to collective facilities and

spaces: to many it seemed evident the importance of rethinking the city

‒ during that period denied due to lockdowns ‒ experienced in the

vicinity of one’s home to reclaim that innate instinct for

community and social expression, often disillusioned because those few

and reduced practicable spaces did not have relevant quality.

For community health: the paradigms of

centrality and urban place

The need to start from the city as a collective phenomenon and

geographical field of community phenomenology seemed evident, capable

of ‒ as Jean-Luc Nancy writes ‒ relating singular with plural being,

that is, the scene capable of representing the «good show, the

social or community being [that] presents itself its own interiority,

its own origin (in itself invisible), the foundation of its right, the

life of its body» (Nancy 2001, p. 77). Within the necessary

paradigm adoptable in the post-COVID context, therefore, the theme of

collectivity emerges, a social priority based on the matured awareness

of the importance of the role of the community in a solidarity key, as

manifested by various entities during the isolation period. The

nominalistic substitution from Health

House to Community House,

although carried out only by Decree without resulting in many contexts

in a real change in terms of programming and operational, seems to fall

within that matured awareness by the institutions produced during the

pandemic to which reference was mentioned above. Considering the

present, the advantages of the Community

House would be numerous, particularly in relation to themes of

inclusion and diversity, solidarity and assistance to vulnerable

groups, civic participation and education. Indeed, the community can

represent a key element in addressing social, economic, and health

challenges, as collaboration and solidarity are fundamental to building

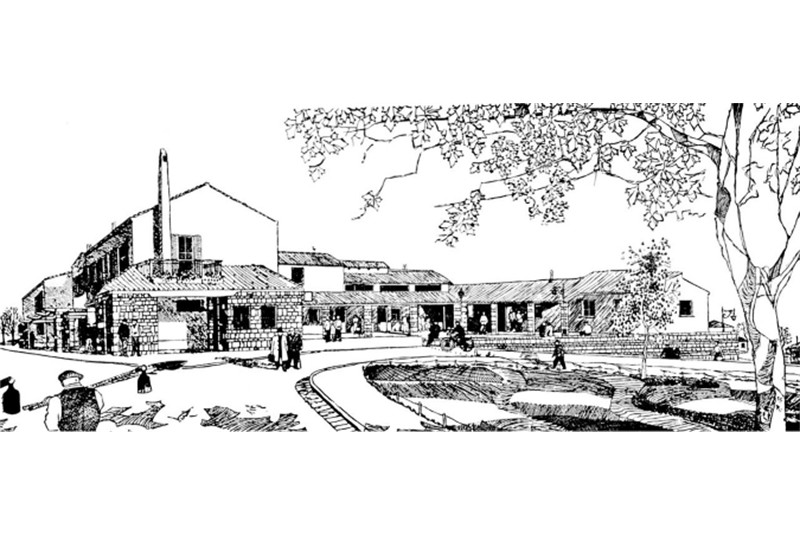

sustainable societies in the long term. Adriano Olivetti claimed the

importance of the Community within society for the construction of

civic sense from the bottom and by focusing on individual

responsibility, social solidarity, dignity and rights of individuals,

interests of future generations (Olivetti 2013). Olivetti applied

community values to different contexts, from rural settlements in

Canavese ‒ with the construction of Community Centers ‒ to the

industrial work context and up to the development of Ivrea, where he

integrated work, residence, and facilities, promoting the construction

of houses, schools, and health service to improve the quality of life

of employees and their families (Renzi 2008). He unequivocally

demonstrated that there cannot be community development disconnected

from a place construction which takes to the idea of city, as scene

,whilst,of Communitas

(Esposito 1998) and Immunitas

(Esposito 2002).

However, among ministerial guidelines, there is no reference to the

urban potential of these models of territorial assistance that possess

the status of public buildings. The critical emphasis does not aim to

be obvious but necessary, considering the meta-design proposals, the

initial projects, and the built examples – also including Health Houses – often lacking

in terms of typological articulation and representative quality within

the urban structure. A forward-thinking and, therefore, sustainable

vision must consider the realization of the Community Houses according to the

typical collective vocation of civil architecture, interpreting it as

the potential community district of a specific part of the city and a

means of community phenomenology.

In addition, architectural and urban mechanism characterized and

adequately equipped in this way can play a crucial role in managing

emergencies that, as demonstrated in the recent pandemic, are

particularly concentrated in urban areas.

Therefore, working on the city with an awareness of the potential role

of its facilities can, on one hand, effectively limit the impacts of

future emergencies and, on the other hand, underline the central role

of the community.

In light of the most significant events, the transformation of the city

is conditioned by the urgency imposed by current affairs, such as the

necessity represented by community health. According to Antonio

Monestiroli, architecture design must experiment with new forms able to

reveal the collective reason behind the themes that unfold throughout

history (Monestiroli 1979, pp. 34-35).

Given these premises, we should now ask ourselves what the reason for

architecture is, in relation to community health, precisely in

connection with the city, which, as Carlo Quintelli (2010a, p. 9)

believes, should be considered

a community structure,

where the mechanisms of reproduction of the whole and its parts tend to

reinterpret and reproduce the community principle as a necessary

confirmation of the urban background, but according to different

declinations and elaborations of meaning.

In this sense, the architecture of community health cannot be

dissociated from its collective dimension, without which it would lose

meaning.

However, the collective dimension is not solely found in the

realization of its practical purposes in response to its main

functions, such as those for health, because we would find ourselves

with a structure that meets functional and utilitarian requirements but

lacks architectural qualities capable of representing its urban role as

a civil building.

Thus, in attempting to interpret the meaning of such a work for the

community, it is appropriate to delve into what Monestiroli (1979, pp.

34-35) sustains:

I believe that the

reason for every building is based on its function, originates from it,

but does not coincide with it. And it is precisely this non-coincidence

that allows the progress of architecture, or at least the progress of

one aspect of it, that of understanding the meaning of each artifact

[…] if we consider function as what links architecture to the

concrete reality in which it is built, we can say that knowledge of the

function occurs through knowledge of reality as a whole. It is not

possible, therefore, to stop at the function as it is, but it is

necessary to know its deep aspects, linked to a more extensive and

general knowledge of reality. It is this knowledge that allows us to go

beyond function and to know the reason for the buildings.

Given certain analytical-critical premises, it is now necessary to

proceed synthetically to the design definition, also analogically, of

architecture for community health in an urban sense.

If you observe the city – especially the suburbs – a

widespread lack of overall characterization emerges, arising from an

evident formal indeterminacy. Within a previously determined state of

necessity, on the one hand, in terms of urban phenomenology and, on the

other hand, sociologically, architecture for community health finds its

reason in being able to represent itself as a factor of urban centrality,3 a collective building, and a

composite architectural device, relevant not only in terms of

functionality and usability but above all for its ability to interpret

its civic sense as urban equipment with predisposition to

multifunctionality, flexible in its various uses, easily accessible,

endowed with open common spaces, and socially contaminable thanks to

the various facilities it can offer.

In this sense, the contribution to the determination of centrality, in

addition to implementing specific functional programs, can promote

exchange and cooperation among various entities and institutions,

generating synergies among the actors involved in promoting health as

well as social interaction, materializing one of the meanings of

community.

The concept of centrality is conceptually appropriate both for the

scale of architecture and for the city one, the physical context

in which the architecture of community health aims to establish

relationships. In this regard, we could evaluate the appropriateness of

adopting the paradigm of urban place to concretely translate that

dimension of centrality which architecture contributes to. Indeed, this

dual character can represent a plurality of organized forms, such as

buildings for various types of activities and services, public or

private – including specialized residences – but at the

same time expresses a unified image, better able to express its

potential urban role as a space for the community.

In this sense, the place represents a complex architectural system,

possesses structural and identitary urban qualities, encourages social

phenomena, and establishes multiple relationships between architecture

and the city. According to Rykwert, the concept of place transcends

rational criteria to reach symbolic aspects to the extent that citizens

can feel pride in belonging to a certain area, so as to develop a sense

of belonging. It is an intrinsic force that influences the sociality of

its inhabitants, activating the vitality of a community. Furthermore,

he argues that the presence of reference places is crucial because it

enriches the urban experience: understood as reference points, they

have a significantly urban role and act as catalysts for human

activities, to the extent of determining a character, through their

representative and distinctive qualities in the urban experience

(Rykwert 2003, p. 306).

Drawing from historical experience, the square is the type of urban

place that best translates the described qualities: in terms of

representation, it is a space endowed with symbolic qualities,

identifiable as a catalyzing void of public and social activities. In

this regard, Paolo Portoghesi argues that it is «indeed the

square, understood as the beating heart of the city, the driving force

and intellect of the urban fabric [...] the privileged place of

encounter, dialogue, and social exchange» (Portoghesi 1990, pp.

13-14). Moreover, he embraces Nancy’s thesis on the

community’s need to represent itself in an urban theater:

stage and theater enter

into the design of the square not as external contributions, but as an

inherent requirement of the very concept of square: a place where the

presence of man, whether daily or linked to particular events, must

become a scene (ivi,

p. 24).

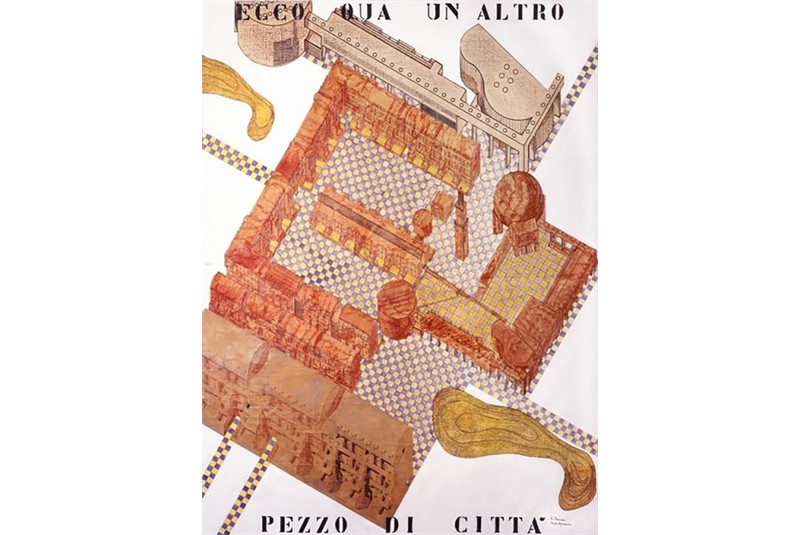

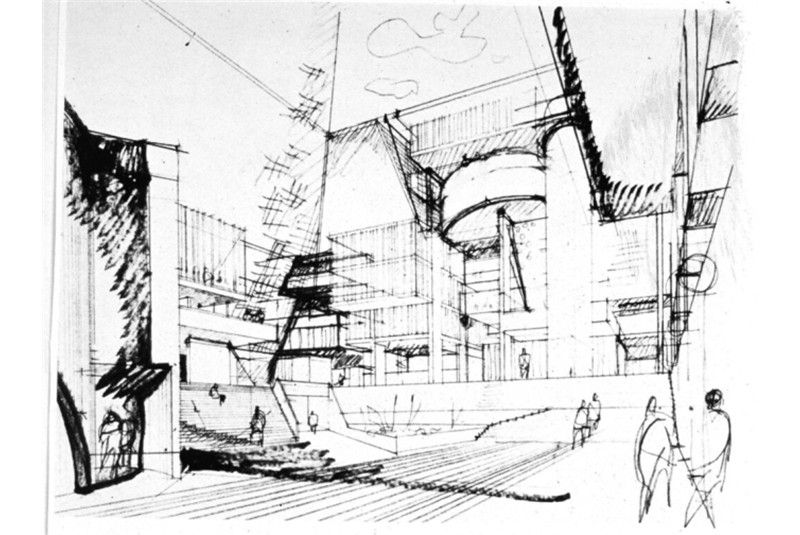

According to Carlo Aymonino, this capability transforms the public

space of the square into an urban fact. He demonstrated this in

numerous square realizations: surpassing the axiom of empty space, he

considered it as «an urban place par excellence» (Aymonino

1995, p.20). He employed one of the archetypal themes of architecture

and city construction through the composition of architectural

plurality, made up of different but converging parts in the expression

of unity, capable of sublimating the concept of place, a conceptual and

relational synthesis between urban structure and architectural

solution. He made this evident in many of his projects: the realization

of schools, residential complexes, theaters, and administrative

centers. The importance of his contribution lies in demonstrating that

architectural design is not only the solution to a single problem

– such as the realization of a building for healthcare purposes

– but the response to a complex issue. As evidence of this, for

the project of the school compound in Pesaro, he recounts that in the

context of the project site, «a central place was missing,

organized for civil life, an architecture that represents it»

thus suggesting

to insert a civic,

political, cultural, and commercial center in the campus, a meeting

place for student segregation and the social reality of the

neighborhood [...] a visible and recognizable reference point of that

part of the city, undifferentiated in its architectural results (ivi,

p. 54).

To exemplify the structural capacity of the urban role of the concept

of place, it may be useful to recall the experience of Ina Casa,

without specifically entering into the detail of realized examples.

More than half a century later, the architectural and urban quality of

those realizations and their ability to become places are still

evident. Many constructed neighborhoods, thanks to their layout, have

managed to generate significant urban relationships, transforming from

autonomous and self-sufficient neighborhoods into urban structures,

thereby facilitating the construction of new cities around them. This

was made possible mainly by the strength of the plural system

characterizing the central place of these neighborhoods, where various

services, activities, and public spaces converged, capable of

triggering identities and strong recognition, even landscape-wise, of

that piece of the city (Boccacci 2010, pp. 124-129).

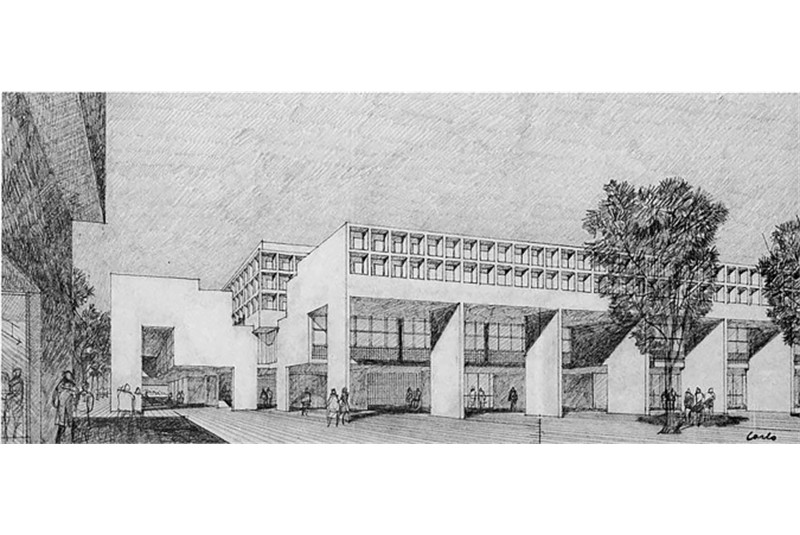

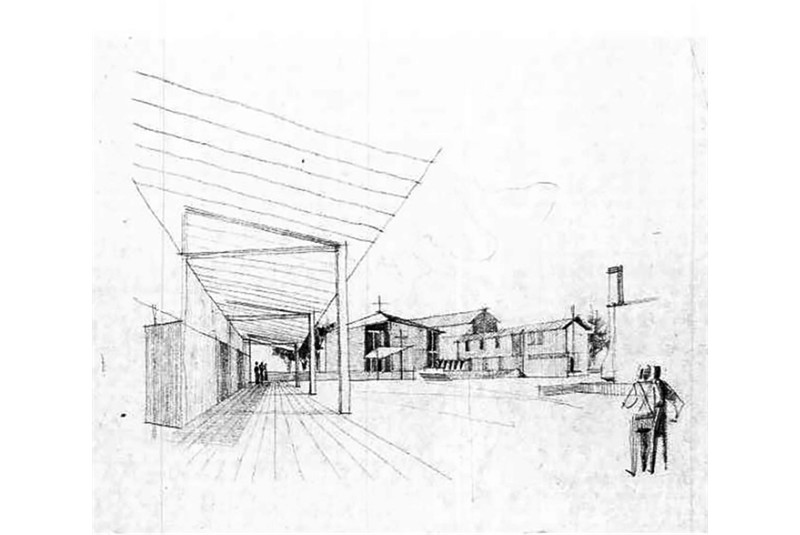

Today, the need to create architectures for healthcare can represent,

following the experiences mentioned above, an opportunity to regenerate

the suburbs, give meaning to their unresolved fragments, and make them

formally complete urban parts. Pre-existing urban elements such as

parks, schools, commercial activities, libraries, can synergize with

the architectural components of community health to create a strongly

denoted place of urban centrality.

Regarding this hypothesis, other scholars, who have recently developed

the theme of the Community House,4 agree on the urban role to be

attributed to the new structures to make them «pieces of a

regeneration strategy aimed at creating new social networks and, at the

same time, capable of substantiating new forms of urbanity»

(Ugolini and Varvaro 2022, p. 29-30).

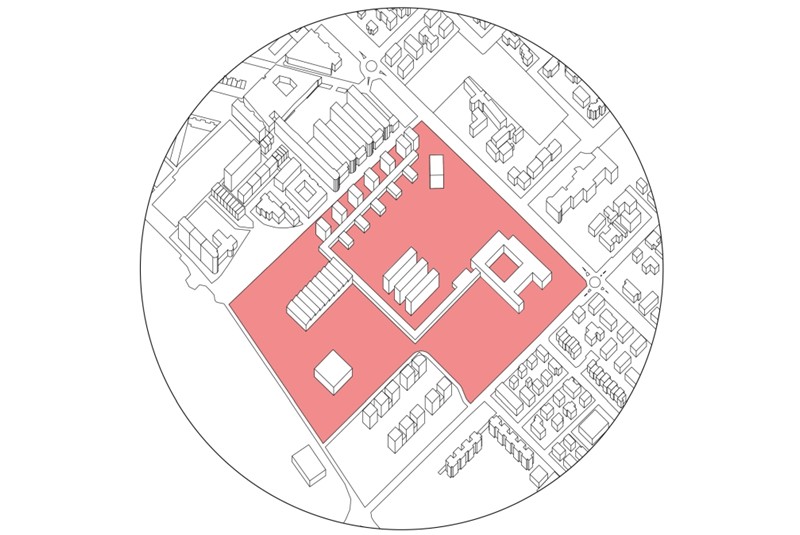

An urban-scale design research hypothesis for Places and Centers of Community Health5

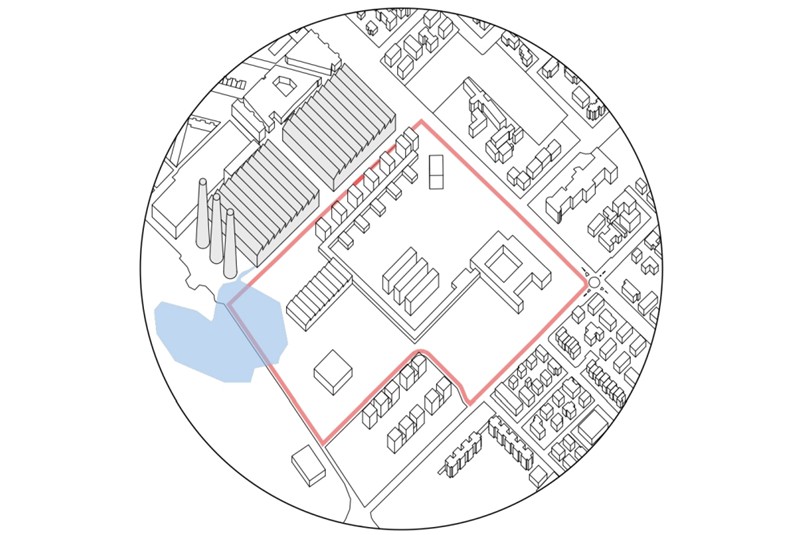

To meet the requirements of representativeness, urban structurality,

and identity characterization through the adoption of the

architectural-urban paradigm described, within the research on new

built typologies for community health conducted by a group from the

University of Parma, some methodological-design tools are hypothesized

to support the prefiguration of places and centers dedicated to these

new developments in the socio-health public service. These are criteria

and indicators for evaluating the settlement qualities of places and centers of Community Health,

supporting their design at the urban scale, even before the

architectural one. In particular, this section, included in the ongoing

research, deals with the strategic relationship between the aggregate

centrality place and the city understood in its structural and

morphological articulation of the neighborhood. For this reason, the

structural aspects of urban space are considered, especially the ones

dedicated to public use and related facilities, designed in relation to

other components of the settlement fabric, infrastructural elements,

green areas, and large equipped voids of collective and environmental

interest.

In summary, the methodology outlined within the research evaluates the

existing urban conditions and resources, including distributive

efficiency, location, relationship with other urban elements, the shape

and size of the project site, accessibility, urban planning

constraints, and potentially harmful conditions for collective health

as well as for the feasibility of implementing the Places and Centers of Community Health.

The methodological tool is developed through the following analytical

criteria and evaluation indicators:

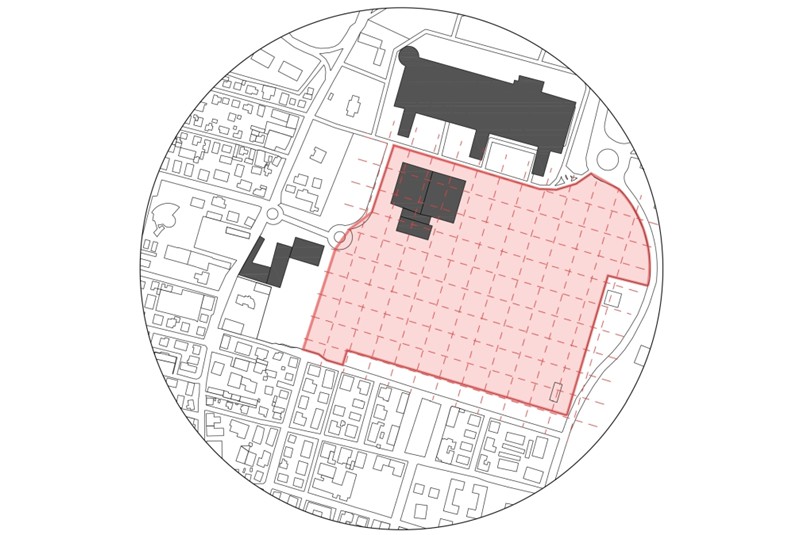

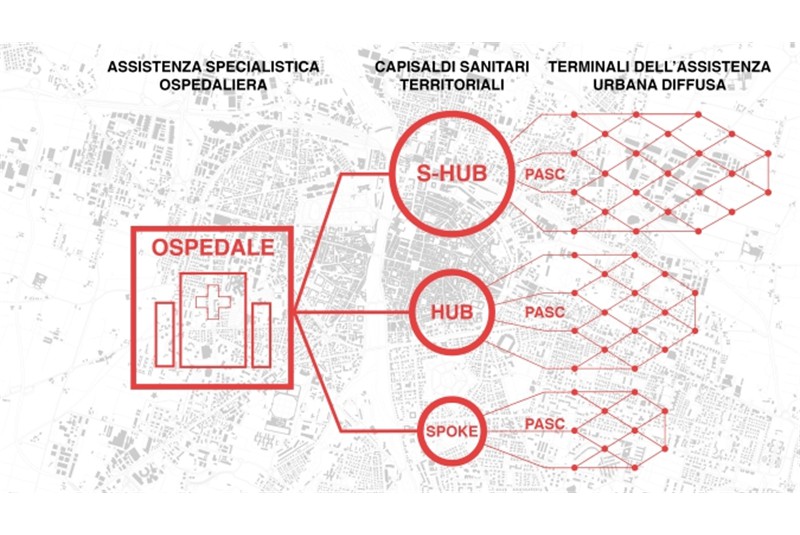

1- Provision and distribution system of Community Health Centers to the

territorial and urban scale: this parameter assesses the distribution

of socio-healthcare service nuclei at the urban and territorial scale

and verifies their distributional balance and capillarity, based on the

scale considered.

2- Position of the area for the Community

Health Center in the neighborhood/urban area: this parameter

highlights the possibility of locating the Place-Center of Community Health in

a suitable position – starting from the baricentric one –

in order to achieve the necessary accessibility, usability, and

recognizability requirements for determining the place and centrality

referred to earlier.

3- Relationship between centrality factors regarding the Place-Center of Community Health

area: this parameter justifies the positioning in relation to the

presence, the capacity for relationship, and prossemic characteristics

of pre-existing centrality factors, such as other public services or

buildings for collective activities and of strong attraction.

4- Dimensional entity of the area for the Place-Center of Community Health:

this parameter verifies the dimensional adequacy of the area in

relation to the possibility of settlement in terms of place and urban

centrality.

5- Formal identity of the area for the Place-Center of Community Health:

this parameter verifies the morphological suitability to capture the

functional, representative, and identity potentials, as well as the

perceptual relevance of the Place-Center

of Community Health.

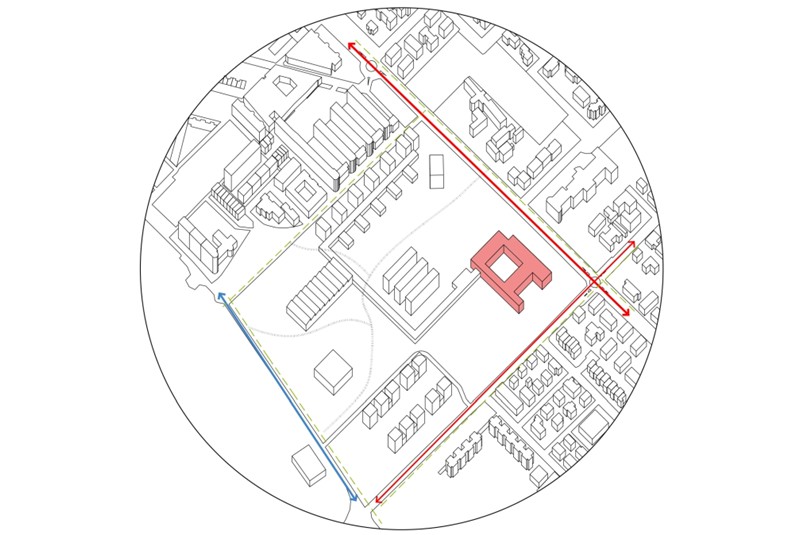

6- Accessibility and mobility related to the Place-Center of Community Health

area: this parameter verifies the presence and effectiveness of various

accessibility modes, particularly those of soft mobility.

7- Negative conditioning factors for the healthiness of the Place-Center of Community Health

area: this parameter verifies urbanistic, environmental, and

infrastructural constraints, as well as other harmful conditions for

healthiness and the feasibility of implementing the Community Health Center.

These above-mentioned parameters are verified through experimentation

on susceptible areas identified within the city of Parma, used as a

case study. The exposed succession allows the parametric evaluation of

susceptible areas and their insertion into an overall analytical

framework from which to deduce synthetically the potential and critical

aspects of design application and experimentation.

The application of the seven analytical criteria and evaluation

indicators produces a ranking divided into four thresholds –

negative, sufficient, good, optimal – which allows defining an

order in relation to various possible susceptible areas, in order to

guide the choices of identifying the areas most congenial to the

realization of Places and Center of

Community Health.

The Places and Centers of Community

Health described so far represent the territorial healthcare

cornerstones of a possibly even broader system of healthcare and social

assistance within the city, if the adoption of Neighbourhood Assistance Points

(NAPs) is envisaged, which are terminals of widespread urban

assistance. In fact, to meet the need for a widespread healthcare and

social assistance system, the introduction of additional facilities is

envisaged, spread throughout the living spaces within the urban fabric,

to support the higher-ranking structures, namely the Community Health Centers.

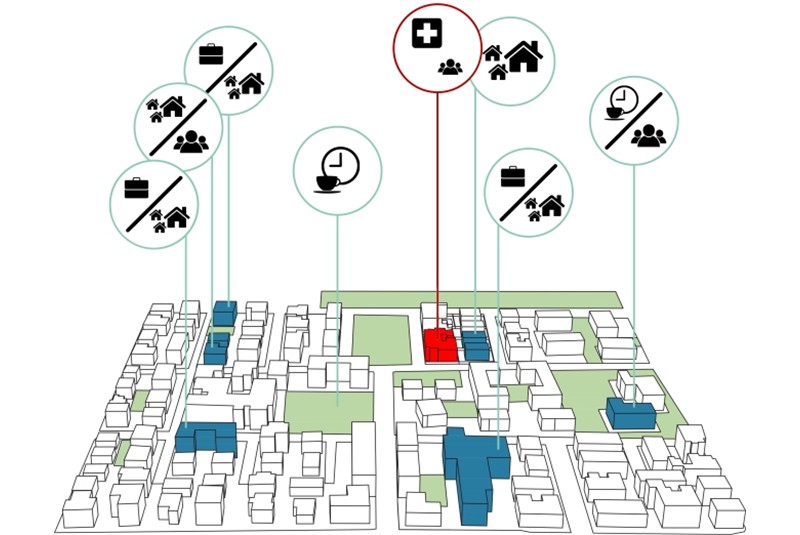

In order to analyze and manage the scale related to the urban fabric,

it is appropriate to introduce the architectural and urban model of the

macroblock,6 useful for the organization and management of a

widespread, capillary urban service strategy that is easily accessible

from residential areas.

The macroblock is a unit of the urban fabric obtained by merging

multiple blocks – the number can vary depending on the

typological-morphological conditions of the blocks and demographic

characteristics – inserted into the overall system of the

neighborhood. It represents an aggregative principle of the urban

organism and constitutes a significant minimum urbanity in terms of

demographic critical mass, which, by involving individual housing units

at the management level, proposes spaces for socialization, rethinks

soft mobility, and experiments with a new organization of neighborhood

welfare within it.

The NAPs, which, for its basic operational role, is congenial to the

usage physiologies of the macroblock, responds to the demand for an

observatory as well as for assistance proximity that adequately

corresponds to the daily needs of individuals in conditions of health

and social fragility, partially self-sufficient and often with limited

access to Community Health Centers.

The NAPs benefits from the presence of multifunctional concierge

services within each macroblock, capable of performing additional tasks

for the urban community, such as reception and information, access

control and security, parcel delivery, maintenance and general

services, emergency management.

In general, the conditions of services and collective spaces within the

macroblock counteract physical and social degradation and promote the

construction of a cohesive community. Additionally, they improve the

quality of life of residents through the introduction of new functions

such as playgrounds, gardens, squares, vegetable gardens, and

pedestrian and cycle paths. Moreover, the inclusion of assistance

services like the NAPs not only contributes to the general well-being

of the population but also transforms cities into healthier, more

attractive, comfortable, and secure places.

NoteS

1 The Ministerial Decree No.

77/2022 approved by the Ministry of Health provides, for the first

time, standards for territorial assistance and introduces new

organizational models, including the Community

House (Casa di Comunità).

2 This is the so-called Earth Summit

and the First World Conference of Heads of State on the Environment,

held in Rio De Janeiro from June 3rd to 14th , 1992..

3 To delve into the concept of urban

centrality, see STRINA P. (ed.) (2023) - The Merged City: A research on the urban

project, Il Poligrafo, Padua..

4 Research “Coltivare

Salute.com” coordinated by Michele Ugolini, Maddalena Buffoli.

5 This is the progress report of the

methodological experimentation of analytical criteria for the

urban-scale design of Places and

Centers of Community Health, within a research project on urban

centralities of community health. The research group Urban &

Architectural Laboratory is part of the Department of Engineering and

Architecture at the University of Parma, with scientific supervision by

Carlo Quintelli, and scientific coordination by Enrico Prandi, along

with Giuseppe Verterame, Alessia Simbari, and Sahar Taheri.

6 The macroblock is developed within

the doctoral thesis VERTERAME G. (2022) – Il macroisolato come strumento della

rigenerazione urbana. Spazi, forme e funzioni per la città di

medie dimensioni, Doctoral Thesis, University of Parma,

supervised by Carlo Quintelli. For a deeper understanding of the

macroblock, see VERTERAME G., “The city in quarantine.

Perspectives on urban regeneration through the experimental model of

macroblock”. In QUINTELLI C., MARETTO M., PRANDI E., GANDOLFI C.

(eds.) (2020) – Coronavirus,

city, architecture. Prospects of the architectural and urban design.

FAMagazine [e-journal], 52-53, pp. 113-119, and VERTERAME G.,

“Interpretations of Centrality: Structuring Fabric Through the

Macroblock Tool”. In STRINA P. (ed.) (2023) – The Merged City. A research on the urban

project, Il Poligrafo, Padua, pp. 192-235.

Bibliography

AYMONINO C. (1995) – Piazze

d’Italia. Progettare gli spazi aperti, Electa, Milan.

BOCCACCI L. (2010) – “Quartieri-città per le case

popolari nell’Emilia della ricostruzione”. In E. Prandi (a

cura di) Community/Architecture.

Documents from the Festival Architettura 5 2009-2010,

FAEdizioni, Parma.

CANNATA M. (2020) (a cura di) – La

città per l’uomo ai tempi del Covid, La Nave di

Teseo, Milan.

CAPOLONGO S., Buffoli M., Oppio A. (2015) – “How to assess

the effects of urban plans on environment and health”. In

Territorio, 73, pp. 145-151.

CAPOLONGO S., Buffoli M., Brambilla A., Rebecchi A. (2020) –

“Strategie urbane di pianificazione e progettazione in salute,

per migliorare la qualità e l’attrattività dei

luoghi”. In Techne. Journal of Technology for Architecture and

Environment, 19, Florence University Press, Florence, pp. 271-279.

ESPOSITO R. (1998) – Communitas.

Origine e destino della comunità, Einaudi, Turin.

ESPOSITO R. (2002) – Immunitas.

Protezione e negazione della vita, Einaudi, Turin.

MENDES DA ROCHA P. (2021) – La

città per tutti. Scritti scelti. A cura di Gandolfi C.,

Nottetempo, Milan.

Ministero della Salute (2021) (a cura di) – Documento di indirizzo per la

pianificazione urbana in un’ottica di Salute Pubblica,

MONESTIROLI A. (1979) – L’architettura

della realtà, Clup, Milan

NANCY J.L. (2001) – Essere

singolare plurale, Einaudi, Turin.

OLIVETTI A. (2013) – Il

cammino della comunità, Edizioni di Comunità, Rome.

PORTOGHESI P. (1990) – La

Piazza come «luogo degli sguardi». A cura di Pisani

M., Gangemi, Rome.

PRANDI E. (a cura di) (2010) – Community/Architecture.

Documents from the Festival Architettura 5 2009-2010,

FAEdizioni, Parma.

PURINI F. (2000) – Comporre

l’architettura, Laterza, Rome-Bari.

QUINTELLI C. (2010) – “La comunità dello spazio

progettato”. In R. Cantarelli, C. Quintelli (a cura di), Luoghi Comunitari. Spazio e società

nel contesto contemporaneo dell’Emilia occidentale,

FAEdizioni, Parma.

QUINTELLI C. (2010) – “Comunità/Architettura”.

In E. Prandi (a cura di) Community/Architecture.

Documents from the Festival Architettura 5 2009-2010,

FAEdizioni, Parma.

QUINTELLI C., Maretto M., Prandi E., Gandolfi C. (a cura di) (2020)

– Coronavirus, città,

architettura. Prospettive del progetto architettonico e urbano.

FAMagazine [e-journal], 52-53.

RENZI E. (2008) – Comunità

concreta. Le opere e il pensiero di Adriano Olivetti, Guida,

Naples.

RYKWERT J. (2003) – La

seduzione del luogo. Storia e futuro della città,

Einaudi, Turin.

SETTIS S. (2020) – Città

senza confini? In Cannata M. (a cura di), La città per l’uomo ai tempi

del Covid, La Nave di Teseo, Milan.

STRINA P. (a cura di) (2023) ‒ La

Città Accorpata. Una ricerca sul progetto urbano, Il

Poligrafo, Padova.

UGOLINI M., Varvaro S. (2022) – “The Community Healthcare

center as engine of urban and social regeneration. A post Covid-19

public space design. Health Citadel and Community Center in Fiorenzuola

d’Arda”. In UPLanD. Journal of Urban Planning, Landscape

and Environmental Design, 6(1), pp. 13-34.

VERTERAME G. (2020) – “La città in quarantena.

Prospettive di rigenerazione urbana attraverso il modello sperimentale

del macroisolato”. In Quintelli C., Maretto M., Prandi E.,

Gandolfi C. (a cura di) (2020) – Coronavirus, città, architettura.

Prospettive del progetto architettonico e urbano. FAMagazine

[e-journal], 52-53, pp. 113-119.

VERTERAME G. (2023) – “Declinazioni della

centralità: strutturale il tessuto attraverso lo strumento del

macroisolato”. In Strina P. (a cura di) (2023) – La Città Accorpata. Una ricerca sul

progetto urbano, Il Poligrafo, Padova, pp. 192-235.