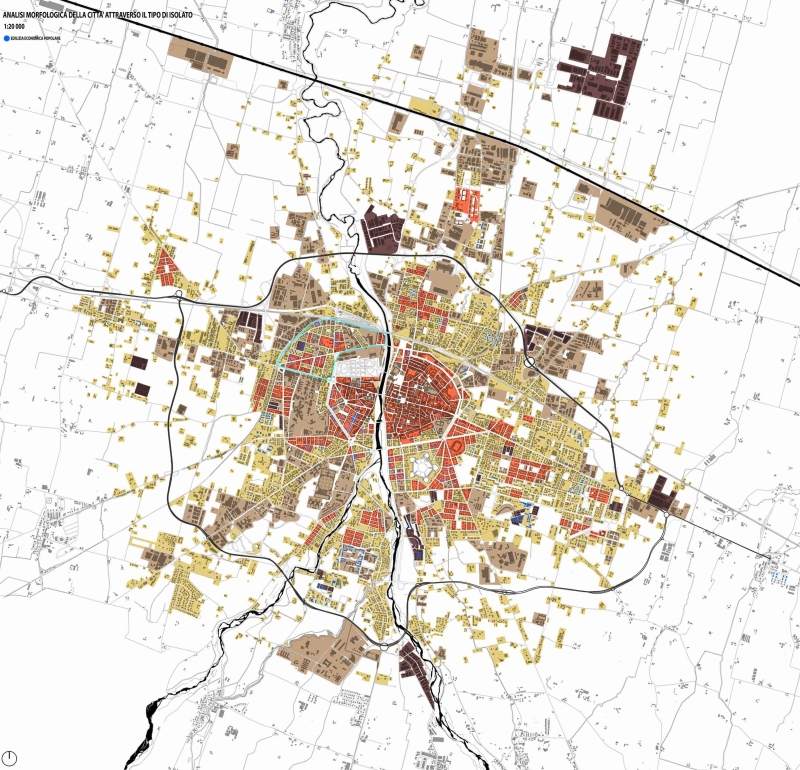

Fig.

1 - Analysis of the city of Parma through the typologies of the block.

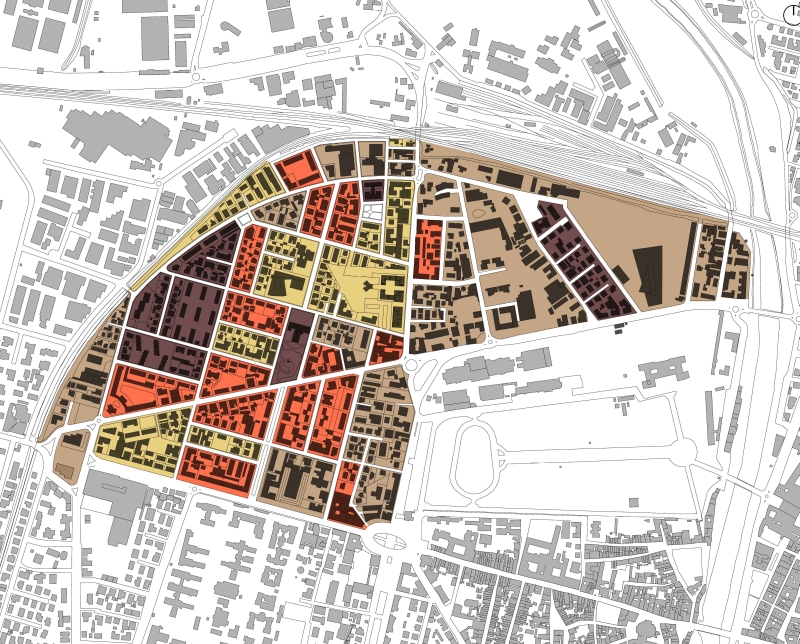

Fig.

2 - Analysis of the Pablo district of Parma through the typologies of the block.

Fig.

3 - Reconfiguration of the fabric of the Pablo district through the

experimental model of the macroblock. Design experimentation on a

fabric sample (macroblock 2).

Fig.

4 - Components of urban regeneration of macroblock 2.