Fig.

1 - Selection of the bibliographic sources reviewed. The magazines belong to the Passarelli Fund.

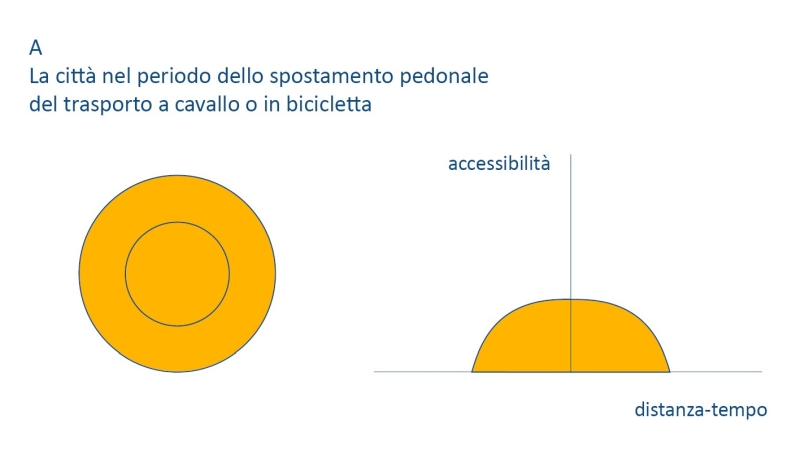

Fig.

2 - Schematization of the city’s structure and its

accessibility features. The drawings illustrate three primary phases of

urban development in relation to evolution in technology and

communications (reproduced from Allpass et alii 1968).

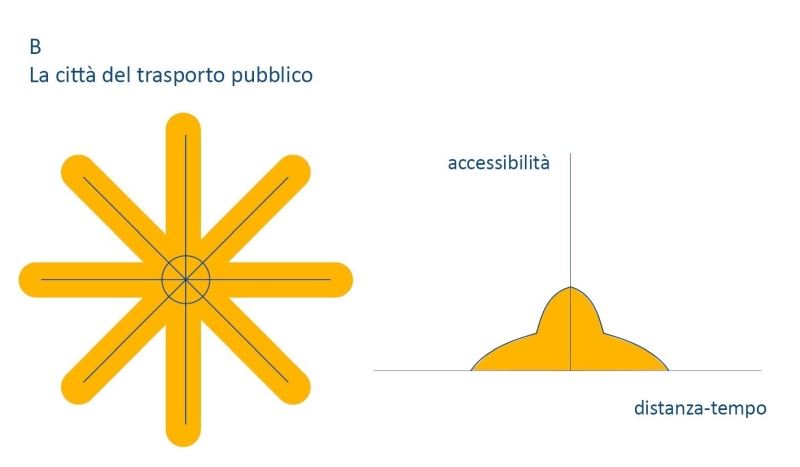

Fig.

3 - Schematization of the city’s structure and its

accessibility features. The drawings illustrate three primary phases of

urban development in relation to evolution in technology and

communications (reproduced from Allpass et alii 1968).

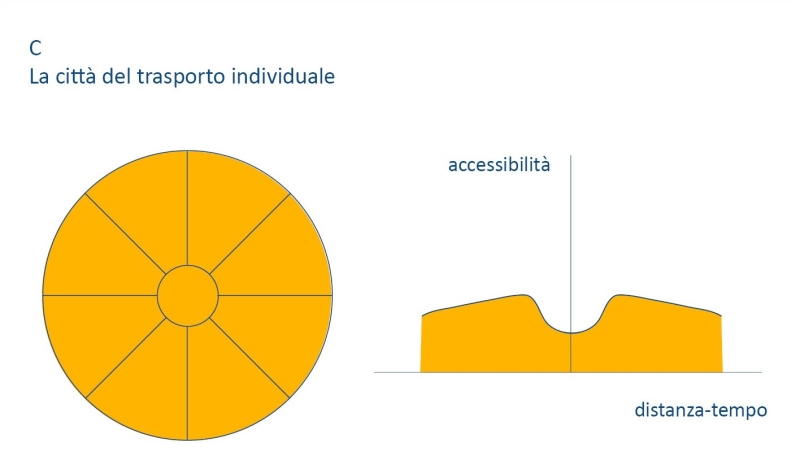

Fig.

4 - Schematization of the city’s structure and its

accessibility features. The drawings illustrate three primary phases of

urban development in relation to evolution in technology and

communications (reproduced from Allpass et alii 1968).