When we consider the genesis

of organized welfare structures we have necessarily to start with the

hospital founded by Basil, future holy bishop of the city of Caesarea,

now Kayseri in Cappadocia, Turkey. Built extra moenia with an adjoining

church and monastery, it came into being around 370 in close relation

to the Basilian monastic conception, which flowed into a rule that

predated the Benedictine one by about two centuries; this rule was

aimed at the spiritual and physical care of the person as one of the

most edifying Christian acts. The idea of creating places intended for

care cannot be separated from the idea of the good Christian who must

care for the soul and at the same time fot its container, according to

that doctrinaire reference to Christus

medicus that, from a hagiographic point of view, will find

fulfillment in the “medical saints” Cosmas and Damian. In

pre-Christian antiquity there were, of course, places for the care of

the needy, but it was mostly run by families with rare cases of partial

communal management of slaves or wounded soldiers returning from

endless military campaigns.

What jumps out at us regarding the first organized experiences that we

label for convenience “charitable” in the centuries of late

antiquity and throughout the early Middle Ages is the, we would say

today, polyvalent character of the services offered. The earliest

xenodochia, whose etymology, not surprisingly, refers simply to a kind

of “refuge for strangers,” in the evidently all-Christian

sense of unselfish welcoming to all, offered help to various types of

“needy” people: certainly the sick, but also the poor,

those with ambulation problems, the elderly, orphans, beggars and, of

course, with great fortune in later centuries, pilgrims. It is

necessary, however, to wait until the end of the 8th century, with

Alcuin bishop of York, to be certain of the substantial coincidence

between xenodochia, hospices and hospitals, suggesting a linguistic

division that was not easily found in the factual context. For these

centuries, and basically until the High Middle Ages, we are not able to

identify architectural specificities, except by resorting to purely

monastic models, with the caution, however, that the planimetric

typology of the monastery consisting of a church, cloister on one side

and adjoining spaces around it is a model that is substantially

established in the late Carolingian period, leaving a textual and

archaeological gap that is difficult to recompose for the previous half

millennium. Since Pre-Carolingian monasteries were admittedly

fenced-off places, tending to be isolated, although mostly visible,

away from or on the periphery of towns, in which monks lived in

separate spaces with the exception of the church, we must imagine that

the structures that housed monks were the same as those that housed the

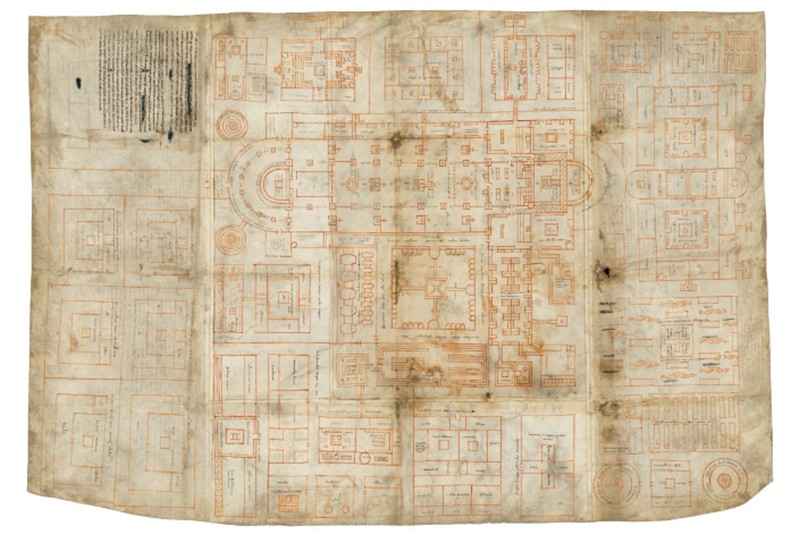

needy. This at least seems to be suggested by the celebrated plan of

St. Gallen (Fig. 1), from the first quarter of the ninth century, a

plan that is more ideal than real, but nonetheless useful for reasoning

about the spaces of a Carolingian monastic complex and thus of all

Europe ruled by Charlemagne. The infirmary, houses for traveling monks,

important guests, pilgrims and the poor are shown, as well as the

bathhouse, kitchen, medicinal plants, doctors’ quarters even the

salassium room.

In the literature, the two fundamental step changes are that identified

between the the end of twelfth and the thirteenth century and that of

the fifteenth century, actually as a long wave of the Black Death of

the mid-fourteenth century. In the first case there is an exponential

increase in foundations for assistance in Europe, an increase dictated

by new general conditions (the so-called Revival of the 12th century),

conjunctural ones (the increase in the number of pilgrims with the

Crusades), and political ones, in reference to a greater number of

actors at play. No longer are there only the Benedictines, their

Cluniac “spin-off”, and the bishops to carry the burden,

but now we can also encounter new orders such as the Cistercians, the

Premonstratensians, monastic-chivalric orders such as, precisely, the

Hospitallers of St. John, and finally, in the decades at the turn of

the 1200s, the Humiliati and then the beghine movement, and immediately

afterwards the mendicant conventual orders, Franciscans and Dominicans.

Among the actors in play, in the 12th century the laity also entered

powerfully, both in the communal and proto-state forms of the great

European powers, but also in new forms of Christian evergetism by which

the setting up of a welfare structure no longer had anything to do with

the Christian spirit and became mostly only a public manifestation of

power, resulting in the rise of a new secular sanctity between the late

12th and 13th centuries, a phenomenon on which André Vauchez has

written seminal pages. However, the 12th century is also unanimously

considered the temporal range of the rediscovery of the centrality of

the city. The effects are immediate: cities become wealthier, the

greater the attraction of population, hence greater problems of care

management, consequence: exponential increase in the number of hospital

facilities. It is no coincidence that the Salerno Medical School

reached the height of prestige in the 12th century, and by the first

decades of the 13th century physicians wanted by the municipality

appeared for “collective” care.

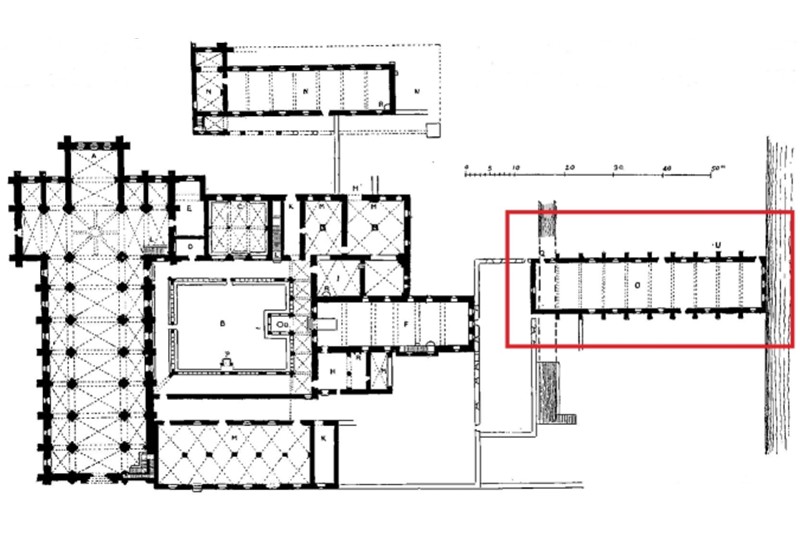

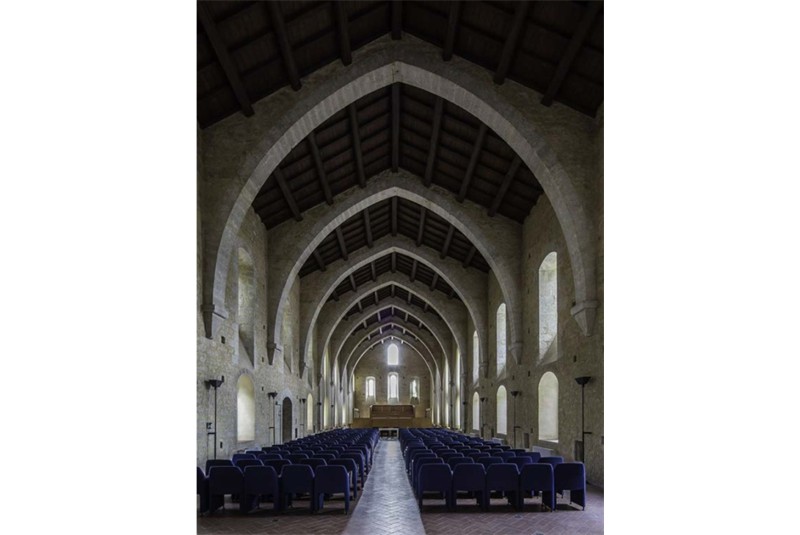

However, this does not mean that hospital facilities became

“medical clinics.” The earliest Benedictine survivals in

relation to infirmaries or spaces for care in general date from the

12th/13th centuries, but it is evident, as in the case of Canterbury,

Ourscamps or in Fossanova itself (Figs. 2-3), the dependence on church

and monastic planivolumetric models in general. It is precisely in

these phases, however, with the renewed and intense involvement of the

laity, that the typology of the hall hospital begins to gain strength,

which Fabio Gabbrielli (2020) specifies has nothing to do with the

various Hallenkirchen models and rather we need to think of

quadrangular spaces, whether or not divided into two or three naves,

covered variously with exposed trusses or vaults, and very

longitudinally developed with the only addition of a chapel inserted in

the perimeter itself or in the immediate vicinity.

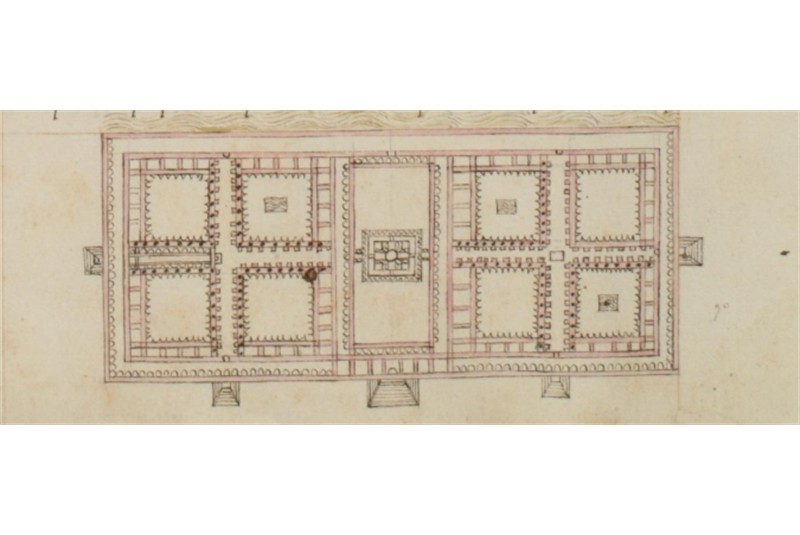

It’s now accepted fact that there is a connection between the

great health crisis caused by the plague epidemic of about the middle

of the fourteenth century and the great second change of pace, that of

the late fourteenth/early fifteenth century, with the emergence of new

mammoth structures (hence the various “Ospedale Grande” or

“Maggiore”) that saw the fixed presence of physicians (or

apothecaries), gradually abandoning the multipurpose as well as

polycentric character of care facilities that had characterized the

reception system in the previous thousand years. This is

counterbalanced, as is well known, by a different architectural model,

the so-called cross-shaped layout (Fig. 4), a layout on which many

scholars have focused in recent decades in order to understand

primarily its origin-from Pavia, from Milan (Fig. 5), from Brescia,

from Florence...-and, above all, its design intention. In general, the

plague had taught that the dispersion of care spaces had not optimized

the response to the pandemic. Having myriad locations scattered

throughout the territory had proven ineffective, no matter how

strategically located or along obligatory thoroughfares. The response

was therefore a concentration of welfare facilities, now less

multifunctional, certainly more specialized, and tending to be linked

to a secular power no longer the almost exclusive preserve of the

Church or religious orders (Figs. 6-7). However, it is clear today that

the “Great Hospitals” model had not been applied

uncritically; on the contrary, where it was understood that the

specific conditions of a city or territory led to the strengthening of

the old model of widespread welfare architecture there was a tendency

to optimize the coexistence of new and old systems.

Tapping into architectural history as a catalog of solutions on which

to set new design systems, as is well known and, I might add, obvious,

is a very delicate operation. It becomes an almost foolish operation to

assume for other contexts the “geometry” of an

architectural complex designed for a specific space and time, with as

many specific needs and purposes: the risk of the “Las Vegas

effect” is just around the corner. These obvious considerations

become perhaps more pregnant if we think of architectures dedicated to

care in a broader sense; I find it more intriguing, if anything, to

question the reasons for the choices that from time to time determined

individual projects, to investigate the religious and

“political” actors at play, to study spatial innovations

under equal environmental conditions, to collate different projects. A

PRIN entitled At the Origins of

Welfare (13th-16th Centuries). Medieval and modern roots of the

European culture of assistance and forms of social protection and

solidarity credit. was dedicated in 2015 as general reflection,

including architectural reflection, on these issues. Well, although

studies on the medieval and early-modern welfare system were not

lacking for the Middle Ages as much from a historical point of view as

from an architectural history point of view, a general (and global)

reconsideration of the issue has contributed in the very last few years

to the publication in Italy and elsewhere of miscellaneous volumes

that, if on the one hand, offer broad reconstructive scenarios of the

origin of welfare systems (Bianchi 2020, also for its impressive

bibliographical apparatus, has become a reference text to be

complemented by the very recent Barceló Prats 2023), on the

other hand, through specific case-studies (e.g., Siena, on which

Gabbrielli 2023 most recently reports), a perhaps too ideological

conception of the problem of medieval and modern care practices has

been partly reshaped in favor of a more specific analysis of contexts.

And one of the outcomes that such specific research has strongly

suggested is that at some point at the end of the Middle Ages, there

emerged enterprises, we would say today, mutatis mutandis,

“private state-sharing” designed for public welfare (Figs.

8-9). These were structures certainly connected to ideals of propaganda

and self-promotion of the ruling classes, but at the same time, without

going so far as to arrive at an overly idealized image of welfare

between the medieval and modern ages, connected to the revolutionary

idea for those times that the greater the number of people in a given

territory who could have decent standards of care, the greater the

wealth and general welfare.

This aspect certainly deserves all the attention because it projects

the care issue, already in the Middle Ages, in a dimension that goes

beyond the architectural, anthropological, social or banally health

issue. The discussion of possible medieval and modern models or

antimodels, in order to have useful repercussions on the most recent

design solutions tending toward integrated systems of care starting

from an urban scale, should focus on the problem not so much and not

only of efficiency, which is certainly an inescapable aspect, but also

on the question of the real impact on the daily well-being of a

community. It seems to me that this is the real bottom line: no

architectural model in almost two thousand years has solved the issue,

but multiple models adapted to individual territorial contexts has led

to increasingly satisfactory outcomes. While it is clear that Community Health Places and Centers

recall, at least on paper, the earliest late medieval and early

medieval multifunctional hospitals, they depart from them in their

polycentric character, based on spatial distribution in a given

territory, which could invariably have been lowland, sea, road, coastal

or river town or valley territory. In contrast, the “spatial

thickening” of the late medieval and modern Ospedali Grandi, the model of which

is sometimes still applied, concentrated care on the urban level, but

the extreme medical specialization caused all other equally necessary

services to the person to be lost sight of, diluting them into rivulets

with little or poor communication between them.

Bibliography

ALBINI G. (2017) – “Pauperes recreare: accoglienza e aiuto ai poveri nelle comunità monastiche (secoli VI-XI)”. Hortus Artium Medievalium, 23, 490-499.