Fig.

1 - Rodolfo Lanciani, «Forma Urbis Romae», table VIII. Topographic map of Rome, 1901

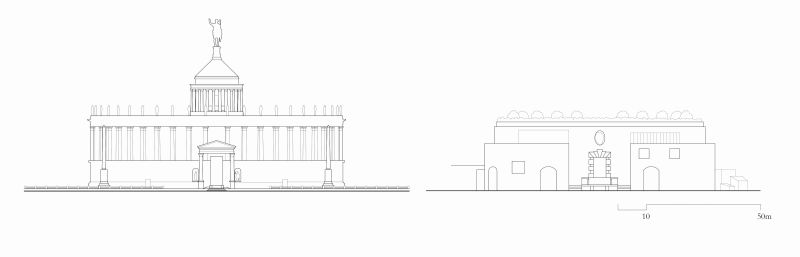

Fig.

2 - Rachele Lomurno, Mausoleum of Augustus’

reconstruction (left) Soderini garden’s reconstruction

(right). Based on Sistema Informativo Archeologico, Sapienza

Università di Roma, courtesy of Prof. Paolo Carafa

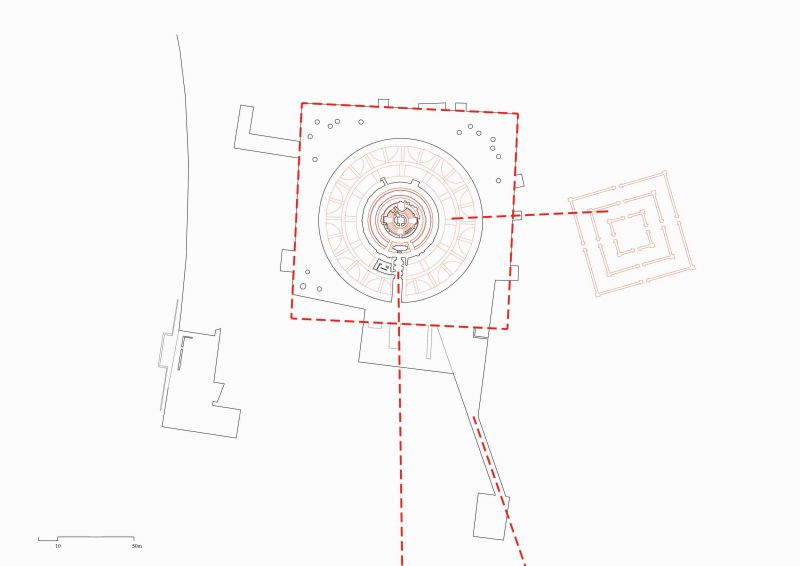

Fig.

3 - Rachele Lomurno, Planimetry of the project by ABDR. Critical

redrawing by the author based on the competition drawings.

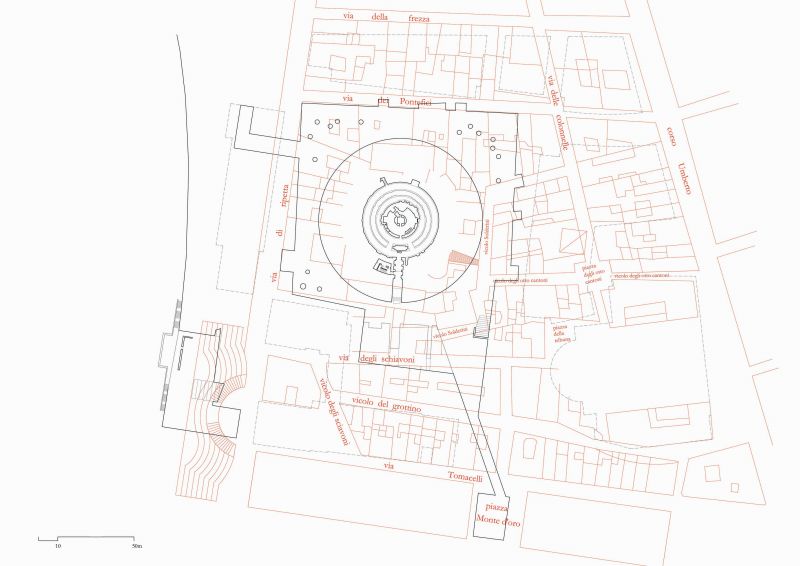

Fig.

4 - Rachele Lomurno, archaeological level plan of the ABDR

project with reconstruction of the Mausoleum of Augustus. Critical

redrawing by the author based on the competition drawings.

Fig.

5 - Rachele Lomurno, archaeological level plan of the ABDR

project with reconstruction of urban fabric in the Reinassance era.

Critical redrawing by the author based on the competition drawings and

on the “Nuova pianta di Roma” di Giambattista Nolli

(1748).

Fig.

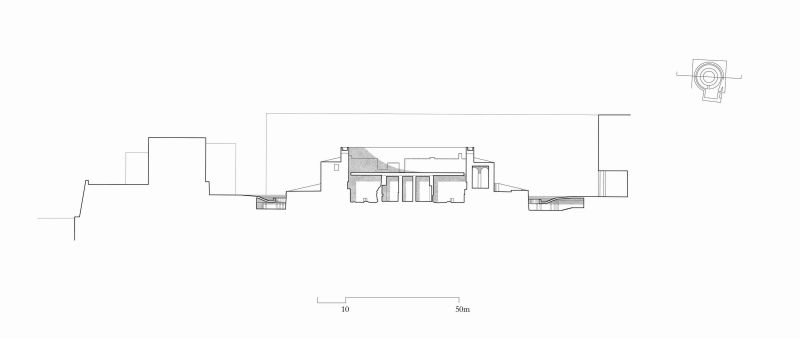

6 - Rachele Lomurno, Cross section of ABDR project. Critical redrawing

by the author based on the competition drawings. In evidence the two

important quotes of the project: the first of the “museum of

Augustus sepulcher” and the second of the “new Soderini

garden”.