Earthquakes, natural disasters, reconstruction strategies

Enrico Bordogna

Fig.

1 - Luigi Borzì, Master Plan for the reconstruction of

Messina, 1910.

Fig.

2a - Giuseppe Samonà, Palazzata di Messina, Block IX, Inps

Offices, 1956-58, view.

Fig.

2b - Giuseppe Samonà, Palazzata di Messina, Block IX, Inps

Offices, 1956-58, detail

Fig.

3 - Ludovico Quaroni, Luisa Anversa, Project of the Mother Church,

Gibellina, 1970-1972.

Fig.

4 - Franco Purini, Laura Thermes, System of Squares, Gibellina,

1982-1990.

Fig.

5a - Alvaro Siza, Roberto Collovà, Restoration and

conservation of the Mother Church, Salemi, 1982.

Fig.

5b - Alvaro Siza, Roberto Collovà, Restoration and

conservation of the Mother Church, Salemi, 1982.

Fig.

6a - Venzone, the historical center rebuilt, after the refusal of the

inhabitants to remove the rubble, in the ancient typology and with the

recovery of recognizable materials. Gianfranco Caniggia, Francesca

Sartogo, “Ricerca storico-critica per la ricostruzione e il

restauro del centro storico di Venzone”, 1977-79: analysis

tables and design scheme.

Fig.

6b - Venzone, the historical center rebuilt, after the refusal of the

inhabitants to remove the rubble, in the ancient typology and with the

recovery of recognizable materials. Gianfranco Caniggia, Francesca

Sartogo, “Ricerca storico-critica per la ricostruzione e il

restauro del centro storico di Venzone”, 1977-79: analysis

tables and design scheme.

Fig.

6c - Venzone, the historical center rebuilt, after the refusal of the

inhabitants to remove the rubble, in the ancient typology and with the

recovery of recognizable materials. Gianfranco Caniggia, Francesca

Sartogo, “Ricerca storico-critica per la ricostruzione e il

restauro del centro storico di Venzone”, 1977-79: analysis

tables and design scheme.

Fig.

7a - Luciano Semerani, Gigetta Tamaro, Osoppo Town Hall, 1978-79, in

the center reconstructed.

Fig.

7b - Luciano Semerani, Gigetta Tamaro, Osoppo Town Hall, 1978-79, in

the center reconstructed, axonometric view.

Fig.

8a - Giorgio Grassi, Agostino Renna, Recovery project of the historic

center of Teora, 1981-83: project drawings.

Fig.

8b - Giorgio Grassi, Agostino Renna, Recovery project of the historic

center of Teora, 1981-83: project drawings.

Fig.

8c - Giorgio Grassi, Agostino Renna, Recovery project of the historic

center of Teora, 1981-83: view.

Fig.

9 - Crater area of the earthquake in Central Italy, summer-autumn 2016.

Fig.

10 - Amatrice, historical center: view after the removal of the rubble,

summer 2018.

Fig.

11a - Amatrice: plan of the historic core of the Gregorian Cadastre,

first half of the 19th century.

Fig.

11b - Amatrice: the 2016 pre-earthquake regional technical map, with

the historical core, the extra-moenia expansion of the second century

and the Arnaldo Foschini complex built between 1921 and 1960.

Fig.

12a - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: plan.

Fig.

12b - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: overall model.

Fig.

12c - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: model of the central square with the

church of San Giovanni and the civic tower rebuilt by anastylosis and

the new town hall.

Fig.

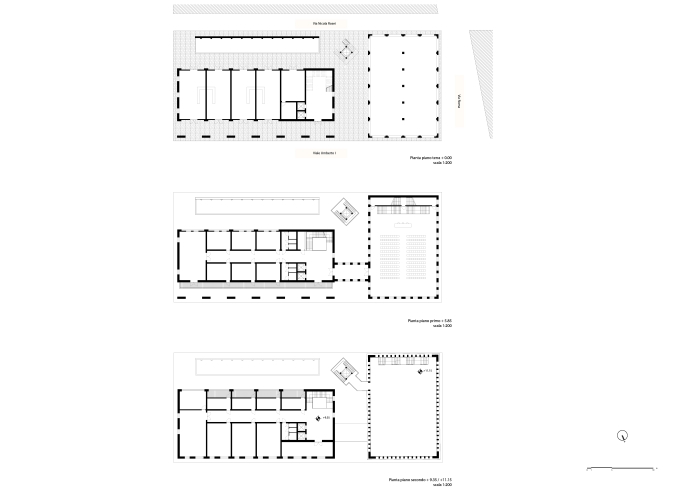

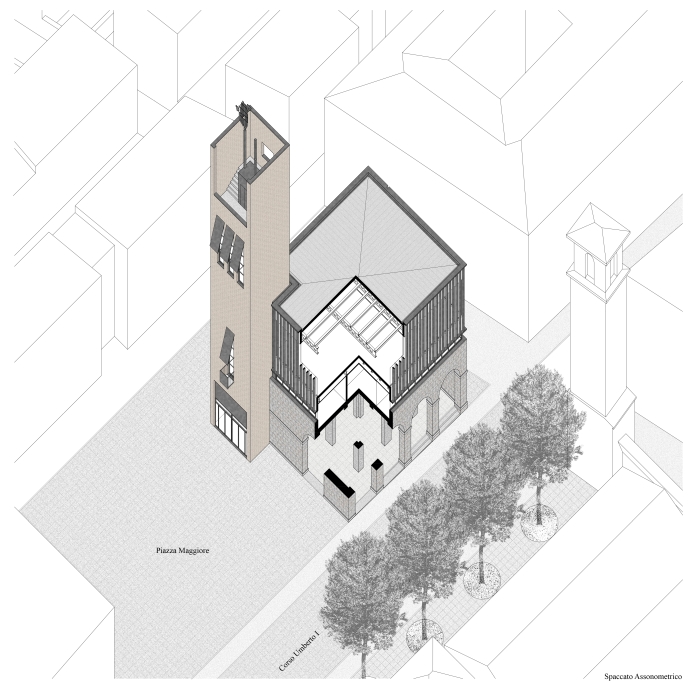

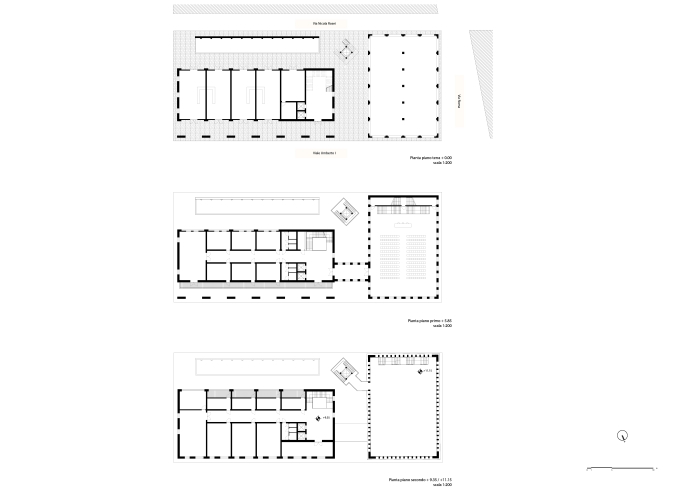

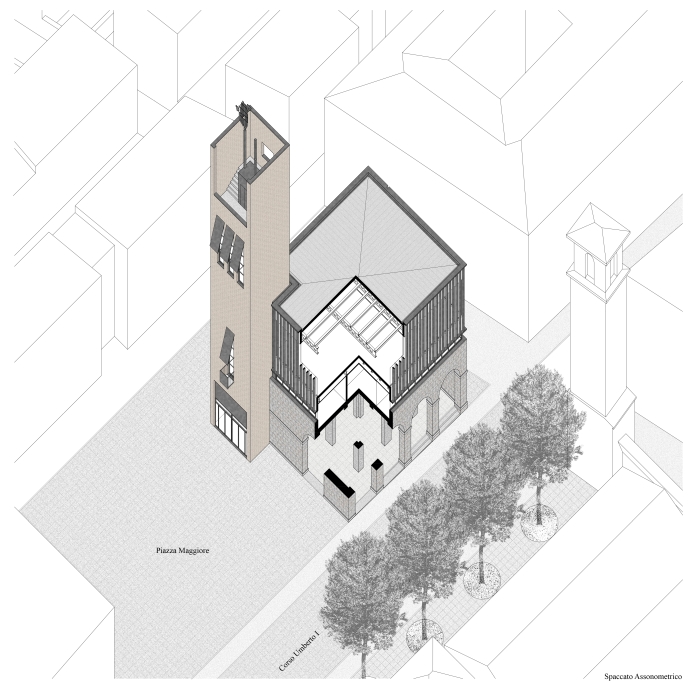

13a - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: axonometric views of the Town Hall.

Fig.

13b - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: plans of the Town Hall.

Fig.

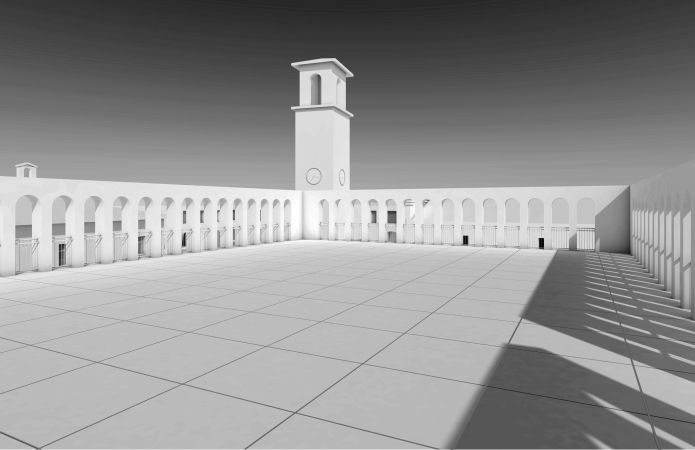

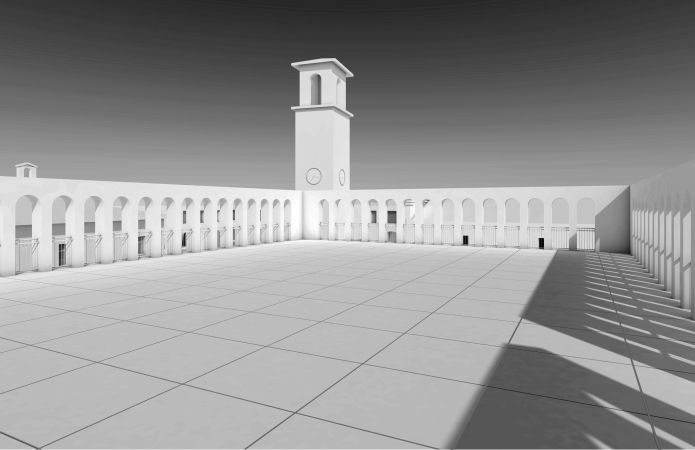

14a - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: views of the central square.

Fig.

14b - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: views of Corso Umberto.

Fig.

14c - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: views of the council chamber of the

Town Hall.

Fig.

14d - Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Reconstruction project of the

historic center of Amatrice, 2019: views of the roof-terrace of the

Town Hall.

Fig.

15a - Luca Bonardi, Andrea Valvason, “The ancient nucleus of

Amatrice: where was it, how was it?”: View of the central

square

with the church of San Giovanni and the civic tower rebuilt by

anastylosis and axonometric section of the Town Hall, Degree thesis,

Politecnico di Milano, June 2020 (supervisors E. Bordogna, T.

Brighenti).

Fig.

15a - Luca Bonardi, Andrea Valvason, “The ancient nucleus of

Amatrice: where was it, how was it?”: View of the central

square

with the church of San Giovanni and the civic tower rebuilt by

anastylosis and axonometric section of the Town Hall, Degree thesis,

Politecnico di Milano, June 2020 (supervisors E. Bordogna, T.

Brighenti).

The issues that a catastrophic event raises, whether the latter

resulted from war or was of natural origin, are many and rather complex.

Outwith the emergency phase, the issues are of a very different

stamp, yet are closely intertwined: questions of an economic nature

which concern the productive, agricultural, industrial, and commercial

bases of the context affected, along with the associated

infrastructural network; urban planning aspects, from territorial and

district levels to the municipal level, and the executive plans of

individual building sectors; more strictly architectural issues of a

morphological, typological, and formal nature, which in turn

necessarily involve problems of earthquake engineering and the stances

of restoration vs. conservation; the basic residential fabric and local

services and, at the same time, the monumental emergences and the

pattern of streets and public spaces, with their own phenomena of

damage and restoration/reconstruction needs. And behind or alongside

all of this, the associated legislative-executive and

procedural-managerial framework, with various bodies in charge of the

emergency and reconstruction phases, plus the conflict between the

prevalence of the central State or the primacy of local

self-government, the affected populations and their ad hoc

organizations.

As we can see, an almost indissoluble intertwining.

In addition, the dedicated literature also presents a comparable

complexity, as temporally vast as it is and fraught with very varied

points of view and degrees of approach, not all easily disentangled and

recomposed.

It may be easier to orient ourselves if we adopt a specific design

stance, reflecting operationally on what the reconstruction strategies

were after the main seismic events of last century and the first

decades of this century, evaluating the outcomes, the positive aspects,

and the most problematic or decidedly negative objective difficulties,

the complexities of boundary conditions, aporias, and any success

stories. And all of this starting from a concrete case, that of the

earthquake which struck Central Italy in the summer-autumn of 2016,

with this analysis being steered by the objective of elaborating

intervention, urban planning, and architectural projects, which, even

in an informed didactic experiment, must tackle the problems and

difficulties concretely, verifying possible answers as a part of the

project.

Earthquakes and reconstructions in Italy in the 1900s

Regarding the events of last century, we can begin with the Messina

earthquake of 28 December 1908. With a magnitude of 7.2, around 90,000

dead and 100,000 displaced, it struck both cities of the Strait,

Messina and Reggio Calabria, resulting in an almost total destruction

of the former. The reconstruction plan drawn up by the engineer Luigi

Borzì, dated 1910, flanked by important architectural work from

Francesco Valenti, corresponded to the pre-earthquake morphology which

dated back to the 1869 Spadaro Plan, re-proposing the same planimetric

and topographic chequerboard layout of elongated rectangular blocks,

while bringing the architectural conformation into line with the

compositional criteria, building density and contemporary construction

methods of the time. To this end, the Plan introduced precise urban

planning regulations regarding the width of the roads (a minimum of

10m) and the height of new buildings according to the section of street

they overlooked, while complying with the anti-seismic regulations

strictly imposed immediately after the disaster by special Royal

Decrees. A reconstruction which, despite conflicting opinions, was for

the most part evaluated positively, at least until the 1950s, and even

more so when compared with the betrayed city of the following decades[1].

In this line of intervention, the reconstruction of the seafront,

the historic “Palazzata” was of an emblematic value.

Beginning from an initial intervention in the 1930s by the architects

Camillo Autore and Giuseppe Samonà, the work continued in the

following decades up until the early 1960s, with the construction by

Giuseppe Samonà of 11 city blocks, characterized by the same

line of eaves and an accentuated compositional homogeneity marked by a

modern architectural approach, in some ways referable to what has been

defined “Perret-style structural classicism”, to be found

equally in the contemporary INAIL building in Venice by Samonà

and Egle Trincanato.

The case of the Belice quake in January 1968, with a series of

aftershocks continuing until February 1969, is more complex and

many-sided. With a magnitude of 6.4, around 300 deaths and 70,000

displaced persons, it hit the municipalities of the valley hard, and

with differing intensity a series of neighbouring territories in the

provinces of Agrigento, Trapani, and Palermo. Compared to the

municipalities which had virtually disintegrated, such as Gibellina,

Poggioreale, Montevago, Santa Margherita del Belice, others suffered

damage of a lesser severity, limited to single parts of the inhabited

areas or individual monumental buildings. As a result, also the kind of

reconstruction differed, with some cases of newly founded towns at a

greater or lesser distance from the pre-existing centres, designed

(mostly by the architects and urban planners of ISES, the Italian

Institute for Social Housing Development) according to architectural

and urban planning schemes based on models unrelated to local

tradition, of an abstract Nordic or Anglo-Saxon derivation, and other

cases of partial “additions”, with the reconstruction of

individual city parts or monumental complexes, alongside more measured

and meticulously designed interventions.

Among the newly founded towns, the brand-new Gibellina Nuova

certainly stands out. Rebuilt about fifteen kilometres below the

historical Gibellina, its plan based on a butterfly design is

considered not entirely successful and is arguably too sprawling,

featuring a series of terraced houses between a pedestrian street in

front and a roadway for cars behind. It is however somewhat redeemed,

thanks to the tenacious will of an enlightened mayor, Ludovico Corrao,

by a sequence of interventions of great artistic and architectural

quality. These include the piazzas of Purini and Thermes, the

architecture of the public buildings by Samonà, Quaroni,

Gregotti, Francesco Venezia, Marcella Aprile, Roberto Collovà,

the urban sculptures of Pietro Consagra, Mimmo Paladino, Fausto

Melotti, Emilio Isgrò, Nanda Vigo, Alessandro Mendini, and the

extraordinary land art masterpiece of Alberto Burri on the remains of

the devastated and abandoned historical Gibellina. Meanwhile, the

reconstruction of Poggioreale (one of those cases where the bulldozers

may have done more damage than the earthquake) has more formalistic

implications, both in its urban design and its architectural features,

with a new town built just below the ancient settlement.

The case of Salemi is different again, where Siza and

Collovà’s intervention on the Mother Church, of a great

poetic impact, marks an original line in the face of a stricken

monument, which is not that of restoration or completion through

anastylosis, but rather of an “archaeological”

conservation, after being amputated by the earthquake; a sublimated

memory and perpetuation into the future of the community value of the

maimed original.

Conflicting opinions, therefore, which, far from being

satisfactorily settled, require a differentiated and closer assessment

case by case[2].

Just a few years later, in May 1976, with repetitions in September

that same year of equal violence which definitively cancelled what had

been spared by the first shock, came the earthquake in Friuli, with a

magnitude of 6.5 on the Richter scale. This resulted in around 1,000

deaths and 45,000 displaced people and affected over 40 municipalities

declared as disaster zones, with another thirty gravely damaged in the

provinces of Udine and Pordenone, including Gemona, Venzone, Osoppo,

Majano, Artegna, Buja, and Bordano, which were among the worst affected.

The case of Friuli is considered a turning point in post-seismic

strategies. Without falling into the rhetoric of the so-called

“Friuli Model”, or the abused simplification of the slogan

“where it was, as it was”, relativized by the protagonists

of that reconstruction themselves, suffice it to recall that after that

event the Civil Defence organization [It. Protezione Civile,

t/n] took shape, both centrally and regionally, in direct contact with

the local communities involved. We should also remember the decisive

choice, vigorously desired by the population concerned, and repeated

several times but not always respected, to proceed

“bottom-up”, according to a sequence which first favoured

production, then housing, and lastly the monuments.

An exemplary case is that of Venzone. There, based on studies

carried out by Gianfranco Caniggia and Francesca Sartogo appointed

shortly after the earthquake by the Ministry of Cultural and

Environmental Heritage, the Archaeological Superintendence of Trieste

for Environmental, Architectural, Artistic and Historical Heritage of

Friuli Venezia Giulia, and the Italian Council of ICOMOS (International

Council of Monuments and Sites) to carry out historical-critical

research for the reconstruction and restoration of the historic centre

of Venzone, we can witness what is arguably the reconstruction closest

to a full-blown “where it was, as it was”. An exact

restoration of the morphological arrangement of public spaces, streets,

squares, and alignments; a rebuilding of the basic buildings of the

residential fabric in accordance with typological processes studied by

Caniggia-Sartogo and the resulting detailed plan of the Old Town by

Romeo Ballardini. With a reconstruction by anastylosis, after

meticulously collecting, cataloguing and numbering the stones left by

the earthquake belonging to the main monuments (the cathedral, town

hall, other churches, walls, towers, and town gates), and thanks also

to the studies and role of such scholars as Francesco Doglioni, the

final result is an example of a sophisticated “normality”

which is unquestionably convincing, beyond, or in any case preponderant

with respect to, the scruple of a supposed sin: the “historical

fake”[3].

If Venzone, both in the reconstruction of its urban centre and its

monuments, can be considered an emblematic example of “where it

was, as it was”, other cases of the Friulian reconstruction are

the same but in less complete terms, such as Gemona, penalized by a

consistent exodus of the population in a fragmented proliferation of

buildings below, or Osoppo, where the town hall by Luciano Semerani and

Gigetta Tamaro stands out, a happy expression, as Semerani stated, of

the will of the inhabitants, but not without “a justified

rhetoric”, to build against the violence of the earthquake

“the most beautiful and longest-lasting town hall in

Friuli”, even within an on-site reconstruction that did not

present characteristics of rigour and coherence comparable to those at

Venzone[4].

The Irpinia earthquake in November 1980, with a magnitude of 6.9 on

the Richter scale, around 1,900 deaths and 300,000 displaced persons,

affected the provinces of Avellino, Salerno, Benevento and, to a lesser

extent, Matera and Potenza. Ignoring cases like Conza or Bisaccia[5],

where the somewhat abstract modelling of certain ISES plans for Belice

seems to have re-emerged, it was the case of Teora which implemented

another possible line of “where it was, as it was”,

different if not an alternative to the Friulian one in Venzone, but

equally convincing in its desire to preserve the culture and settlement

identity of the affected area. The project by Giorgio Grassi and

Agostino Renna[6], having taken

stock of the collapses caused by the earthquake and of the areas

officially declared unfit for building purposes on the basis of

post-earthquake geological surveys, features a design which could be

described as “continuity in discontinuity”, with

interventions, typologies, and various works of architecture

differentiated by unitary parts in a direct and concrete relationship

between the old and the new: the ridge area between the castle and the

Mother Church, declared unfit for building, left as an

“archaeological” green area, with the remains of the

collapses preserved as a memory and testimony of the event; the

buildings and the fabric of the Old Town that had suffered minor damage

and were included in the areas fit for building, entirely restored

applying the principle of “where it was, as it was”

(referred to explicitly in the project report, p. 136), based on

archival documents, land registers, surveys, photographs; the monuments

of the church and castle rebuilt from scratch in situ, the

latter destined to be a residence, the Mother Church resuming the

position of the old destroyed church which, preserved as ruins, became

the churchyard of the new one; new residences concentrated in two

distinct, self-contained units (below the main street and near the

castle), characterized by a marked and essential stylistic unity so as

to make them clearly evident and recognizable as separate parts of a

strongly, programmatically unitary urban project.

Finally, the most recent reconstructions of L’Aquila (after an

earthquake in April 2009, of magnitude 5.9, with around 300 deaths and

80,000 displaced persons) and Emilia Romagna (May 2012) offer few

points of reference, given the highly questionable model for

L’Aquila, in terms of the settlement sprawl as well as

engineering, typological and architectural aspects, of the 19 villages

of the much publicized C.A.S.E. project (C.A.S.E. = Sustainable and

Eco-compatible Anti-seismic Complexes), while in Emilia the arguably

justifiable priority given to the restoration of a productive fabric

which is among the most important in Italy inopportunely legitimized

the disastrous distortion of a settlement and architectural culture of

an ancient rural tradition consolidated over the centuries, from the

days of Roman centuriation to our own times[7].

Towards a reconstruction strategy in Central Italy, 2016

If these are the indications that can be drawn from the Italian

experiences of the last century, the earthquake in Central Italy of 24

August 2016, with subsequent tremors and a seismic swarm in the autumn

of the same year – but also the following year, involved

circumstances and problems in part similar to the national case history

of the last hundred years, in part entirely specific. Moreover, it has

been observed several times and by several people that each seismic

event is a case in itself, and that to identify a reconstruction

strategy it is advisable to proceed according to a

“case-by-case” approach.

The earthquake of magnitude 6.0 and subsequently 6.5, with around

300 victims and 41,000 displaced persons, affected territories and

municipalities across four regions, The Marches, Lazio, Umbria, and

Abruzzo. This resulted in predictable difficulties from legislative,

administrative and procedural points of view to organize and manage the

interventions, not only in the emergency phase, but also in the

start-up and management of the reconstruction works with their related

general and executive plans. And this was a first element of

distinction from past experience.

Conversely, from the point of view of the settlement

characteristics, the affected territory (assuming the centres of

Amatrice, Norcia and Camerino as the most emblematic case studies and

examples of planning) presents widespread similarities with some of the

earthquake zones of the past, albeit differentiated according to the

specific internal characteristics of the individual centres concerned.

As in Friuli and Irpinia, and not very differently from Belice, in

fact, also the central-Italic crater, a vast area between the internal

Apennine ridge and the settlements sloping down towards both the

Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas, is characterized by a widespread

urbanization of towns of medieval origin, regularly walled and

clustered around a ridge, with medium-small or exceedingly small

centres, scattered across inland hilly or mountainous areas[8].

Inside the crater, however, disregarding the relative homogeneity of

the whole, with reference to Amatrice, Norcia and Camerino, the

respective economic structures are very different: that of Norcia

marked by the importance of agri-food and dairy supply chains, starting

from husbandry (especially of pigs) and agricultural crops, to the

subsequent stages of transformation, packaging, and marketing of the

related products, with a widespread network of small or even individual

artisan and commercial companies. In pole position, that of Amatrice,

oriented above all to activities related to tourism and second homes,

with the important presence of a higher education facility in the hotel

sector of supra-municipal and supra-regional importance; while

Camerino, one of the largest of the affected centres, is characterized

by the centuries-old tradition of a university town of 14th-century

origin and the allied wealth of architectural and monumental presences,

even if, in all of these centres, and in the whole area of the crater

in general, the monumental component and the charms of the landscape

are omnipresent.

The damage inflicted by the earthquake was also significantly different.

In Norcia and Camerino it was mostly concentrated in the historical

nucleus. On the whole, it was more substantial in Camerino, with the

almost complete and prolonged closure of the centre and serious damage

to several important monumental buildings such as the Town Hall and the

Cathedral; while it was more limited and circumscribed to single

sectors instead in Norcia, albeit equally serious there in single

monumental buildings such as the Cathedral. On the other hand, in both

municipalities, outside the town’s walls the damage was much more

limited or virtually non-existent.

However, both in Camerino and in Norcia, beyond their respective

differences, the residential fabric of the historical nucleus remained

intact, and although the damage had affected individual monuments and

residential sectors, the centre remained completely recognizable and

legible in its stratified urban morphology, including the houses,

streets, squares, public spaces, and monuments. And this is an

important, discriminating fact.

In contrast, Amatrice is a case all its own.

Because there the earthquake practically eliminated the historical

nucleus, of which only the ridge axis remains recognizable – the

“matrix route” to put it in Muratori/Caniggia’s

language, and little else: some sections of the churches, a part of the

civic tower, a few remnants of houses. But the residential fabric has

gone, perhaps also because, as Giovanni Carbonara lamented[9], the bulldozers and the anxiety of removal did more damage than the actual earthquake.

Nor is the damage to the urban expansion outside the walls marginal,

but what differentiates Amatrice from the other municipalities of the

crater is the clean slate of its historical nucleus, and the consequent

problem of whether and how to plan its reconstruction.

In other words, at Amatrice, the problem of reconstructing its

historical nucleus is of a theoretical rather than operational nature.

Amatrice. A reconstruction project for the ancient nucleus: where it was, as it was?

Of Frederick-Angevin origin, founded, albeit without a certain date, in the first half of the 13th

century as a garrison of the Via Salaria, a strategic military and

commercial axis since Roman times linking the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian

Seas, Amatrice has the pattern of a walled town clustered around a

ridge, with its central axis running from the north-west – where

the Castello gate used to enter from the areas of the Castellano stream

below, to the south-east – where the Church of

Sant’Agostino stands and the Carbonara gate beside it, in the

direction of a plateau extending towards the Laga mountains, the Gran

Sasso Apennines, and the Aquila basin below. Along the central axis

with an almost rectilinear course, lies an orthogonal road network,

with only two transverse axes and a grid of elongated rectangular

blocks of homogeneous dimensions.

Lying on a sort of spur between the Tronto river to the north and

the Torrente Castellano to the south, beyond the complex historical

events in the progressive passage from Swabian to Angevin dominion, and

then the Papal State with the destruction of the walls by the troops of

Charles V in 1529, and despite the frequent earthquakes and subsequent

reconstructions, what is important to note is that Amatrice has

preserved its original ridge layout with a morphology substantially

unchanged over the centuries. A morphology comparable to that of the

nearby “New Lands” of Rieti (Antrodoco, Leonessa,

Cittàducale) or of the more distant Florentine “New

Lands” such as Arnolfo di Cambio’s San Giovanni Valdarno[10].

Given the condition of a substantially clean slate as can be seen

from the photographic documentation from spring to summer of 2019, with

a few monumental buildings classified for the collection and

cataloguing of the rubble for the purposes of a conservative

philological reconstruction (essentially the churches, the civic tower

and two or three historical buildings)[11],

the choice made in some of the projects developed at the university was

firstly that of an on-site reconstruction, discarding any hypothesis of

relocation, and secondly, that of re-proposing the historical

morphology of the settlement, with the corresponding perimeter of the

former town’s walls, the axis of the ridge lying

north-west–south-east, and the morphological pattern of elongated

rectangular blocks[12].

Having made this initial choice, however, the first theoretical

problems arose: should the secondary street network respect the

historical one, with only two transverse axes not perfectly

perpendicular to the ridge axis? And should the morphology of the

blocks, with their respective access roads, respect the historical one,

meaning continuous street fronts and substantially constant lines of

eaves to mark the rectangular grid? Or, while confirming the central

ridge axis, is it possible to think of a “modern”,

rational, morphological layout, with a regularized road network and a

consequently different arrangement of the blocks? And again, dropping

down a scale, assuming the first option, should the architectural

reconstruction of the residential blocks propose faithfulness to the

pre-existing buildings also in the compositional choices and formal

aspects (heights, ways of roofing, elevations, materials, construction

systems, etc.), or opt for a “modern”, rational

reconstruction?

In other words, having stuck faithfully to the principle of

“where it was”, is that of “as it was” perhaps

not impracticable? And does it perhaps not necessarily require methods

that are contemporary, albeit respectful of the urban and architectural

forms inherited from history, not in “literal” terms, but

“substantial” terms? Though aware that the qualification

“substantial” can only fall within the sphere of the

subjective and the discretionary.

In other words (and very schematically), is Caniggia’s model

for Venzone valid? That of philological faithfulness at the risk of a

historical fake? Or is the Teora model of Grassi and Renna, of

“continuity in discontinuity” as previously observed,

better?

The two projects presented here, the result of participation in conferences and the presentations of graduation theses[13],

are concrete answers, with the absolute awareness of not wishing to be

definitive but wishing to clarify “in doing” the

theoretical and operational issues which a theme such as that of

reconstruction imposes on the planning obligation.

Two projects as experimental verification and a theoretical study

Faced with the current clean slate, both projects have assumed the

hypothesis of generally confirming the morphology inherited from the

past, retracing the perimeter of the walled town which has remained

substantially unchanged from the time of its foundation (despite the 16th-century

destruction of the walls), and introducing some – but few –

variants concerning, on the one hand, the central square, and on the

other, the conformation of the residential blocks, to configure a

hypothesis for the reconstruction which is both up-to-date and

respectful of the historical settlement while remaining rooted in the

collective memory of the population.

In particular, for the residential fabric, both projects stop at the

proposal of three typological schemes of blocks, roughly defined as

“block-style”, “terraced”,

“patio-style”, with two or three storeys above ground, to

be adopted flexibly as simple guidelines in the reconstruction process.

However, these schemes, albeit agreed on as a basic morphological choice, clearly demand further study.

The design of the central public square deserves a partially different evaluation.

In an urban environment characterized by the presence of the Church

of San Giovanni, the civic tower and the town hall, mingled with a

dense and undifferentiated fabric before the earthquake, both projects

introduce the thinning of a porticoed square straddling the course of

the ridge, in which these emergences stand out in isolation. A choice

which consciously introduces a double “infringement”: in

fact, the historical town of Amatrice, unlike the majority of the Rieti

and Florentine New Lands, did not have a central public square with the

monumental emergences of civil and religious power; in addition to

which, the typology of the portico and the porticoed urban

thoroughfare, was alien to its urban history. Nevertheless, for the

undersigned, both projects seem convincing in this choice, as does the

decision to resort, for the town hall, to the historical typology of

the “broletto”, or mercantile loggia, open on all

four sides, with an entirely porticoed ground floor and an upper floor

free from intermediate pillars for a public council chamber/civic hall

for exhibitions, conferences, shows (in reality, according to the

canonical model of the broletto, both projects indulge in

some poetic licence: the first by providing an entirely terraced roof

for outdoor parties and events; the second by inserting an intermediate

floor for offices and administrative functions between the restored

porticoed base and the hall).

On the other hand, the two projects do differ in their individual

compositional and language choices, in a different relationship between

new and old: the first is more assonant, with a declared reference to a

Muzio-like figuration; the second more marked and up-to-date, in a

determination to clearly detach the old of the restored porticoed base

with respect to the new in the volume above, and in the insertion of a

“modern” medieval tower with explicit formal references,

functioning not only as ascent staircase/fire escape, but also as a

lookout point for observation of the town from above.

In conclusion, it is worth recalling the experimental nature of

these analyses and projects, given the complexity of the issues

involved in the theme of reconstruction recalled at the start of this

essay. In particular, with respect to the justified distrust of many

restoration specialists regarding the deceptive simplification of the

formula “where it was, as it was”, the doubt that the

examples of reconstruction analysed (in particular Venzone, Teora, and

Messina), which our own projects raise, as to whether this reserve

applies equally to the edifices and monumental areas of the town as it

does to the more basic buildings and the traditional housing fabric, or

if the criteria and methods of an intervention should not be fittingly

differentiated according to the specific remit of the architectural

project.

And this in compliance with the belief, as has been said, that the

reconstruction of a town or city is never a merely physical fact, of

infrastructure, buildings, communal urban spaces, services, and

greenery. Is not an exclusively urban and architectural work. But is

the reconstruction of a community.

Notes

[1]In the copious bibliography, for the different evaluations, see at least: Giuseppe Miano, Il Piano Borzì, in Giusi Currò, La trama della ricostruzione. Messina dalla città dell’Ottocento alla ricostruzione dopo il sisma del 1908, Gangemi, Rome 1991, pp. 47-61; Francesco Cardullo, La ricostruzione di Messina 1909-1940: l’architettura dei servizi pubblici e la città, Officina, Rome 1993; Francesco Cardullo, Giuseppe e Alberto Samonà e la Metropoli dello Stretto di Messina, Officina, Rome 2006; Francesco Cardullo, La ricostruzione di Messina: tra piani, case e ingegneri, in Vv.Aa., edited by Giuseppe Campione, La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI) 2009, pp. 81-96; Nicola Aricò, Ragionamento sulla città tradita, idem, pp. 317-328; Francesco Indovina, Messina: natura, guerra e speculazione, idem, pp. 337-350.

On the general theme of reconstruction strategies, see the special

monographic issue of the journal “Hinterland”, nos. 5-6

from 1978, dedicated to natural disasters and reconstruction

strategies, and the editorial by Guido Canella Assumere l’emergenza che non finisce, pp. 2-3.

[2]Amid the vast bibliography, for an overview, see at least: Eirene Sbriziolo de Felice, Belice 1968. Decennale di un terremoto: promemoria per soli architetti?, with the annexed Schede by Sergio Bracco, in “Hinterland”, nos. 5-6, 1978, pp. 16-23; Agostino Renna, Antonio De Bonis, Giuseppe Gangemi, Costruzione e progetto. La Valle del Belice, Clup, Milan 1979; Luca Ortelli, Architettura di muri. Il museo di Gibellina di Francesco Venezia, in “Lotus International”, no. 42, 1984, pp. 120-128; Marcella Aprile, Roberto Collovà, Teresa La Rocca, Ricostruzione delle Case Di Stefano, Gibellina, in “Domus”, no. 718, 1990, pp. 33-43; Pierluigi Nicolin, Una via porticata. Franco Purini e Laura Thermes a Gibellina, in “Lotus International”, no. 69, 1991, pp. 90-102; Giuseppe Marinoni, Metamorfosi del centro urbano. Il caso di Gibellina, idem, pp. 72-89; Alvaro Siza Vieira, Roberto Collovà, Ricostruzione della Chiesa Madre e ridisegno della piazza Alicia e delle strade adiacenti, Salemi, Trapani, in “Domus”, no. 813, 1999; Alvaro Siza Vieira, Roberto Collovà, Atti minimi nel tessuto storico, Salemi, 1991-1998, in “Lotus International”, 106, 2000, pp. 104-109; Marcella Aprile, Il terremoto del Belice o del fraintendimento, in Vv.Aa., edited by Giuseppe Campione, La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI) 2009, pp. 221-234; Franco Purini, Un’esperienza siciliana, idem, pp. 235-240; Roberto Collovà, Belice fermo immagine 2018. Le qualità resistenti della ricostruzione, in Vv.Aa., Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni, edited by Alberto Ferlenga and Nina Bassoli, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI) 2018, pp. 77-82.

[3]Also in this case, among the very rich bibliography it is worth mentioning: Gianfranco Caniggia, Francesca Sartogo, Ricerca storico-critica per la ricostruzione e il restauro del centro storico di Venzone, ICOMOS-Consiglio Italiano, 1977-1979; Gianugo Polesello, Friuli 1976. Riedificare per un contesto senza città, with the annexed Schede by Giusa Marcialis and Pierluigi Grandinetti, in “Hinterland”, nos. 5-6, 1978, pp. 42-55; Luciano Semerani, Vajont 1963. Ricostruzione senza rinascita, with the annexed Schede and an interview Longarone: un sindaco quindici anni dopo, in “Hinterland”, nos. 5-6, 1978, pp. 4-15; Paolo Marconi, Restauro e conservazione: com’era, dov’era?, in “Zodiac”, no. 19, 1998, pp. 40-55; Francesca Sartogo, Udine e Venzone. Lettura critica per una storia operante del territorio friulano, Alinea, Florence 2008; Alessandro Camiz, Venzone, una città ricostruita (quasi) “dov’era, com’era”, in “Paesaggio Urbano”, no. 5/6, 2012, pp. 18-25; Alessandro Camiz, New towns o ricostruzione (quasi) “dov’era, com’era”? L’esempio del progetto per Venzone, in “Urbanistica Dossier”, no. 005, 2013, pp. 85-89; Marisa Dalai Emiliani, Venzone “com’era e dov’era”: da eresia a modello, in Corrado Azzollini, Giovanni Carbonara (eds.), Ricostruire la memoria. Il patrimonio culturale del Friuli a quarant’anni dal terremoto, Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese, Udine 2016, pp. 85-93; Remo Cacitti, Francesco Doglioni, Il Duomo di Venzone, idem, pp. 104-115; Corrado Azzollini, Antonio Giusa (eds.), Memorie. Arte, immagini e parole del terremoto in Friuli,

catalogue of an exhibition at Villa Manin, Azienda Speciale Villa Manin

– Skira editore, Milan 2016; Francesco Doglioni, Friuli 1976. Venzone com’era e dov’era, in Vv.Aa., Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni,

edited by Alberto Ferlenga and Nina Bassoli, Silvana Editoriale,

Cinisello Balsamo, Milan 2018, pp. 83-91. With regard to the question

of the “historical fake”, see the numerous interventions by

Marco Dezzi Bardeschi, where the combination of “where it was, as

it was” announces a “naive self-deception”, a

“captivating misunderstanding”, a “big hoax that dies

hard”, aimed at soothing behind an “analogical scenographic

reconstruction “the dramatic trauma of a population struck in its

centuries-old places of life and affection”, in Marco Dezzi

Bardeschi, L’ora della prevenzione, in

“Ananke”, no. 79, September 2016, pp. 3-4. On the same

topics, see also the previous issues of Dezzi’s magazine, issues

no. 42, June 2004, and no. 3, December 1993, with numerous

interventions by Dezzi himself and by such important scholars as

Giovanni Carbonara, Roberto Cecchi, Luigia Binda, Stefano Della Torre,

Carolina Di Biase, Antonio Acuto, and others.

[4] See: Giovanni Pietro Nimis, La ricostruzione possibile. La ricostruzione nel centro storico di Gemona del Friuli dopo il terremoto del 1976, with a preface by Francesco Tentori, Marsilio, Venice 1988; Giovanni Pietro Nimis, Terre mobili. Dal Belice al Friuli, dall’Umbria all’Abruzzo, Donzelli, Rome 2009; Luciano Semerani, Architetture, in Composizione, progettazione, costruzione, edited by Enrico Bordogna, Laterza, Bari 1999, pp. 59-105.

[5] Annarita Teodosio, Oltre le macerie. Ricostruzione in Irpinia tra antichi luoghi e nuovi spazi, in “Urbanistica Dossier”, no. 005, 2013, pp. 98-101; Filippo Orsini, Irpinia 1980. Un terremoto dimenticato, in Vv.Aa., Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni, edited by Alberto Ferlenga and Nina Bassoli, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI) 2018, pp. 92-97.

[6] Among the various essays by Giorgio Grassi and Agostino Renna on the topic, see in particular: Giorgio Grassi, Agostino Renna, Piano di recupero del centro storico di Teora (Avellino), 1981, in Giorgio Grassi, I progetti, le opere e gli scritti, Electa, Milan 1996, pp. 128-141. See also Riccardo Campagnola, Ri-comporre

l’infranto: figure di rifondazione. Tesi e ipotesi sul Progetto

di ricostruzione del centro storico di Teora (Avellino) di Giorgio

Grassi, in M.G. Eccheli, A. Pireddu (ed.), Oltre l’Apocalisse, Firenze University Press, Florence 2016, pp. 24-39.

[7] For L’Aquila, see: L’Aquila.

Il Progetto C.A.S.E., Complessi Antisismici Sostenibili ed

Ecocompatibili. Un progetto di ricostruzione unico al mondo che ha

consentito di dare alloggio a quindicimila persone in soli nove mesi, a creation of Gian Michele Calvi, edited by Roberto Turino, IUSS, Pavia 2010. For Emilia Romagna, see: Matteo Agnoletto, Emilia 2012. La fine di una storia, in Vv.Aa., Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni, edited by Alberto Ferlenga and Nina Bassoli, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo, Milan 2018, pp. 128-129; Massimo Ferrari, Emilia 2012. Territorio sovrainciso, idem, pp.123-127.

[8]According to ISTAT surveys

on 31 December of the years 2010, 2016, 2019, the resident population

in the three municipalities in question was: Amatrice 2717, 2532, 2358;

Norcia 4995, 4981, 4724; Camerino 7130, 7007, 6692.

[9] See Giovanni Carbonara, Conference: La ricostruzione e l’identità dei luoghi, as a part of the study course Beni culturali ed emergenza

of the National council of Architects, Planners, Landscape Architects

and Conservators, held at the CNAPPC HQ in Rome on 24 January 2020.

[10]On the urban history of Amatrice, among the extensive bibliography, see: Giovanni Carbonara, Gli insediamenti degli ordini mendicanti in Sabina, in Lo spazio dell’umiltà, Atti del Convegno, Fara Sabina 1984; Marina Righetti Tosti-Croce (ed.), La Sabina Medievale, Amilcare Pizzi, Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti, Rieti 1985; Enrico Guidoni, L’espansione urbanistica di Rieti nel XIII secolo e le città di nuova fondazione angioina, in La Sabina Medievale, op. cit.; Luigi Aquilini, Carlo V, Alessandro Vitelli, il Feudo di Amatrice, S.E., Milan 1999; Luigi Aquilini, Carlo Blasetti, Amatrice: dagli angioini agli aragonesi. Monografia storico-araldica di un antico comune, Aniballi Grafiche, Ancona 2004; Romeo Giammarini, L’impianto urbano della città di Amatrice. Geometrie, adattamenti e trasformazioni secc. XIII-XV, in “Storia dell’Urbanistica”, no. 9/2017, Centri di fondazione e insediamenti urbani nel Lazio (XII-XX secolo): da Amatrice a Colleferro, Edizioni Kappa, Rome 2017; Anna Imponente, Rossana Torlontano, Amatrice. Forme e immagini del territorio, Electa, Milan 2015; Alessandro Viscogliosi, Amatrice. Storia, arte, cultura,

Fondazione Dino ed Ernesta Santarelli, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello

Balsamo (MI) 2016. For San Giovanni Valdarno and the Florentine New

Lands, see Edoardo Detti, Gian Franco Di Pietro, Giovanni Fanelli, Città murate e sviluppo contemporaneo, Edizioni CISCU, Lucca 1968.

[11]See the Inspection Report

of the Technical Verification Group of the Civil Defence and

Municipality of Amatrice of March 2019, which includes differentiated

operations: dismantling and cataloguing of certain monumental

buildings; securing the few buildings with limited damage; demolition

and removal of the rubble of the remaining built fabric.

[12] See: Architectural Design Workshop, two-year Master’s Degree in the “Architecture and Urban Design” [Architettura e Disegno Urbano]

study course, Polytechnic University of Milan, supervisors Enrico

Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, AY 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20.

During these years, in addition to the annual or six-monthly exams,

various degree theses concerning Amatrice, Norcia, Camerino were

produced. In October 2017, a first inspection was carried out on the

occasion of participation as speakers at the 1997-2017 Conference. Strategie per la ricostruzione post-sisma,

edited by Luigi Coccia and Marco D’Annuntiis, School of

Architecture and Design, University of Camerino, Ascoli Piceno, 26

October 2017. A second inspection was carried out on 5-7 May 2019.

[13] See: Enrico Bordogna, Tommaso Brighenti, Progetto di ricostruzione del centro di Amatrice: com’era, dov’era?, in collaboration with A. Bonardi, A. Valvason; students L. Martellini, N. Mawed, M. Polvani, G. Rosso, presented at the 17th Convention Identità dell’architettura italiana, Florence, 11-12 December 2019; Andrea Bonardi, Andrea Valavason, Il nucleo antico di Amatrice: dov’era, com’era?, Degree Thesis at the Polytechnic University of Milan, June 2020 (supervisors E. Bordogna, T. Brighenti).

References

AGNOLETTO M. (2018) – “Emilia 2012. La fine di una storia”. In: FERLENGA A. and BASSOLI N. (eds.), Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 128-129.

AQUILINI L. (1999) - Carlo V, Alessandro Vitelli, il Feudo di Amatrice. S.E., Milan.

AQUILINI L. and BLASETTI C. (2004) - Amatrice: dagli angioini agli aragonesi. Monografia storico-araldica di un antico comune. Aniballi Grafiche, Ancona.

APRILE M., COLLOVÀ R. and LA ROCCA T. (1990) – “Ricostruzione delle Case Di Stefano, Gibellina”. Domus, 718, pp. 33-43.

APRILE M. (2009) – “Il terremoto del Belice o del fraintendimento”. In: Vv.Aa., CAMPIONE G. (ed.), La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 221-234.

ARICÒ N. (2009) – “Ragionamento sulla città tradita”. In: Vv.Aa., CAMPIONE G. (editor), La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 317-328.

AZZOLLINI C. and GIUSA A. (eds.) (2016) - Memorie. Arte, immagini e parole del terremoto in Friuli, catalogue of an exhibition at Villa Manin. Azienda Speciale Villa Manin – Skira editore, Milan.

CACITTI R. and DOGLIONI F. (2016) – “Il Duomo di Venzone”. In: AZZOLLINI C. and CARBONARA G. (eds.), Ricostruire la memoria. Il patrimonio culturale del Friuli a quarant’anni dal terremoto. Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese, Udine, pp. 104-115.

CALVI G.M. (2010) - L’Aquila. Il Progetto C.A.S.E., Complessi

Antisismici Sostenibili ed Ecocompatibili. Un progetto di ricostruzione

unico al mondo che ha consentito di dare alloggio a quindicimila

persone in soli nove mesi. IUSS, Pavia.

CAMIZ A. (2012) – “Venzone, una città ricostruita

(quasi) ‘dov’era, com’era’”. Paesaggio

Urbano, 5/6, pp. 18-25.

CAMIZ A. (2013) – “New towns o ricostruzione (quasi) “dov’era,

com’era”? L’esempio del progetto per Venzone”. Urbanistica Dossier,

005, pp. 85-89.

CAMPAGNOLA R. (2016) – “Ri-comporre l’infranto: figure di

rifondazione. Tesi e ipotesi sul Progetto di ricostruzione del centro

storico di Teora (Avellino) di Giorgio Grassi”. In: ECCHELI M.G. and

PIREDDU A. (eds.), Oltre l’Apocalisse. Firenze University Press, Florence, pp. 24-39.

CANELLA G. (1978) – “Assumere l’emergenza che non finisce”. Calamità naturali e strategie di ricostruzione (numero monografico) Hinterland, 5-6 (September-December), 2-3.

CANIGGIA G. and SARTOGO F. (1977-1979) - Ricerca storico-critica per la ricostruzione e il restauro del centro storico di Venzone. ICOMOS-Consiglio Italiano.

CARBONARA G. (1984) – “Gli insediamenti degli ordini mendicanti in Sabina”. In Lo spazio dell’umiltà. Atti del Convegno, Fara Sabina.

CARDULLO F. (1993) - La ricostruzione di Messina 1909-1940: l’architettura dei servizi pubblici e la città. Officina, Rome.

CARDULLO F. (2006) - Giuseppe e Alberto Samonà e la Metropoli dello Stretto di Messina. Officina, Rome.

CARDULLO F. (2009) – “La ricostruzione di Messina: tra

piani, case e ingegneri”. In: Vv.Aa., Campione G. (ed.), La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 81-96.

COLLOVÀ R. (2018) – “Belice fermo immagine 2018. Le qualità

resistenti della ricostruzione”. In: Ferlenga A. and Bassoli N. (eds.),

Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 77-82.

DALAI EMILIANI M. (2016) – “Venzone “com’era

e dov’era”: da eresia a modello”. In: AZZOLLINI C.

and CARBONARA G. (eds.), Ricostruire la memoria. Il patrimonio culturale del Friuli a quarant’anni dal terremoto. Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese, Udine, pp. 85-93.

DETTI E., DI PIETRO G. F. and FANELLI G. (1968) – Città murate e sviluppo contemporaneo. Edizioni CISCU, Lucca.

DEZZI BARDESCHI M. (2016) – “L’ora della prevenzione”. Ananke, 79, (September), pp. 3-4.

DOGLIONI F. (2018) – “Friuli 1976. Venzone com’era

e dov’era”. In: FERLENGA A. and BASSOLI N. (eds.), Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 83-91.

FERRARI M. (2018) – “Emilia 2012. Territorio sovrainciso”. In: FERLENGA A. and BASSOLI N. (eds.), Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp.123-127.

GIAMMARINI R. (2017) - “L’impianto urbano della città di Amatrice.

Geometrie, adattamenti e trasformazioni secc. XIII-XV”. Storia

dell’Urbanistica, 9/2017, Centri di fondazione e insediamenti urbani nel Lazio (XII-XX secolo): da Amatrice a Colleferro.

GRASSI G. and RENNA A. (1996) – “Piano di recupero del

centro storico di Teora (Avellino), 1981”. In: Grassi G., I progetti, le opere e gli scritti. Electa, Milan, pp. 128-141.

GUIDONI E. (1985) – “L’espansione urbanistica di Rieti nel XIII

secolo e le città nuove di fondazione Angioina”. In: RIGHETTI

TOSTI-CROCE M. (ed.), La Sabina Medievale., Amilcare Pizzi Editore, Cassa di Risparmio di Rieti, Rieti, pp. 166-187.

IMPONENTE A. and TORLONTANO R. (2015) - Amatrice. Forme e immagini del territorio. Electa, Milan.

INDOVINA F. (2009), “Messina: natura, guerra e speculazione”. In: Vv.Aa., Campione G. (editor), La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 337-350.

MARCONI P. (1998) – “Restauro e conservazione: com’era, dov’era?”. Zodiac, 19, pp.40-55.

MARINONI G. (1991) – “Metamorfosi del centro urbano. Il caso di Gibellina”. Lotus International, 69, pp. 72-89.

MIANO G. (1991) – “Il Piano Borzì”. In: CURRÒ G., La trama della ricostruzione. Messina dalla città dell’Ottocento alla ricostruzione dopo il sisma del 1908. Gangemi, Rome, pp. 47-61.

NICOLIN P. (1991) – “Una via porticata. Franco Purini e Laura Thermes a Gibellina”. Lotus International, 69, pp. 90-102.

NIMIS G.P. (1988) - La ricostruzione possibile. La ricostruzione nel centro storico di Gemona del Friuli dopo il terremoto del 1976, with a preface by Tentori F. Marsilio, Venice.

NIMIS G.P. (2009) - Terre mobili. Dal Belice al Friuli, dall’Umbria all’Abruzzo. Donzelli, Rome.

ORSINI F. (2018) – “Irpinia 1980. Un terremoto dimenticato”. In: FERLENGA A. and BASSOLI N. (eds.), Ricostruzioni. Architettura, città, paesaggio nell’epoca delle distruzioni. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 92-97.

ORTELLI L. (1984) – “Architettura di muri. Il museo di Gibellina di Francesco Venezia”. Lotus International, 42, pp. 120-128.

POLESELLO G. (1978) – “Friuli 1976. Riedificare per un contesto senza città” (with the annexed Schede by Giusa Marcialis and Pierluigi Grandinetti). Hinterland, 5-6, pp. 42-55.

PURINI F. (2009) – “Un’esperienza siciliana”. In: Vv.Aa., CAMPIONE G. (ed.), La furia di Poseidon. Messina 1908 e dintorni, 2 vols., vol. 2. Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), pp. 235-240.

RENNA A., DE BONIS A. e GANGEMI G. (1979) - Costruzione e progetto. La Valle del Belice. Clup, Milan.

SARTOGO F. (2008) – Udine e Venzone. Lettura critica per una storia operante del territorio friulano. Alinea, Florence.

SBRIZIOLO DE FELICE E. (1978) – “Belice 1968. Decennale

di un terremoto: promemoria per soli architetti?” (with the

annexed Schede by Sergio Bracco). Hinterland, nos. 5-6, pp. 16-23.

SEMERANI L. (1999) – “Architetture”. In: Composizione, progettazione, costruzione, BORDOGNA E. (ed.). Laterza, Bari, pp. 59-105.

SEMERANI L. (1978) – “Vajont 1963. Ricostruzione senza rinascita” (with the annexed Schede e l’intervista Longarone: un sindaco quindici anni dopo). Hinterland, 5-6, pp. 4-15.

SIZA VIEIRA A. and COLLOVÀ R. (1999) – “Ricostruzione della Chiesa

Madre e ridisegno della piazza Alicia e delle strade adiacenti, Salemi,

Trapani”. Domus, 813.

SIZA VIEIRA A. and COLLOVÀ R. (2000) – “Atti minimi nel tessuto storico, Salemi, 1991-1998”. Lotus International, 106, pp. 104-109.

TEODOSIO A. (2013) – “Oltre le macerie. Ricostruzione in Irpinia tra

antichi luoghi e nuovi spazi”. Urbanistica Dossier, 005, pp. 98-101.

VISCOGLIOSI A. (2016) - Amatrice. Storia, arte, cultura. Fondazione Dino ed Ernesta Santarelli, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI).