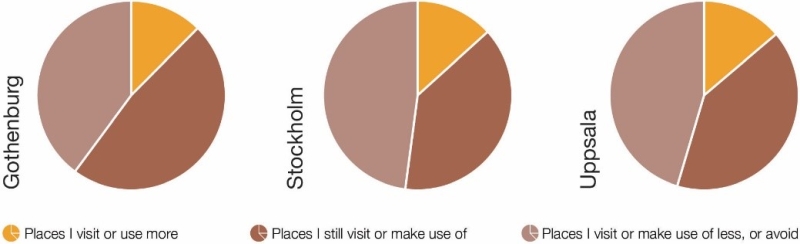

Fig.

1 - The distribution between places, all three cities.

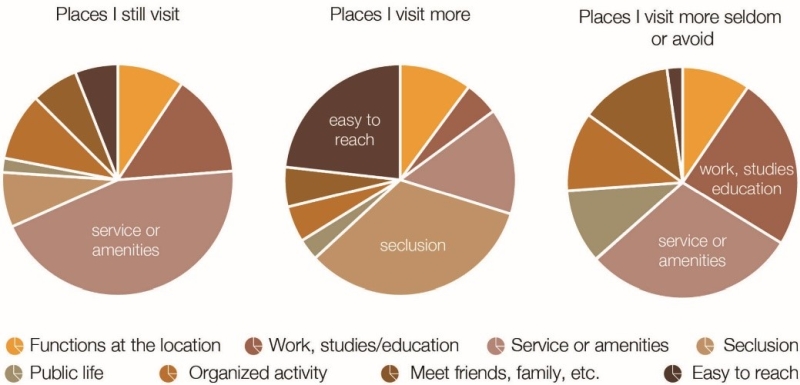

Fig.

2 - The distribution of uses.

Fig.

3 - The distribution of uses.

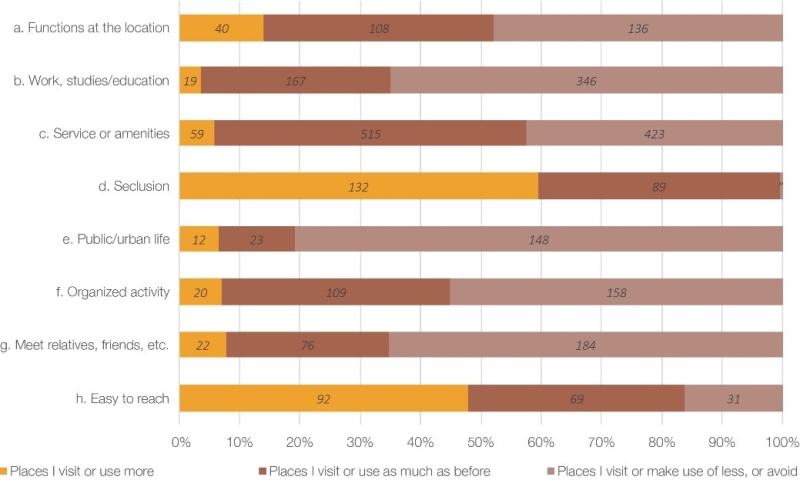

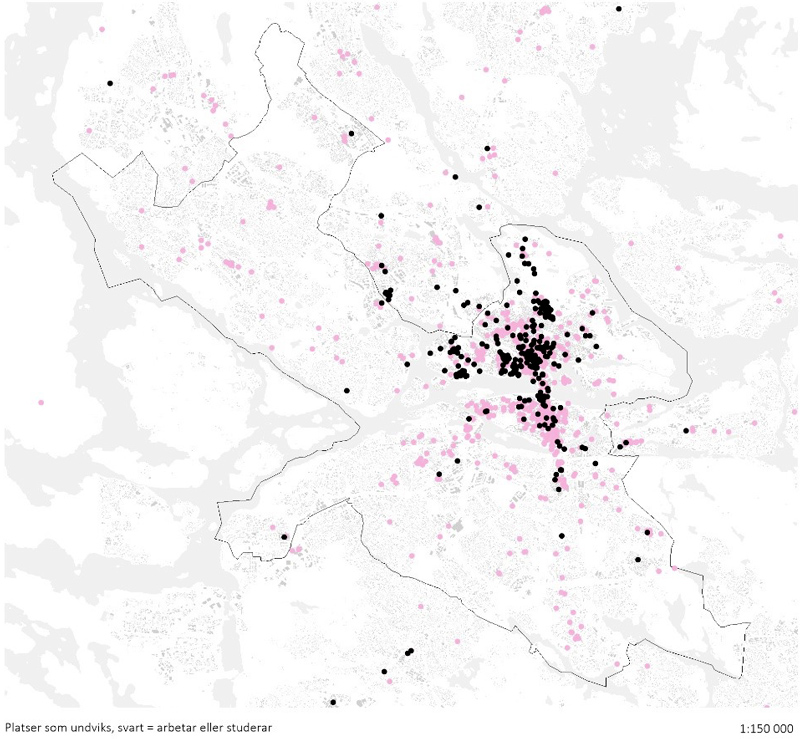

Fig.

4 - Places avoided, where those related to work/study, are marked in black.

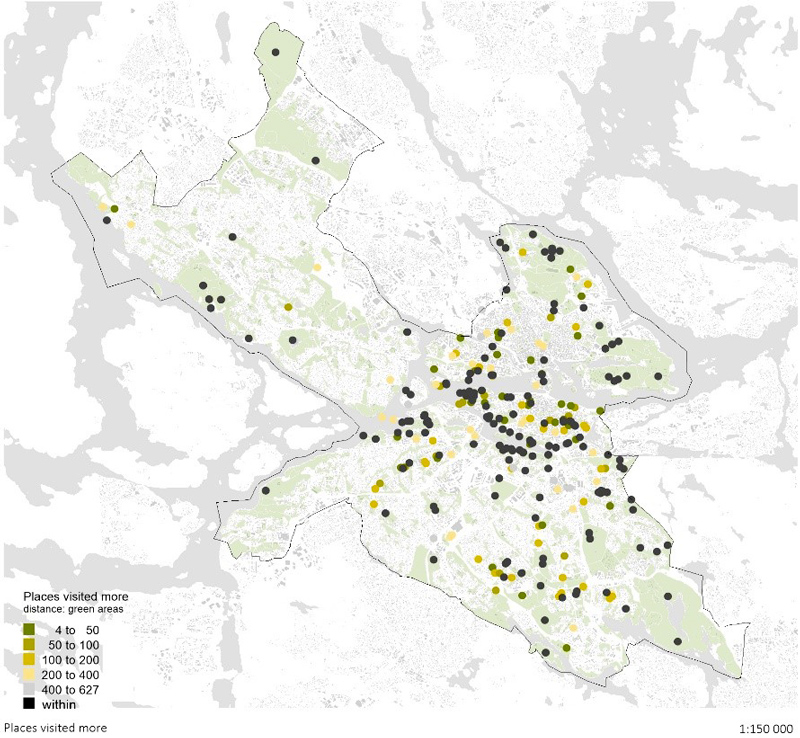

Fig.

5 - Places visited more and their relation to parks and nature