From the “soft media” to the concept

legacy of Le Corbusier and his collaborators based on Jerzy

Sołtan’s designs and teaching

Szymon Mateusz

Ruszczewski

Fig.

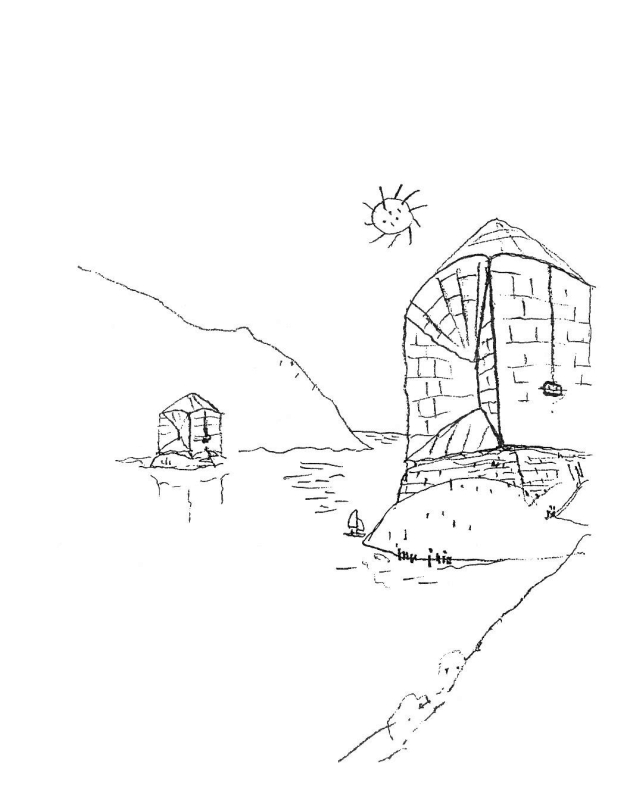

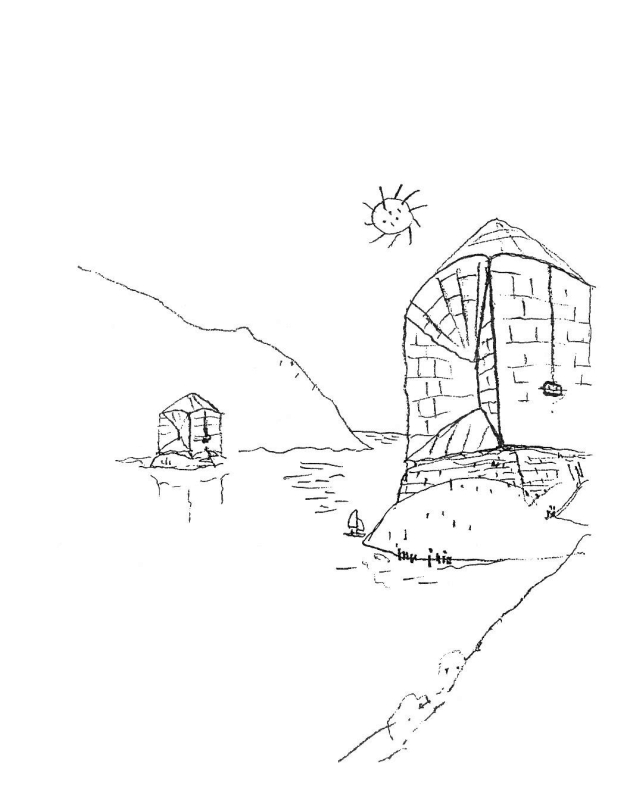

1 - Jerzy Sołtan, pencil sketch of a monument for

‘Diomede’ competition for the end of the Cold War

(1989).

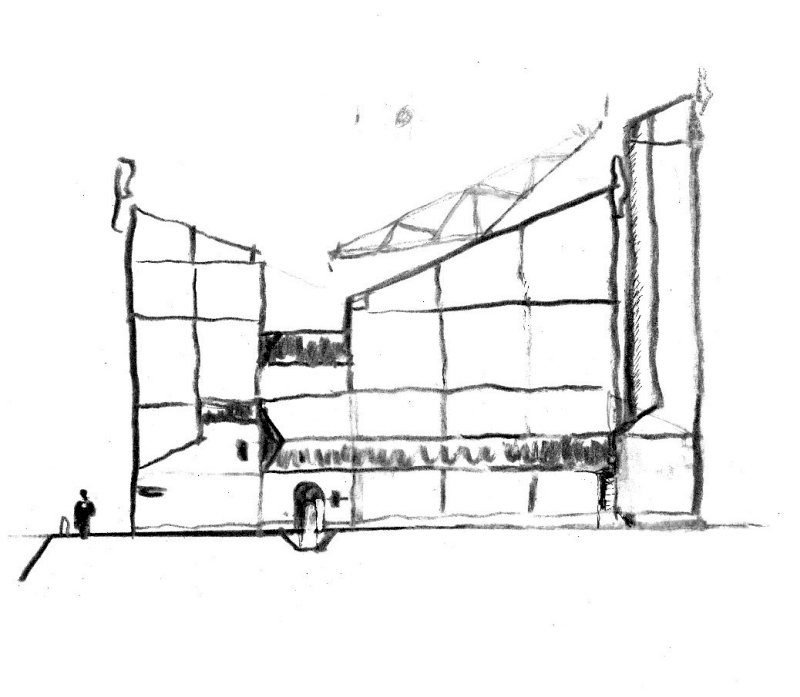

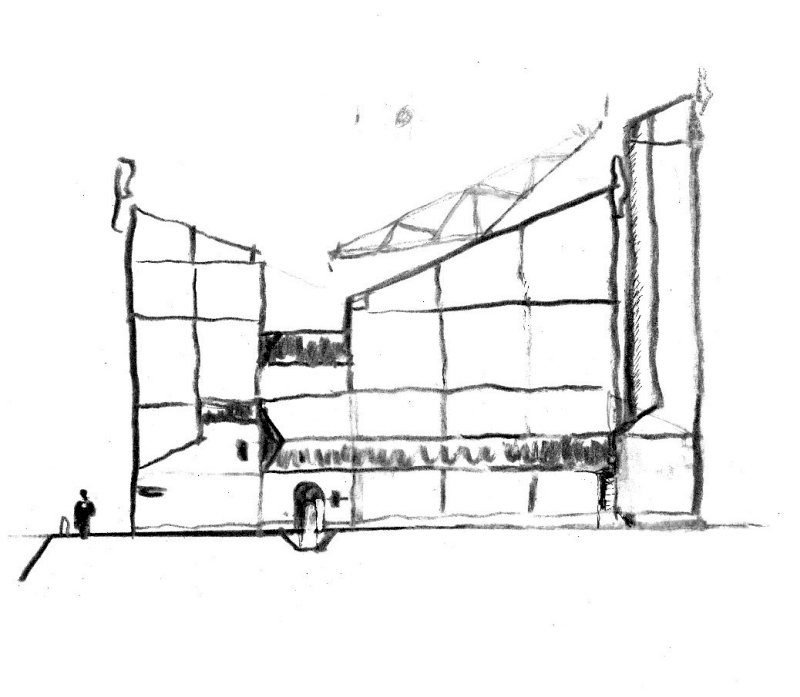

Fig.

2 - Jerzy Sołtan, pencil sketch of a church (1990s).

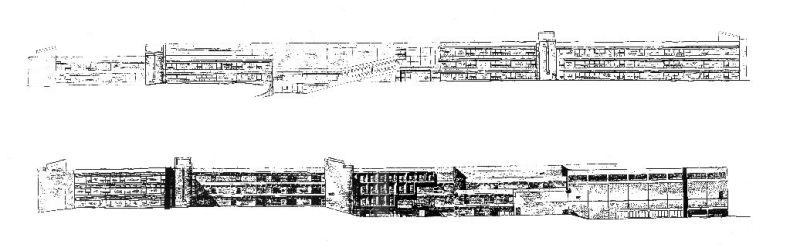

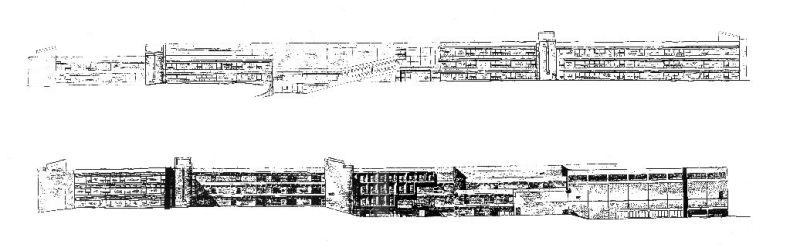

Fig.

3 - Jerzy Sołtan, charcoal-made elevations of the Salem High School

(1970-1976).

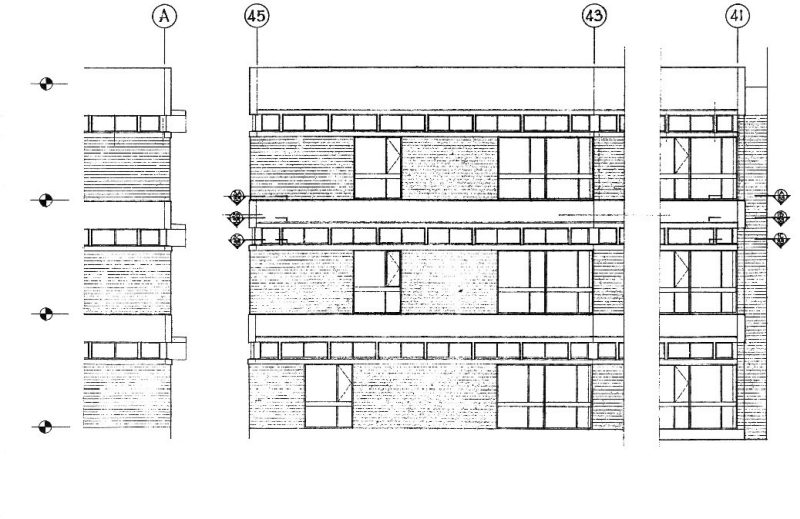

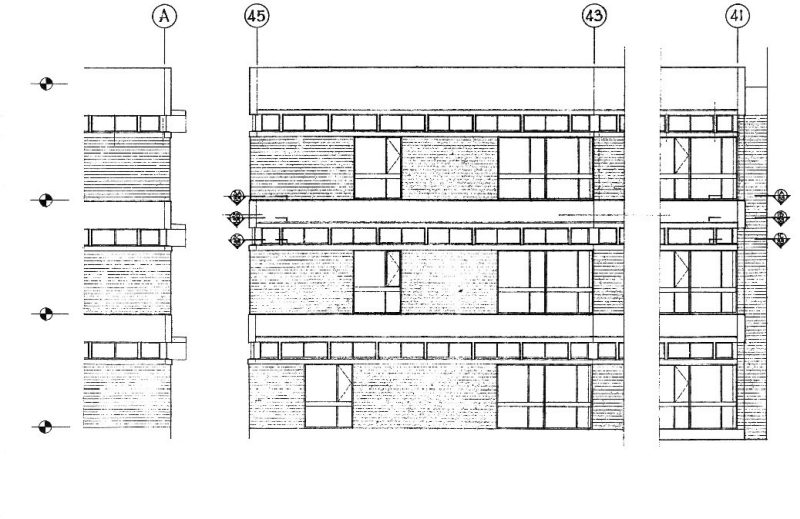

Fig.

4 - Jerzy Sołtan, technical elevation drawing of the Salem High School

(1970-1976).

Fig.

5 - Thomas Holtz, clay model of a ‘space of spiritual

retreat’ design for Jerzy Sołtan’s studio (1976).

«The initial creation moment of the project lies in

our soul and in our mind as a fluid thought, an element that cannot be

boxed at the beginning with sharper and rigid lines»

– these are words on Jerzy Sołtan’s approach

expressed by his design studio student from Harvard Graduate School of

Design (Guarracino 2020). Within the larger context of the importance

of hand drawn sketches for early design stage, this idea underlines the

relevance of “soft media” – such as

charcoal, soft crayons, and clay. Their relevance can be illustrated by

Sołtan’s teaching and by his own work, which had been

influenced by his employer in 1945-1949 and lifelong mentor, Le

Corbusier. Jerzy Sołtan (1913-2005) was a Polish modernist architect

who in addition to his own design work in Poland and in the United

States, was committed to teaching architecture at the Fine Arts Academy

in Warsaw and later at Harvard Graduate School of Design. His example

shows how Le Corbusier’s modus operandi

influenced his collaborators and how it could be passed onwards to new

generations of architects.

The article is based on extensive archival research of

designs, drawings, texts, and teaching-related documents illustrating

Sołtan’s body of work, in addition to a series of oral

history interviews with his students and colleagues from Poland and the

United States, contributing to understanding of the role of a specific

drawing technique in the creation of an architectural idea. After

explaining Le Corbusier’s approach to drawing during the

design process, the article concentrates on the role of these initial

visual explorations in Sołtan’s own architectural work and

practice. Further analysis on the application of these ideas in

Sołtan’s teaching at Harvard and of the impact it had on the

architecture students he taught enables to discuss the legacy of the

“soft media” approach.

Art, sketches, and Le Corbusier

Thanks to Sołtan, the account of Le Corbusier’s work

and routine has been very clear, as he explains in the essay

‘Working with Le Corbusier’ (1987), written first

in the 1980s and since published several times. He gives testimony of

how Le Corbusier was communicating, and of how design work proceeded.

He draws the image of Le Corbusier for whom architecture and painting

were tightly connected, but also an image of Le Corbusier who wanted to

use specific tools when working at the early stages on his designs. In

Sołtan’s account, the mornings were usually marked by Le

Corbusier’s absence who was working alone on art in his own

apartment. These paintings, artwork, and rough architectural sketches,

called by Sołtan «fine arts callisthenics», were

vital aspects to the development of Le Corbusier’s designs

(1995, p. 10). According to Sołtan, «it was for him a period

of concentration during which his imagination, catalysed by the

activity of painting, could probe most deeply into his subconscious. It

was probably then Le Corbusier produced his remarkably sensitive poetic

metaphors and associations» (1995, p. 11). In this sense,

Sołtan sees sketches and visual exploration as a vital element, not

only in Le Corbusier’s designs and projects, but also in his

theories and ideas. The importance of sketching and painting lies

exactly in the possibility of exploring what yet needs to be determined

and discovered. It means to work with rough ideas, which only later

would become clearer. It becomes evident in the account of Le

Corbusier’s sketching next to Sołtan, when the former was to

comment on mechanical pencils and more technical drawing tools saying,

«il ne faut pas immortaliser des aneries»

– one should not immortalise the

“assinine” (1995, pp. 21-22).

The “assinine” refers to the attempts,

trials, and uncertainties of the early stages of a design, when the

drawings should leave enough space for interpretation and should not

limit the further possibilities of development. To

«immortalise the assinine» would mean to yearn too

early for a definite line that prevents to alter the design. Indeed, Le

Corbusier’s sketches are called by Sołtan as «more

his digging into the subconscious, his guessing, than a finished

proposal» (1995, p. 18). It is also important to underline

that Le Corbusier wanted to apply these methods in the atelier too

– which could be easily understood from the imperative tone

he used when talking about drawing tools. Differently from many

functionalist designers, inclined to use more technical tools, Le

Corbusier wanted to follow his “pictorial thinking”

in the atelier (1995, p. 20). Therefore, Sołtan and other collaborators

were not only expected to decipher his drawings, but also to continue

to work in a similar spirit. As a result, Sołtan’s own design

workshop and artistic research stand as a manifestation of how this

approach could be shared by others.

From Le Corbusier to Sołtan’s workshop

Starting from the period of imprisonment in a POW camp in

Murnau during the Second World War, Sołtan had always had close

contacts with artists. In the camp, thanks to the high number of

intellectuals and artists amongst the prisoners, he became close with a

number of Polish painters, with whom he collaborated later in the 1950s

(Bulanda 1996). During this very same period, he started to paint much

more, probably using art as a cure for the harsh reality of

imprisonment (Sołtan 2019). That said, the importance of art and visual

research for Le Corbusier was aligned with Sołtan’s prior

experiences and interests, which resulted not only in a close

professional, but also intellectual relationship between mentor and

mentee. Both contacts with artists and Sołtan’s own painting

did develop during his stay in Paris: he was taking painting lessons

under Fernand Léger, and he entered the circle of artists

who were meeting at Le Corbusier’s apartment (Sołtan 1995, p.

51). Sołtan’s own writings from the 1950s indicate that he

was still researching new methods and forms in art, studying paintings

of various artists. In addition, a vast archive of his own artworks at

the Museum of the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw testifies of a constant

research in visual arts, in parallel to his professional work as an

architect.

In addition, he was also often producing charcoal-made

sketches, similar to Le Corbusier’s. A number of those relate

to theoretical studies of churches (fig. 2), which he was working on

continuously throughout the years until the 1990s. Similar

charcoal-made drawings were produced for other designs, especially at

the conceptual stage for a number of designs in Poland and the United

States, such as ‘Warszawianka’ sporting centre in

Warsaw or Salem High School in Massachusetts. For example, in the

drawings from Salem, he used charcoal in order to visualise shadows,

materials, and to accentuate some aspects of the design (for example,

brickwork) without establishing precise patterns (fig. 3). As Sołtan

explained in his account from Le Corbusier’s studio, the lack

of precision of these drawings were enabling him to work on the project

gradually, being able to interpret some graphical signs left by

charcoal on paper in more ways than in case of thin and precise

pencil-made lines. In relation to this approach, one of

Sołtan’s collaborators in America, Edward Lyons, manager at

the office where Sołtan was the main designer, recalls, «he

would always do sketches on tissue with charcoal; he would not pick up

a pencil or a marker. He always wanted yellow too. You could not give

him a piece of white paper» (2019). These words relate

directly to the sketching practice that Sołtan inherited from Le

Corbusier – both charcoal and yellowish tissue or

butcher’s paper were often used in the atelier in Paris.

However, Sołtan’s approach was not limiting the use of

drawing utensils to those preferred by Le Corbusier during the whole

design process, but it was specific to the initial conceptual design,

as later stages of development of these same projects normally did

involve using more technical drawings (fig. 4).

Teaching Le Corbusier and “soft

media”

The influence of Le Corbusier was not although limited to

Sołtan’s own design workshop: he did refer to the same

approach and to the importance of visual research when he was teaching,

and many amongst his students from Harvard still remember it from the

design studios. Some claim that their interest in art and artistic work

were nourished by Sołtan’s influence at the school (Holtz

2019). Indeed, he was much interested in his students’

artistic production – as is shown in his letter to his former

student at Harvard, Michael Graves, where he states, «I

personally want to compliment you particularly warmly in relation to

your paintings» (1974). His contact and correspondence with

former student and artist Jacek Damięcki on his work equally point to

the importance of visual research for the development of an

architect’s mind according to him (2019). These contacts

suggest therefore the existence of a thread of continuity of artistic

method, coming from Le Corbusier, channelled through Sołtan and his

teaching, and then passed on to the latter’s students.

In general, these exchanges illustrate how much

Sołtan’s vision of architecture was drawings-driven and it

implies how much the design process relied on drawing, painting, and

graphical exploration. In his design studios at Harvard, specific

drawings would become key features to students’ projects.

While some students remember working with plans, for others the focus

was put on sections: the choice of drawings could have been then

tailored to the specific needs of a given design or a given student

(Davis 2021, Lombard 2020, Wattenberg 2020). However, regardless of the

focus on a specific type of drawings, artistic expression was more

important. Visual research was in fact helpful in defining the parti

(a small drawing, which in the 1970s was a common reference in the

design process at Harvard) and in defining the main concept idea coming

from different layers of single problems. In addition, in theoretical

modules at Harvard, Sołtan was both illustrating to the students Le

Corbusier’s daily routine and underlining the importance of

painting for Corbusian architecture, reinforcing thus his suggestions

for more artistically skilled students. «I want them really

to know, to be able (if they wish) to apply [Le Corbusier’s

design method]», he mentioned in a note from his theoretical

seminar.

Along with illustrating the importance of the visual research

in the design process, Sołtan tried to propose the students to use

similar drawing techniques while designing. The suggestion to use

“soft media” – soft pencils, charcoal,

clay – completed Sołtan’s contribution to extending

Le Corbusier’s influence on his students. They were aimed to

facilitate exploration of ideas and leaving the possibility for the

imagination to complete a more generic drawing. The words

«don’t be so painfully precise», as he

told one of his students, illustrate well this approach (Holtz 2019).

According to Sołtan, only afterwards, after having worked with those

more malleable techniques, more practical questions related to

functionality, technology, and construction appeared, and more detailed

drawings were of use. His former student and architect Karl Fender

recalls his words from the first studio day (2020):

I want you all […] to buy clay, I want you to buy

charcoal, and I want you to buy butcher’s paper

[…]. We are going to explore ideas through these mediums,

because you are going to get filthy hands, and you are going to have

filthy drawings and rough lumps of clay to explore your thinking

– and this will focus you on the essence.....you will be

confronting the essence of the search for a truthful architecture. With

these tools, you will not fall in love with your handicraft. You will

have models that honestly and basically test your options and your

explorations.

Through getting hands dirty, through drawing these undefined

lines, there was more space left for exploring the essentials, the

basics of architecture. In some assignments, he suggested the students

to submit freehand drawings, and some students recall that their

tendency to draw in a less precise manner, using charcoal or very soft

crayons (fig. 5), was due to Sołtan’s influence (Holtz 2019).

As in his accounts from Paris, imprecise drawing during the first phase

of design was a tool to find the ideas and to understand the poetics

underlying the design. It was to detach the students from drawing

beautifully something that was not enough cross-examined, making a

direct connection between the design work, the concept (the parti),

and critical thinking and questioning – referred by some as a

constant element of Sołtan’s reviews and discussions (Wesley

2006). Another student and architect Christopher Benninger explains

this adding (2021), «his technique was to ask the student a

question that needed analysis to answer, and often it would be that

there was no possible answer. That silence was the

conclusion». Along with the drawings, constant questioning

was then another tool, which helped the students to work at the core of

their design decisions and push their ideas further.

Legacy: between Sołtan and Le Corbusier

Sołtan’s teaching was widely recognised by his

students. «I have won the lottery», commented David

Parsons referring to him having Sołtan as thesis advisor (2016, p. 54).

Amongst direct testimonies from his students, a number of them refer to

passion, help, and intensity in teaching, and only a couple remember

him as less sympathetic. In 2002, twenty-three years after his

retirement from the professorship at Harvard, Sołtan was awarded with

the Topaz Medallion, the highest recognition the American Institute of

Architects and the Association Collegiate of Architecture Schools can

give to an architecture educator. Although the award came years after

he was teaching at Harvard, the backing was impressive, including

support letters from Charles Gwathmey and Michael Graves, from Kenneth

Frampton, and from architecture professors and deans from Harvard, MIT,

and Berkeley. They all pointed to his contribution to architectural

education by teaching modernism: «Jerzy Sołtan has brought to

Harvard, and to other schools and forums, a sense that Le Corbusier,

his own mentor and friend, has been alive for an extra

generation» (Chermayeff 1989). It would have not been

possible to keep Le Corbusier alive without the importance of visual

art, without charcoal, and without getting hands dirty. As to whether

his approach is still of value, one can refer again to

Sołtan’s former students, who admit to use their experience

of being taught by him when teaching and designing themselves, even

nowadays.

References

BENNINGER C. (2021) – Interview by Szymon

Ruszczewski from 29/11/2020 and 20/01/2021, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022)

– Finding Sołtan: legacies and heritages of

modernist architecture. PhD thesis, School of Architecture,

University of Sheffield.

CHERMAYEFF P. (1989) – Letter to AIA Awards

Department from

04/01/1989. Jerzy Sołtan Nomination, AIA Archives, Washington DC.

DAMIĘCKI J. (2019) – Interview by Szymon Ruszczewski

from 28/09/2019, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

DAVIS M. K. (2021) – Interview by Szymon Ruszczewski

from

15/01/2021, 02/02/2021 and 13/04/2021, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022)

– Finding Sołtan: legacies and heritages of

modernist architecture. PhD thesis, School of Architecture,

University of Sheffield.

FENDER K. (2020) – Interview by Szymon Ruszczewski

from 19/10/2020, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

GUARRACINO U. (2020) – Interview by Szymon

Ruszczewski from 11/05/2020, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

HOLTZ T. (2019) – Interview by Szymon Ruszczewski

from 11/04/2019, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

LYONS E. (2019) – Interview by Szymon Ruszczewski

from 02/04/2019, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

PARSONS D. (2016) – Architecture

Education at Harvard Then (1965) and Now (2015). Create

Space.

SOŁTAN Jerzy (1951) – Diary notes from 11/11/1951.

Jerzy Sołtan Collection, Museum of the Fine Arts Academy, Warsaw.

SOŁTAN Jerzy (1974) – Letter to Michael Graves from

06/12/1974. Jerzy Sołtan Collection, Museum of the Fine Arts Academy,

Warsaw.

SOŁTAN Jerzy (1987) – “Working with Le

Corbusier”. In: H. Allen Brooks (ed. by), Le

Corbusier: the Garland essays. Garland, New York.

SOŁTAN Jerzy (1995) – Draft of a book On

Architecture and Le Corbusier from November 1995. Jerzy

Sołtan Collection, Museum of the Fine Arts Academy, Warsaw.

SOŁTAN Joanna (2019) – Interview by Szymon

Ruszczewski from 28/03/2019.

WATTENBERG A. (2020) – Interview by Szymon

Ruszczewski from 24/04/2020, see: RUSZCZEWSKI S. (2022) – Finding

Sołtan: legacies and heritages of modernist architecture.

PhD thesis, School of Architecture, University of Sheffield.

WESLEY R. (2006) – Lecture “All Men Are

Born Fools: a

Tribute to Jerzy Sołtan, 1913-2005” from 03/03/2006. Richard

Wesley private archive.