Fig.

1 - Poster of the Workshop Presenze scultoree nel chiostro, nel

recinto, nel parco [Sculptural Presences in the cloister, in the

enclosure, in the park], CSAC, Parma 2016.

Fig.

2 - Pictures from the Workshop lessons. Photos by Paolo Barbaro.

Fig.

3 - Pictures from the Workshop lessons. Photos by Paolo Barbaro.

Fig.

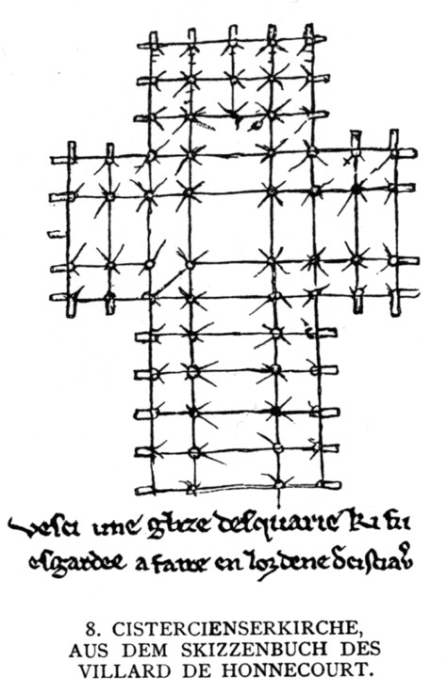

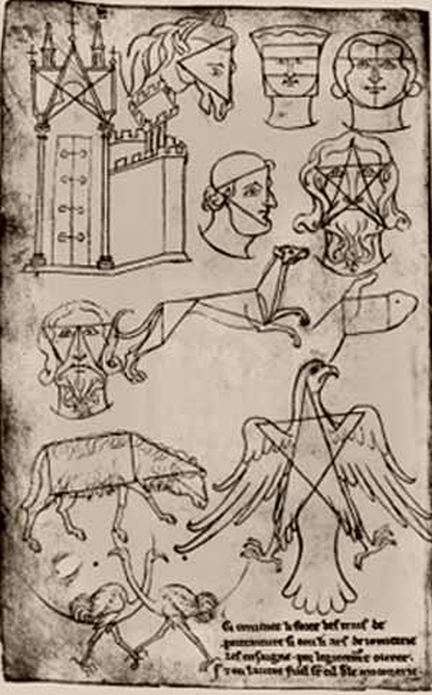

4-5 - Villard de Honnecourt, Drawings from the Notebook, 13th century.

Fig.

6 - Baptistery of Parma

Fig.

7-8 - Abbey of Valserena and centuriation of the Parma area.

Fig.

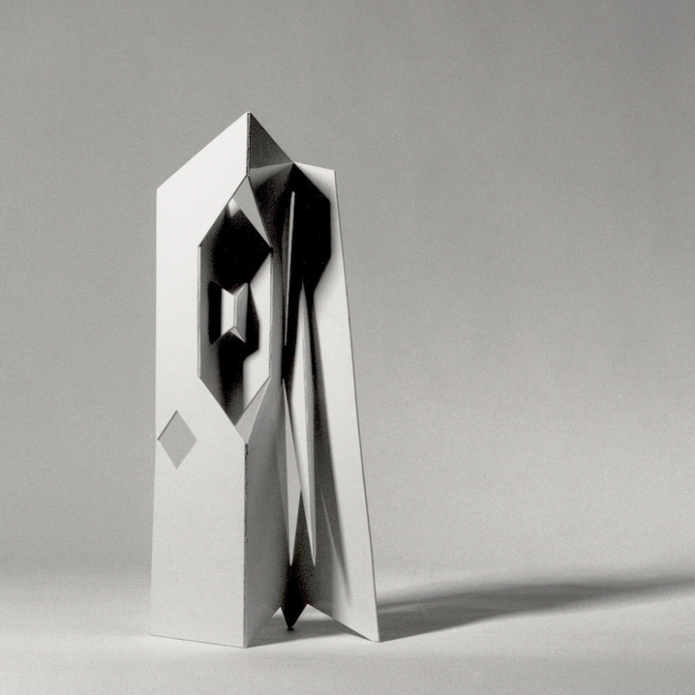

9 - Bruno Munari, Scultura da viaggio, 1959.

Fig.

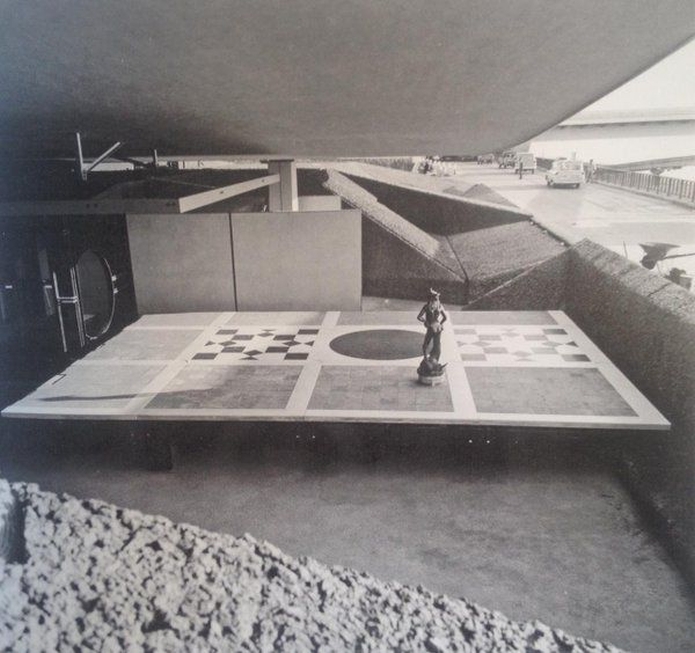

10 - Carlo Scarpa, Poetry Section, Italian Pavilion at Expo 67

Montréal.

Fig.

11 - Agnes Denes, Wheatfiel, 1982.

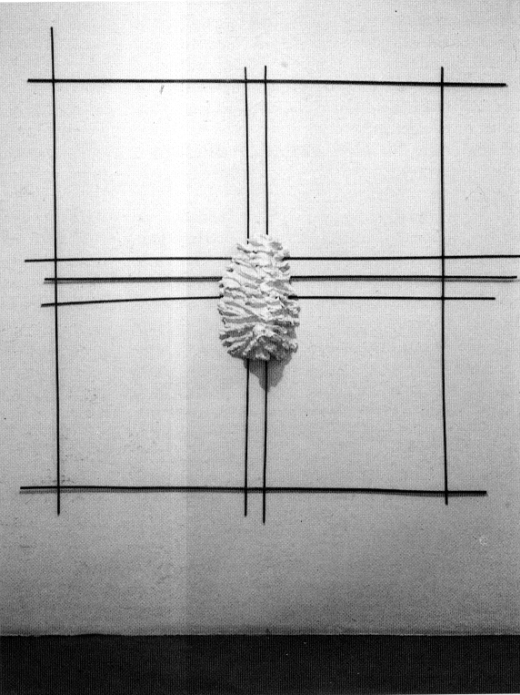

Fig.

12 - Paolo Icaro, 1991.

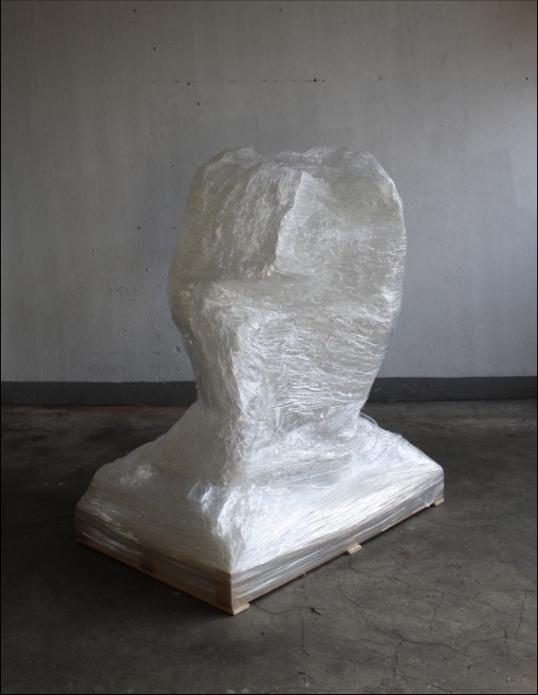

Fig.

13 - Alice Cattaneo, Untitled, 2016.

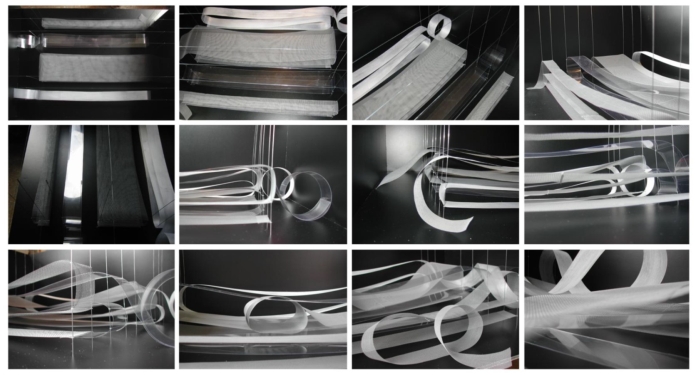

Fig.

14 - Alis Filliol, Ultraterra, 2016.

Fig.

15 - Luciano Fabro, Lo spirato, 1973. Photo by G.Ricci.

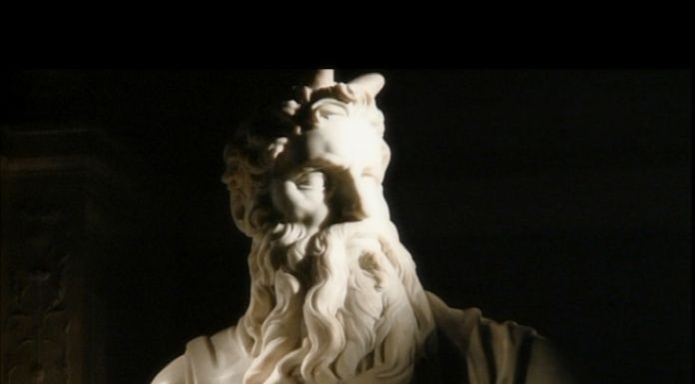

Fig.

16 - Still from Michelangelo Antonioni's film, Lo sguardo di Michelangelo, 2004..

Fig.

17 - Orazio Carpenzano, Project for Sylvatica, 2005

Fig.

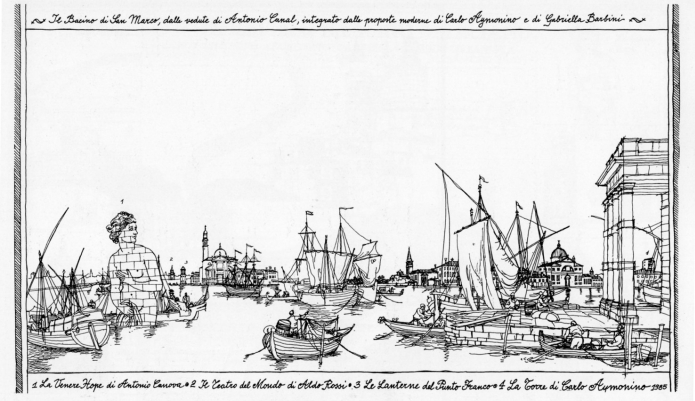

18 - Carlo Aymonino, Gabriella Barbini, Project for the completion of

St. Mark's basin, Third International Architecture Exhibition, Biennale

di Venezia, 1985.

Fig.

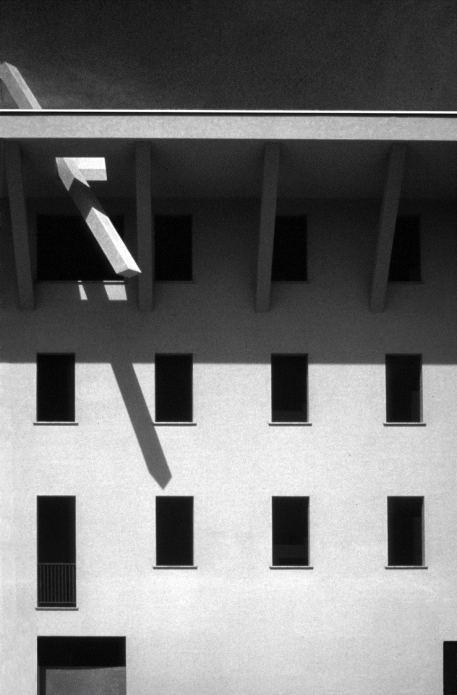

19 - Franco Purini, Pirrello House, Gibellina, 1990.

Fig.

20 - Franco Purini at the Workshop, Abbazia di Valserena, Parma 27 july 2016. Photo by Paolo Barbaro.

Fig.

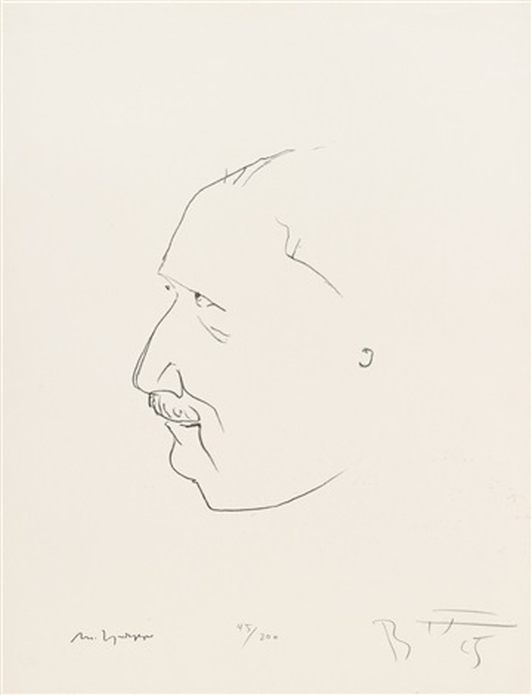

21 - Portrait of Martin Heidegger by Bernhard Heiliger, 1965.

Fig.

22 - Round table Starting from Body and space by Martin Heidegger,

Cloister of the Abbey of Valserena, Parma, July 22, 2016. Photo by

Paolo Barbaro.