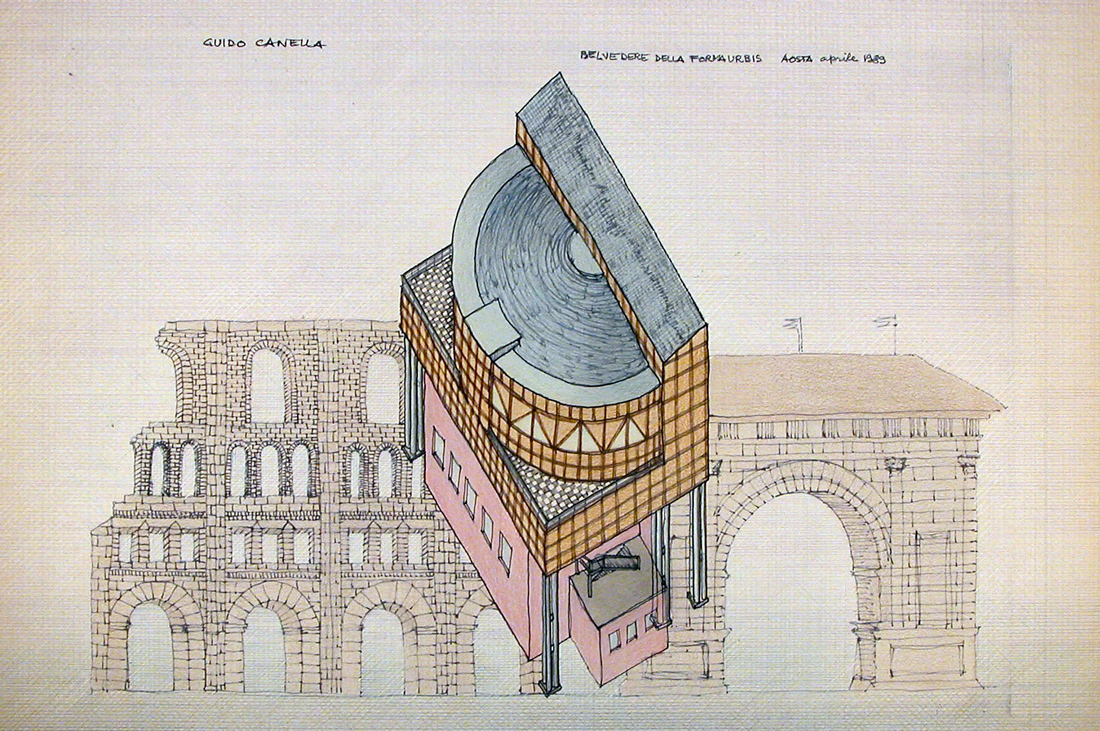

Fig.

1 - Guido Canella, Teatro-museo della forma urbis, Aosta,

1988. Archivio Eredi Canella.

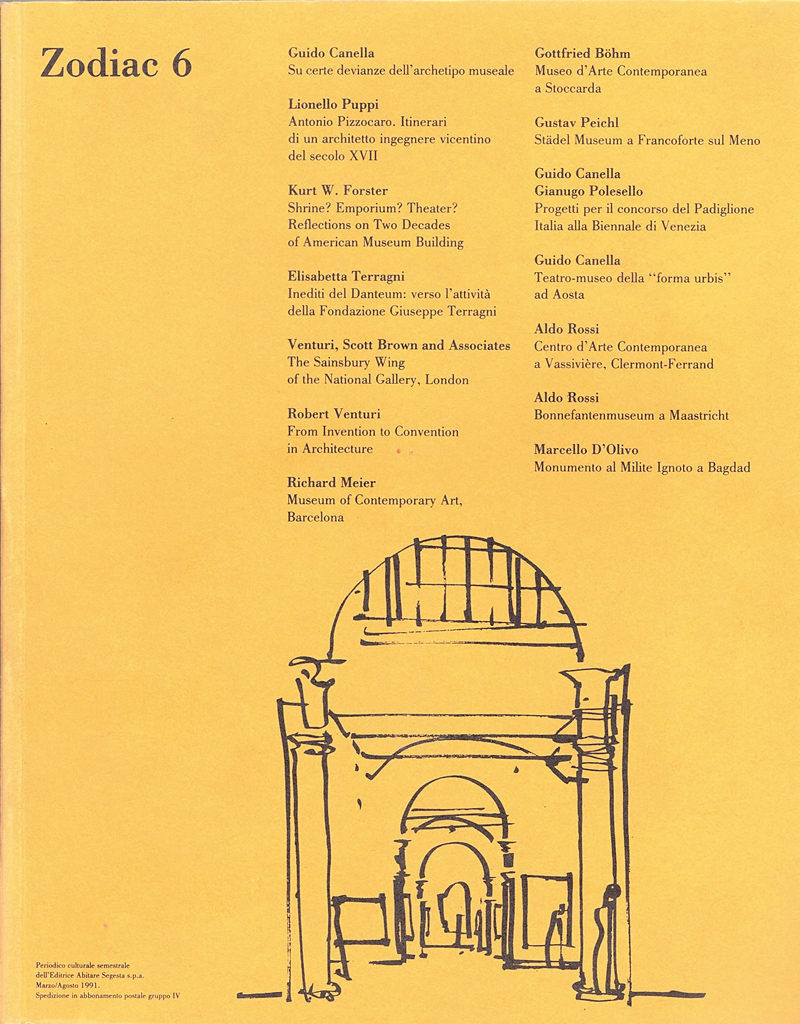

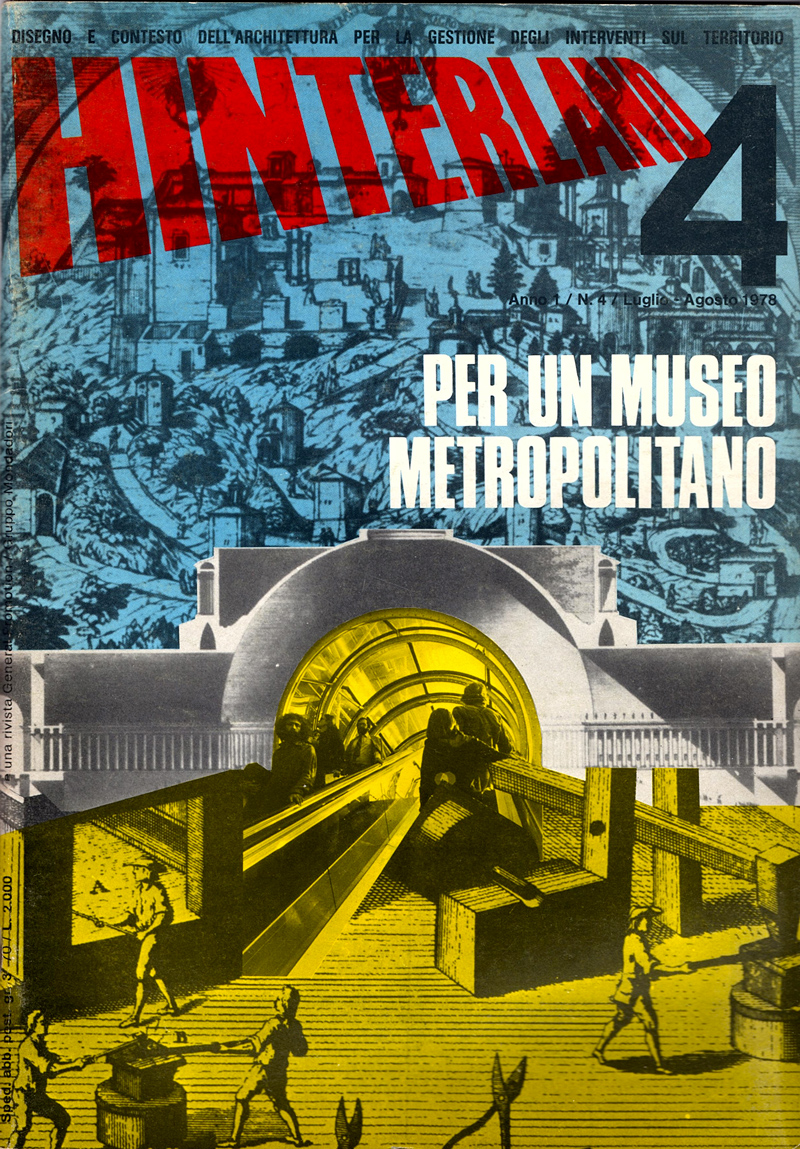

Fig.

2-3 - The covers of “Hinterland” nos. 4/1978 and 21-22/1982, dedicated to museums.

Fig.

4 - The cover of “Zodiac” no. 6/1988 dedicated to museums.