Typological research for post-war school buildings in Milan.

Arrigo Arrighetti pioneer of modernity

Annalucia

D’Erchia

Fig.

1 - Mostra dell’Edilizia Scolastica; Rome, 1956. ASC Fondo Arrigo Arrighetti, Scatola C, busta 35.

Fig.

2 - Exhibition in the contest of Convegno sull’edilizia

scolastica dei grandi centri urbani; Milan, ASC Fondo Arrigo

Arrighetti, Scatola C, busta 85.

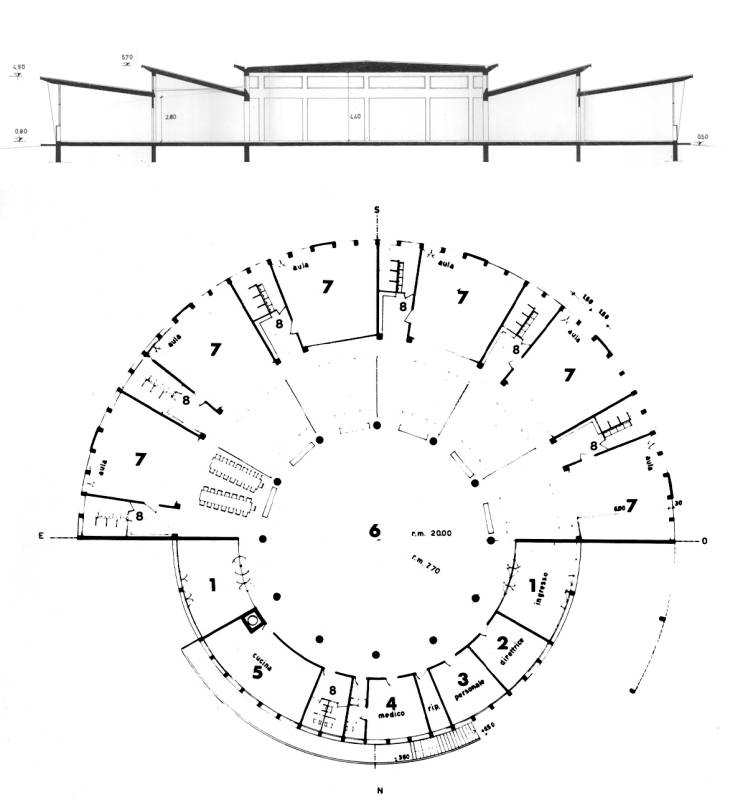

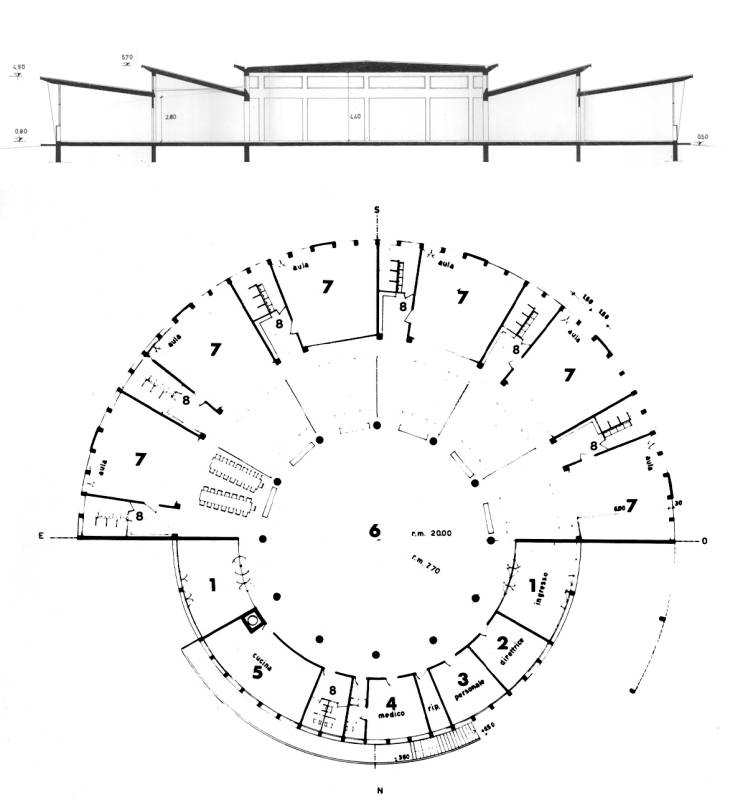

Fig.

3 - A. Arrighetti, Nursery school at Villapizzone (1959). Section and plan.

Archivio del Comune di Milano, Cittadella degli Archivi

1. entrance; 2. headmistress, 3. staff, 4. doctor, 5. kitchens, 6. activity room, 7. classrooms, 8. toilets.

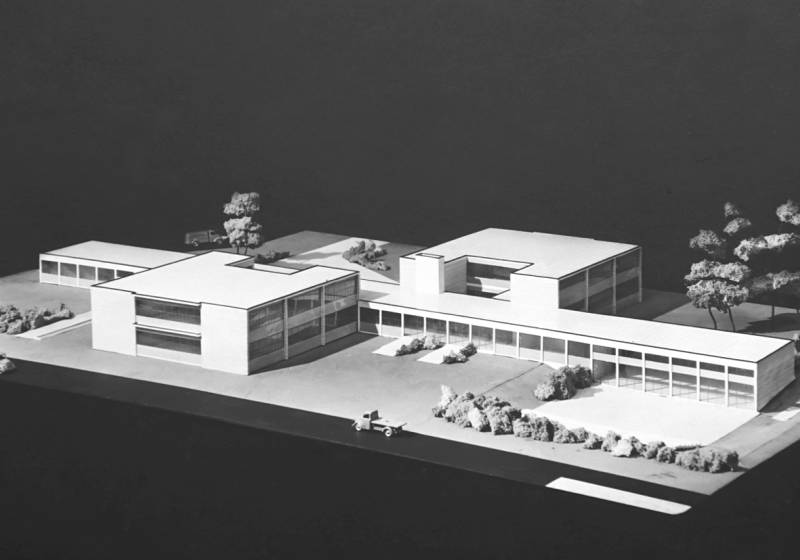

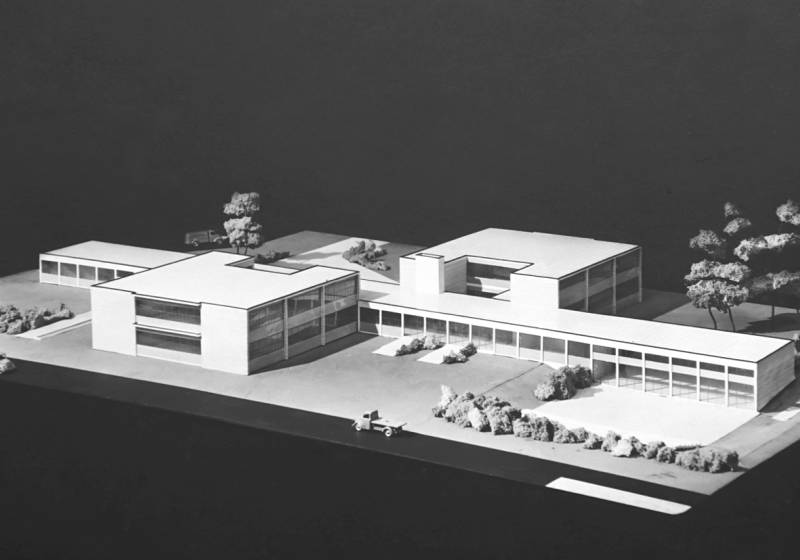

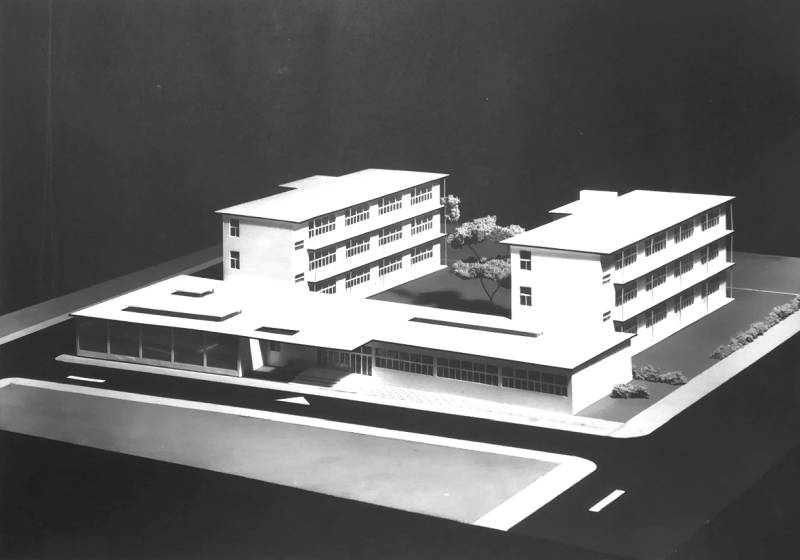

Fig.

4a - A. Arrighetti, Primary school at Comasina district (1956) Study model. ASC Fondo Arrigo Arrighetti, Scatola C, busta 25

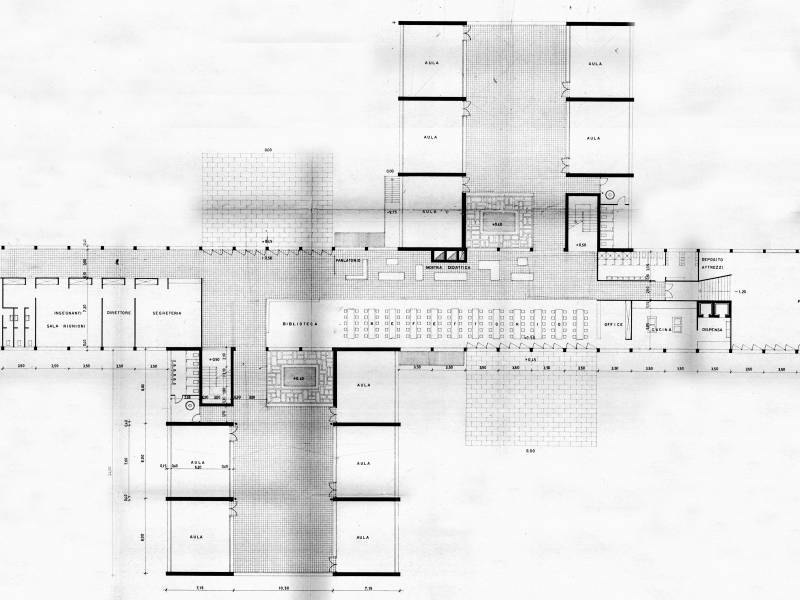

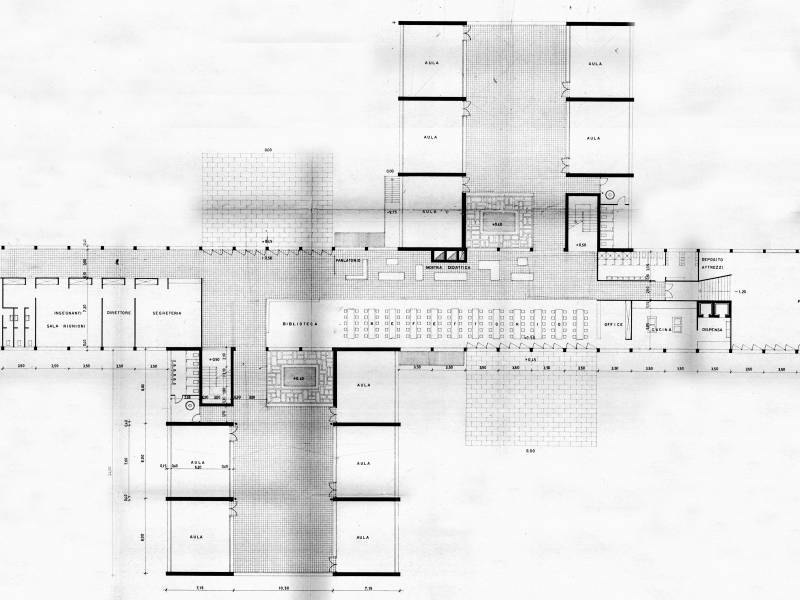

Fig.

4b - A. Arrighetti, Primary school at Comasina district (1956) Ground Floor. ASC Fondo Arrigo Arrighetti, Scatola C, busta 25

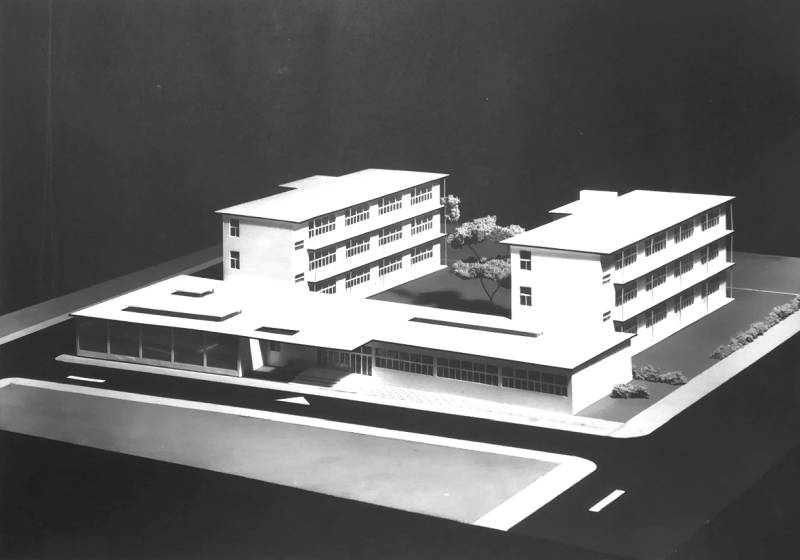

Fig.

5 - A Arrighetti, Middle school Carlo Porta, via Moisè Loira. First projet study model.

ASC Fondo Arrigo Arrighetti, Scatola C, busta 28.

.

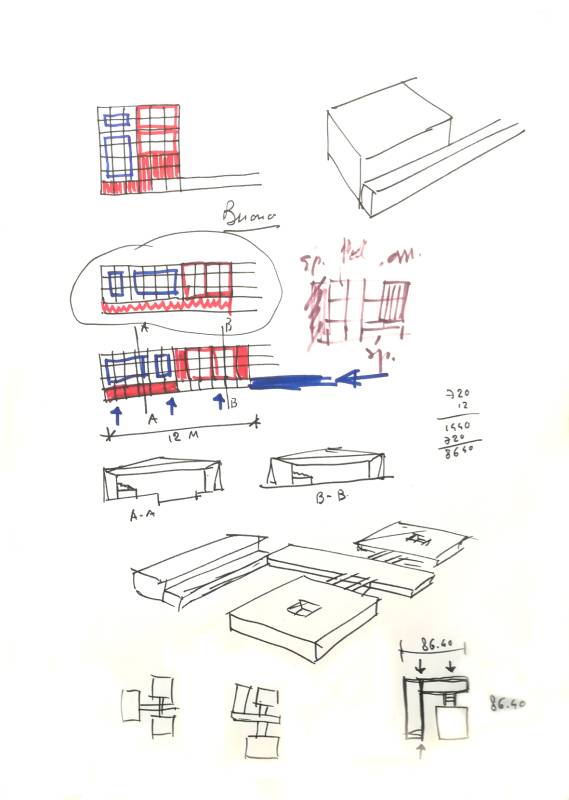

Fig.

6 - A. Arrighetti, Civica Scuola Alessandro Manzoni, 1958. Ground floor plan.

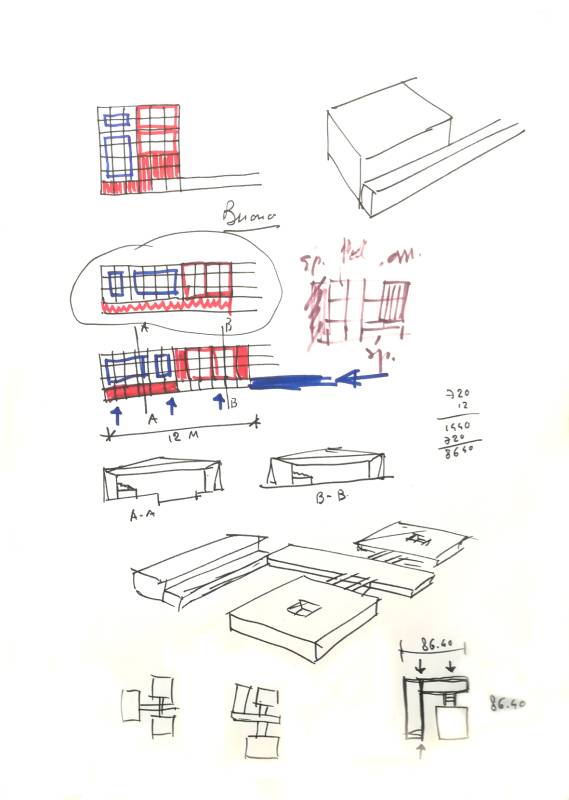

Fig.

7 - A. Arrighetti, Study sketches for new types of school buildings. ASC Fondo Arrigo Arrighetti, Scatola B, busta 47.

«I spent days breaking down and reassembling [...],

I devised new rules of the game, I drew hundreds of schemes [...] I

felt that the game made sense only if it was set up according to

certain strict rules [...] suddenly, the idea flashed through my mind

that I could try again in another way, simpler, quicker, more

successful. I began again to compose schemes, to correct them, to

complicate them: I got entangled again in this quicksand, I closed

myself in a maniacal obsession». (Calvino 1973)

The sharing of narrative composition processes to which

literature has sometimes accustomed its readers almost seems to be the

underlying narrative in describing the collection of work notes

ordered, with precision and care, in the envelopes of the Arrigo

Arrighetti fund kept today in the Archivio Storico Civico del Castello

Sforzesco in Milan; a series of reasonings in the form of words and

diagrams traced on loose pages and catalogued by the architect himself

as new types of school buildings.

A maniacal obsession with doing and

redoing moves Arrighetti in the tension of an ever more precise

agreement between the meaning of the theme of the school, which changes

by its very nature, and the clarity of the signifier through which this

theme is declined each time; a language, this system of meanings and

signifiers, which interprets and narrates the structure of the facts.

Calculations and annotations, signs and numbers, matrices and

grids regulate the arrangement of teaching groups defined by pedagogical

units and services that are

distinguished for the first time with this clarity into school services

and city services. Recurring elements that sometimes intersect and

contaminate, often connect, always recognize each other and that, just

like notes, illustrate the statement of the Final Report of

the commission for the study of the typology of

school buildings[1]

of which Arrighetti was a member[2].

These reflections had to be placed in a developmental

perspective; «foreseeing not only the future outlets of

trends already in progress, but also to a certain extent promoting them

through experimentation». Principles of a general nature that

are capable of declining themes dear to the post-war debate and central

to Arrighetti’s own research.

A research, but above all an attitude towards research that

recognizes, in the experiences that have preceded us, modernity in the

interpretations and actuality in the way of verifying them yesterday as

today through the different scales of the project.

At the date of these reasonings made of signs, Arrighetti had

already completed his work at the Ufficio Tecnico del Comune di Milano,

where, as architetto condotto, he had designed

and built over fifteen new schools in just six years, between 1955 and

1961, some of which, studied and designed as prototypes, had been built

in several examples.

Schools of every order and degree were distributed throughout

the fabric of Milan, according to the strict rules

of the urban planning of the new regulatory plans, in the best

location, identified by interweaving demographic forecasts and density

indices.

The Ufficio Tecnico, under the direction of Arrighetti, played

a central role in the school issue, sharing its work during study days[3] dedicated

to the subject and taking part in exhibitions[4], occasions for comparison

during which the state of the art of school building in Italy was

illustrated through panels and scale models.

Arrighetti understood that the strength of a conscious and

reliable study was the ability to «accumulate design

experience and apply it into the projects to be drawn up»

(Arrighetti 1961). For this reason, within the Ufficio Tecnico, he set

up a Ufficio Studi e Progetti Edilizi in which

the design was supported by a series of in-depth studies on the

subject, and therefore «set up in such a way that the

information and study part acquired a prominent value in the work. In

other words, the material drafting of the drawings became the final act

of a complete examination of all the data on the problem»

(Arrighetti 1961).

This focus on in-depth knowledge of the subject was a specific

feature that had given the Ufficio’s work wide acclaim in the

scientific community and was also followed with interest by the

Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione which published some of the new

projects as exercises in its Quaderni[5] edited by

the Centro Studi per l’edilizia e

l’arredamento della scuola directed by Ciro

Cicconcelli[6].

Arrigo Arrighetti was one of the first interpreters of this

open dialogue between different disciplines, attempting to translate

both the renewed pedagogical idea and the experiences of specialists in

different fields into the most appropriate architecture, regretfully

recognizing the missed opportunity to design new buildings for

education even within the historical fabric of Milan, where schools

«are buildings adapted for schools and the buildings built to

serve as schools are now old, dilapidated and outdated».

The concept of school, as taught by

modern pedagogy, had completely changed. Knowledge and the acquisition

of disciplinary norms were no longer imposed but conquered by children

and young people, and the school environment played a primary role in

this conquest.

«The architectural space of the school cannot be the

same at all ages and in all places. [...] So the traditional school is

gradually being replaced by a school which, instead of being made up of

a series of classrooms and disengaged by corridors or porticoes, is

organized in functional units, each of which is

almost self-sufficient, but united to the center of common life, to

those environments, such as the auditorium, the library or the small

theatre, which also serve the community. Just as a city is organized

into families, neighborhoods, districts, so a school is organized into

groups of pupils, classrooms comprising the various groups, functional

units or districts, a set of functional units». (Cicconcelli

1958)

Thus, Arrighetti’s investigation also starts from

the idea of the school as a small community and becomes a community

center «as a building that houses a basic institute of

collective living» (Arrighetti 1957) and, from degree to

degree, tackles the subject and interprets it, adding complexity.

This tension towards the most fitting architectural

translation already concerns the first degrees of education, the

nursery school, which is «a small new world to discover.

[...] a world made of light and color, of stones and blades of grass.

Of elementary forms [...] as simple as the soul of a child»

(Arrighetti 1956).

The first experience of collective living is variously

interpreted by Arrighetti, but perhaps the principle that best

corresponds to this idea of a small community is the one that can be

recognized in the nursery schools imagined between 1957 and 1959[7], which

reflected on the theme of the central square around which the

classrooms were arranged, small autonomous units.

In Villapizzone (1959) the central, circular square, covered

by a single roof supported by columns, is the place where the

children’s community used to gather and meet for collective

activities. Six autonomous nuclei, each with its own cloakroom, which

becomes an entrance and vestibule to the toilets, and a refectory

space, which stands between the classroom unit and the central square,

are arranged in a fan-shape and each opens out towards a portion of the

garden, an open-air extension of the classroom space.

The gap between the space of the classrooms and that of the

school services, where the more public part of the management and staff

still coexists undivided with the more school-related part of the

children’s school, with the doctor’s surgery and

kitchens, is identified by the retreat of the covered but cold

entrances which, by generating deep shadows, make them even more

recognizable. They lead directly to the collective space from which the

children, crossing the small tables in the lunchroom, enter their

actual classroom.

The discontinuity of use is also identified and recognized by

the size of the construction radius of the second semicircle, which can

be read as a subtraction from the complete footprint on the ground of

the circular sector whose size coincides with the size of the classroom

– toilet block.

This geometric clarity is confirmed in the elevation, which

identifies, through the different heights of the roofs, the higher

square, the circular sector of the services and the south-facing sector

of the classrooms, whose screening is entrusted to the succession of

pillars, tapering downwards, which construct the façades,

and to the generous overhang of the roof, which protects the

full-height windows from direct light.

But Arrighetti already had occasion to reflect on this idea of

a school-community a few years earlier. In 1956,

in fact, he had been called upon to oversee the design and construction

of the nursery and primary school in the new self-sufficient Comasina

neighborhood in the north of Milan.

The primary school imagined for the children of the district

becomes itself a composition of neighborhood units.

It is generated from the nucleus of the school section

of five classrooms. Together with the toilet block, these classrooms

define the size of the long side of the collective activity space where

the children grow up together and share experiences, and which they all

face, leaving the short sides free to let in light. The need to build

four sections led to the idea of a two floors system which, mirrored

and shifted by a span, clings together with its twin to a central

spine, a street which not only distributes but contains the

school’s services in its linear body. Near the entrance we

can recognize the administrative services, the medical clinic, an

exhibition space and a small library used by the children. At the top,

to the west, is the caretaker’s accommodation, with its own

dedicated entrance, located in the portion closest to the residential

part of the neighborhood, while on the opposite side, towards the

garden, is the gymnasium, adjacent to the cafeteria, which, following

the slope of the land, descends to allow greater internal height and

the roof to rest continuously. A pedestrian street separates the

primary school from the nursery school, a small school district within

the neighborhood.

The same pedagogical idea is made more articulate by the

increasing complexity of the higher level. The Carlo Porta middle

school (1958) in Via Moisè Loira is an expression of similar

reasoning and solutions, with particular attention paid to the spaces

for study and collective work between pupils and teachers and the

services, still linked to the exclusive use of the school, but which

seek in their disposition a relationship with the city. In fact, even

more strongly than in the initial project, the gymnasium, reaching out

to the edge of the block, seems almost to elect itself as a place for

the public, unlike the other parts which, set back, declare themselves

related to the school.

The idea of neighborhood unity remains

in both projects, consisting of three classrooms in sequence,

distributed by a single path culminating in the collective classroom

facing the garden, and arranged in two blocks of three floors each.

The north-facing loggias of the first project are replaced by

a system of projecting brise soleil placed one third of the way up the

window openings, to the south, allowing two different types of light to

enter. Attention to the theme of natural light inside the school

building and the use of architectural expedients to regulate it had

been explored in those years during the design of the primary school

for children suffering from amblyopia (1955), which had led Arrighetti

to investigate this theme with specialists and to build not only

specific furnishings but also 1:1 scale models of the classroom space,

verifying and evaluating the most suitable solutions together with the

doctors. These dialogues had evidently become the basis for many

subsequent experiences.

In the case of the Special School, it

was not the idea of community that drove the typological research and

the choices of the project but the strong need to guarantee the

right to education for all and, using medical knowledge and

the tools of architecture, to build the best possible space for

learning.

And this same idea of education for all

is also the basis of the project that is perhaps more complex and

certainly closer to contemporary thinking on the idea of the role of

the school in the city as an active body, one of the premises set out

in points in the commission’s report.

Secondary education for girls, conceived in a modern spirit as

early as 1861, had led to the establishment of the ‘Alessandro

Manzoni’ Civic School, which had never had its own

site. Having identified a site near Parco Ravizza, south of Milan, the

school, planned in all its parts, was soon to be started

but never built due to the change of use of the chosen land.

The longitudinal block of classrooms, which would have

occupied three of the four floors of the project, would have been

transversally intercepted by the axis along which the entrance, the

distribution on the upper floors and the cafeteria were arranged,

stretching out towards the park. Near the entrance we could recognize

the circular main hall, an auditorium facing the city, which was just

as modern, with dedicated entrances that would allow it to be used even

during out-of-school hours.

Looking back at these projects, it seems clear that the civic

role of the school, or of some parts of it, is the denominator that

unites the latest shared experiences that become the seed for the

thoughts collected in these notes.

If, on the one hand, Arrighetti became a model of a precise

and cultured way of working whose depth is unquestionable, on the

other, his research gave a strong direction to all subsequent research

in which it is not difficult to trace the matrix.

Interweaving the built and unbuilt projects, we can read the

continuous dialogue between meanings and signifiers pursued, between

theme and its interpretation, exchange of knowledge between disciplines

and translations into architecture. A dialectic that is encouraged by

questioning choices, by starting again, but not from the beginning, to

compose schemes, to correct them,

to complicate them, even and above all after

verifying them in construction.

Arrighetti outlines the data on the school problem

from a perspective in which our time is still immersed.

Even today, we are questioning the meaning of the classroom

– assuming its existence is still considered – and

the relationship between this elected place for learning and all those

annexed to it, as well as the place that makes them accessible. Even

the most contemporary experiences, developed through the comparison

between disciplines, first and foremost pedagogy, consider the

possibility of contaminating the parts. This latter aspect can be seen

in all the experiences that have been reinterpreted in this context and

which, at the time, were really experiments to be verified.

These are unfinished structures dominated by increasing

schemes according to models that arrange constant, recognizable,

familiar elements and alternate flexible parts with parts that are not,

parts dedicated more specifically to the education of learners and

public and collective parts for the school, some of which are also open

to the city. The school districts then become a system of places that

are recognizable by their very arrangement of the parts and by their

volume are recognized as collective places for the city.

It is in these experiences, therefore, that specificity is

developed in the relationship between the school and the city, both in

terms of the social role it plays and the urban design it defines.

This is a lesson that can be found in recent times, at least

as an open question, both in the results of the competitions promoted

by the Ministero dell’Istruzione or by individual

municipalities on this theme, and, more strongly, in the experiences of

certain realities, such as the South Tyrol one, which has turned this

theme into a laboratory for experimentation.

In this interpretation of the school as a pedagogical and

socially constructed idea Arrighetti’s work is certainly a

forerunner.

Arrighetti, passing on the baton, leaves us, like many others,

one of the most important teachings, that stoic attitude according to

which a fool is he who always starts over and refuses to continuously

unravel the thread of his experience[8].

Notes

[1]

Relazione finale della commissione per lo studio della

tipologia degli edifici scolastici previsti nel piano di edilizia

scolastica per il quadriennio 1972/1975, ACS

[2]

Arrighetti became a member of numerous commissions, committees and

working groups. The result would be the drafting of a final report by

the commission for the study of the typology of school buildings in the

school building plan for the four-year period 1972/1975.

[3]

See Convegno dell’Edilizia scolastica dei grandi

centri urbani, Milan 8-9-10 March 1956 cfr. Atti del

Convegno edited by Ermete Monti, Tamburini, Milan 1956

[4]

See. Exhibitions include the Mostra dell’edilizia

scolastica dei grandi centri urbani, Milan 1956 and Mostra

dell’Edilizia Scolastica, Rome 1963, Palazzo delle Esposizioni

[5]

See L’Edilizia della scuola Elementare,

Quaderni, edited by Centro Studi, Le Monnier, Florence 1960. In the

introduction, the Ministro della Pubblica Istruzione Giacinto Bosco

emphasized what was expected from these notebooks, namely «a

new, valid tool to enable the construction of school buildings that

meet the dictates of the latest pedagogy, but are also more intimately

and harmoniously sensitive to the needs of a modern school in modern

life». The nursery and primary school of twenty classrooms in

the Comasina district (pp.176-183) and the primary school of

twenty-four classrooms for the Baggio district (pp. 184-189) were

published.

[6]

The Centro Studi was set up in 1952 and was made up of architects,

pedagogues, doctors and administrators with the aim of defining the new

characteristics of school building in Italy during the reconstruction

period, seeking a close link with the principles of the modern

pedagogical approach.

[7]

See Scuola Santa Croce (1957) and its twin in Via Valvassori Peroni.

[8]

See. A.Rossi, Architettura per i musei, at IUAV,

AA:1965-1966

Bibliography

ALOI G. (1960), Scuole, Hoepli, Milano

ARRIGHETTI A. (1957), “Edilizia scolastica milanese

nel quadro urbanistico”, In: Volume in onore di

Cesare Chiodi, Giuffrè editore, Milano

ARRIGHETTI A. (1956) – “Scuola Materna a

Milano”. Edilizia Moderna, 58 (agosto)

ARRIGHETTI A. (1961) – “6 anni di

attività dell’Ufficio Studi e Progetti

Edilizi.” In: Città di Milano, Milano

BODINO C. (a cura di) (1990) – Arrigo Arrighetti

architetto, Archivio Storico Civico, Milano

CALVINO I. (1973) – Il castello dei destini

incrociati, Einaudi, Torino

CICCONCELLI C. (1958) - “Scuole Materne, elementari

e secondarie” In: CARBONARA P., Architettura

pratica, volume terzo, Composizione degli edifici. Sezione 7a

- Gli edifici per l’istruzione e la cultura,

Unione tipografico - Editrice Torinese, Torino

MINISTERO DELLA PUBBLICA ISTRUZIONE (a cura di) - Quaderni

del centro studi per l’edilizia scolastica,

L’arte della stampa, Firenze

MONTI E. (1956) - Atti del Convegno, Tamburini, Milano

ROSSI A. (1965) - “Architettura per i

musei” In: R. Bonicalzi (a cura di) Aldo Rossi.

Scritti scelti per l’architettura e la città,

Quodlibet, Fermo