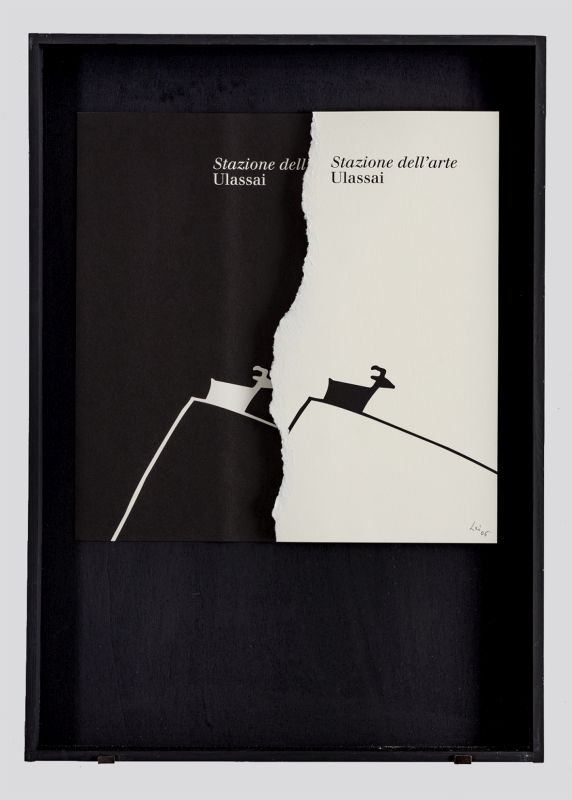

Fig.

1 - Maria Lai, Stazione dell'Arte, 2006, collage di serigrafie,

Plexiglass 70x50 cm. Ph. Tiziano Canu. Courtesy Fondazione Stazione

dell'Arte

Fig.

2 - The abandoned Jerzu station. © Salvatore Sechi

Fig.

3 - The Art Station in its relationship with the valley and the

landscape of Ogliastra. © Sergio Aruanno

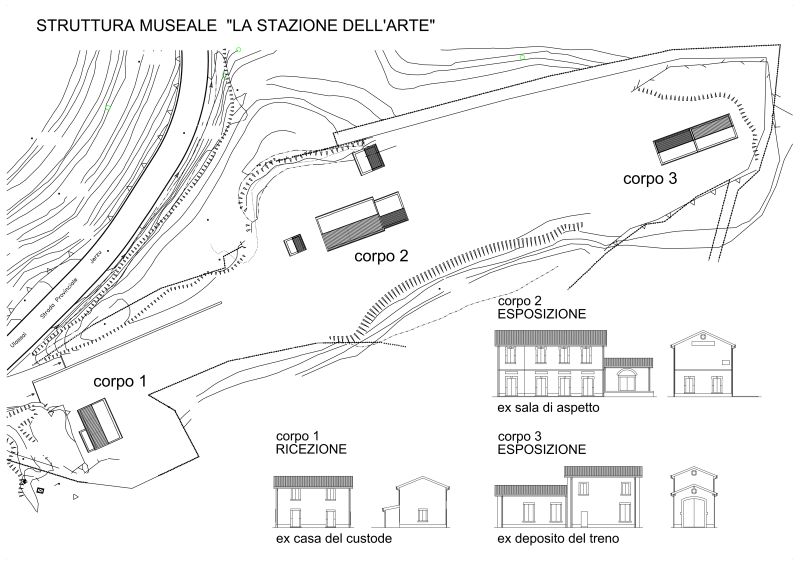

Fig.

4 - General plan. Project by Sergio Aruanno, Nazario Fusco,

Luigi Corgiolu, Demetrio Artizzu

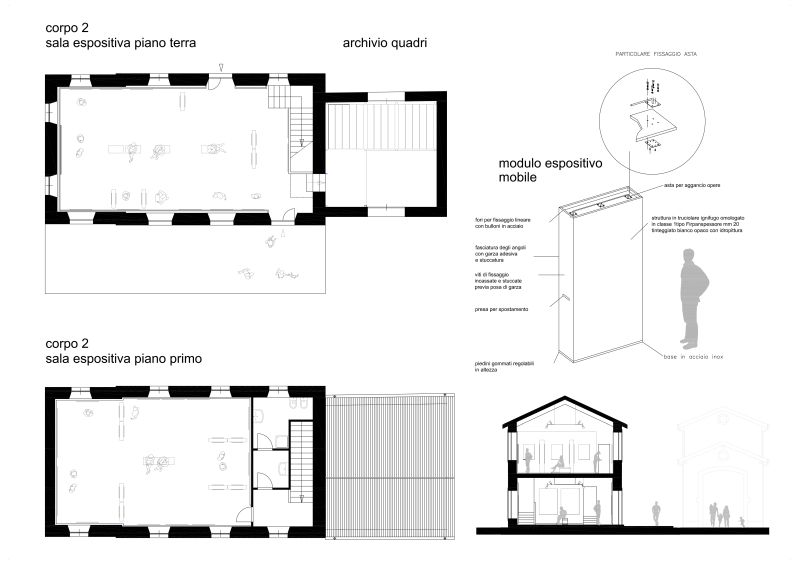

Fig.

5 - Building 2 (former passenger building): exhibition rooms-deposit of

paintings. Project by Sergio Aruanno, Nazario Fusco, Luigi

Corgiolu, Demetrio Artizzu

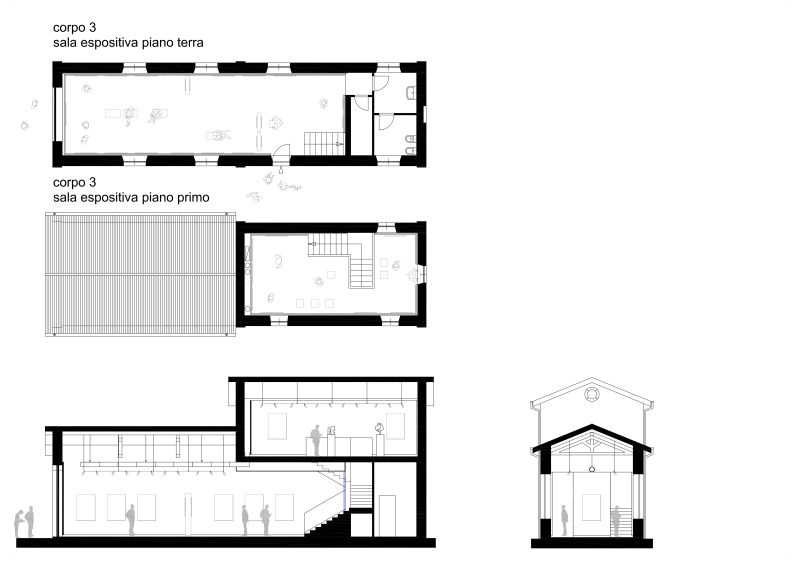

Fig.

6 - Building 3 (ex train depot): exhibition halls. Project by Sergio

Aruanno, Nazario Fusco, Luigi Corgiolu, Demetrio Artizzu

Fig.

7 - Building 2, exhibition room on the ground floor. View of the installation of Maria

Lai. Sguardo Opera Pensiero. Ph. Tiziano Canu. Courtesy Fondazione

Stazione dell'Arte

Fig.

8 - Building 2, exhibition hall on the first floor. View of the installation of Maria

Lai. Sguardo Opera Pensiero. Ph. Tiziano Canu. Courtesy Fondazione

Stazione dell'Arte

Fig.

9 - Il lavatoio, internal, 1982-1989. Archive Ilisso - Courtesy

Archivio Maria Lai

Fig.

10 - Maria Lai, La scarpata. Archive Ilisso - Courtesy Archivio Maria

Lai.