The poetic hand of Alessandro Anselmi

Alessandro Brunelli

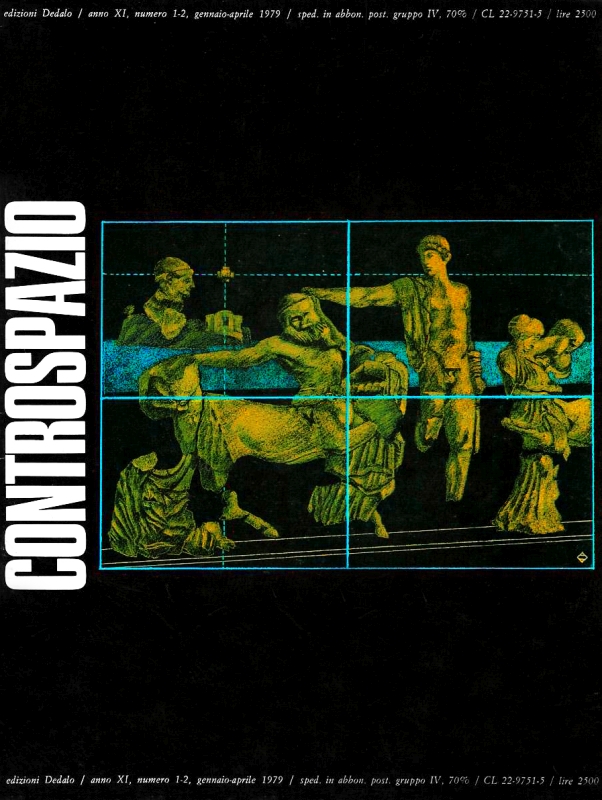

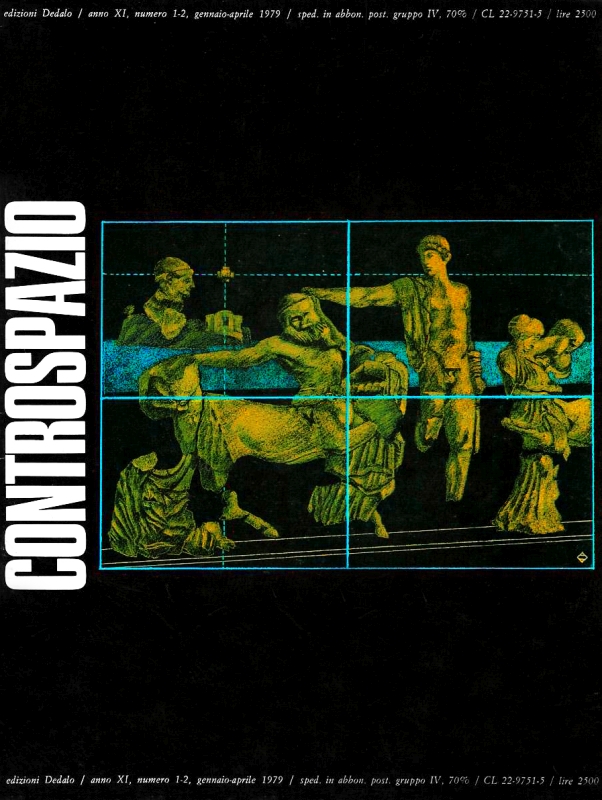

Fig.

1 - A. Anselmi, A. Anselmi, drawing for the cover of Controspazio 1-2

(gennaio-aprile 1979).

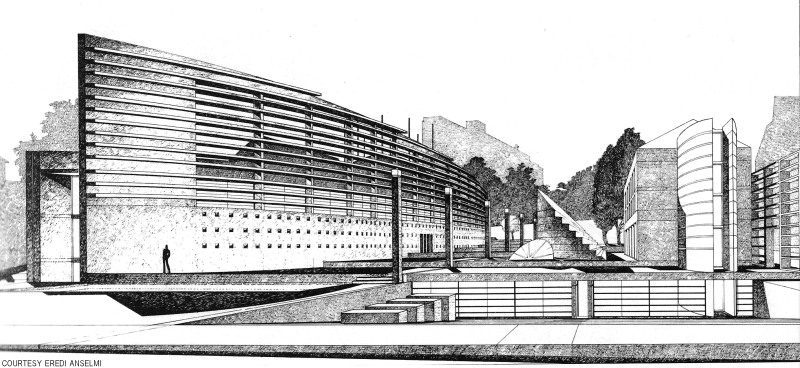

Fig.

2 - A. Anselmi, drawing of Rezé Town hall, Nantes,

1987-89(from Alessandro Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto, Milan

2004).

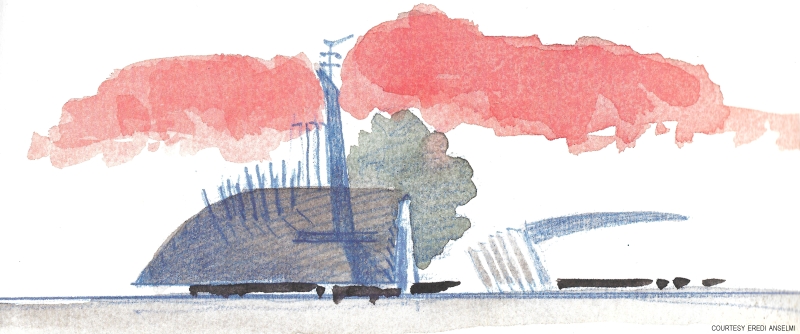

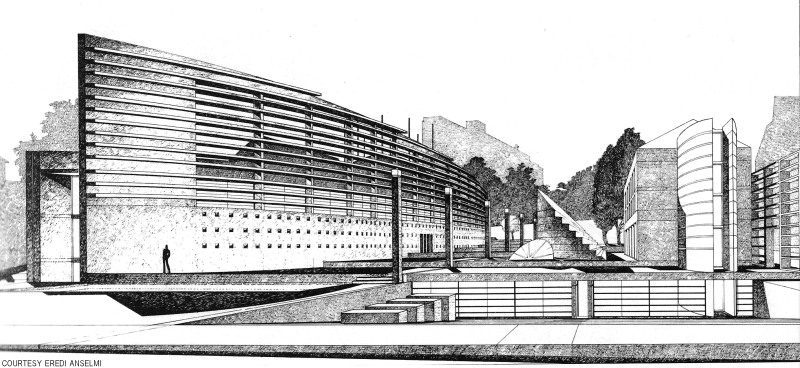

Fig.

3 - A. Anselmi, competition perspective of Rezé Town hall,

Nantes, 1987-89 (from Alessandro Anselmi: piano

superficie, progetto, Milan 2004).

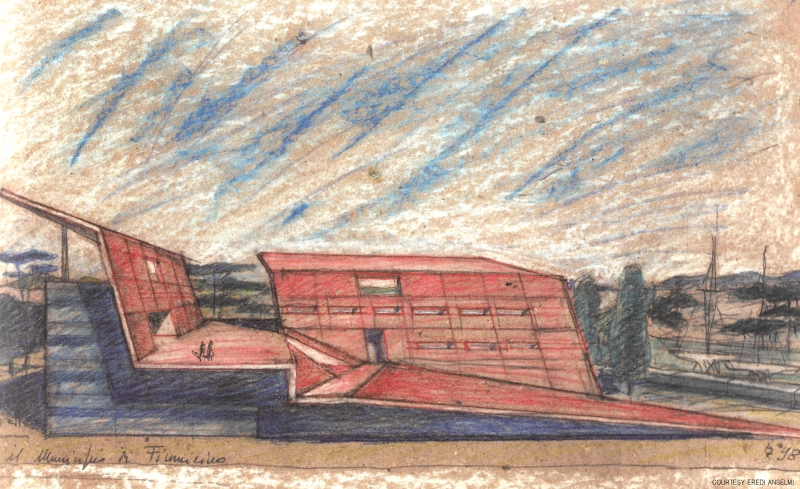

Fig.

4 - A. Anselmi, Rezé Town hall, Nantes, 1987-89, (Photo A.

Brunelli).

Fig.

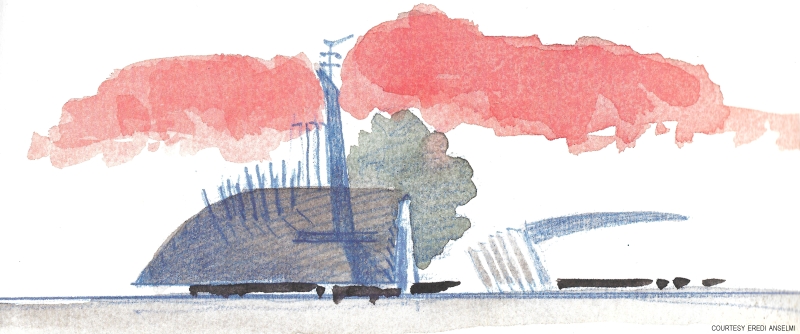

5 - A. Anselmi, drawing of Terminal and Shopping centre in Sotteville,

Rouen, 1993-95 (from Alessandro Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto,

Milan 2004).

Fig.

6 - A. Anselmi, drawing of Terminal and Shopping centre in Sotteville,

Rouen, 1993-95 (from Alessandro Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto,

Milan 2004).

Fig.

7 - A. Anselmi, Terminal and Shopping centre in Sotteville, Rouen,

1993-95, (Photo A. Brunelli).

Fig.

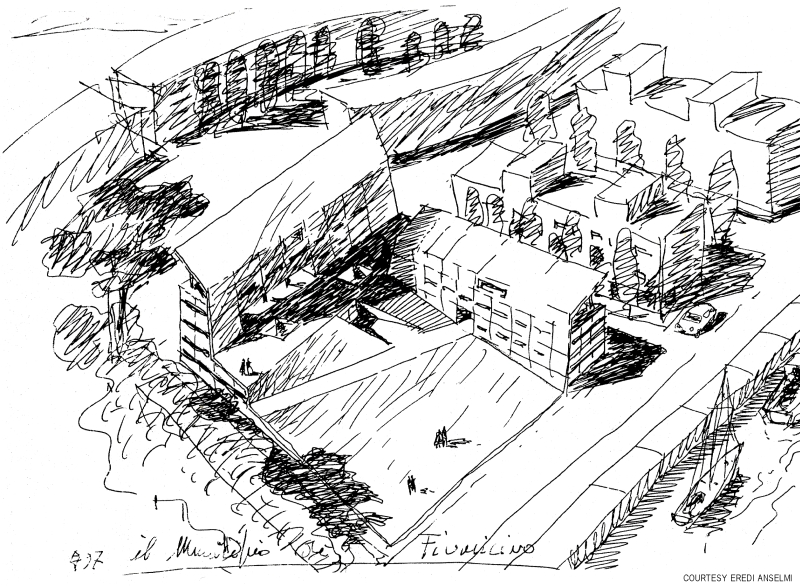

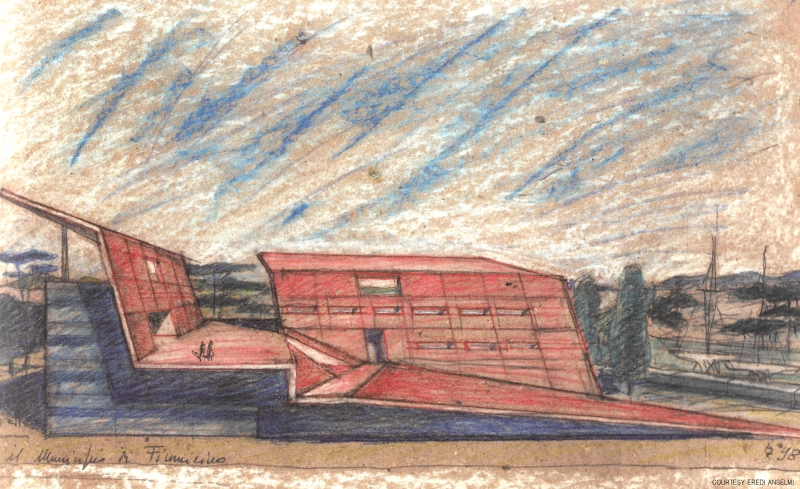

8 - A. Anselmi with M. Castelli, P. Pascalino e N. Russo,

Anselmi’s drawing of Fiumicino Town hall, Rome, 1996-2002

(from

Alessandro

Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto, Milan 2004).

Fig.

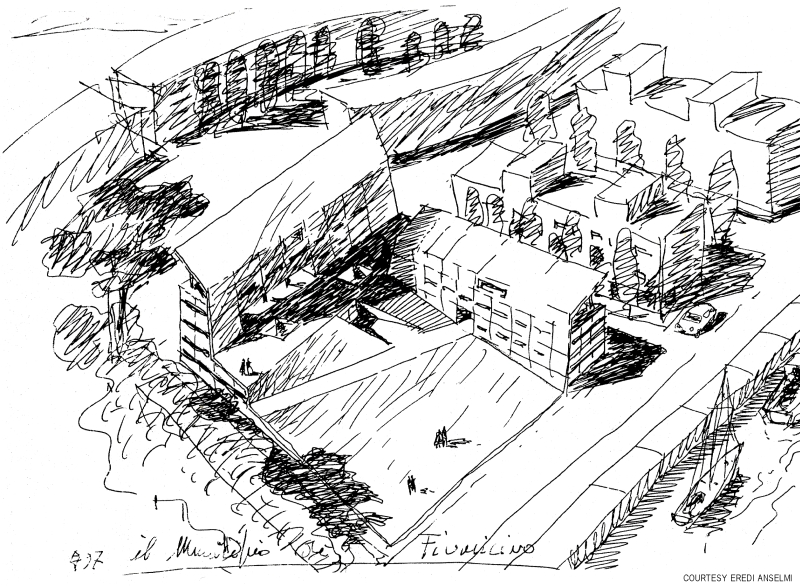

9 - A. Anselmi with M. Castelli, P. Pascalino e N. Russo,

Anselmi’s perspective of Fiumicino Town hall, Rome, 1996-2002

(Photo A. Brunelli).

Fig.

10 - A. Anselmi with M. Castelli, P. Pascalino e N. Russo, photo (A.

Brunelli) of Fiumicino Town hall, Rome, 1996-2002.

In the fourth edition of the Modern Architecture

Kenneth

Frampton inserts the town hall of Rèze-les-Nantes by

including

Alessandro Anselmi among the masters of the second half of the 20th

century (Frampton 1993, p. 390). Twelve years had passed since

Frampton’s own refusal to participate as invited curator in

the

first Architecture Biennale in 1980.

The English historian in fact renounced the Venetian

exhibition,

describing it as postmodern: «I see the Biennale as a

pluralist-cum-postmodernist manifestation. I am not all sure that I

subscribe to this position, and I think I will have to keep my distance

from it» (Frampton 1980, in Portoghesi 1980, p. 9).

Also taking a distance from the Biennale itself is Alessandro

Anselmi, who participated in the architecture exhibition as a member of

GRAU: Gruppo Romano Architetti Urbanisti. As Anselmi himself states:

«When we arrived in Venice [...]: we considered the so-called

experience of history over, so we began to review the years of the

birth of the Modern Movement» (Anselmi 2000, in

D’Anna

2000, p. 48).

The Gruppo Romano formally never disbanded while Alessandro

Anselmi,

starting in 1980, began a solitary path celebrated by his first solo

exhibitions at the Architettura Arte Moderna gallery in Rome (1980) and

at the American Institute of Architects in New York (1986). The

exhibitions reveal the talent of Anselmi’s drawing, which

describes a poetics in continuous evolution; a sign that will

increasingly move away from the fixed geometries of the GRAU to immerse

itself in an anti-classical and expressionist trajectory.

It is no coincidence that in 1982, Manfredo Tafuri described

Alessandro Anselmi’s work in progress with these words:

The recourse to history and memory [...] loses its

primitive

emphatic traits, and is «secularly» confronted with

a tight

game of closed forms and distortions [...]. Despite the common origins

and vague assonances, the distance between Anselmi’s poetics

and

Grau’s pastiches has become unbridgeable. (Tafuri 1982, p.

219)

If the Gruppo Romano continues to constitute the theoretical,

and in

part figurative, foundation of Anselmi’s poetics, drawing is

undoubtedly the true creative act at the basis of every GRAU and

post-GRAU project. Through the art of the hand, Alessandro Anselmi

refines his sensitivity in shaping the figurative qualities of spatial

forms that gradually become increasingly authoritative architectures.

Anselmi’s drawing, playing on different techniques

and the

light-shadow contrast of the Città Eterna, is an intense

stroke

that appears gestural in the invention phase, and more composed in the

representation phase. But it is precisely in the sketch, in the first

creative act, that Anselmi’s poetics is revealed: a poetics

in

which the architectures arise from a profound reading of the context

despite experimenting with heterogeneous figurations.

Alessandro Anselmi not only practices drawing as the

conception,

experimentation and representation of architectural form but, as a

professor and editor of several magazines, reflects on its value

through numerous writings.

The lesson of Anselmi’s drawing thus has a twofold

value: on

the first side the theoretical reflections that narrate the art of the

hand as the only necessary act to educate taste and conceive the formal

qualities of architecture; on the other side the practice of the

architect Anselmi that reveals the close relationship between authorial

sign, conception and poetics.

Reflections on the practice of

drawing: from the formation of taste to the

architectural idea

At the Vorlehre of the Bauhaus, students

acquired

sensitivity to formal problems by refining their gaze and by practicing

drawing and plastic modelling (Argan 1951, pp. 31-84). Alessandro

Anselmi’s education is based on the same principles: drawing

is

the necessary practice to form personal taste and to design

architecture. The Roman master reflects on the value of the art of the

hand through numerous texts that appear in didactic programs, books and

magazines[1].

In the Principi didattici e fondamenti della

composizione architettonica, Anselmi, in analogy to the Vorlehre

of the Bauhaus, attributes to drawing, in addition to sight, the

function of forming the taste of the student-architect who was to train

himself through the exercises «of visual composition [...]

realised [...] with graphic techniques» (Anselmi 1995, p.

23). In

the Principi, the aesthetic primacy of

architecture as part

of the universe of the other figurative arts is also made explicit. For

Anselmi, the exercise of drawing is a fundamental practice: it is the

cognitive act that had always marked training in the beaux-arts

school.

how will it ever be possible to imagine the construction path

of the

future architect, the birth and taking root in him of techniques for

manipulating form without [...] adequate experimentation [...]? In the

academic school, the problem was entrusted to the teaching of drawing

according to the principle that considered the graphic representation

of nature to be the basis of all figurative research, therefore also of

architecture. (Anselmi 1997c, p. 8)

In 1979, three years before his first appointment as

a

professor at the University of Reggio Calabria, Alessandro Anselmi

anticipates the same themes that appeared in the didactic texts in a

very refined article: the writer is not Anselmi professor but Anselmi

editor of Controspazio (Anselmi 1979, pp. 80-83).

In the

essay, the Roman architect uses Vasari’s words to describe

how

the activity of drawing is necessary to refine individual sensitivity

and to give life to the idea and «manner».

Drawing is thought and language, it is: «the most

penetrating

tool of architectural investigation [...] and not only as

«design», that is, as experimentation and

verification of

the architectural idea, but rather as an instrument of the idea itself,

as the first poetic technique of orientation in that dark

space»

(Anselmi 1979, p. 82). For Alessandro Anselmi, drawing is far from any

Enlightenment conception and belongs to the universe of contemporary

art: it is noumenon and phenomenon, it is

ideation-experimentation-representation, it is the irreplaceable poetic

act of the hand in the creative process of architecture.

It is precisely the question of manual practice, dear to

Anselmi’s heart, that is the conditio sine qua non

underlying the conception of spatial forms. Despite an initial openness

to the world of the digital and the recognition of the efficiency of

the electronic instrument in the definition of the project (Anselmi

2000), the Roman architect returns to reflect on the art of the hand as

an insuperable instrument of design thinking in which «the

traces, daughters of the gesture, – are – direct

witnesses

of the emotions and difficulties of figuration» (Anselmi

2004b,

p. 29).

In the age of “disposable” culture, in

which the role of

the architect approaches that of the fashion designer forced to produce

short-term images, the «inseparable unity between concept and

form in architecture» (Anselmi 2004b, p. 29) cannot be

supplanted

by digital processing. The complexity of Anselmi’s projects,

conceived before the advent of computer graphics, testifies to how

fundamental the art of drawing was in inventing articulated spaces that

were faithful to the initial idea. The town hall in

Rezé-les-Nantes (1985), the terminal in Sotteville-les-Rouen

(1993) and the building in Fiumicino (1995), three architectures that

are manifestos of Anselmi’s poetics, reveal to us how the

built

space has never betrayed the conceptual sign.

The anselmian sign poiesis

From 1980 onwards, Alessandro Anselmi’s design

activity has

produced numerous architectures marked by completely different

figurative outcomes. More than in the elevations, compositional

analogies can be read in the juxtaposition of planes and surfaces

around a void: the true trait of Anselmi’s poetics. The

churches

of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Santomenna (1981) and San Pio da

Pietrelcina in Rome (2005), placed at the extremes of his professional

career, are clear examples of this. Both sacred buildings, far from

each other in the figuration of the elevations, are characterized by

curved fragments that determine the internal spaces: in the first one,

two vertical partitions curve the plan without ever touching each

other, in the second one, the roof becomes a drape that generates a

sequence of arches in the elevation.

If we consider, at this point, Alessandro Anselmi’s

language

as a problem of secondary plasticity (Pagano 1930, p. 13), or of

writing elevations, the Roman architect’s work would seem to

escape any code. But if we instead established a correspondence between

primary plasticity (Pagano 1930, p. 13) and void, or surfaces (planes)

and space, we would realise that there is a recurring code. This code

emerges even more when we look at the conceptual drawings of the

projects: the graphic synthesis of Alessandro Anselmi’s

poetics.

The sketches also reflect the expressionist character of the

Roman

architect who, despite experimenting with heterogeneous graphic

techniques (pastels, pencils, charcoal, biro), maintains the same

gestural expressiveness in his impetuous stroke; a stroke that stops to

define an architecture capable of relocating itself (Anselmi 1994, p.

6) and giving order to the dust of contemporary conurbations. In fact,

Anselmi’s conceptual sign originates from the confrontation

with

places: the traces of “exploded contexts” [2]

guide future architectural signs in the same way as the veining of

Carrara blocks were capable of suggesting Michelangelo’s

sculptures.

The design sketch comes to life from the representation of the

context, which for Anselmi is not a cartographic drawing, but the

«aesthetic presentation»

(Anselmi 1994, p. 7) of

the place readable through the lens of the figurative arts

«in

the same way as one sees a work by Vedova or Fautrier»

(Anselmi

1994, p. 7).

The “need for the archetype” has turned

into a need for

“place analysis”. In my recent projects, the

apparent

eternity of the icon is increasingly confused with the

“trace” that con-forms a site [...]. But the

“trace” is, first, a “ground

drawing” full of

its deformations and infinite complexity; however, this

“ground

drawing” appears, once again, as a geometric abstraction

that, by

transforming the concrete concreteness of the property enclosure (the

“historical truth”) into a plane or surface, makes

the

“trace” available to assume iconic values. (Anselmi

2004a,

p. 39)

Anselmi’s architectures, never exact and

crystalline,

always appear as geometries deformed by the signs of the context

(Anselmi 1994, p. 7) and by the desire to create «landscape

ensembles» (Anselmi 1979, p. 82); whether in an external

space or

an internal one. A poetics incapable of designing single architectures

but only ensembles of fragments (planes or surfaces) or

«small

buildings assembled and embedded [...] in archaeological

enclosures» (Anselmi 1997a, p. 62).

Anselmi’s sketches, of undoubted figurative value,

become

increasingly expressionist, like his architecture, as one moves further

and further away from the GRAU experience; an experience in which

Anselmi’s talented stroke is still recognizable.

Rereading the conceptual drawings of the three architectures

mentioned, the public buildings for Rezé-les-Nantes (1985),

Sotteville-les-Rouen (1993) and Fiumicino (1995), it is possible to

identify the traits of Anselmi’s poetics. The three buildings

reveal three different figurative investigations that range from the

“neo-art-déco” of Rezé

(Frampton 1993, p.

390), to the zoomorphism[3]

of the terminal in Rouen, to the “informal”

architecture of Fiumicino.

The final image of the French town hall still appears linked

to an

abundance of “decorative” signs reminiscent of the

GRAU

period, but only in Rouen and Fiumicino the figurations become even

more abstract. Beyond the final images of the three architectures, the

line sketches tell about the same design strategy: the poetics of

fragments around a void. In Rezé, the elliptical tower and

the

“mask” (Anselmi 2004a) of brise-soleil

tend the space towards the unitè

d’habitation;

in Rouen, the roofing delimits the main space in which the volumes of

the commercial areas are placed; finally, in Fiumicino, the surface

rises from the ground, generating two distinct bodies and a public

void. Anselmi’s sketches also show «the desire

[...] for

context and the impatience to interact» (Tafuri 1982, p.

219),

which is reflected in the imagining of the architecture first

externally and then internally:

My architectures are not objects – with an

inside and an

outside – but are like a bridge, between an outside and an

inside. The void makes it possible to design the relationships between

the elements that make up this void and to reason about the physical

quality of this void. (Anselmi 2004, in Guccione 2004, p. 22)

Anselmi imagines his architecture from the outside to the

inside

through human or bird’s-eye views that recall the Roman

paintings

of the masters Poussin, Cambellotti and Sartorio (Anselmi 2000, p. 67).

From landscape views to perspective sections in which exterior and

interior interpenetrate, Anselmi investigates architecture in relation

to landscape. But the mythical referent of Anselmi’s

landscape is

undoubtedly Rome: the city par excellence of Venturi’s

stratification and contradiction, which influenced his poetics and

graphic line.

Alessandro Anselmi’s sketches are the product of a

corrupted

sign, a sign that connotes spaces through a dense contrast of light and

shadow; that chiaroscuro that enhances the

baroque moulding of the Eternal City.

But if Anselmi’s poiesis is that creative

act in which

the gesture of the hand gives life to architectural thought, from the

reading of places to the language of fragments around the void, what is

the creative energy behind this process?

For Alessandro Anselmi, an unquestionable talent of the hand,

there

is only one vital energy at the basis of every creative process:

solitude.

Solitude [...] is indispensable to the creative act, [...] the

mother of all spatial awareness and every image. Solitude is a

necessary condition for the difficult retrieval of information, for

cultural nutrition, for the dialectical work that slowly or suddenly

conforms images, makes them possible, transforms them into communicable

code, into project. (Anselmi 2003, p. 9)

Loneliness, a trait that has distinguished the Roman

architect's creative moment, is also the term that best describes

Alessandro Anselmi's career: from his solitary path with respect to the

GRAU, to his personal celebration beyond the Alps, to his isolation in

the Italian panorama that has ousted him from the creation of many

works. Perhaps the inertia of the capital, perhaps the distance from

the power ganglia, Alessandro Anselmi leaves us few architectures to

visit but many to understand on paper through the signs of his poetic

hand.

Notes

[1]

Anselmi’s activity as

a writer, and not as a theorist as he claims, is certainly less well

known than that of Anselmi the architect, but it is nevertheless of

considerable interest for the acuity of its form and content:

«This interest in theoretical speculation is true, however I

have

never had the pretension of a true organic organisation of these

reflections of mine». (Anselmi 2000, in D’Anna

2000, p. 48).

[2]

«In other words, it

is necessary to get used to [...] considering the “form of

the

place” (now distinguishable even in the

“non-form” of

the informal tendency) as a dialectical referent of the

“architectural form” ». (Anselmi 2004, in

Guccione

2004, p. 21).

[3]

«The fascination of

Calder’s static sculptures or, also, the great sculpture of

Chicago, as well as the atmospheres of some of Arp’s and

Miró’s paintings [...]; an imagery [...] of signs

with

forms of natural origin» (Anselmi 1997b, p. 165).

References

ANSELMI A. (1979) – “Appunti sul disegno

di architettura

e sulla metodologia della progettazione architettonica per

«insiemi»”. Controspazio 5-6

(July-August).

ANSELMI A. (1994) – “La forma del

luogo”, in DEL MARO C., L’architettura

della stratificazione urbana. Edizioni Artefatto, Roma.

ANSELMI A. (1995) – “Principi didattici e

fondamenti

della composizione architettonica”. In: ALTARELLI L., FONDI

D.,

MARRUCCI G. (edited by), La didattica del progetto. Quaderni

di progettazione architettonica. Clear Edizioni, Roma.

ANSELMI A. (1997a) – “Cinque progetti per

Santa

Severina, paese della Calabria Ionica, 1974-80”. In: CONFORTI

C.,

LUCAN J. (edited by), Alessandro Anselmi architetto.

Electa, Milano.

ANSELMI A. (1997b) – “Alcune riflessioni

sul progetto

urbano per Sotteville-lès-Rouen, Jurassik Park”.

In:

CONFORTI C., LUCAN J., (edited by), Alessandro Anselmi

architetto. Electa, Milano.

ANSELMI A. (1997c) –

“L’insegnamento ai

primi anni della scuola di architettura. Una didattica per la

formazione del gusto”. In: ALTARELLI L. et. al., Forme

della composizione. Kappa, Roma.

ANSELMI A. (2000) – “L’arte

necessaria: il

disegno. Alcune riflessioni sui progetti di Franco

Pierluisi”.

Disegnare idee immagini, 20-21, (June-December).

ANSELMI A. (2003) – “Il nuovo municipio di

Fiumicino: una storia”. Casabella 709, (March).

ANSELMI A. (2004a) – “La maschera e il

suolo”. In: GUCCIONE M., PALMIERI V., (edited by), Alessandro

Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto. Federico Motta Editore,

Milano.

ANSELMI A. (2004b) – “Il disegno: una

pratica desueta?”. In: GUCCIONE M., PALMIERI V., (edited by),

Alessandro Anselmi: piano superficie, progetto.

Federico Motta Editore, Milano.

ARGAN G. C. (1951) – “La pedagogia formale

della Bauhaus”. In: Walter Gropius e la Bauhaus.

Einaudi, Torino.

BARILLI R. (2005) – L’arte

contemporanea. Da Cézanne alle ultime tendenze.

Feltrinelli, Milano.

D’ANNA D., (a cura di) (2000) – Saper

credere in architettura: quarantaquattro domande a Alessandro Anselmi.

Clean, Napoli.

FRAMPTON K. (2008) – Storia

dell’architettura moderna. Zanichelli, Bologna.

GUCCIONE M. (2004) – “Conversazione con

Alessandro

Anselmi. Roma, 14 febbraio 2004, studio Anselmi” In: GUCCIONE

M.,

PALMIERI V., (edited by), Alessandro Anselmi: piano

superficie, progetto. Federico Motta Editore, Milano.

PAGANO G. (1930) – “I benefici

dell’architettura

moderna. (A proposito di una nuova costruzione a Como)”. La

Casa

Bella 27 (March).

PORTOGHESI P. (1980) – “La fine del

proibizionismo”. In: AA. VV., La presenza del

passato: Prima mostra internazionale di architettura

[Catalogo della prima Biennale di Architettura di Venezia] La Biennale

di Venezia-Electa, Milano.

TAFURI M. (1982) – Storia

dell'architettura italiana. 1944-1985. Einaudi, Torino.