Fig.

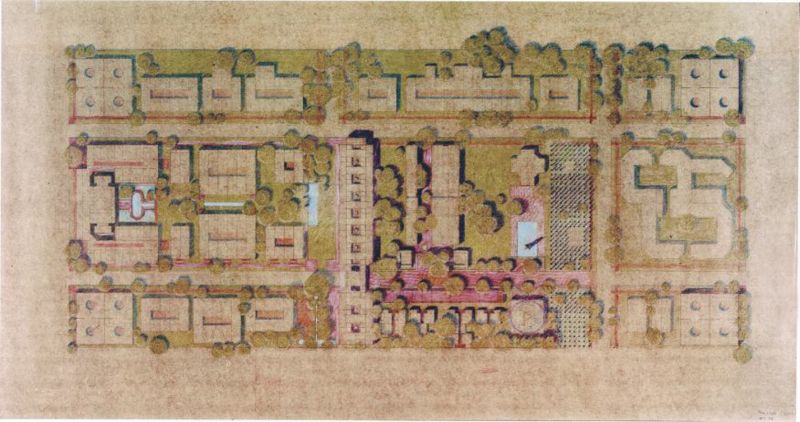

1 - Louis I. Kahn. Planimetria del De Menil Museum e intorno urbano,

Houston, Texas. Fonte: P. Cummings Loud, Louis I. Kahn. I musei,

Electa, Milano 1991.

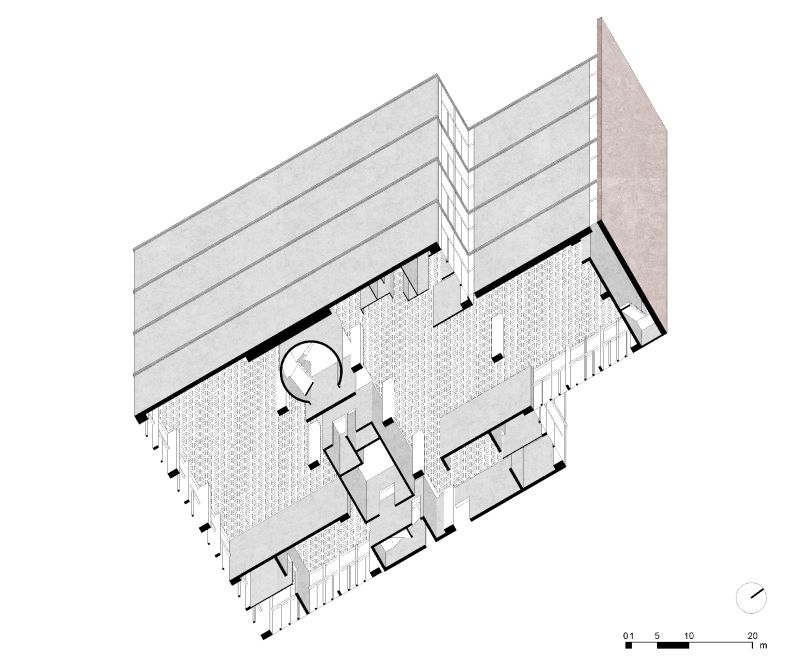

Fig.

2 - Louis I. Kahn. Yale University Art Gallery. Assonometria. Disegno di Roberta Esposito.

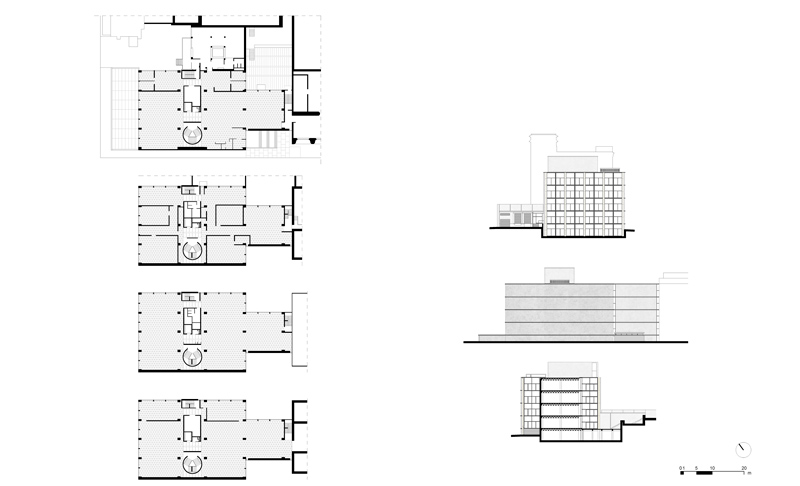

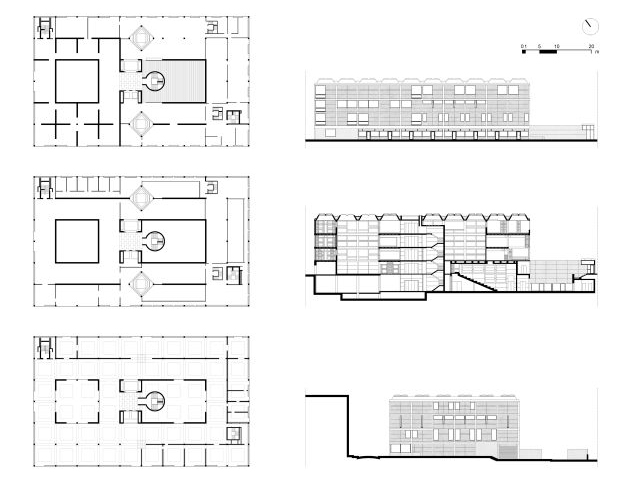

Fig.

3 - Louis I. Kahn. Yale University Art Gallery. Piante, prospetti su

York street e Chapel street, sezione. Disegno di Roberta Esposito.

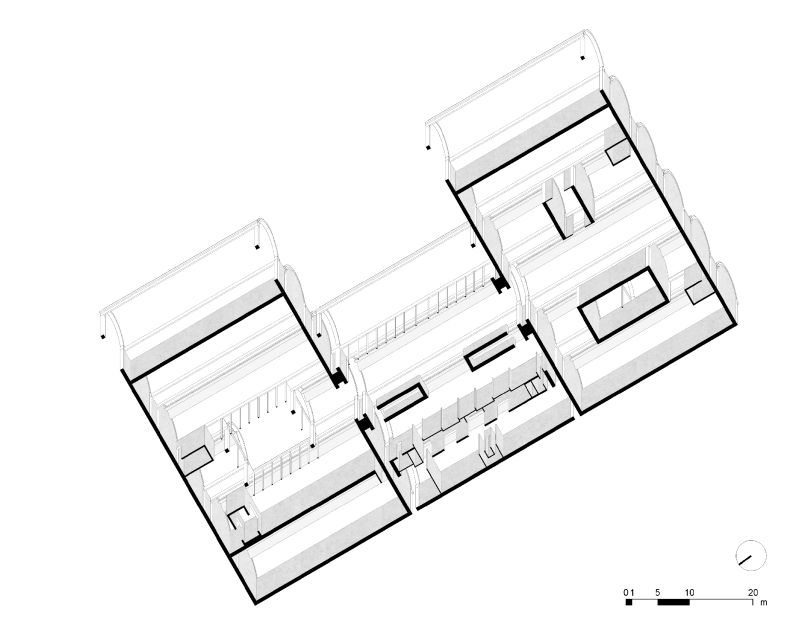

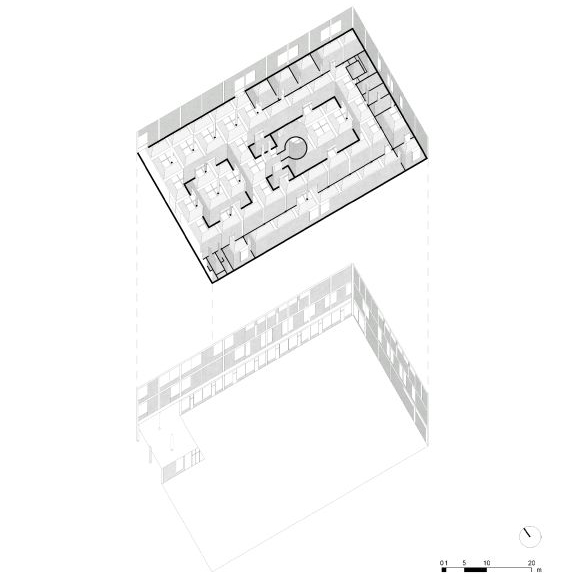

Fig.

4 - Louis I. Kahn. Kimbell Art Museum. Assonometria. Disegno di Roberta Esposito.

Fig.

5 - Louis I. Kahn. Kimbell Art Museum. Piante, sezione e prospetto. Disegno di Roberta Esposito.

Fig.

6 - Louis I. Kahn. Yale Center for British Art. Piante, prospetto su

Chapel street, sezione, prospetto su High street. Disegno di Roberta

Esposito.

Fig.

7 - Louis I. Kahn. Yale Center for British Art. Assonometria. Disegno di Roberta Esposito.

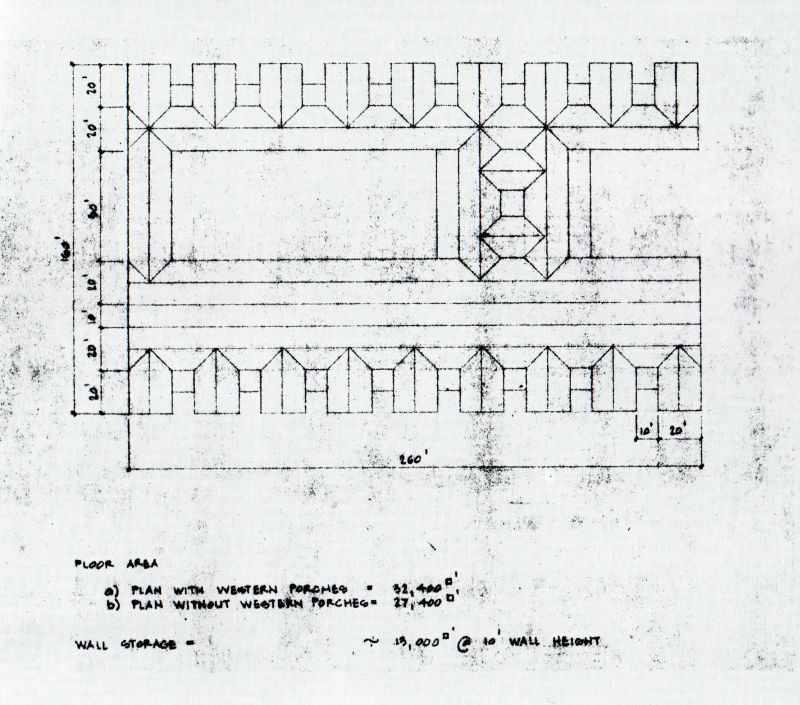

Fig.

8 - Louis I. Kahn. De Menil Museum. Pianta delle coperture. Fonte: P.

Cummings Loud, Louis I. Kahn. I musei, Electa, Milano 1991.

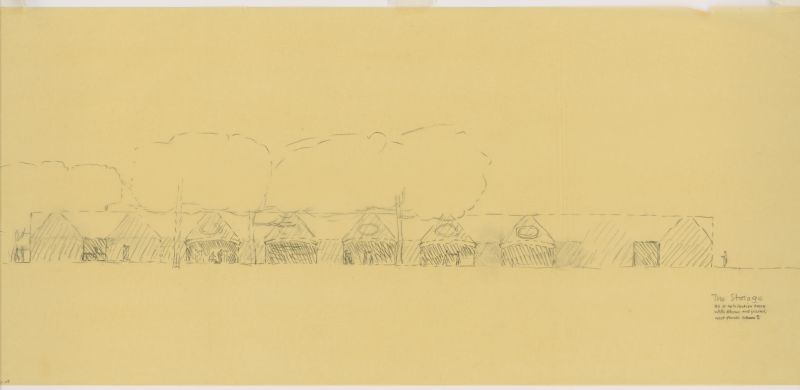

Fig.

9 - Louis I. Kahn. De Menil Museum. Prospetto. © Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Fig.

10 - Peter Greenaway. Italy of the city, Shanghai 2010.

Fig.

11 - Peter Greenaway. Italy of the city, Shanghai 2010.