Fig. 1 -

Cover of the number 1 of the new series of «Zodiac», February 1989..

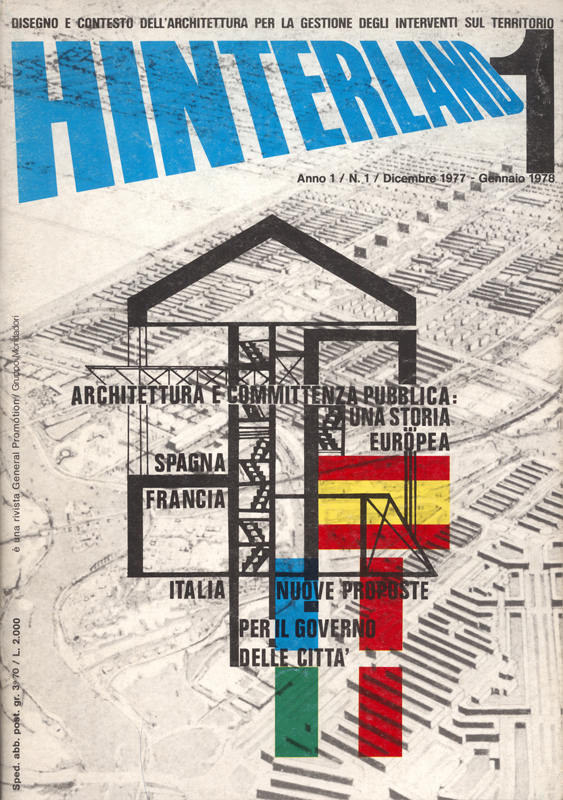

Fig. 2 - Cover of the number 1 of «Hinterland», December 1977-January 1978, dedicated to Architecture and public commissioning: a European history.

Fig. 2 - Cover of the number 1 of «Hinterland», December 1977-January 1978, dedicated to Architecture and public commissioning: a European history.

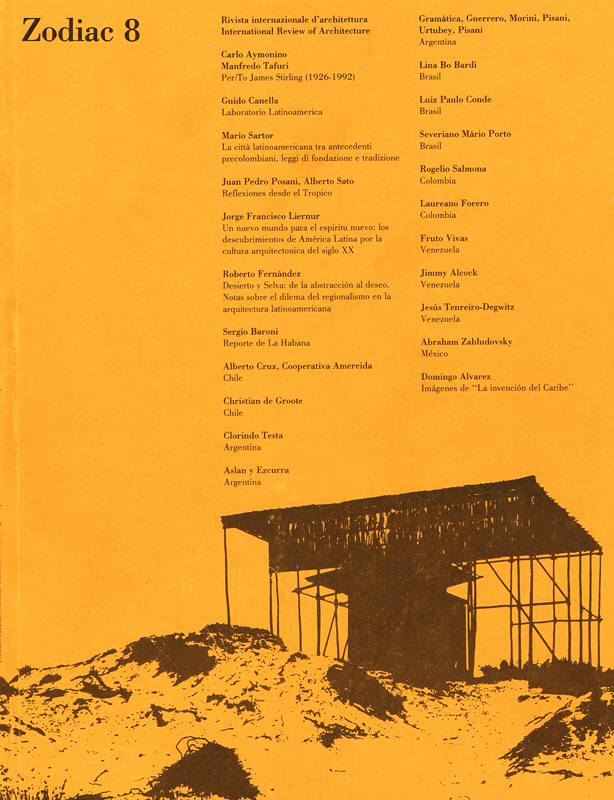

Fig. 3 - Cover of the number 8 of «Zodiac», n.s., October 1992, dedicated to the The Latin American Laboratory.

Fig. 4 - Cover of the number 11 of «Zodiac», n.s., March 1994, dedicated to Architecture in California.

Fig. 4 - Cover of the number 11 of «Zodiac», n.s., March 1994, dedicated to Architecture in California.

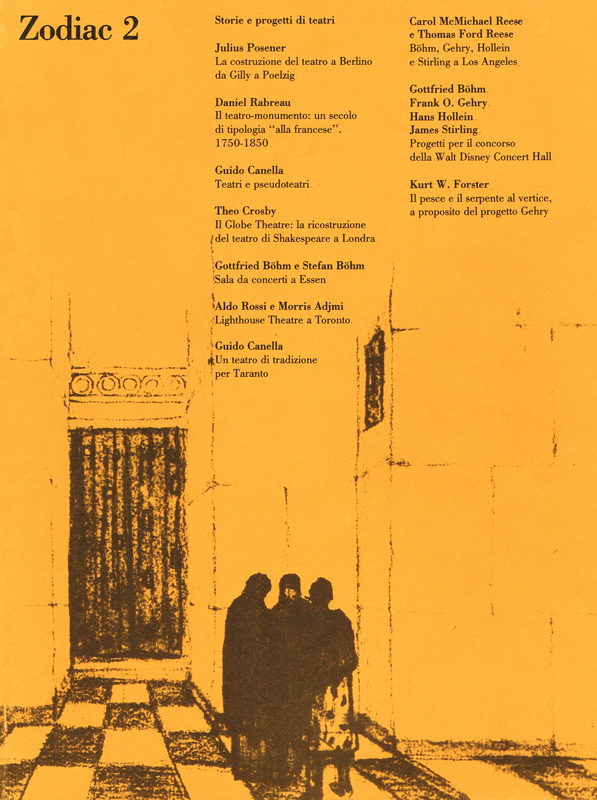

Fig. 5 - Cover of the number 2 of «Zodiac», n.s., September 1989, dedicated to Theatre history and design.

Fig. 6 - Cover of the number 6 of «Zodiac», n.s., October 1991, dedicated to Su certain deviations from museum archetype.

Fig. 6 - Cover of the number 6 of «Zodiac», n.s., October 1991, dedicated to Su certain deviations from museum archetype.

Fig. 7 - Cover of the number 7 of «Zodiac», n.s., April 1992, dedicated to the University and the city.

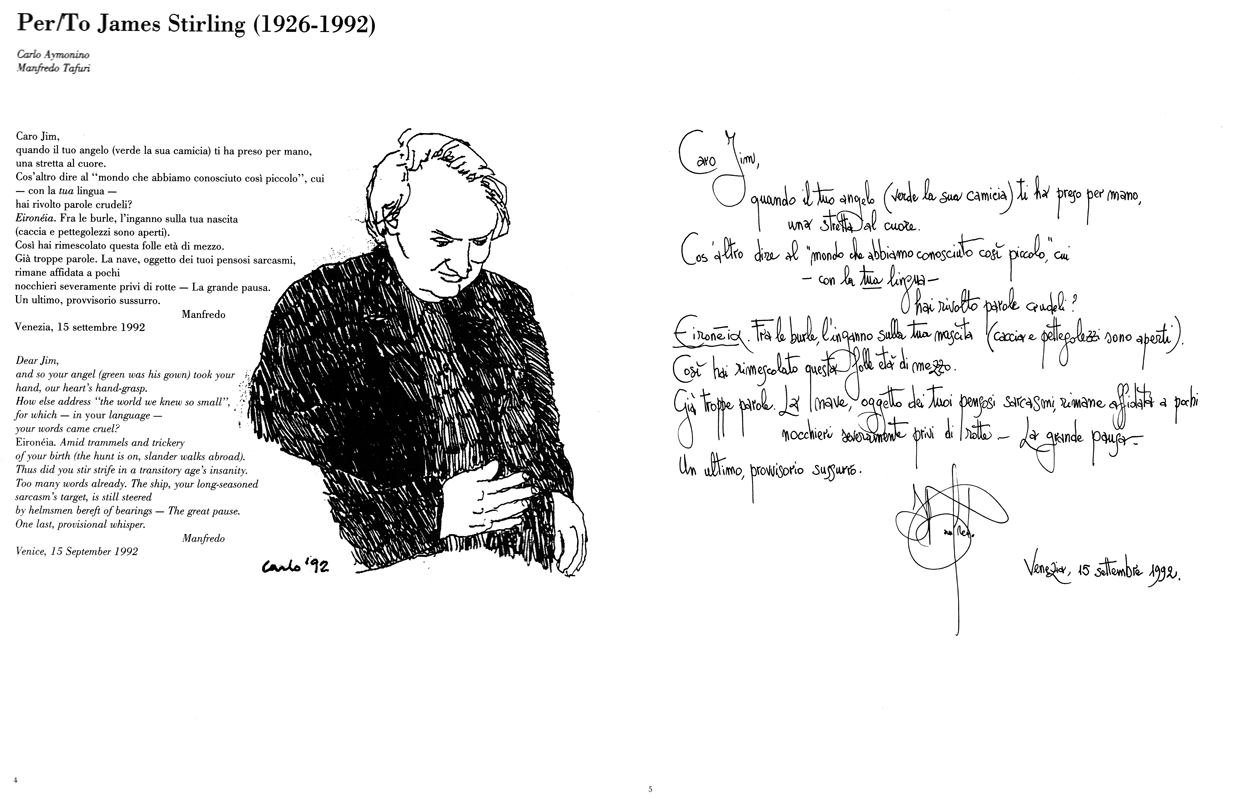

Fig. 8 - Testimony for James Stirling by Carlo Aymonino and Manfredo Tafuri, in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 8, October 1992, pp- 4-5.

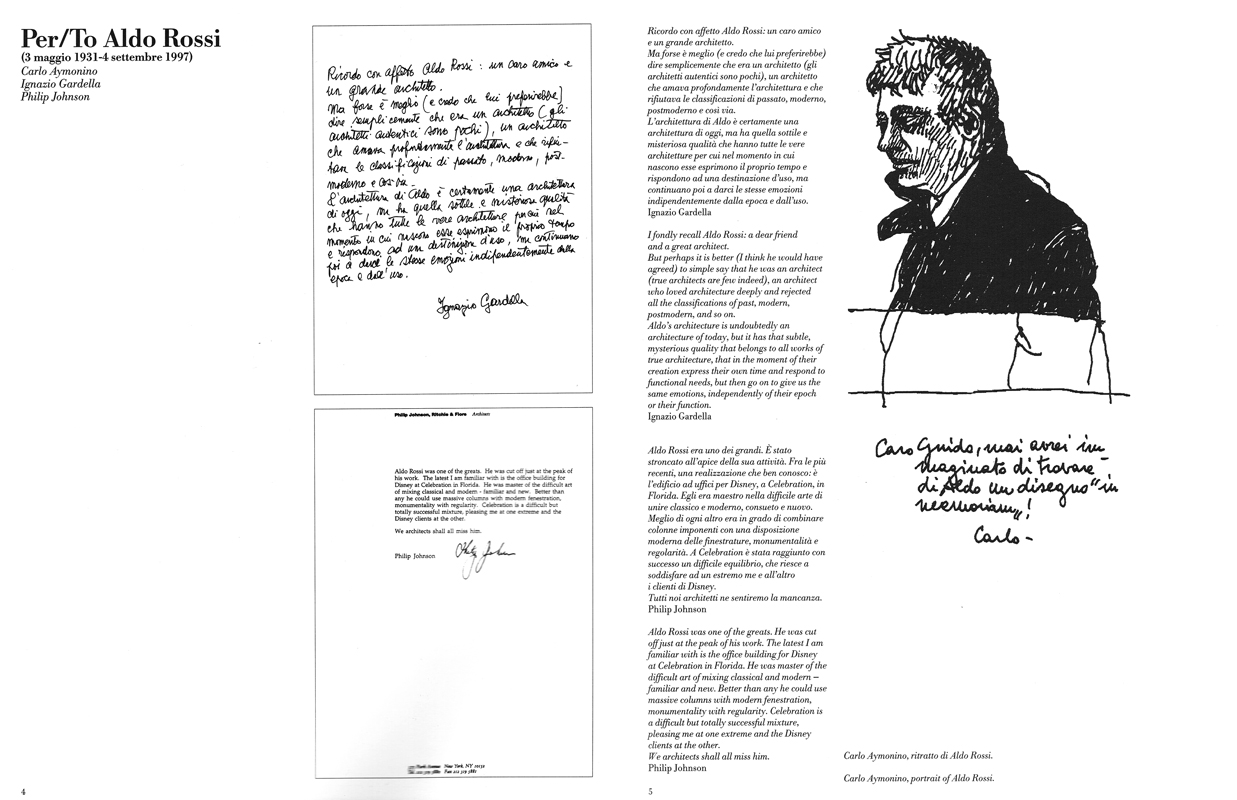

Fig. 9 - Testimony

for Aldo Rossi by Carlo Aymonino, Ignazio Gardella and Philip Johnson,

in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 18, November 1997, pp- 4-5.

Fig.

10 - Initial pages of the essay by Julius Posener Theater construction

in Berlin from Gilly to Poelzig, in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 2,

September 1989, pp- 6-7.

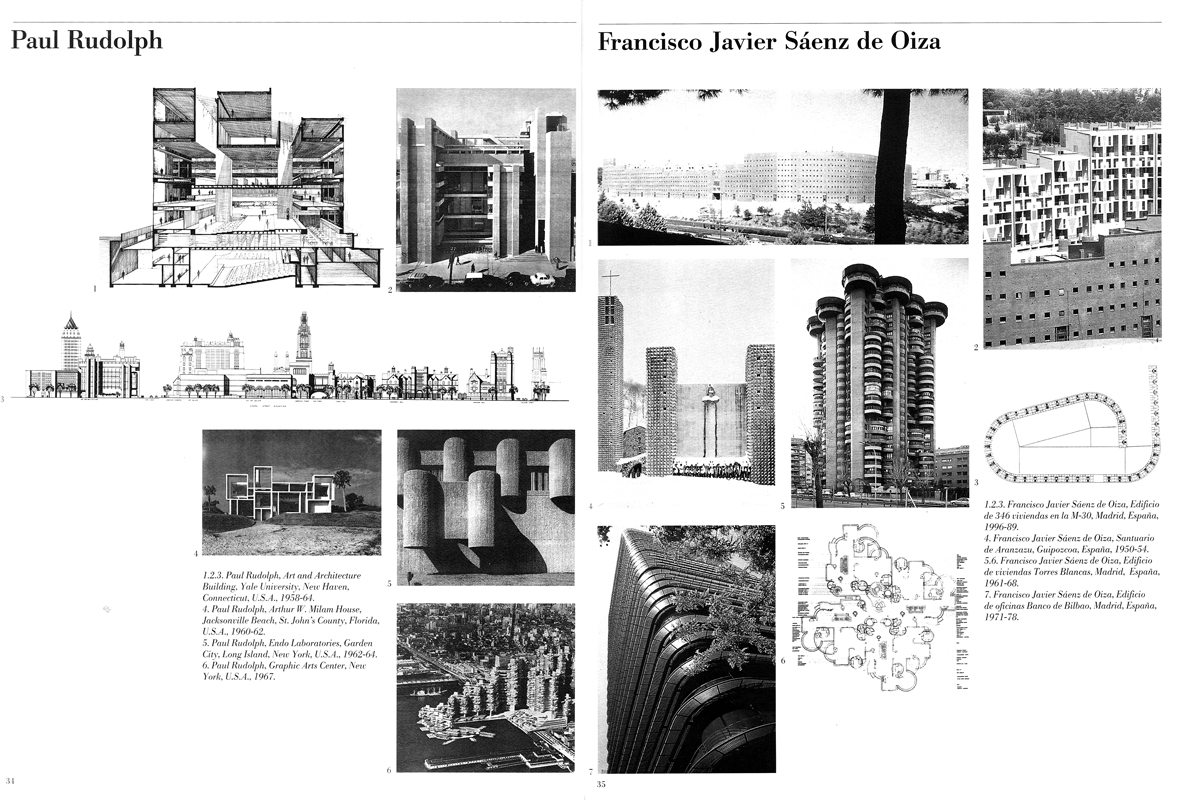

Fig. 11 - Two

pages of regesto in the issue dedicated to the generation of architects

born around 1920, in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 16, November 1996,

pp- 34-35.

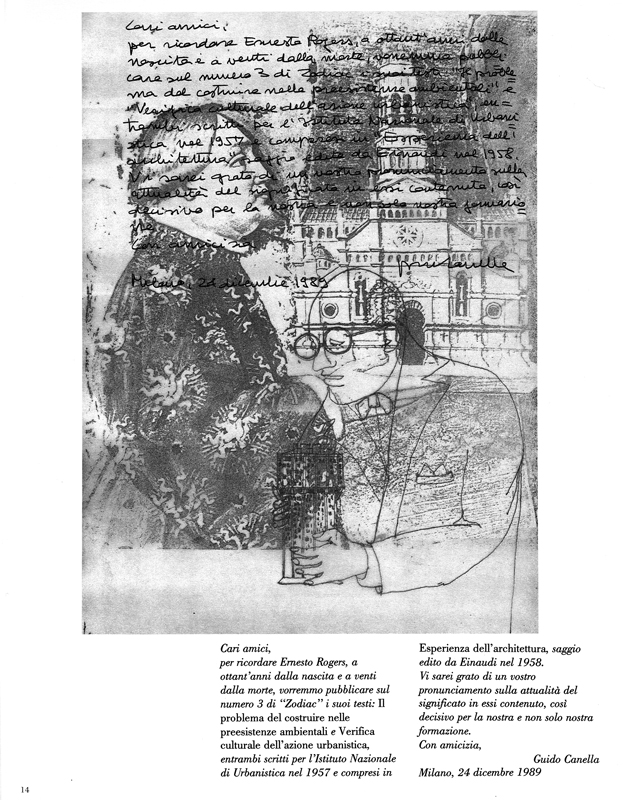

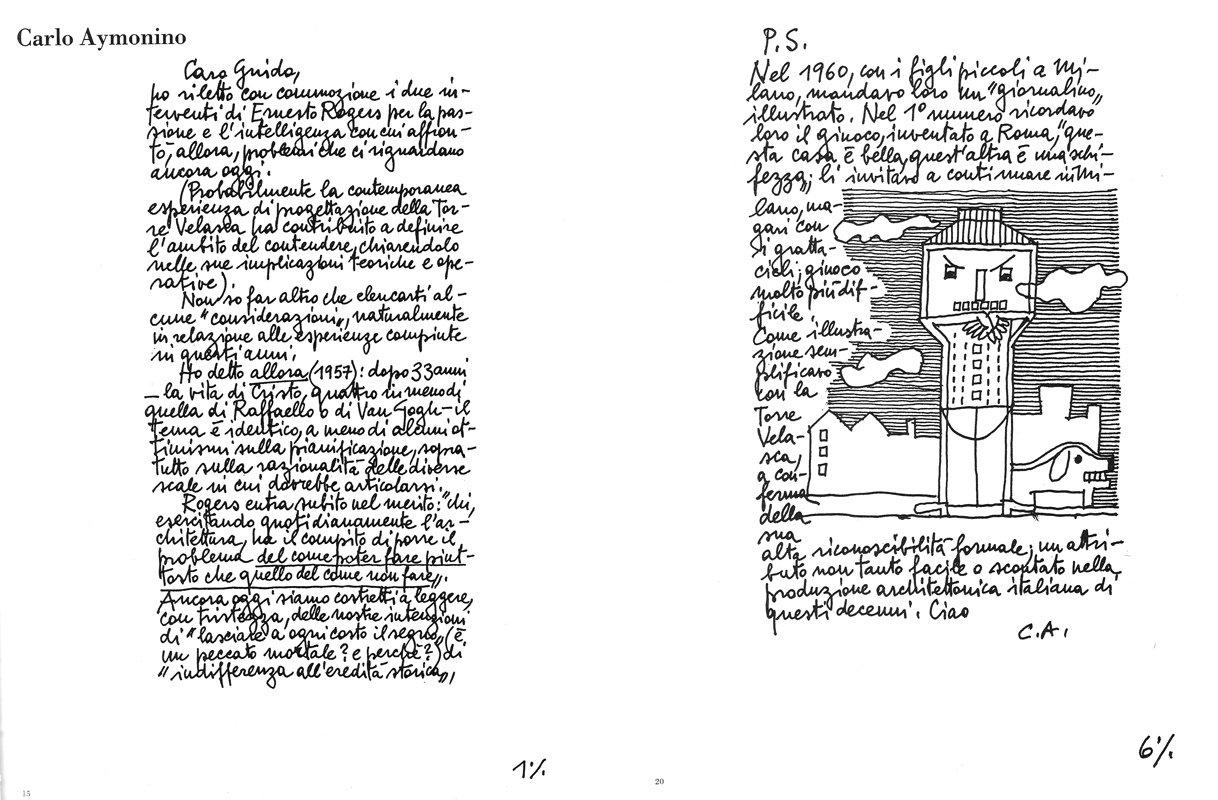

Fig. 12 - Guido

Canella, Letter of invitation to remember Ernesto N. Rogers twenty

years after his death, in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 3, April 1990,

p. 14.

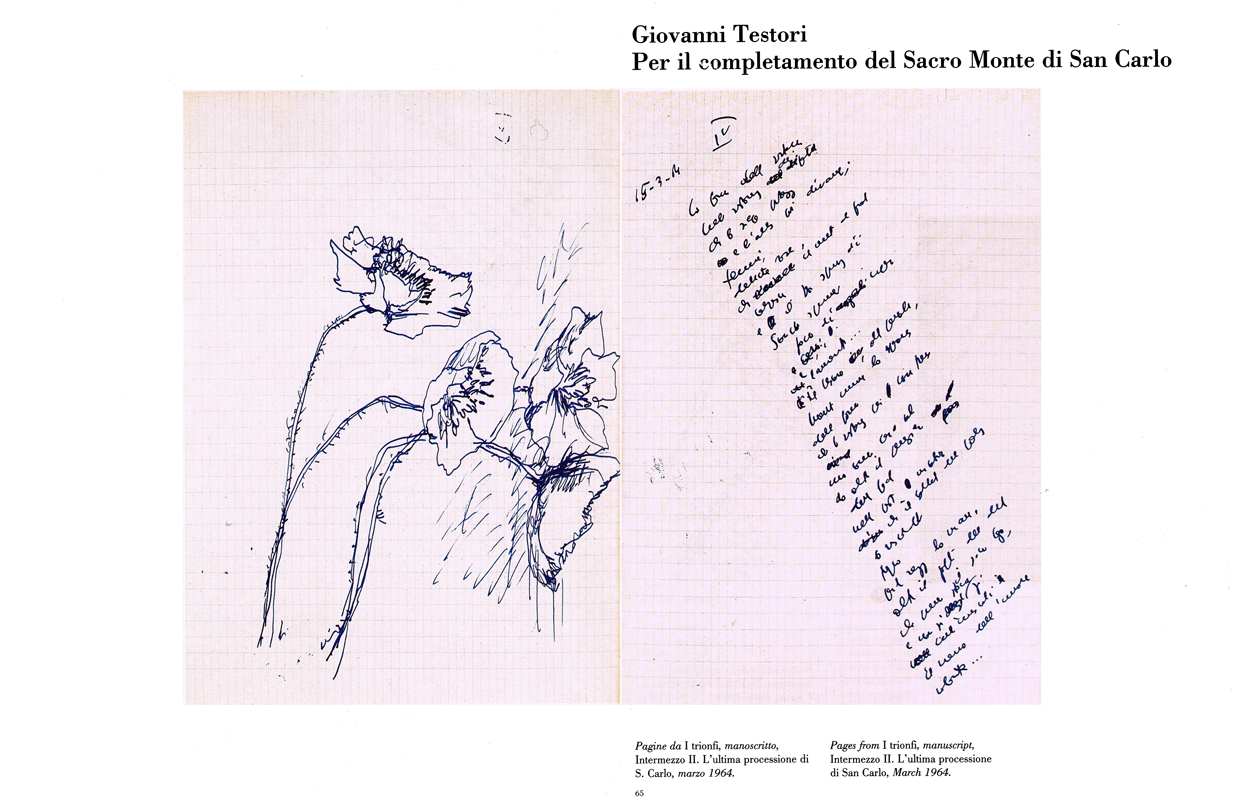

Fig. 13 - Giovanni

Testori, Initial pages of the contribution Project for the completation

of the San Carlo Sacro Monte, in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 9, June

1993, pp. 64-65. For that number, Canella had invited some architects

and friends of the newspaper to make some proposals for the completion

of the Sacro Monte di San Carlo in Arona, which remained unfinished.

Testori, then in the hospital, had contributed with a portrait of San

Carlo and some excerpts from his Triumphs. Carlo Aymonino, Ignazio

Gardella, Philip Johnson, Gianugo Polesello, Aldo Rossi and Luciano

Semerani had joined in the invitation of Canella.

Fig. 14 - Carlo

Aymonino, Testimony for Ernesto N. Rogers twenty years after his death,

in «Zodiac», n.s., n. 3, April 1990, pp. 20-21.

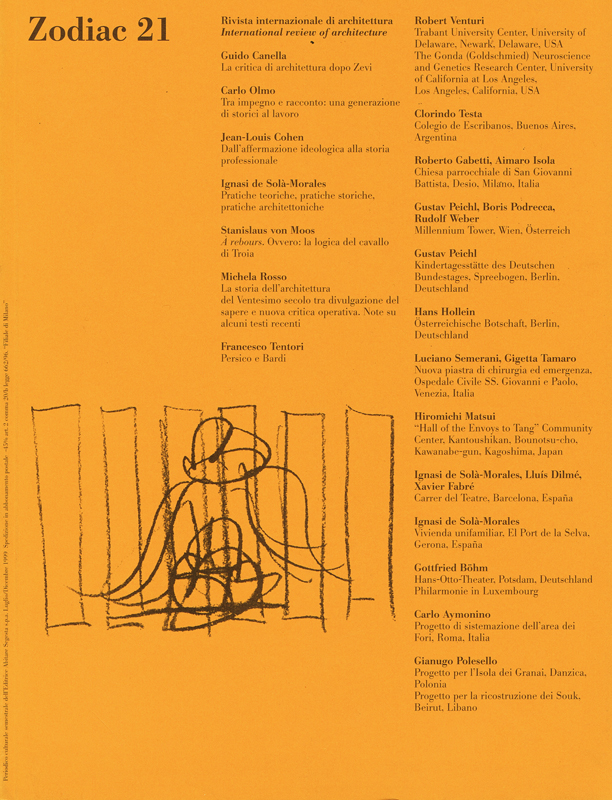

Fig. 15 - Cover

of the number 21 of «Zodiac», the latest in the new series,

December 1999, dedicated to Architectural criticsm after Zevi.

Fig. 16 - Steering

Committee for the setting of numbers 5 and 6 in the residence of the

Renato Minetto editor in Sestri Levante, 28-29 July 1990: we recognize

Carlo Aymonino, Guido Canella, Ignazio Gardella, Renato Minetto, Renzo

Zorzi.