Fig.

1 - Athens Metro, Acropolis Station. Photo by Author.

Fig.

2 - Sofia Metro. Arrangement of the findings of the Roman city. Photo

by Author.

Fig.

3 - Rome Metro, excavations of line B at Termini; domus

found they will be demolished and the frescoes removed. Archive

Photographic Archaeological Superintendence of Rome.

Fig.

4 - Naples Metro, Municipio Station, rendering of the

arrangement of archaeological finds according to the Siza-Souto de

Moura project.

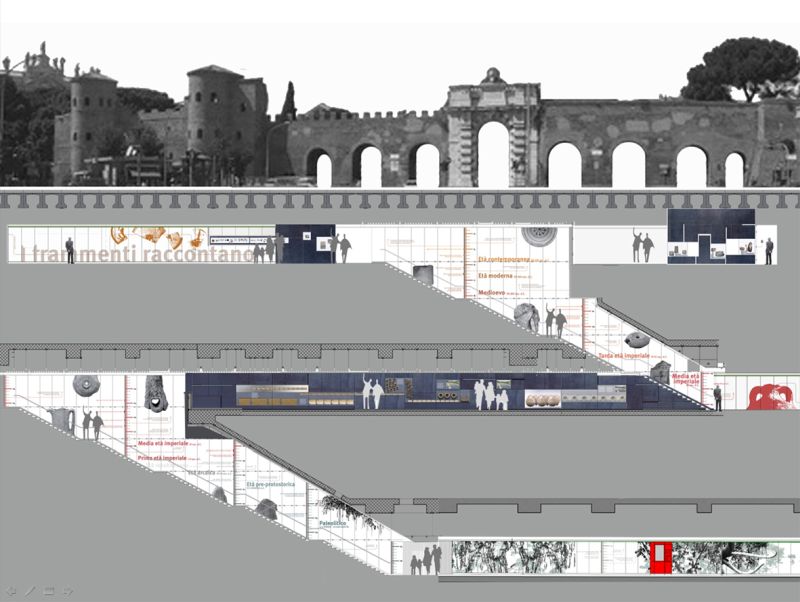

Fig.

5 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

Conceptual section of the story of the stratification.

Fig.

6 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

Atrium set up.

Fig.

7 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

Preparation of archaeological finds.

Fig.

8 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

The narration becomes preparation.

Fig.

9 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

The stratimeter and the story in images.

Fig.

10 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

Installation of the hydraulic works of the imperial agefound by

excavations at the depth corresponding to the

plan.

Fig.

11 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

Crowd of passengers and onlookers; daily life of the heritage.

Fig.

12 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

An unexpected encounter with archeology.

Fig.

13 - Author & C. Rome Metro, Line C, San Giovanni Station.

A degree of attention and interest for each of the passengers.