If we wanted to consider the

Health Houses, now Community Houses, among the

«new dominant themes» of the contemporary city –

paraphrasing the epochal scansion of architectural typologies in urban

construction according to the art historian Hans Sedlmayr at the

beginning of the 20th century (1967 ) – we certainly could not

find a significant case study of structures designed and built,

remaining in the Italian context, nor a theoretical or applied research

that could offer us a first framework of reference useful for the

design of these new public works.

This consideration takes on particular importance in the face of a

political planning dynamic, that of the PNRR, a direct emanation of the

Next Generation EU, capable of investing huge resources in the creation

of new centers intended for the need for decentralized health services,

in a broad sense and in direct correspondence with the urban and

territorial settlement.1

It therefore seems appropriate to ask: when in recent history have so

many resources been made available to create public service buildings

in such a short period of time and in a systemic manner at a national

level? We should go back to phases of strong expression of State

planning in the field of public works, such as in post-unification

urban construction or in the twenty years of fascism, net of first

statist and then dictatorial rhetoric, up to a post-war reconstruction

of long inertia between the 1950s and ‘60s, in that case rich in

international reference models towards which Italian architecture

looked with critical capacity and through a process of original and

anti-rhetorical contextual declination where the city is taken as the

primary interlocutor (Canella 1982). Emblematic in this sense is

Olivetti’s project of valorising the community meaning at the

level of work but also educational, cultural and last but not least

health well-being, capable of permeating all components of urban life

thus overcoming the boundary between public and private in the search

for a ethics as well as a shared social utility.2

In general, these are historical phases where, through different

methods and outcomes, the desire to support the construction strategy

of public architecture emerges through design culture tools that have

characterized not only the building itself, from the point of view of

the innovative relationship between form and function, but also, no

less, of the contribution to the transformation of the urban structure,

of its landscape, through the definition of new collective places to

increase the social and civil value of the city.

If we then ask ourselves about the epistemic reasons for an

architectural design capable of applying itself to the theme of health

so strongly solicited by the recent pandemic experience, the starting

point can only be that of Ministerial Decree 77 (2022), which not only

gives specific contents to an implementation strategy for basic health

facilities across the entire national territory, something almost

unique in Italian history, but above all it characterizes and combines

the function of health with the sense of community, once again in the

historical dialectic between Gemeinschaft

and Gesellschaft, between

individual bonds and social contractuality (Cantarelli, Quintelli,

Prandi 2009).

The definition of «Qualitative, structural, technological and

quantitative standards relating to territorial assistance» of

Ministerial Decree 77 therefore constitutes the further push towards a

model which in the Casa della Salute

was limited to purely medical provision while with the Casa della Comunità the

provision performance expands and diversifies, significantly

transforming the very identity of the structure.3 A decisive step forward, long prefigured but now well

characterized, which involves the evolution of healthcare practices in

terms of prevention, active medicine, operational coordination that

multidisciplinarity can determine around the figure of the complex

patient, and last but not least the statistical forecast included

within management planning. A medical dimension integrated with that of

social assistance, consultants, different services which however

compete with an idea of welfare where health refers in a general sense

to the individual person and not just to the living body affected by

pathology. The common denominator for all these components, to be

brought to the maximum level of physiological expression, appears to be

that of the community dimension, at the same time the cause and effect

of a new concept of health rooted in the social body of the city, in

the neighborhoods and between the houses.

Faced with this metamorphosis of the primary healthcare model -

expression of a shared policy at a European level4 in the absence of references, experiences, tools of

urban architectural planning the need for which is evident in order to

be able to deal with typological and settlement interpretations where

the concepts of health and of community overlap with those of

functional space, public place, environment and landscape of the city,

the role of research in an architectural and urban sense emerges more

than ever, complementary to those of a healthcare and welfare,

management and, up to to date, only mainly construction. The one

undertaken by a group of teachers, researchers, doctoral students from

the University of Parma5 which starts

from the only preliminary material available, promoted by the

ministerial agency Agenas, entitled Guideline

document for the meta-project of the Community House by

researchers of the Polytechnic of Milan (Capolongo 2022). An effective

technical framework with the aim of «supporting strategic

management, technical offices and designers in the planning and design

of new Community Houses, Community Hospitals and Territorial Operations Centres»,

where the main qualitative and quantitative data are clarified, the

device mechanisms, the functional organization, the typical

distribution matrix and other parameters for the functioning of the

structures for which the typical recommendations of a logistical,

technical-sanitary and technological-constructive approach prevail.

The part of the document concerning the theme of architectural spaces,

of the typo-morphological variables that can interpret a functional,

but above all fruitful, complex device appears more generic and of

relative capacity for direction, where the formal, figurative, iconic,

chromatic and no less relational which significantly affect the

responsibility of the project and consequently the overall quality of

the architectural structure to be built.6

Nicoletta Setola’s (2022) concise contribution on a role of

architecture that must start from the urban dimension of the

neighborhood and then unravel in the building’s environments

according to methods largely borrowed from healthy buildings and

evidence-based design of the Anglo-Saxon school appears more detailed

in certain respects. That is, from methodologies of a scientific

nature, however substantially extraneous to a formal interpretation of

the architectural space recalling a much more complex conjugation of

factors, starting from those of a contextual nature.

It is not surprising that the architectural component that should be

part of the apparatus of organizational, material and human

instrumentation for care, is however not included among the thematic

categories of the detailed comparative analysis of primary care in the

various European countries carried out by our national health

authorities.7 Paradoxically, this

lack of attention instead sees very different testimonies in other

fundamental sectors of the public service, in particular in the field

of schools as evidenced by the extraordinary historical architectural

case studies and the most advanced research since the first training,

that of childhood so close to the dimension of care, where the

experiential and educational function of the environments significantly

involves the architectural responsibility within educational projects

(Prandi 2018).

It is therefore now a question of focusing attention on the competing

aspects that signify the community and civil value of an architecture

called to distinguish a new generation of health services in a social

sense and also of territorial decentralization. One that should borrow

only in part from technical hospital experience to seek its own,

relating to a medicine close to people in terms of services but also of

cultural belonging, of effective sharing, with respect to which it is

fundamental, among other things, a specific quality of the forms and

relational logics of the spaces to be adopted, according to that

contribution of competence which, evidently, belongs to architecture.

Even historical experience, capable of providing causal presuppositions

and analogical support for research prefiguring the future, would seem

to suggest attention not so much or only to the models of industrial

modernity where the architecture of health has developed typological

machines dedicated mainly to production efficiency of care, relating to

bodies rather than people,8 but also

to a proto-health era, starting from the re-foundation process of the

city at the end of the early medieval period.

In fact, in that historical context of the revival of exchange circuits

between city and city, already typified on a European geography, we

find structures indirectly suitable if not specialized in hosting the

first organized forms of care and assistance which, as Guido Canella

observed, express a «widespread articulation, directly and widely

in contact with the established community» according to spatial

logics capable of putting «the most varied humanity into

contamination», thus verifying the «dialectical return in

the body of architectural and urban planning facts» (1979) which

the contemporaneity of social reasons and community of the topic still

requires us to reconsider and evaluate thoroughly. These are xenodochi,

predominantly free reception and assistance spaces for foreigners,

pilgrims but also poor and fragile people, capable of restoring in a

nutshell the sense of a virtuous conjugation between the actions of

solidarity and those of care to which, mutatis mutandis, today we go

back to look. A useful reflection in conceiving the lines of research

of a design that wants to regain the social meaning of healthcare that

we should hopefully attribute to a Community

House. Starting from these assumptions, as well as from the now

urgent need in the face of the PNRR programming, to fully involve the

contribution of architecture in this important theme, a group from the

University of Parma intended to carry out a research entitled: From House of Health to that of Community,

up to the Places and Centers of Community Health: a strategy of

direction for architectural and urban design, with the aim of

providing some operational as well as conceptual tools projected into

the continually evolving perspective on the role and identity of the

Community Houses, underlining their socially productive meaning as well

as belonging.

A research perspective where the two spheres of the interpretative

problem that addresses the thematic conjugation between health and

community, according to a semantic as well as phenomenological

reciprocity, recall as many categories of the project, first and

foremost of a scalar and typological as well as functional order.

One concerns the role that these new decentralized structures determine

within the city or nuclei of the urbanized territory, conditioning the

potential for urban significance in places of public space, in the

morphological, functional structure and social representativeness.

The other focuses on the architectural organism as a spatial device

capable of interpreting the complexity of the interrelationships

between social and healthcare components to the maximum degree of

synergy and valorization of the actors and foreseen situations.

Both categories are connected and are brought within a single

analytical and proactive process: that of architectural and urban

composition as the primary tool in the design of buildings and places

in the city, in particular if of a public nature and of high social

significance.

The urban dimension of the theme highlights, in dialectic with the

typological entity of the building understood as a Center for public

services, the need to conceive first of all a Place of Community

Health, according to design criteria that serve to overcome the

contingent and occasional logics through which abandoned and

convertible areas or structures in the urban fabric are often

identified when it is planned to build a Community House.

Alternatively, at least as regards the Italian and European context of

a city that still maintains a formal structure based mainly on the

principles of morphological concentration and settlement polarization

on the territory, a correct design approach would require a primarily

positional strategy at the urban and neighborhood scale to cover the

respective geographical settlement extensions, identifying the existing

potential in terms of accessibility, in particular cycle-pedestrian

accessibility and public transport, in relation to green and public

spaces, seeking the maximum degree of complementarity with primary

services, first and foremost public but also private such as the

commercial one, frequented by citizens. Therefore contributing to the

characterization of a place of integrated services, not only

healthcare, aimed at citizens, for the different needs of the elderly

and disabled, young people and women, families, in general for the

quality of life within a neighborhood or an urban part capable of

recognizing itself in a community form. Adopting in these terms an

extended concept of health, aimed at both individual and collective

well-being, where the factor of spatial quality, primarily urban as it

is intrinsically social, cannot help but significantly impact the

functioning of services but also on the sense of belonging, on the

representativeness , on the processes of aggregation and inclusion of

inhabitants who are at the same time actors and users on the scene of a

place felt as their own.

Conformed spaces which, by virtue of these requirements, take on the

value of real urban centralities in the different spatial typologies

clearly perceived such as square, street-square, junction, urban

campus, etc. etc. to be prepared within the neighborhoods as tools to

arm with regenerative factors (Ugolini 2021) parts of the city often

devoid of areas of life and social representation, increasingly

replaced by shopping centers alone.

The characteristic of the architectural project understood in an urban

sense, through the placement of health and social services in the built

city, therefore constitutes a methodological a priori for the full

achievement of the objectives already expected today regarding the Community Houses.

The typological dimension of the theme instead concerns architecture at

the scale of the building, where it is not only a question of

distributing but also of enhancing the characteristics and

relationships between the health and social services provided according

to a strictly complementary perspective. A spatial articulation capable

of encouraging interprofessional exchange from which transdisciplinary

practices characterizing a real socio-health community laboratory can

arise (Quintelli 2023a).

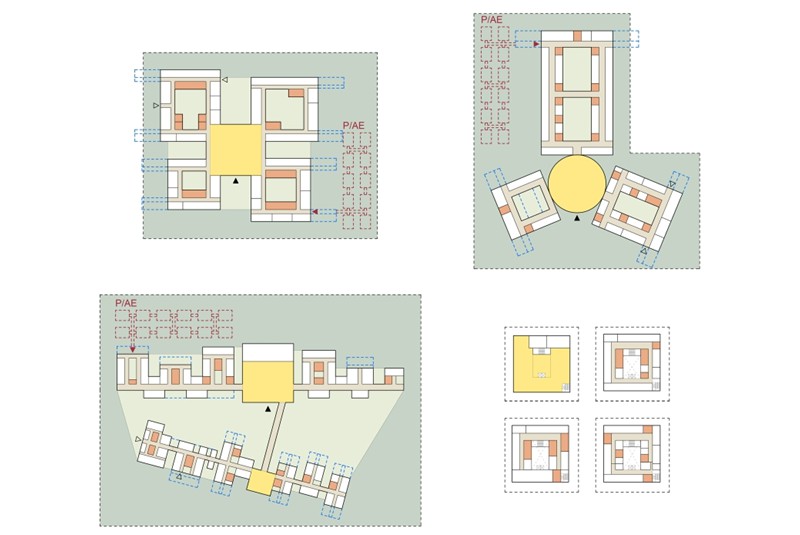

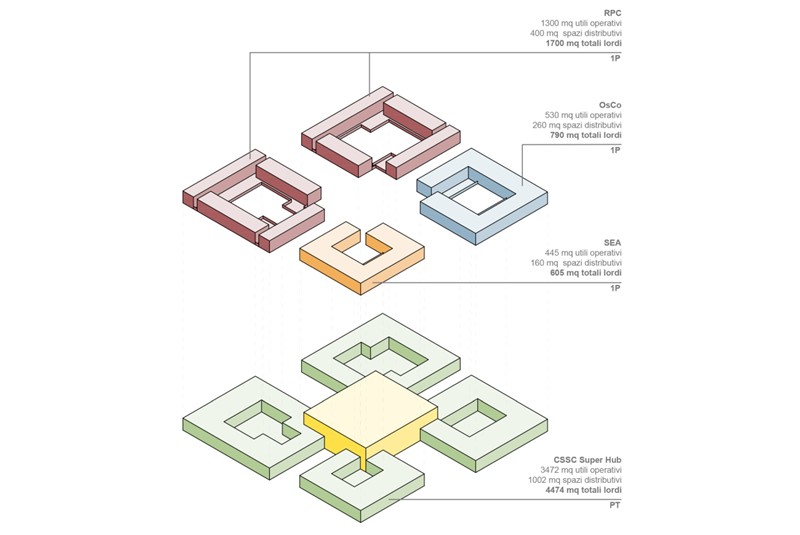

Moving on the level of typological sizing, and taking as reference the

categories of Community Houses

indicated by Ministerial Decree 77 then taken up in the aforementioned

Agenas-POLIMI document, the UNIPR research on Social-community Health

Places and Centers aimed to add to the Hub model (indicatively

dedicated to a catchment area of approximately 40,000 population-users)

and the Spoke (for approximately 20,000 population-users), that of the

SuperHub (for 70/100,000 population-users) as a further entity of

extra-hospital territorial coverage particularly equipped with services

specialized, for example regarding first aid and emergencies, both for

health and social needs. A typological endowment whose scope of

performance and service can therefore oscillate, in size and

complexity, from the scale of the neighborhood to that of an entire

urban sector.

Thinking in particular about the SuperHub, but not only, it seems

logical to remove this type of structure from the domestic and

individualistic identity to which the term “House”

metaphorically alludes, also renouncing certain easily agreed-upon

protective and consolatory suggestions, in favor of the name of Community Health Center. A Center

that highlights the collective and participatory dimension of the

citizen users, the performance caliber and the qualitative guarantee of

the services offered, as well as the public representativeness of a

space with high community value in the city in which one lives.

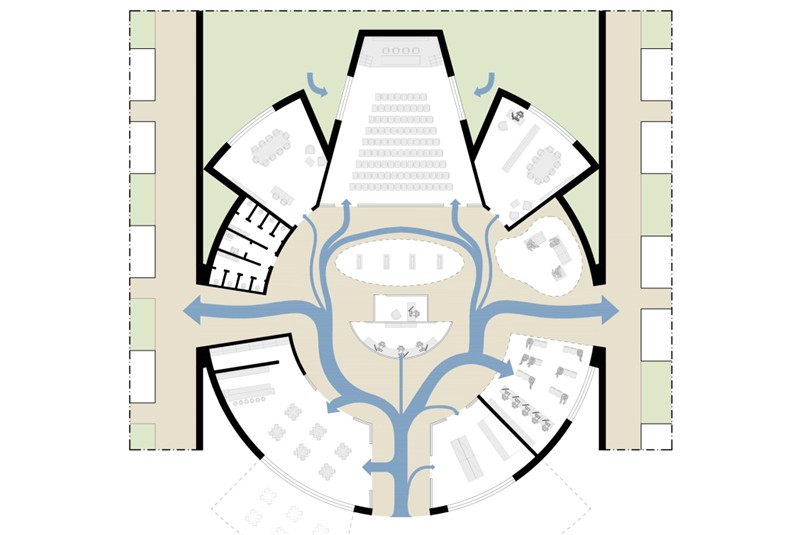

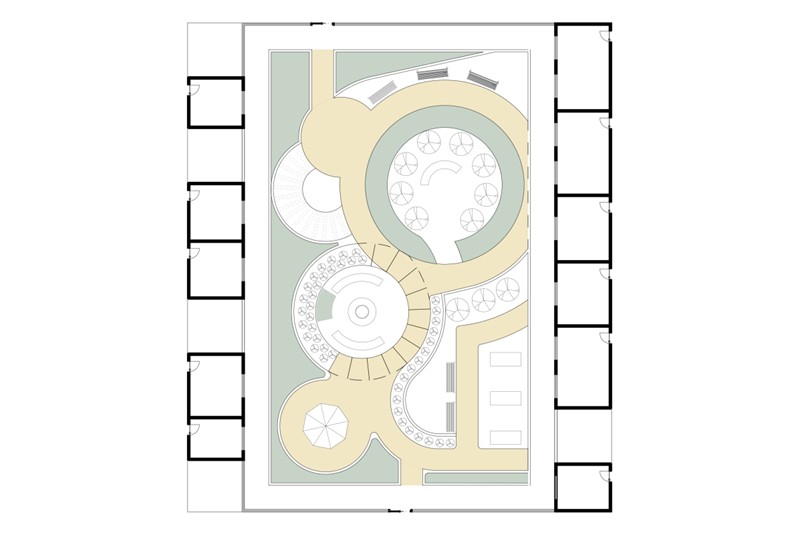

With respect to what we can define as the architectural scale of the

project, the research focuses on the typo-morphological device,

involving both the internal, closed, covered and open-air spaces, and

the external, covered and open-air spaces of proximity. The formal and

constructive potential of an innovative model of a new generation

specialized building is verified and described in terms of distribution

rationality, spatial sequences, access and connection logics,

flexibility of use (not to be resolved with neutrality of shape), of

the figurative characters between internal and external landscape

through the different spatial components, of the identifying semantics,

to which add the necessary design considerations in terms of

construction, environmental and management sustainability for which

reference is made to other already developed skills on the subject ,

obtainable from the general experience of constructing public

buildings, starting with those for schools as well as hospitals. A

process of a compositional nature that involves the dynamic perceptive

dimension of the structure, where for example, with reference to the

psychological analyzes of Ludwig Binswanger (2022), «the own

space and the foreign space are not completely separated from each

other , but they constantly merge into each other through the mediation

of motor skills”, therefore through the experience of a crossing

that is not limited to reaching the desired destination but being able

to grasp the sensations of a sequence capable of narration, of meanings

and if we want emotions.

The approach of the research tends to codify compositional and

generally design behaviors capable of returning an exemplary

prototyping for the orientation use of a Community Health Centre, also

highlighting the importance of those contextual factors and those

cultural variables which, entering into dialectics with a given

typological taxonomy, they will decline the parameters and principles

with a view to a realism of the project to be sought from time to time,

with respect to the different conditions of the places and operating

conditions between new construction and building reuse. An architecture

with a high degree of recognisability and iconic representation within

the urban neighbourhood, a strong point in the strategy of the

regeneration processes of parts of the city.

The typological conception investigated in the research work, through

solutions primarily of relational as well as formal characterization of

the spaces, also makes use of a case study comparison extended to an

international scale where, without prejudice to the different

healthcare systems, elements of interest that can be translated into

the formalization of experimental models (Taheri 2024).

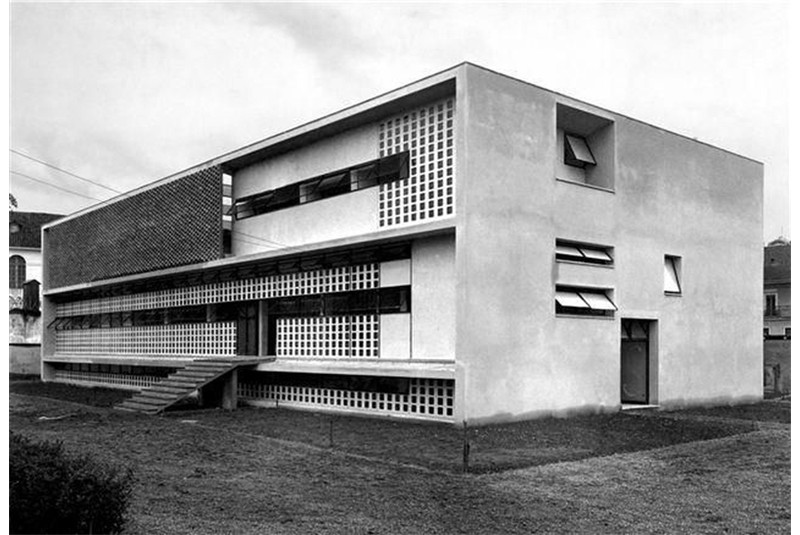

A similar framework of references has not found confirmation in Italy,

where the few recent constructions have failed to define an original

and characterized advancement of architecture intended for this

important public function. We move between the realistic ambition of

certain architecture aimed at spectacularizing and the trivialization

of construction that limits itself to the fundamentals of minimum

living comfort and functional standards (Quintelli 2023b; Simbari

2024). This does not mean that Italian architecture, even in recent

times, has continued to deal with the theme of hospital healthcare,

while the design experience of decentralized healthcare interventions

of which the Ignazio Anti-tuberculosis Dispensary still constitutes an

archetypal reference remains confined to the early twentieth century.

Gardella in Alessandria, an architecture that we could consider

prototypical with respect to the idea of House of Health.

The typological conception of a Community

Health Center first of all addresses the issue of a clear design

of the overall system, through relationships, sequences and logic of

dispositive hierarchy of the formal components corresponding to the

specificity of the environments used from both an operational and

fruition point of view. Precisely, an idea of a unitary spatial device

but corresponding to a complex and therefore necessarily articulated

functionality, rich in potential as well as relational

incompatibilities, to be brought to the maximum degree of organicity

and physiological optimization starting from formal choices.

Here opens the chapter on the components of the device, i.e. the

different environments functionally denoted at the different scales and

use situations, where the research analyzes the characterizing aspects

and hypothesizes spatial configurations of the individual parts also

understood as thematic nuclei in themselves, systems within the system,

in particularly those potentially more susceptible to heterogeneity and

therefore complexity of use.

From this perspective, the entrance and reception space, for example,

has the fundamental task of interpreting a community reality that

combines with the healthcare one, with the need to open the building to

the life of a city that finds itself there not only for care needs but

also with respect to other needs of strong significance, in terms of

aggregation and socio-cultural belonging, which determine the rate of

attractiveness of that environment. It is about characterizing a key

space where information and initial directions can be provided,

distribution to services but also dedicated to meeting opportunities,

free time, the increase of social and health culture through

exhibitions, conferences, training activities, up to traditional

functions of an aggregative nature such as those of a café

rather than a themed commercial establishment.

In certain aspects to be understood as a projection of the reception

space, the waiting space also emerges in this examination, broken down

into the different socio-health services, net of the reduction in times

determined by the IT booking systems. The often underestimated

condition of waiting also lends itself to finding new situational

modalities aimed at the physical and psychological comfort of the

different categories of users (adults, elderly, children, people with

psychological fragility, etc.) through characterizations of the

positioning and shape of spaces designed, as well as colours, images

and furnishing components, according to configurations that go beyond

the usual room with seats or, even worse, the corridor with a row of

chairs at the side. Spaces where the search for characterization of

internal landscapes and internal-external visual feedback, starting

from the light factor, creates environmental conditions capable of

mitigating the feelings of boredom or worry, at variable intensity, of

users in a state of waiting.

An overview of the typological components at play which also involves

the formal characterization of the distribution spaces (corridors,

stairs, elevators); the internal and external green areas near the

building with the resulting effects of light, color and diaphragmatic

visibility, as well as the recreational and curative practicability;

environments with an outpatient function where the duration of daily

operations risks affecting the well-being of medical and nursing staff;

spaces for recreational and group activities of operators capable of

alleviating the psycho-physical stress that healthcare and social

assistance activities often cause; the solutions of a signage which is

responsible for strengthening the identifiable recognition of the

pathways and functional areas. Up to the aspects of an emergency setup

where the ability to adapt and prepare the spaces, both internal and

external to the structure, can respond promptly and functionally

effectively to situations similar to those experienced during the

recent pandemic phase.

The overall organic structure of the Community

Health Centre, to which the complex system of functions and use

situations translated into as many architectural characteristics can be

traced back, is also prepared for further opportunities for functional

complementarity capable of extending the provision of assistance

services. In this case it is a question of integrating hospital

structures responsible in particular for follow-up courses, the

so-called Community Hospitals, to which to add protected residences (in

particular for single women and fragile families) or overnight stay and

assistance structures aimed at homeless people mansion.

It would be enough to fully and prospectively recognize the importance

of the role, the degree of social fruition, the investment in

professional and instrumental resources, to establish the need for an

architecture dedicated to Community

Health Centers as a civil and collective expression that does

not may not take on even an iconic responsibility in the city’s

landscape. However, not so much on the level of a fashionable language

or a figuration of appearance, but rather of the character of a

structure that measures itself and finds its authentic originality in

the relationship with the specificities of the many urban and

territorial contexts of application, that is, where the design process,

while making use of guidance modeling, leads to an outcome resulting

from a detailed dialectic through knowledge of places and cultures. On

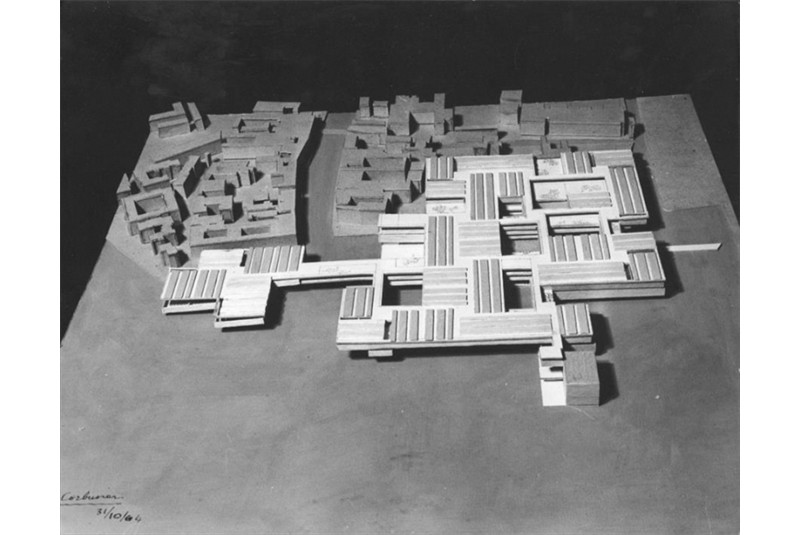

the other hand, what does Le Corbusier’s project for the Venice

hospital of 1963 teach us, according to an ideational relationship

between typological-functional innovation and the character of urban

morphology?9

Notes

1 The Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e

Resilienza (July 2021) provided for 15.6 billion for Mission 6 Health

aimed at “innovation, research and digitalisation of the

NHS” (7.00 billion) and at “proximity networks, structures

and telemedicine for territorial healthcare” (8.63 billion) of

which 2 billion for the community house chapter then revised in 2023

through the reduction of interventions from 1,350 to 936.

2 Adriano Olivetti’s

humanitarianism emerges in all its complexity in the collection La città dell’uomo,

published in 1960 (Edizioni di Comunità, Milan), where in the

writing Il cammino della Comunità he describes the

political-administrative, as well as ideal, potential of the phenomenon

community in the key of territorial decentralization and

solidarity-based provision of public utility services including health

and social services.

3 In the premises, Ministerial Decree

77 prefigures a perspective for the healthcare system that

“enables the country to achieve adequate quality standards of

care, in line with the best European countries and which increasingly

considers the NHS as part of a broader community welfare system with a

one health approach and vision holistic”, in the Gazzetta

Ufficiale dello Stato. dated 22.6.2022, page 9.

4 In relation to primary care, the

European Commission prepared, a couple of years before Covid-19, the

Report of the Expert Panel on effective ways of investing in Health

(EXPH), Tools and Methodologies for

Assessing the Performance of Primary Care, 2018,

https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/expert_panel/docs/opinion_primarycare_performance_en.pdf

5 The PNRR research currently

underway is conducted by the UAL Group – Urban and Architectural

Laboratory of the Department of Engineering and Architecture of the

University of Parma composed of Prof. C. Quintelli (scientific

director), Prof. E. Prandi (scientific co-responsible and coordinator

of PNRR research), Arch. G. Verterame, Arch. A. Simbari, Arch. S.

Taheri.

6 Compared to the Agenas document

referred to in the previous note, from the point of view of

architectural meta-planning, the anticipatory document Health Houses: regional indications for

implementation and functional organisation, approved by

resolution of the Regional Council, appears to be more advanced and of

greater design usability. Emilia Romagna n.291/2010.

7 There is no consideration regarding

the role and architectural quality of the structures built within the

Comparative analysis of primary care in Europe by Agenas, Monitor 2022.

8 Over the last twenty years in

Italy, we have witnessed a process of identity revision tending to

“humanize” the hospital machine through methodological

approaches of Anglo-Saxon derivation based mainly on aspects of a

psycho-emotional or phenomenological nature, for example through

Evidence-Based Design. In this direction, the research for the Ministry

of Health coordinated by Romano Del Nord and Gabrielle Perelli (2012)

is emblematic. More recently, also in reference to the needs of a

multi-ethnic society, see F. De Filippi, G. G. Cocina, (2021), while

the topic of intermediate hospital structures is addressed by Sacchetti

L. and Oberosler C. (2022).

9 As Francesco Tentori observes,

“the French master was the most systematic in his search for the

prevalence of voids over solids and, however, precisely in this project

for Venice, he clearly reverses the course, also taking inspiration

from the Venetian built continuum”. F. Tentori, Learning from Venice, Officina,

Rome 1994, pag. 21..

Bibliography

BINSWANGER L. (2022) – Il problema dello spazio in psicopatologia. Quodlibet, Macerata.