FA(little)Magazine and the “little magazines” of twentieth century architecture

Lamberto Amistadi, Enrico Prandi

A few days ago arrived

Nicola Di Battista’s reflection on the role and function of printed

architecture magazines in the context of the change in direction of Domus, to which retorted a Michele de

Lucchi who lent himself, along with Carlo Cracco and Lapo Elkann, to pose for

the cover of «AD - Architectural

Digest» (December 2017) in a new joint project

designed by the same scion of the Agnelli family – Garage Italia – which transformed a post-war AGIP service station

designed by Mario Bacciocchi in Milan’s Piazzale Accursio into an Italian-style

hub: with food, cars, and design.

Battista argued

that «a magazine must certainly be able to see

and know the projects, products, and thoughts that our time produces but, above

all, to tell the stories that make them possible, the stories that underlie

them.»[1]

That is what we have tried to do in this inaugural issue of «FAMagazine», which is not

inaugurating the magazine – already born back in the distant 2010 – but its new

graphics and Open Journal Systems platform, together with a new web address www.famagazine.it.

The story we wished

to tell in this Issue 43, is that of certain Italian and US architecture

magazines that determined the architectural debate in the final quarter of the

last century, and the story of the transition from the world of magazines on

paper to the digital ones, «FAMagazine» included.

The decision to

open this new season of «FAMagazine»

with an issue on architecture magazines is in itself an

explicitly self-analytical reference. Among these are many “little magazines”

so that, if initially the epithet was attributable mainly to the format and to

a limited circuit of influence, which were often the outcome of independent,

niche, or non-commercial publishing, with the passing of time it has ended up

denoting some characteristics that make these magazines particularly

interesting for architectural research as an impulse to experiment, the leaning

(or better, the bias) of the editorial board in directing the thinking, and in

the desire to plough new research roads, give voice to new, less common, and

avant-garde disciplinary languages. A sort of experimental laboratory of ideas.

The Little Magazine

phenomenon, born in the 1920s in the context of the American literary current

and much explored in the United States, especially after the Second World War,

ended up intruding in a disciplinary sense – as often happens among the

different arts – and affecting architecture, so that, as we were reminded by

Claudio D'Amato, at the Little Magazines

Conference: After Modern Architecture, 3-5 February 1977 organized by the

IAUS New York, it was joined by many of the protagonists of the architectural

debate who at that moment were proposing to relaunch deliberation on

architecture, theory and criticism through the tool of the magazine: «Architese» (Bruno Reichlin,

Stanislaus Von Moos), «Arquitectura Bis» (Oriol Bohigas, Federico Correa, Rafael Moneo), «AMC-Architecture Mouvement Continuité» (Jacques Lucan, Patrice Noviant), «Controspazio» (Alessandro

Anselmi, Claudio D’Amato), «Lotus» (Pierluigi Nicolin, Joseph Rykwert) and many other interested

parties starting from the organizer himself, Peter Eisenman, and friends of New

York’s Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies such as Edith Girard, Mario

Gandelsonas, Anthony Vidler, Stanford Anderson, Livio Dimitriu, Alessandra

Latour, Lluis Domenech, Peter Blake, Kenneth Frampton, Robert Gutman, Colin

Rowe, George Baird, Peter Marangoni, Diana Agrest, and Suzanne Frank.

Authentic “Little

Magazines” in architecture were the avant-garde ones of the 1920s which

attracted ideological currents and their groups of promulgators, when not born

specifically as a tool to disseminate their values: «G» (1923-26) and «Bauhaus» (1928-1933) in

Germany, «Sovremennaia

Arkhitektura» (1926-30), «Lef» (1923-25) and «Veshch» (1922) in Russia, Wendingen» (1918-1931) and «De Stijl» (1917-31) in the Netherlands, «L’Esprit Nouveau» (1920-25) in

France, and all the Futurist magazines in Italy such as «Valori plastici» (1918-21), «Lacerba» (1913-15), and «Noi» (1917-20 and

1923-25).

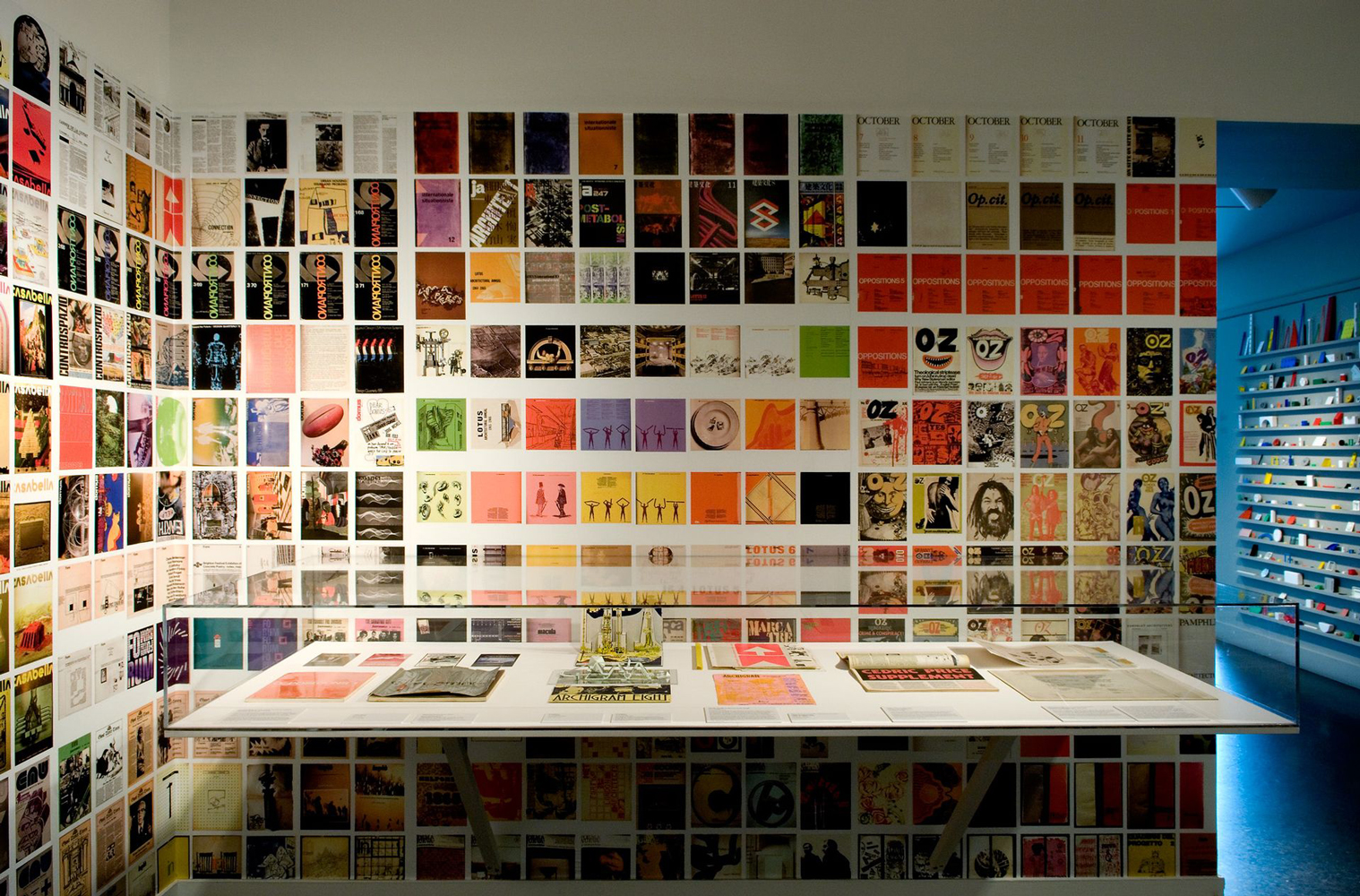

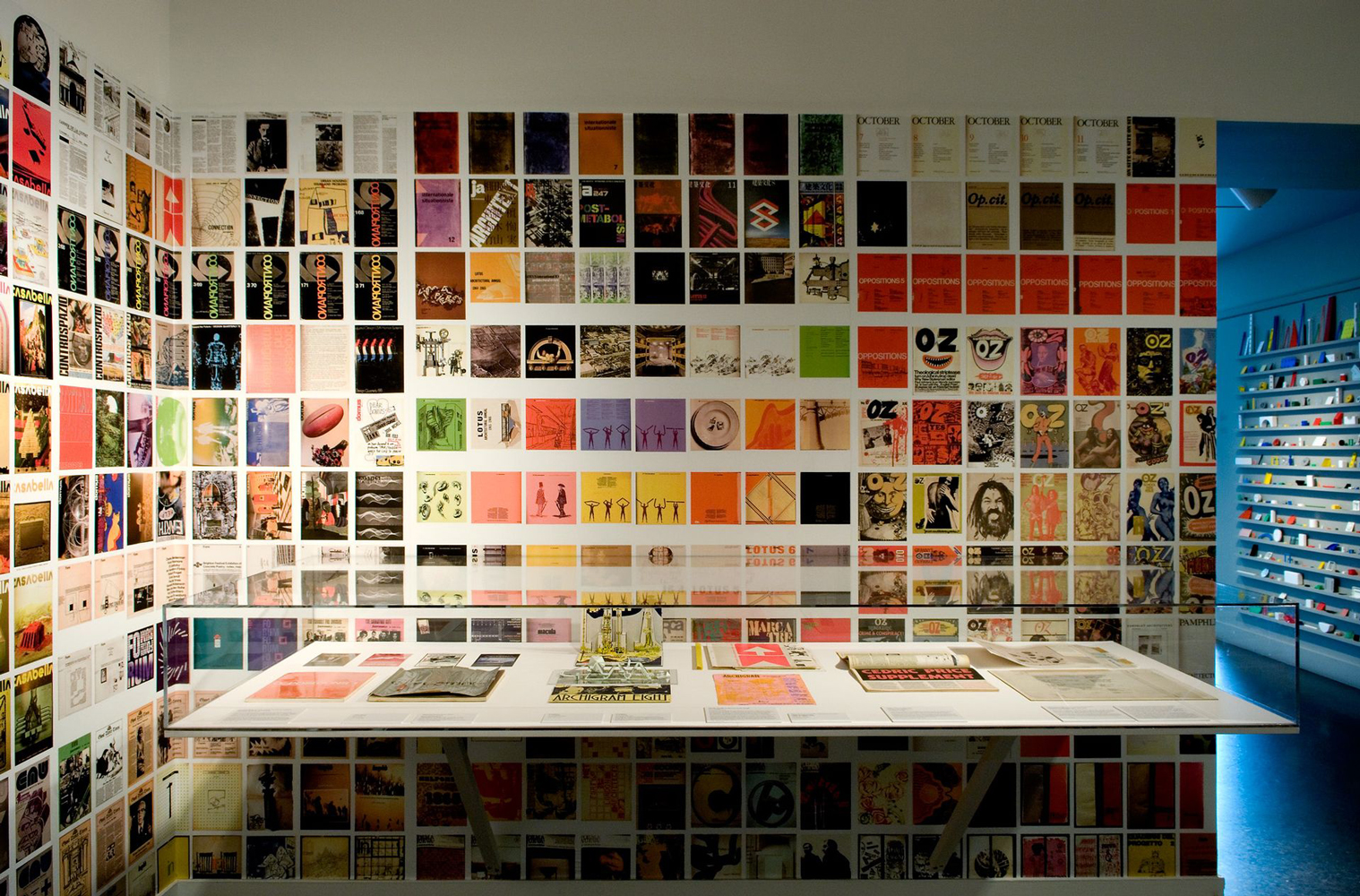

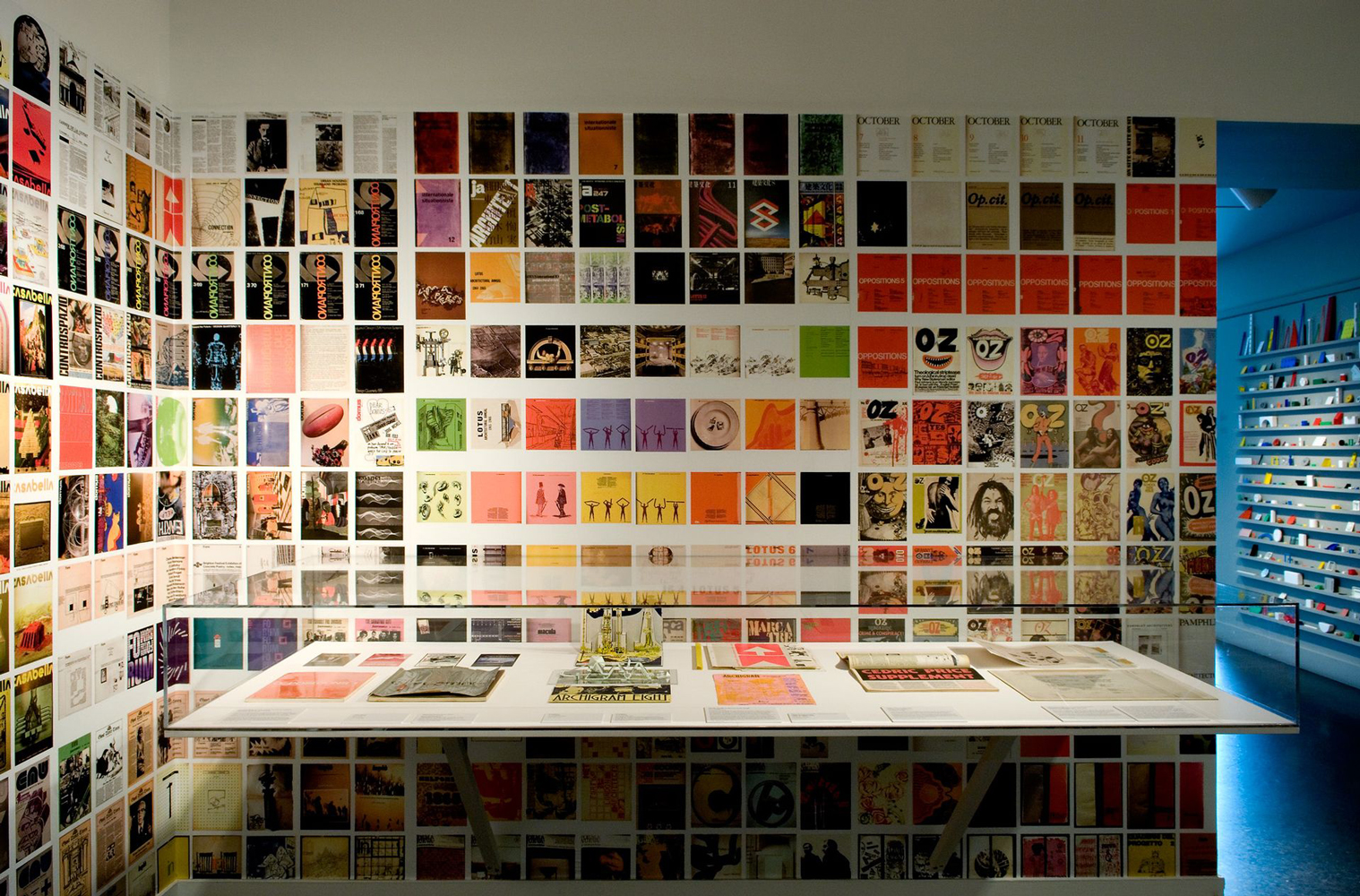

An analogous

phenomenon was seen in the second half of the twentieth century when the

historical conditions enabled a return not so much of the historical

avant-garde, as an attitude of breakage, the neo-avant-garde, of course, which,

between the Sixties and Seventies, produced the phenomenon of the second season

of Little Magazines, with an exhibition organized at the Canadian Center of

Architecture by Beatriz Colomina and Craig Buckley entitled Clip/Stamp/Fold 2: The Radical Architecture

of Little Magazines 196X-197X.[2]

It is

interesting to note that the characteristic of the second season of the Little

Magazines in architecture was that they emerged from inside the Schools of

Architecture, where it was the students, rather than the teachers of the first

season (suffice to think of Le Corbusier and «L'Esprit Nouveau») who

represented the voice of cultural change. It is no coincidence therefore that «Perspecta» was a student

magazine and that «Casabella» published, in that same period, the Florentine radicals who, still

at their school desks, launched their offensive on conservatism, rather than

the youngsters of the AA School, Rem Koolhaas, Zenghelis, Hadid, or Archigram.[3]

This phenomenon

did not pass unnoticed by the intelligentsia of architecture of the period, who

between 1966 and 1972 came out with articles on the topic by historians and

critics, noting that also magazines which could not properly be defined as “little”

had at that time gone through a “little” spell (as in the case of «Casabella» and «Architectural Design»)[4].

Among these, Denise Scott Brown in the «Journal of the American Institute of Planners» in 1968[5],

Peter Eisenman in «Architectural Forum» in 1969 and in «Casabella» in 1970[6],

Chris Holmes in «Architectural Design» in 1972[7],

while Reyner Banham in «AAQ-Architectural

Association Quarterly», commended the

student zines, and Robin Middleton towards the end of his direction inaugurated

the “little magazine” period of «Architectural

Design».[8]

The reason for

the interest in little magazines was to be found in the climate of great

cultural vivacity that was establishing itself in the worlds of art and

architecture: Denise Scott Brown, in her Little

Magazines in Architecture and Urbanism, wrote that «little magazines [...] provide good guidance with regard to new

trends in the profession and are an indicator of what we can expect in

subsequent years.»[9] While Banham highlights that in those years rather than constructed

buildings it was the projects published in some [little] magazines that marked

architectural theory. In his opinion, these magazines, through the projects,

were able to report a thinking about architecture that was constantly updated,

unlike the buildings which rose already obsolete.[10]

That this was a period of great cultural change is indisputable as is the fact

that the cultural climate and fervour managed to seduce even notoriously

orthodox historians and critics.

The Little

Magazines were the protagonists of a little revolution.

Starting off from this point of view, the best magazines could not

help playing a polemical role, tried to keep their guard up and block the

lethal blows that the world of profit and quantitative logic craved to throw,

not so much against them – of no interest to them – but against architecture;

which was able to respond with a few well-aimed salvoes of its own made up of

good ideas that sometimes even succeeded in exerting a beneficial influence on

that same world.

Not without some forcing, we have gathered some of these magazines –

«Zodiac», «Perspecta», «Controspazio», «Lotus», «Casabella», «Phalaris», «Oppositions» – under the common

label of “little magazines” not just because they are directly attributable to

the concept of the avant-garde or were all born within student movements – but

for the courage, freshness and even unscrupulousness with which they advanced a

speech on architecture that to them was coherent, more or less complacently

franked by the logic of profit, while gathering around themselves affectionate

communities of young architects, scholars, and readers.

Even if the relations of these magazines with the avant-garde and

history, continuity and discontinuity, was quite different, especially between

Italy and overseas, their degree of kinship, their entanglements and borrowings

were so unexpectedly numerous that instead of foundations, we should speak of

re-foundations and continuous re-emergences of points of view, themes, and

architecture magazines. To the point that, in some moments, it seems to us that

all of them belonged to a single great collective cultural adventure, one that

encompassed authors, editors and – for Bataille, at least – the only possible

community, that of readers.

Guido Zuliani tells us of Peter Eisenman’s passion for the “little

magazines” of the European avant-garde – «De Stijl», «Mecano», «L'Esprit Nouveau», the «Casabella» of Pagano, Moretti’s

«Spazio» – or his debt to British magazines of the ’60s such as «Architectural Design» and «Architectural Review» or the

double number 359-360 of «Casabella», whose publication of the work of the Institute of Architecture and

Urban Studies under the title of “The City as Artifact” anticipated the birth

of «Oppositions». And of how the origin of the birth of «Oppositions» harboured a certain

intolerance of a world of journalism that was rather intractable to ideas and somewhat

subservient to commercial practice.

Not very different were the motivations from which arose «Perspecta», nor was its debt to Italy any less. «The first reason», wrote

Norman Carver, one of the editors of the first number, «was our frustration due to the lack of exciting projects and the

fatal absence of content that characterized the commercial architecture

magazines of that time.» While «Perspecta» owed a debt to Italy

for its historical-critical tradition while, more directly, its most famous

issue – the no. 9-10, characterized by the well-known White/Gray debate – was

inspired by Issue 281 of Rogers’ «Casabella

Continuità» entitled “Architettura

USA”.

This ratio of continuous exchange, of quid pro quo between

America and Europe, is also the theme as well as the title of Issue 13 of «Phalaris», “the architecture newspaper” – as it styled itself – directed by

Luciano Semerani between 1988 and 1992. Semerani wrote in his editorial: «They come and go across and over the Atlantic from Europe to America

and from America to Europe, flocks of migratory ideas, perhaps always the same

ideas, but each time they return from a trip they have changed because they are

not eternal ideas, or perhaps they are tracks, routes, and points of departure

and arrival that are always identical, but the journey and the travel time, by

themselves, will change them; in appearance at least.» And he published projects by Frank Gehry, John Hejduk, Steven Holl,

plus an extraordinary article on the Elvis Presley myth.

Even Claudio D'Amato re-evoked the “little magazine” image to define

the form of these journals of research, theory, and criticism, “produced

outside the great editorial circuits” and advanced almost exclusively by

university lecturers. «Controspazio» too, like «Perspecta», was born within the political passion of a student movement, and

like «Perspecta», was the vivid reaction to a feeling of powerlessness in the face

of the massacre that professional practice and urban speculation were

inflicting on the suburbs of Italian cities. The polemical vein of «Controspazio» – directed

by Paolo Portoghesi from 1961 to 1981 – was however already included in that “contra”

accompanying the Italian term for “space”, which recalls another affiliation

(or counter-affiliation), the one with the magazine «Spazio» directed by Luigi

Moretti.

A blood relation of «Phalaris» and «Controspazio» – as Enrico Bordogna defined it – «Zodiac» also ranks among the

research journals. In this case, the bond with America and New York is

inscribed in the graphics of Massimo Vignelli. «Zodiac» too was a “re-emergent”

magazine, or the fruit of a re-foundation, whose roots lay deep inside the

Italian cultural tradition, starting from the Comunità publishing house of

Adriano Olivetti and their first series of «Zodiac». This link with

Olivetti was stated explicitly in the 1988 colophon which reads as follows: “New

series. International architecture magazine founded in 1957 by Adriano Olivetti.”.

The Steering Committee too was the expression of a “trend” and a “continuity”,

boasting figures like Carlo Aymonino, Ignazio Gardella, Aldo Rossi, Gianugo

Polesello, Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co and foreigners of the calibre

of Richard Meier, Rafael Moneo, James Stirling, and Kurt W. Forster.

Some phases of «Casabella» can also be ascribed to this tradition of research journals, or at

least to some of those preceding the rather bombastic dimension of the time.

The «Casabella» that Gregotti directed between 1982 and 1996, for example, insisted

on a radical programme, according to which the transformation of the city and

territory should involve architects, planners, and engineers in a complex,

integrated, multidisciplinary process. The magazine also sought to open a

debate involving the world of professionals and lead them hand in hand towards

a good practice of architecture. The important thematic section dedicated to

building innovation and sponsors is indicative in this sense, just as there is a

significant difference between the concepts of “city as artifact” of Alessandro

Mendini's «Casabella», and that of the “architecture of modification” of Vittorio

Gregotti’s «Casabella».

Lastly, «Lotus» was of another kind

still, designed as it was in 1963 by a car racing fan – Bruno Alfieri – as a

yearbook of architecture. Starting from Issue 3 it too became an international

magazine of critical investigation and its Issue 7 on “Architecture in the formation

of the modern city” went down in history.

«FAMagazine» is not really a trendy magazine (perhaps we are not snobbish

enough!). Without a doubt – as described even more clearly in the new blue

masthead designed by Carlo Gandolfi – it is a magazine of research, on

architecture and the city.

In terms of approach, its editorial staff is very much akin to those

strange communities of gold miners narrated in National Geographic

documentaries: whole communities who, with the help of ingenious and sometimes

unlikely machinery, dredged tons upon tons of water and sand in those endless

rivers of the Yukon in search of a few grams of gold. What comes out are issues

and themes that are unexpectedly but unquestionably interesting, some more à la page, others extraordinarily demodé. In the period 2010-2013, «FAMagazine» published articles

on/by figures of international architecture such as Asplund, Lewerentz, Mart

Stam, Mendes da Rocha, Artigas, and Bogdanovic, and Italians such as Rogers,

Samonà, Muratori, Quaroni, Aymonino, Semerani, Isola and Polesello. Schools of

Architecture in Italy and Europe, the Brazilian “Paulista School” and some of

its members, the relationship between architecture and crises, accounts of

events like the 2010 Venice Biennale and the 2012 Biennial of Public Space in

Rome, problems relating to the condition of the contemporary city, from the

experiences of the INA-Casa neighbourhoods to today's regeneration processes

for historical cities (from densification to the valorizing of empty urban spaces)

and the suburbs (the case of Tor Bella Monaca). In addition, more specific

issues such as the restoration of the Modern, and the role of ruins in an

architectural project. It has addressed topical theoretical issues in the

disciplinary debate such as the role of morphology or infrastructures in the

processes of transforming the land, and the theme of Designing the Built,

applied to Italian and German cases (Bauen

im Bestand).

Starting from 2014, the issues became strictly thematic and the

output quarterly. The titles are self-explanatory: The Spectacularization of Dismission no. 42, Report on the State of the Former Psychiatric Hospitals in Italy

no. 41, Amnesty for the Existing no.

40, Law and Heart. Analogy and

Composition in the Construction of Architectural Language no. 39, 2017; Architectural Pedagogies. Worldviews no. 38, Building and/is Building Ourselves. The complex relationship between

architecture and education no. 37, Character

and Identity of the Work no. 36, Madrid

Reconsidered no. 35, for 2016; University

Campus and City no. 34, Smart Design

for a Smart City no. 33, The Orderly

City. Dispositio and Forma Urbis no. 32 Epiphenomena, no. 31, 2015; Six Italian PhD Research Works on

Architectural and Urban Design no. 30, 2004-2014

Ten Years of the Festival of Architecture no. 29, Impossible Research. Imagination in the Architectural Project.

no. 27-28, Intensive Teaching for the

Project No 8. 26, Oscar Niemeyer: Architecture,

City no. 25, for 2014.

But even in the

digital field, not all that glitters is gold.

Since

undertaking an online magazine today – certainly less burdensome and costly

than a printed one – is fairly simple (just a web address, a director enrolled

in the order of journalists, and an ISSN), we are seeing a certain quantity of

active magazines that is not less than those dormant or decommissioned ones

within much shorter time-spans than in the past. Without speaking of the

confusion generated by hybrid forms including simple websites, blogs, e-zines,

and everything else in between, as demonstration of an attitude, that of

architecture magazines, which is extremely variable though undermined on the

one hand by a persistent and chronic lack of investment in scientific

publishing (and more in general in research and in its instruments of

dissemination) and on the other by the clumsy attempt of the ministerial bodies

to regulate everything. Hence the basic misunderstanding of transferring the

value of the container (magazine) to the content (single item) in qualitative

evaluations.

We, who have

always believed in this form of communication in architecture and its critical

thinking, are preparing for a substantial revamp. In the Manifesto founding the

magazine (which we invite you to read) we compared the magazine to a “free (and

welcoming) space” for the comparison of different stances. Well this area,

today, has a new guise. Since “you can’t judge a book by its cover”, the

adoption of an international platform specifically designed for scientific

journals allows many advantages: from workflow management (the steps that

accompany an article from when it reaches the editors to the time of its

publication are many and complex) to the final look, and the safeguarding of

the archive with the relentless tracking of addresses and a guarantee of

perennial consultation. If libraries were once the guarantee of preserving

their valuable content of disciplinary knowledge over time (the famous public

granaries to amass reserves against the winter of the spirit within Yourcenar’s

meaning), today much of that “grain” travels in an immaterial inconsistency

through the ether, in that World Wide Web which represents our greatest

opportunity. If the task of «FAMagazine», referring once again to the Manifesto, is also that of a “mnemonic

device to remember”, it is necessary that the memory is kept alive constantly,

without any risk of “memory loss”.

If Victor Hugo

saw a great danger for architecture in Gutenberg's revolution – the invention

of the printing press and books as the killer of architecture, what might he

write today in the face of this further revolution that sees on one side

printed paper giving way to that far more volatile digital paper, and on the

other those contemporary stone monuments (far less often in stone, and fewer

and fewer monuments in Rossi’s sense of the term) witnesses of phenomena that

are no longer secular but as short and transient as they are precarious? “In

the form of printing, thought is more imperishable than ever; it is volatile,

elusive, indestructible. It blends with the air. In the time of architecture,

it became a mountain and took forceful possession of an age and a space. Now it

becomes a flock of birds, scatters to the four winds and simultaneously

occupies every point of air and space.'[11]

Hugo’s metaphor of printed thought is now paying the price of a further

revolution, the digital, one of whose greatest merits is the widespread

dissemination of information, but among whose greatest defects is the

multiplication of this so that it does not always readily make the information

sought available, with the result that we rely on the most popularized,

superficial information (waiting for the Big Data managers to invent agile

information management systems).

Let us now turn

to what lies behind the renewed guise of «FAMagazine». As always, a moment

of transition is the occasion for a stocktake, in our case limited to the

period 2014-2017: 4 years, 17 issues, 116 articles, (to be added to the previous

3 and a half years and a further 122 articles). If it is true that the numbers

are not important (in an era in which even quality is reduced to a number, as

demonstrated by the logic of the National Agency for the Evaluation of

University and Research – ANVUR) it is the contents that offer the scientific

community a valid tool to critically evaluate the work of our magazine.

Perhaps it is

useful to summarize our story. The “Magazine of the Festival of Architecture”

was born in September 2010: at that time ANVUR carried out its first VQR (in

which FAMagazine did not appear among

the list of scientific journals). In 2012, in the first suitable timeslot to apply

for recognition, we explained our reasons, and in 2013 we received scientific

recognition. In the same judgement,

excusatio non petita, accusatio manifesta, ANVUR responded that initially «FAMagazine» was not deemed to be

scientific but merely an informative newsletter. Glossing over this, by

2014-15, with ANVUR regulations in hand, we discovered that we possessed a

score well beyond the threshold required to be in Class A.[12]

We awaited a

suitable timeslot to present our second petition for recognition (this time for

Class A) and just shortly before, thanks also to the debate on anomalies in the

lists of scientific journals for those non-bibliometric areas, a new regulation

was issued (Regulation for the classification of magazines in the

non-bibliometric areas – Criteria to classify magazines for the purposes of

national scientific accreditation) which tightened the screw to such a point

that it cast doubt on the legitimacy of most of the journals already contained

in the lists. As the saying goes, “closing the stable door after the horse has

bolted”.

Following the

lively debate from those who had not seen the access door to Class A

considerably restricted (especially when inside there were magazines that did

not meet the criteria, or were no longer published, and so forth), ANVUR

decided to caution the directors of scientific journals with the announcement

of periodic checks on the requirements, and if unjustified, the revocation of

the description “scientific” or of the magazine's Class A status. Thus, indications

on the frequency when a particular magazine was considered “scientific” began

to appear in the final version of the list of scientific journals currently

available.

We look forward

to the next timeslot to make a formal application for Class A recognition, and

in the meantime, we are continuing to “dredge” and accumulate numbers and

themes thanks chiefly to a vast community of enthusiastic scholars, mostly

young and extremely knowledgeable, and a no less extensive international

community of readers. Whom we thank.