From Local Social Health Units to Community Houses of the PNNR:

again between Ford and Garnier

Sergio Brenna

In conjunction with the elaboration and approval of Law No. 833 on

December 23, 1978 (Establishment of the Italian National Health

Service), commonly known as the Health Reform, I was engaged as a young

research fellow in the research group led by Prof. Guido Canella at the

Faculty of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Milan. The

research focused on investigating the potential impact of the

organization based on the Local Socio-Health Units (USSL) on the

development of hospital and healthcare building typologies. The

establishment of USSL was envisaged by the national framework law,

aiming for a unified approach to the prevention of health conditions.

This approach aimed to bridge the diagnostic gap between the

traditional family doctor and the general or specialized hospital,

focusing primarily on therapeutic functions for established diseases.

As is known, the initial goal of articulating different organizational

levels based on the health, social, and settlement conditions of

various contexts gradually eroded. This erosion began with the

transformation of Local Socio-Health Units into Local Health Companies,

continuing with the conditions imposed by the “historical

expenditure” principle, which transferred the management of the

health organization to the regions. The situation risks worsening with

the proposal of “Differentiated Autonomy,” which finances

regional healthcare based on their own fiscal resources rather than the

service delivery needs. The gap between the so-called “general

practitioner,” a private professional operating “under

agreement” in their private practice, and the bureaucratic

control over the free or semi-free provision of drugs and access to

diagnostic or therapeutic facilities has persisted.

However, I do not intend to anticipate a conclusion here. Instead, I am

interested in reaching an internal analysis of typological and

settlement forms. This is distinct from a political-social and

organizational-administrative debate currently underway, especially

with the proposal to finance the construction of so-called

“Community Houses” through the resources of the PNNR

(Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan). These houses aim to be

a continuous reference point for the population, incorporating

infrastructures such as computer facilities, sampling points, and

polispecialistic instruments. The goal is to ensure the promotion,

prevention of health issues, and patient care by the reference

community.

That remote research activity, modestly funded by the Ministry of

Public Education as part of regular funds and independently of the

specific occasion provided by the coincidence between the

investigation’s subject and the development of institutional

reform, published its results in an issue of the magazine HINTERLAND -

Design and context of architecture for territorial interventions,

vol.

2, No. 9-10, May-August 1979, programmatically titled “Health

Architecture.”

Guido Canella, both the director of the research and the magazine, in

the editorial titled “The hospital between internal history and

external history,” noted how

No other building type

has remained subject, even in the modern era, to intrinsic

preconceptions of functionalist necessity as much as the hospital (...)

There is no doubt that studies on architecture and the city, at least

for fifteen years now, have registered an impulse decisive precisely

from having admitted the necessity and practiced the structural

encroachment towards a more comprehensive external history, to be

understood as reason, natural even before moral, in reducing the

technical, sociological, economic, etc. settings.

It should also be noted, however, in the majority of cases, the lack of

return, not formally analogical but effectively operational, from the

historical excursion to planning; so that this remains abandoned to

itself, cut off from any potentially innovative cognitive enrichment.

(Canella 1978).

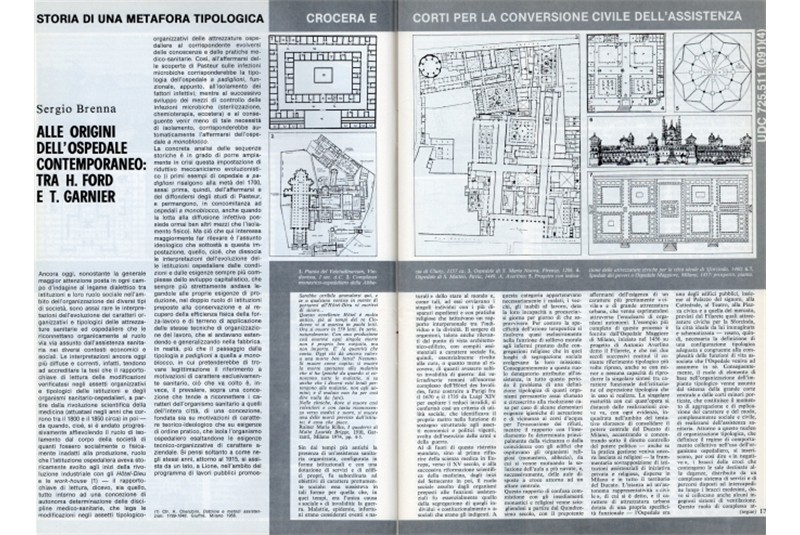

In that magazine issue, I published two contributions resulting from

research on the historical evolution of the relationship between

medical-health knowledge, the social organization of their delivery

forms, and the settlement typologies of the buildings corresponding to

them. One summary outlined the evolution from Roman Valetudinaria to

the 17th-18th century Hotel des Invalides in Paris. It traced the

identification of war as the exclusive “social cause” of

disability and illness to address. This was in contrast to the

compassionate assistance provided by religious organizations, which

remained closely intertwined with the goal of segregating those with

possible epidemic spread. The article also covered the emergence and

spread of the “pavilion” hospital typology in the 17th-18th

centuries. This coincided (and somewhat anticipated) with the birth and

spread of the “etiologically unitary” concept of disease

and cure (“one cause for every disease, one cure for every cause,

one location for each cure”). The pavilion typology deteriorated

into the almost infinitely dispersive arrangement of specialized

pavilions in some German hospitals of the Bismarckian era.

The 20th century saw the emergence and prevalence of the

“monobloc” hospital, where the continuation of

specialization in separate departments found distributive efficiency in

mechanized vertical connections. These connections extended from

underground services to ground-floor reception, specialized therapy and

wards on various floors. This was, however, with the unusual exception

of Le Corbusier’s project for the new Hospital of Venice, where

wards were placed separately on the top floor in a scheme inspired by

the urban organization around “campielli,” derived from the

urban context.

Although I briefly mentioned this chronological-typological overview1,

another full-page article focused on two nearly contemporary examples

representing a strongly dichotomous moment in the opposing concepts of

the relationship between the hospital organism and the urban context.

This contrast influenced the configuration and role of the contemporary

hospital: the Ford Hospital in Detroit (around 1911-1914) and Tony

Garnier’s studies for his idea of the Cité Industrielle

(1901-1904), followed by the subsequent opportunity to implement its

typologies in the Lyon hospital organism (around 1915).

More than the transition from the pavilion typology to the monobloc,

which seeks justification in exclusively health and

distribution-related reasons, what needs to be grasped is the

prevalence of a concept that isolates the hospital organism,

emphasizing its corporate technical-organizational characteristics over

those of a health organization. The latter is articulated to reconnect

various organisms and typologies with the socio-settlement features of

the user population.

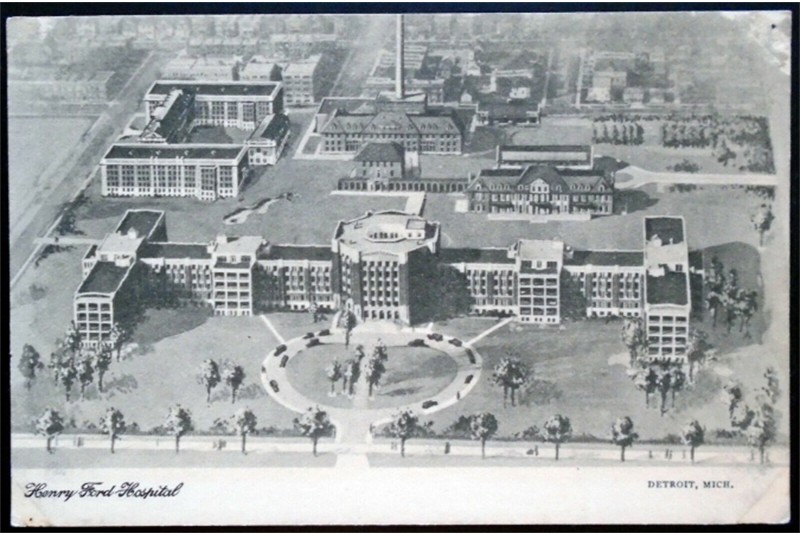

Ford, in fact, acquired the hospital building when it was already under

construction by various philanthropic city organizations. Rather than

participating in philanthropic contributions, Ford preferred to take

direct ownership and management. This way, he could imprint his concept

of corporate organization based on a series of fragmented functions,

somewhat analogous to the work in his factories. Upon arrival at the

hospital, the patient underwent a series of predetermined diagnostic

assessments independent of the specific reason for admission. These

assessments proceeded separately to converge only at the end to

reconstruct the patient’s clinical picture and initiate

specialized therapy.

This choice was primarily motivated by the goal of minimizing, in the

determination of the correct diagnosis and management of therapy-stay,

the influence that individual healthcare operators (doctors or nursing

staff) could have on the organizational structure predetermined by the

factory engineers’ design. This influence pertained to optimizing

the staff/user ratio and reducing routes and spaces.

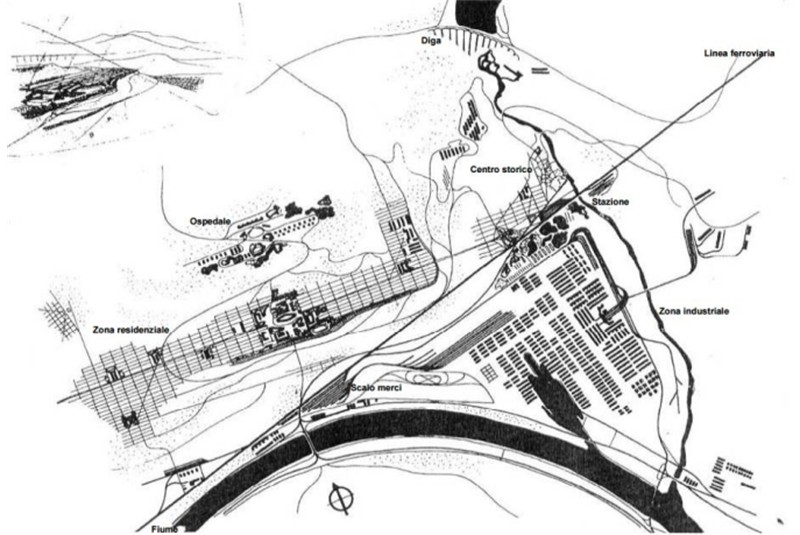

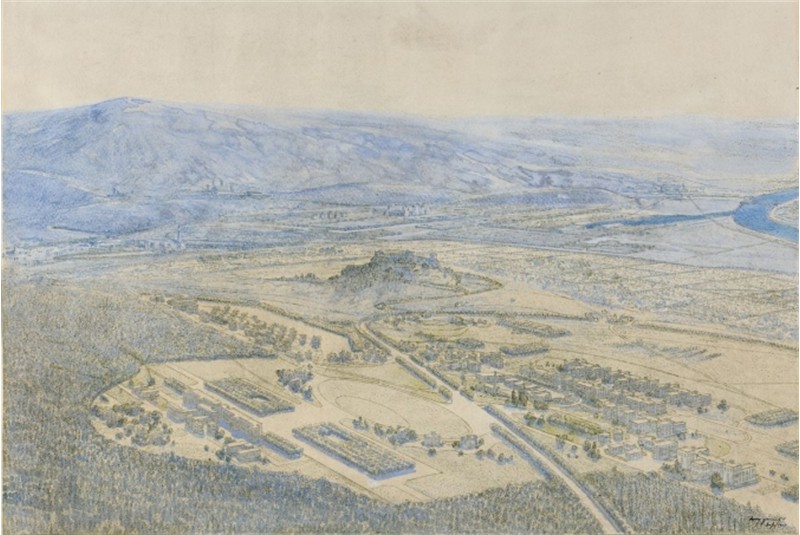

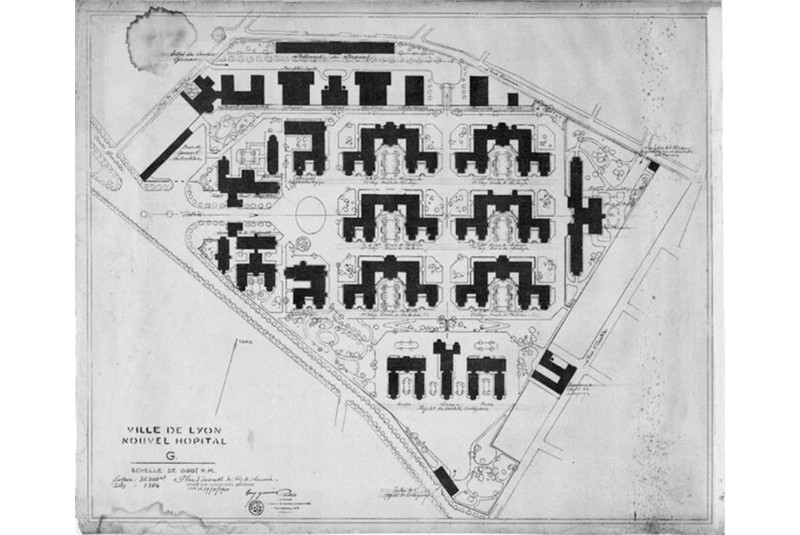

Although Tony Garnier’s hospital typology, initially apparent in

his Cité Industrielle project of 1901-1904 and later in the

concrete realization of the Lyon hospital in 1915, might seem entirely

part of the pavilion hospital at first glance, a closer examination

reveals that his organizational concept of the hospital typology arises

more from being – like other socially oriented facilities and

residential district typologies – a functionally demonstrative

organism of a unitary typological system. This system, albeit diverse,

aims at the overall objective of conceiving a modern “healthy

industrial city.”

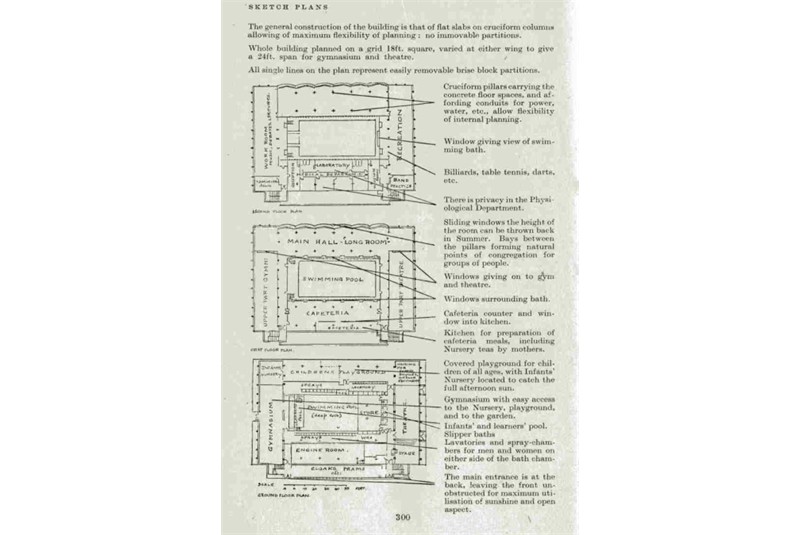

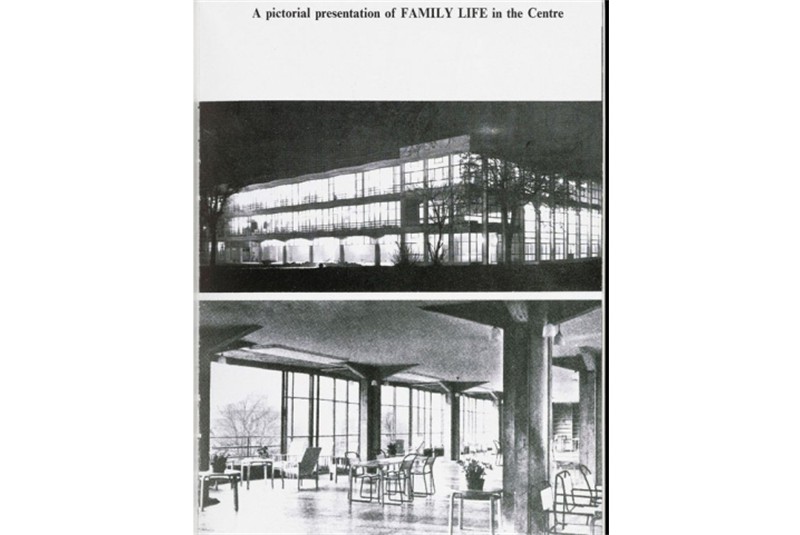

In a way, this vision anticipates initiatives in the United Kingdom,

which, from 1935, experimented with Pioneer Health Centers. Although

this was applied voluntarily to a limited number of families in the

same community, it extended health management to the general living and

working conditions of the user population. This initiative led to a

network of health centers promoting a new generalized role of health

prevention within the community’s associated life activities.

These activities included health functions alongside facilities such as

swimming pools, public baths, nurseries, gyms, restaurants, and

community meeting rooms.

Although interrupted during the war, the experiment was reintroduced in

1947 in connection with the implementation of widespread health reform.

Regarding healthcare structures, it proposed the creation of a vast

network of health centers, especially connected to areas reserved for

social services in new towns. The aim was to overcome both the

Victorian pavilion equipment erected in the 1920s and the more recent

large hospital complexes suffering from gigantism that weighed down

efficiency and functionality due to the congestion of both functions

and the resulting patient load. The goal was to create a new

articulation capable of responding to the ongoing territorial

decentralization needs and the increasing importance of preventive

medicine. However, the limited number of implementations resulting from

the provision of areas reserved for health services as part of social

service facilities did not reveal a more precise typological

characterization. This was in contrast to the prevalence of narrow

hygienic-functional distribution diagrams.

The dichotomy between the proposals of a healthcare organism conceived

as part of the social facilities of the settled community or as the

elective ground of a model of corporate introversion, as evident in

Tony Garnier’s proposals for industrial city facilities and the

example of the Ford Hospital in Detroit, seems to me still paradigmatic

today. It illustrates the differences between the various conceptions

that shaped the origin of the modern hospital. These conceptions are

re-emerging today as relevant in conceptualizing the articulation of

health facilities through a typological organization aimed at providing

an appropriate unifying register of functioning for both basic health

organizations and the associated and collective life functions of the

settled population.

Over the years, hospital organization has continued to be a preferred

application ground for advocates of a managerial technicism that evades

the real problems posed by the need to redefine the organization and

typology of health organizations on new bases of compliance between

socio-settlement conditions and health facilities. This is done to

achieve a higher degree of coherence and innovation in health

facilities in relation to public general service spaces.

The opportunity offered today by PNNR funding for the construction of

so-called “Community Houses” should be seen again as the

possibility of returning to pursue the goal of articulating health

facilities into differentiated organisms. These organisms are based on

health, social, and settlement conditions of various contexts, starting

from the need to rethink the vision within the integrated endowment

spaces of public services for settled communities.

From a typological perspective, this requires the ability to develop

solutions in which Community Houses can disaggregate the current

autarchic compactness that has developed within hospital corporatism.

Instead, they should promote the reintegration of basic health

activities around the social and collective moments, both internal and

external to the health function. Moreover, it requires a reaffirmation

of the goal of public and collective design in the configuration of

facilities and public spaces. This is in contrast to the prevailing

concept of “urban regeneration,” which is almost entirely

delegated to proposals from private real estate developers in a sort of

“competition tender” of ideas and solutions inevitably

subject to their inherent playful-consumeristic vision.

Bibliografia

CANELLA G. (1979) – “L’ospedale tra storia interna e

storia esterna” In Hinterland, Architettura della salute n. 9-10.

BRENNA S. (1979) – “Storia di una metafora tipologica. Alle

origini dell’ospedale contemporaneo: tra H. Ford e T.

Garnier”, in Hinterland n. 9-10, pagg. 16-29.

GARNIER T. (1932) – Une

cité industrielle: étude pour la construction des villes.

C. Massin & Cie, Paris

MARIANI R. (a cura di) (1969) – Tony

Garnier. Une Cite Industrielle, Jaca Book