Fig.

1 - Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos.

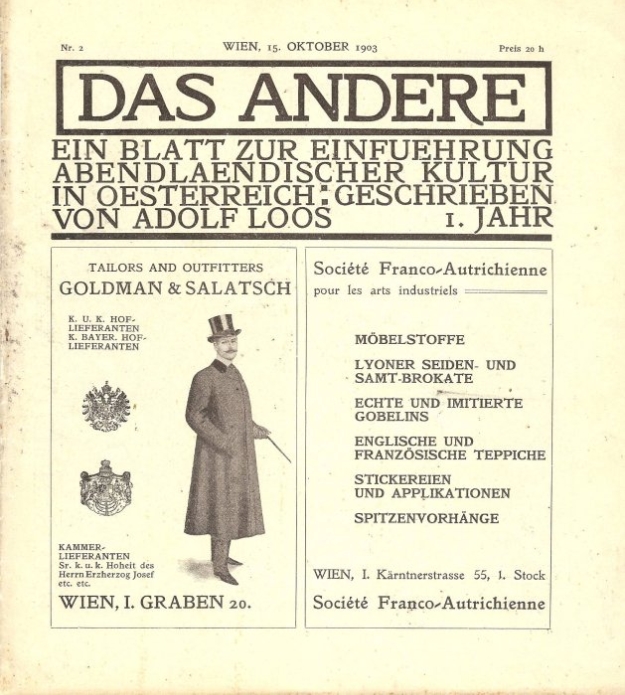

Fig.

2 - Frontispiece of the magazine edited by Adolf Loos DAS ANDERE, II,

1903.

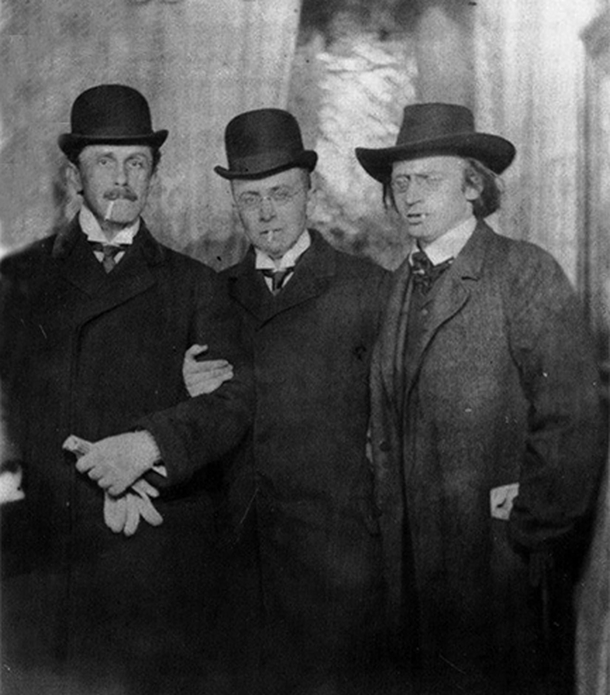

Fig.

3 - Adolf Loos with Karl Kraus and Herwarth Waldenl, 1909.

Fig.

4 - Adolf Loos tend the ear, Dessau, 1931.

Fig.

5 - Adolf Loos with his second wife, the actress Elsie Altmann, 1921

Fig.

6 - Adolf Loos in America, 1895.

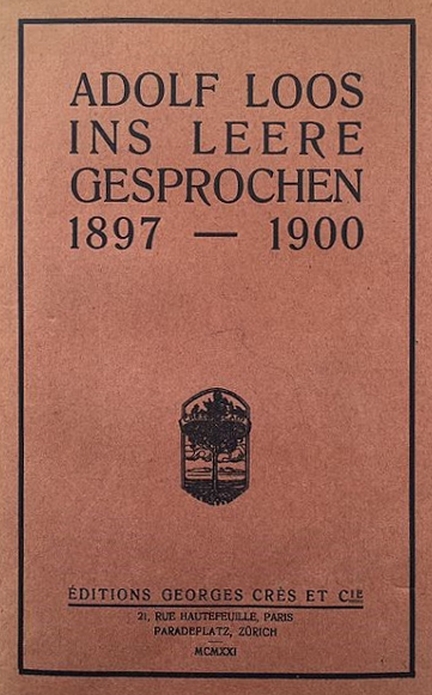

Fig.

7 - First edition of Words in the void, published in Paris and Zurich in 1921.

Fig.

8 - Inauguration of the Café Museum. Adolf Loos standing to the right, April 19, 1899.

Fig.

9 - Living room at the Müller house

Fig.

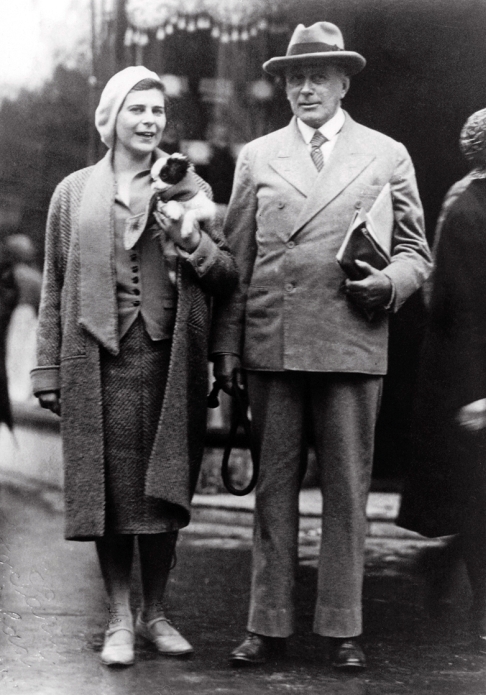

10 - Adolf Loos with Claire Back, on their wedding day, July 1929.

Fig.

11 - Adolf Loos with Claire Back and Kiki, their Japanese dog,

1930.

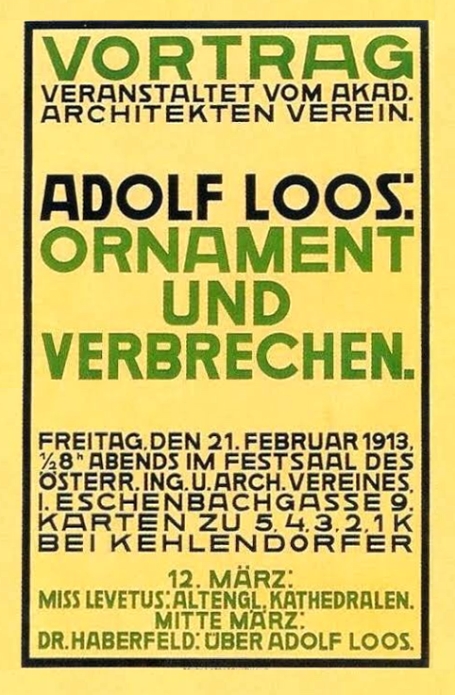

Fig.

12 - Ornament und Verbrechn, poster of the public conference of March 12, 1909.

Fig.

13 - Adolf Loos with Lina Loos Obertimpfler, Peter Altemberg and Heinz

Lang, 1904.