Figuration before form, diagrams and form drawing in the work

of Louis I. Kahn

Michele Valentino

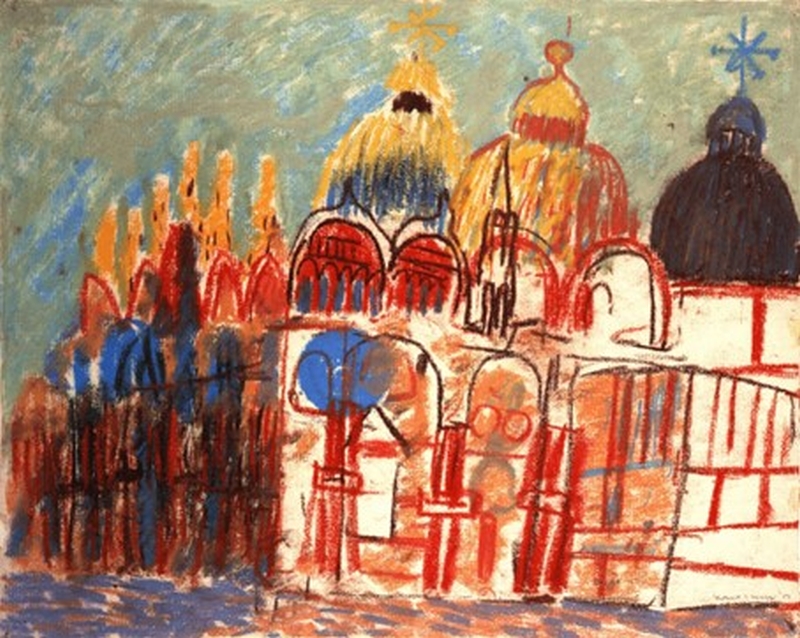

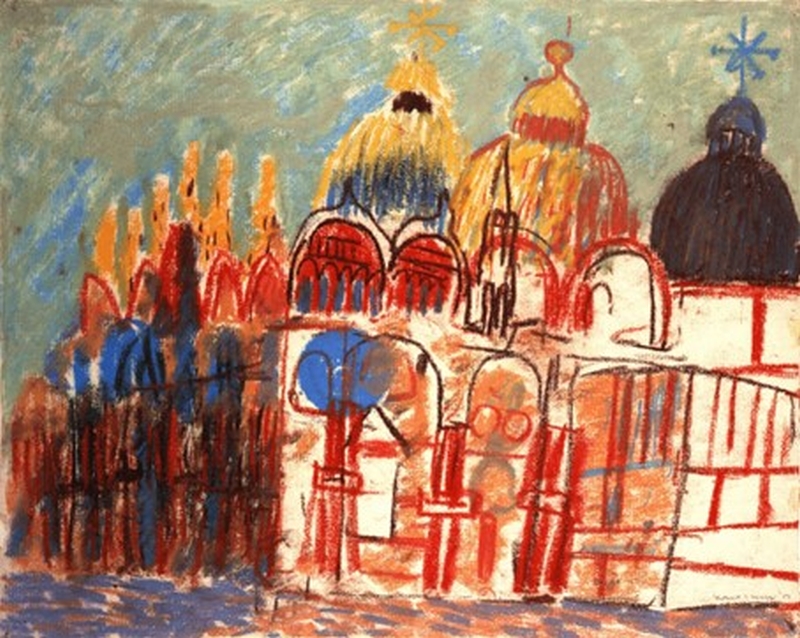

Fig.

1 - Louis I. Kahn, St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, 1951, pastel

on paper, 31.7 x 39.4 cm. Sue Ann Kahn / Art Resource, NY. (Mansilla,

2001, p. 30).

Fig.

2 - Louis I. Kahn, Parthenon’s Interior, Athens, 1951, pastel

on paper, 28.6 x 35.6 cm. Architectural Archives of the University of

Pennsylvania - Stuart Weitzman School of Design. (Mansilla, 2001, p.

83).

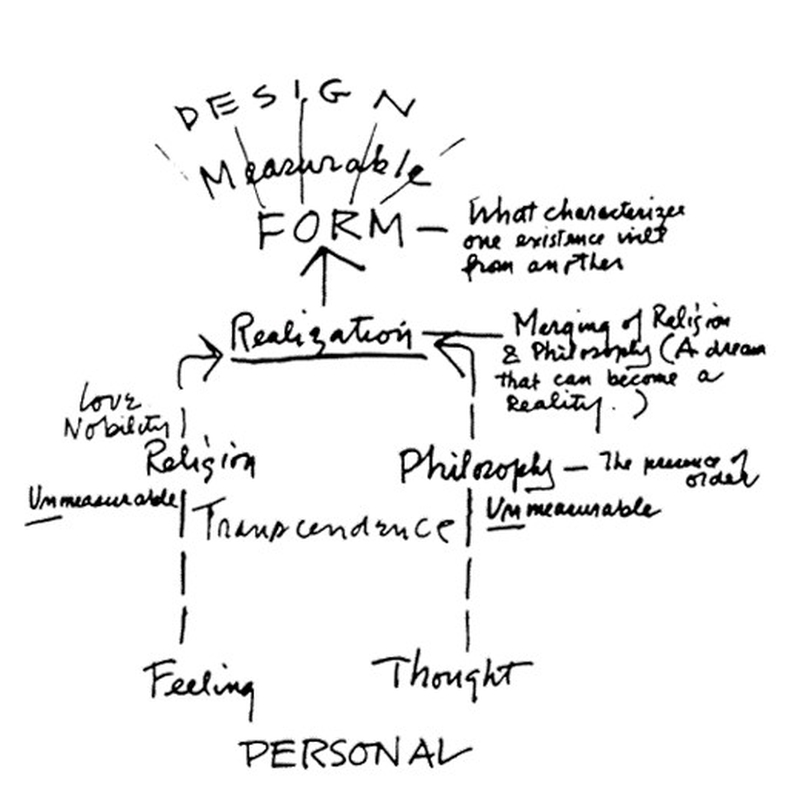

Fig.

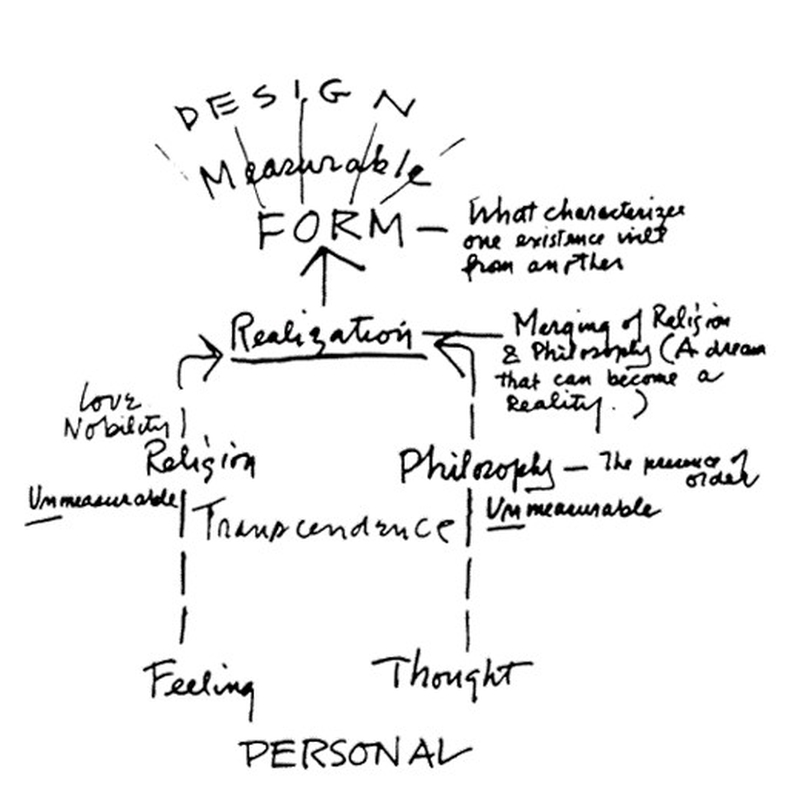

3 - Louis I. Kahn, On the creation of Form, 1960. (Tyng, 1984, p. 30).

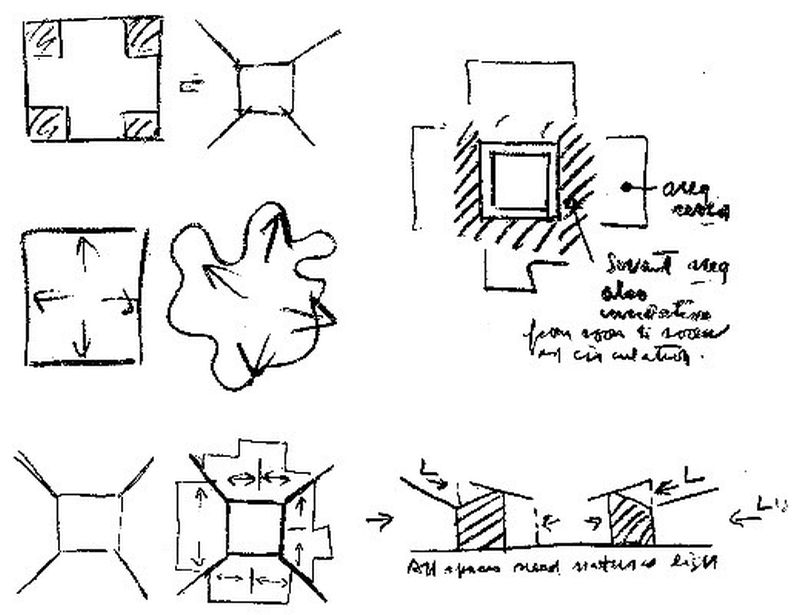

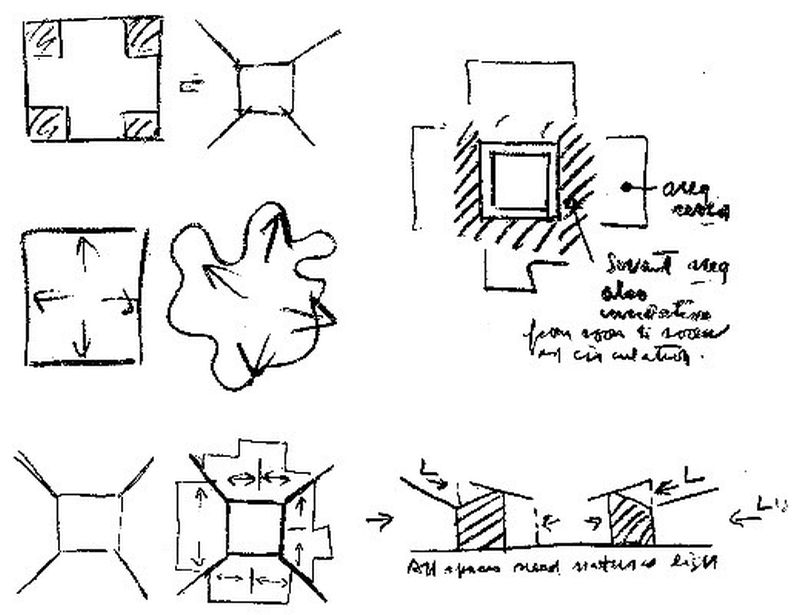

Fig.

4 - Louis I. Kahn, Form drawing of the Goldberg House, 1959, Pencil on

paper. Louis I. Kahn, University of Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission. (Kahn, 1961, p. 13).

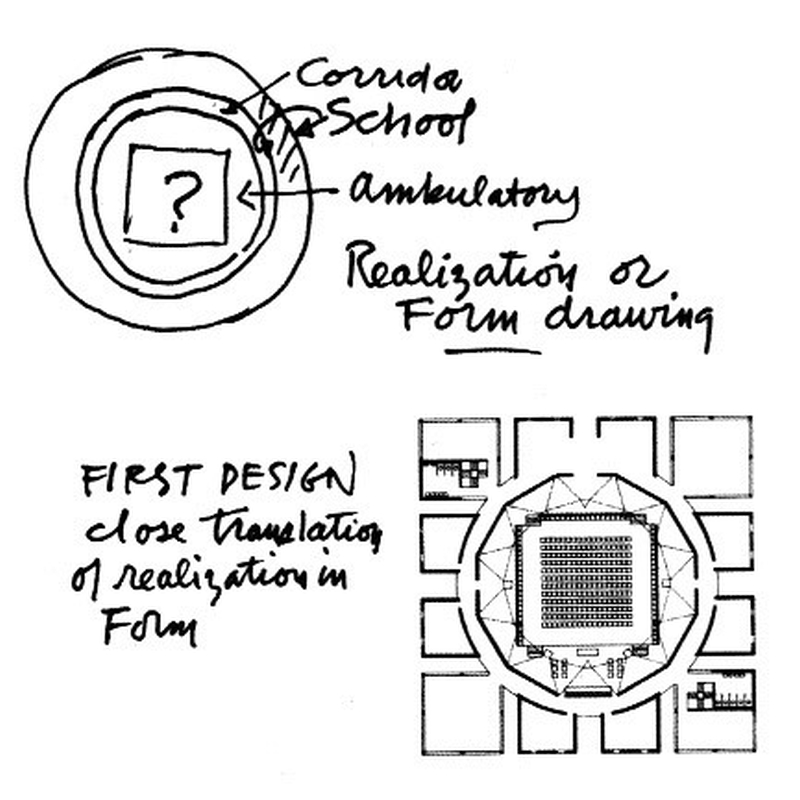

Fig.

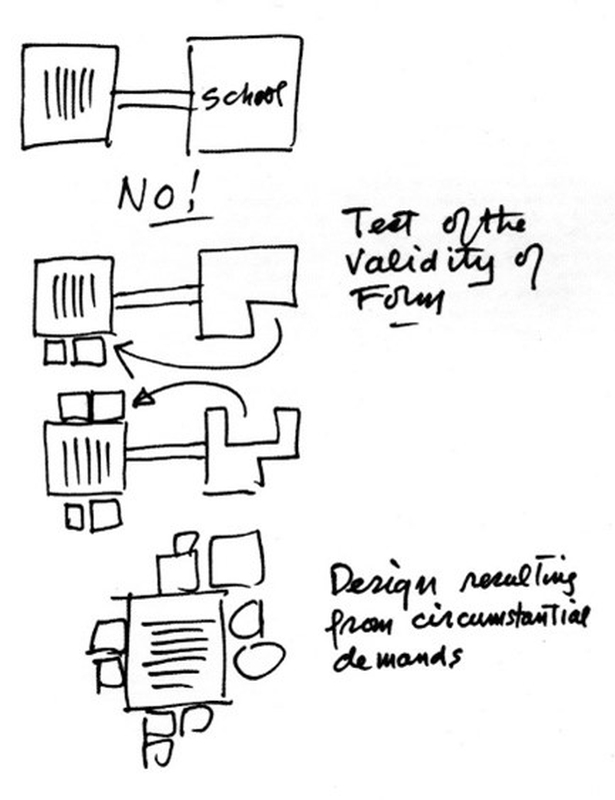

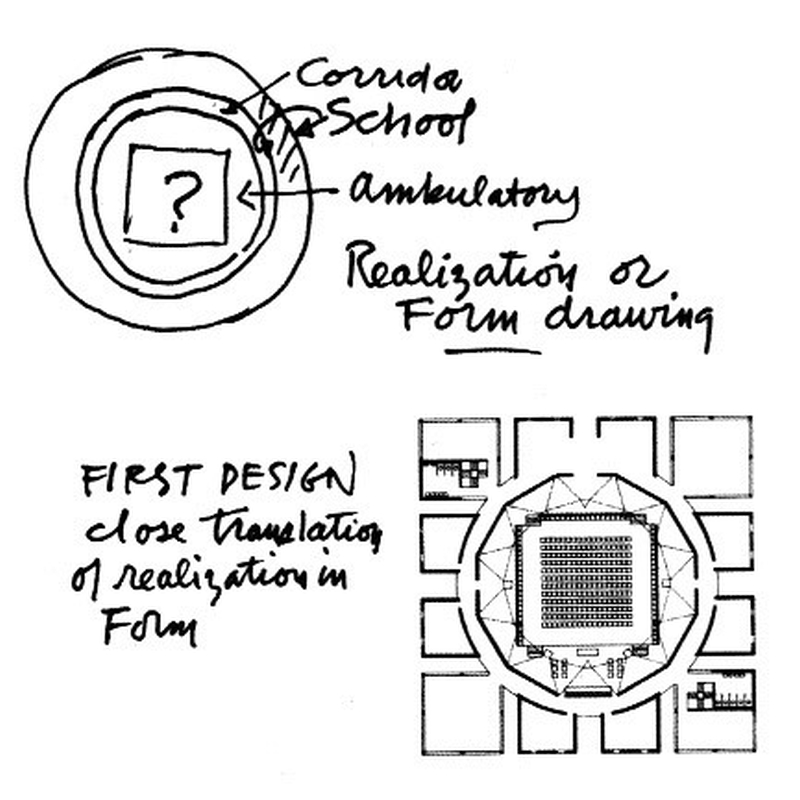

5-6 - Louis I. Kahn, Realization or form drawing and FIRST DRAFT, 1959.

Pencil on paper. Louis I. Collection. Kahn, University of Pennsylvania

and Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. (Dogan &

Zimring, 2002, p.50).

Fig.

7 - Louis I. Kahn, Explanatory diagram of the relationship between

spaces, 1961. Pencil on paper. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of

Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Fig.

8 - Louis I. Kahn, First Unitarian Church and School, Rochester, New

York, Final version: elevation, pencil on paper, 1961, 41 x 69.9 cm.

MoMa New York (407.1964). Last accessed October 20th, 2021

<https://www.moma.org/collection/works/565>.

Drawing and process

Regardless of the system of representation used, architectural

drawing can never fully collimate with the experience of the built

reality. Drawing, whether in its expressive dimension – the

sketch – or in its descriptive dimension – the

technical

and digital representation – can exclusively identify a

foreshadowing of the possible.

The materiality of drawing opens up new possibilities of

representation to identify the potentialities connected with it. As

Tomás Maldonado argued in his book Critica della

ragione informatica

[Critique of informatics reason] (1999): we need to overcome the

rhetoric of ‘technophobia’ and

‘technophilia’,

seeking to make the foundational statutes of the disciplines dialogue

with the evolutions and dynamics of society, building a living and open

environment capable of constructive co-evolution.

To identify the most appropriate tool to represent

architectural

design, one cannot operate in a predetermined manner but opt for a

choice that is open to the many variations that arise from time to

time. In this framework, besides being a collective and symbolic

language, drawing also expresses a subjective dimension.

As Francesco Cervellini reminds us, drawing constitutes the

main

place of design formation, «the irreplaceable place of design

formation»[1]

(2016, p. 759)

that offers an answer to the questions that architecture poses. A few

years earlier, Roberto de Rubertis also reminds us that drawing is:

«something more than a tool external to the designer,

something

other than an autonomous ‘tool’. On the contrary,

it

becomes an integrated ‘peripheral’ of him [...] It

becomes

a temporary archive of memory»[2]

(1992, p. 2).

It is continuing in the words of Paolo Giandebiaggi (2019),

who

defines drawing as an «intersection of reflection and memory

[that] is expressed in the course of ideation in four phases:

preparation, incubation, lighting and verification» (2019, p.

98). An incubation (the sketch) precedes the more purely descriptive

phases of the project (preliminary, final and executive design) and

often follows the moment of preparation (the survey). A moment, that of

the sketch, which intuitively gathers the information and stimuli that

the project will potentially develop.

The drawing for Luis I. Kahn

As it is easy to imagine, for Louis Isadore Kahn (1901-1974),

all

the stages involved in drawing as a design process are well defined and

present in his work. Suppose the more operational and descriptive

stages of design drawing are neglected. In that case, it can be said

that the relationship that the Estonian architect established with

drawing is an intimate one and, at the same time, one of potential

research.

As evidenced by Jan Hochstim’s (1991) catalogue of

most of

Kahn’s paintings and drawings, the investigative dimensions

of

Kahn’s drawings are multifaceted. One example is the

influences

of Louis Lozowick’s 1930s lithographs in determining his

early

style of representing reality. This phase of his formation highlights

the restlessness that characterized his early years of training and

forced him to draw on different sources of inspiration (Montes Serrano

& Galván Desvaux 2016). Also, considerable interest

is his

carnet de voyage and various drawings on board that testify to his

travels in Europe from 1928 to 1929 and to Italy, Greece, and Egypt

from 1950 to 1951 (Mansilla 2001) (Figg. 1, 2).

In these notebooks, the watercolour, pastel, and pencil

drawings

reveal rapid style changes, testifying to the simultaneous process

between an evolving way of drawing and an understanding of the

architectural shape of the individual objects represented. Reflections

later reformulated in Kahn’s subsequent architectures,

showing

how the work on the sketches achieved an extreme synthesis between

modernism and the historical form that distinguishes his work (Johnson

et al. 1996).

This second phase of his, related to travel drawing, provides

us

with an amazing body of work. Far from the rigour of his buildings,

these sketches are veiled by an air of romanticism that closely

resembles the work of artists who strongly inspired him, such as Henri

Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

With this experiences-drawing, Louis Kahn laid the foundation

for

what will be a close connection to his design experience. A potential

for listening, between drawing and design, continually fed by practice,

in an attempt, on the one hand, to define a style of his own in the

making and, on the other, to identify a way of researching what will be

new architecture.

Only from the 1960s onward does the search for the

‘form’ of architecture for Kahn become a

requirement. In

the text Beginnings: Louis I. Kahn’s philosophy of

architecture

(1984) by Alexandra Tyng – the architect’s daughter

–

the development of Kahn’s thought is also chronologically

illustrated in relation to previously unpublished correspondence and

notes.

In this regard, a diagram-scheme (Fig. 3) explains the

architect’s position very well. This manifests as the result

of

two opposite desires, the ‘Feeling’ and the

‘Tought’. Its realization, as a union of

‘Realism’ and ‘Philosophy’,

leads to

‘Form’, as a ‘Measurable

Project.’ A dream that

becomes reality that needs to translate all the mental images of

inspiration into tangible reality (Desvaux & Tordesillas 2017).

Concerning the form search, the dimension of drawing assumes a

key

role in interpreting his work. On the one hand are the drawings for

‘Feeling’, like the previously illustrated ones

made in the

early phase of his training and travels. On the other side are the

drawings for ‘Tought’. A thought that manifests

itself

through drawing, or as Franco Purini reminds us, «drawing is

thought itself, indeed it is the fundamental form-thought of the

architect, the elective place in which form appears, and in its purest

and most enduring essence»[3]

(2007, p. 33).

The words chosen in his diagram are not used symbolically, but

almost as theoretical constructs they are meant to represent.

‘Form’ is not strictly related to the physical

configuration of the represented object, but indicates a guiding tool

within which the project can unfold. Similarly,

‘Realization’, which precedes ‘Measurable

Project’, does not indicate the physical restitution of

something

in the world of the real; but is limited to the meaning that allows a

drawing to be transformed into something approaching an enlightened

concept. Kahn’s definition of

‘Realization’ is closer

to the sense of revealing something that was previously hidden and

unknown.

Kahn clarifies the relationship between

‘Form’, as a

guiding concept operated through drawing, and

‘Design’,

which emerged most clearly in the early 1960s. In the second period of

his design research, Kahn understood and used the interpretative power

of diagrams, which, in the book Louis I. Kahn: Conversations

With Students (1998), calls “form

drawing”.

‘Form’ becomes impersonal, an

inexpressible source,

underlying the subordinate order that in the project is transfigured

into the determination to want to be what architecture requires.

The architect’s habit of resorting to diagrams as

‘form-drawing’, or with form-thinking makes clear

his

desire to arrive at figuration through a series of steps, not

consequential, that accommodate a series from time to time of problems

internal to the project. With these diagrams, he interrogates

architecture, asking it what it wishes to become.

‘Form drawing’ as

form-thinking

Clarifying the use of Form drawing is

the two examples cited in an interview published in 1961 in issue seven

of Perspecta journal published by the Yale School

of Architecture. On the one hand, a project that was never built, the Goldberg

House (1959) in Rydal, Pennsylvania, and on the other, the

events of the First Unitarian Church (1959-1969)

in Rochester, New York State.

Using simple geometric shapes accompanied by textual

annotations

allows him to explore the layout of the various rooms. The example of

the house diagrams appears symbolic of the project’s

development,

which foreshadows the space’s nature even before its form is

fixed. The comparison between the square and the dynamic tension of the

diagonal challenges the orderly system of the regular form.

Similarly, at the first meeting with the congregation, Kahn

presented his famous Form drawing

diagram illustrating the concept he had developed for the spatial

configuration and functional diagram of the building. It impressed the

assembly so much that, given its expressive and persuasive power, it

succeeded in realizing the initial concept.

As is also evident in the drawings, the design of the First

Unitarian Church had several evolutionary stages. The first began in

July 1959 moment of the commission, and ended in December 1959 when

Kahn presented his first diagram drawing, entitled by the architect

himself “First Design” (Fig. 5). In the act of

describing

it, the architect himself tries to give the reasons for its conception

and first draft: «A square, the sanctuary, and a circle

around

the square which was the containment of an ambulatory. The ambulatory I

felt necessary because the Unitarian Church is made up of people who

have had previous beliefs» (Kahn 1961, pp. 14-15).

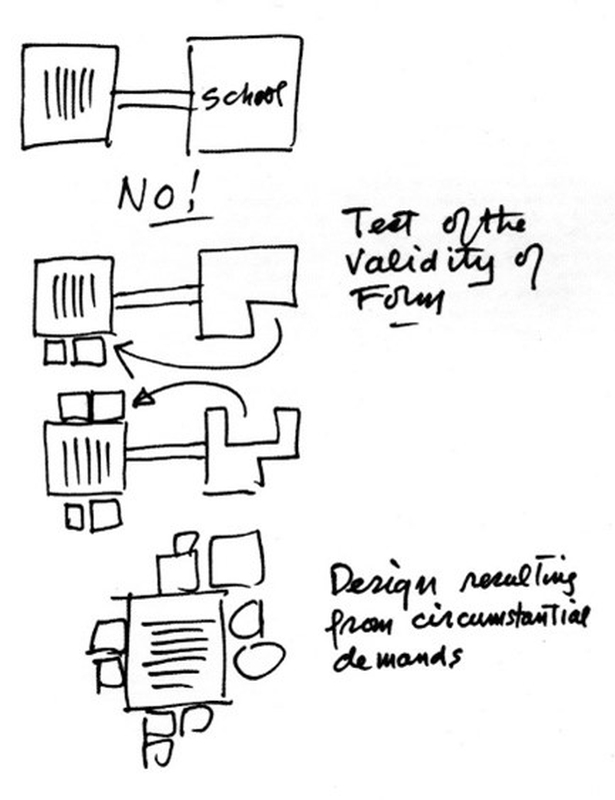

In the second phase, after the rejection of the first design,

Kahn

considered separating the school buildings from the church (Fig. 6).

The third phase began from the spring of 1960 until June 1961 (Fig. 7),

when the congregation approved Kahn’s final solution (Dogan

&

Zimring 2002).

Despite the different spatial solutions identified, it seems

puzzling how faithful the final design (Fig. 8) is to that concept

identified at the beginning.

Both cases examined show the synthetic ability to prefigure

form before identifying the final form of the building.

As László Mérö

states in his essay I limiti della razionalità. Intuizione,

logica e trance-logica [The

limits of rationality - Intuition, logic and trance-logic]:

«in

Western culture, a purely rational form of intelligence, based on

logic, has gained a dominant role [...] this kind of thinking [...] has

undoubtedly proved its raison d’être and

power»[4]

[Mérö, 2005, p. 8]. Likewise, however, it can be

said that there are other forms of knowledge.

In the drawing, the descriptive and prescriptive dimension, as

a

privileged quality, has predominated in our society. Whereas, the

investigation of the characteristics of indeterminacy of form, which

allow us to move in reading realities oscillating between what is and

what could be and which are not governable only through predetermined

rules or given prescriptions, has often been sidelined.

When associated with the qualities of indeterminacy, drawing

–

or rather than the project sketch – allows one to participate

in

that abstraction of form that shows the potential of the architecture

that will be or can be (Valentino 2020).

The value and purpose of the sketch for the

project

As illustrated above, in the first period of research and

education,

from 1931 to 1960, Kahn focused on the potential of drawing as a

thought-form that makes the ontology of architecture tangible; in the

second phase, from 1960 to 1974, he investigated the more spiritual

aspect of drawing for design.

The same author in The Value and Aim in Sketching

(Kahn

1931) reminds us of the importance of sketches in addressing design

problems. They do not constitute a crystallization of thoughts on paper

but are to be understood as questions awaiting answers for design

action.

In the last phase, Louis I. Kahn makes instrumental use of the

sketch. That is, he translates it into a device of inquiry. An

instrument that starts from what might be called a design process and

proceeds by diagrams. Diagrammatic drawings are very far from the

theory of diagrams that has always belonged to the culture of the

Modern Movement, where the design of space is resolved through

functional diagrams. Instead, Kahn’s diagrams – Form

drawings –

become a procedure for graphing spatial relationships between parts. An

ongoing interrogation of the potential of architecture.

Reading through the sketches of the architect’s two

works-the

– the Goldberg House (1959) and the First Unitarian Church

(1959-1969) –enables us to demonstrate the deep connection

between the use of drawing-diagrams and the completed work, where form

materializes through the figuration of its simple patterns.

Form drawing is, for all intents and

purposes, a

fundamental thought-form for the Estonian architect who takes on the

operational dimension to investigate potential forms of architecture. A

primal condition immediately brings a figuration, which in the later

stages of drawing allows a gradual approach to the final shape.

Today, in an age heavily influenced by the representation of

architecture through computer tools, the device of the sketch still

opens up possibilities for investigation. As Kahn’s lecture

shows

us, some occasions should be sought to increase the spectrum with which

the potential of drawing dimensions unfolds.

Notes

[1]

The text is a translation

by the author, the original one in Italian is as follows: “il

luogo insostituibile di formazione del progetto” (Cervellini

2016, p. 759).

[2]

The text is a translation

by the author, the original one in Italian is as follows:

“qualcosa di più che uno strumento esterno al

progettista,

qualcosa di diverso da un ‘utensile’ autonomo.

Diventa al

contrario una sua ‘periferica’ integrata

[…] Diventa

un archivio temporaneo della memoria” (de Rubertis 1992, p.

2).

[3]

The text is a translation

by the author, the original one in Italian is as follows: “il

disegno è pensiero esso stesso, anzi è la

forma-pensiero

fondamentale dell’architetto, il luogo elettivo nel quale la

forma appare, e nella sua essenza più pura e

durevole”

(Purini 2007, p. 33).

[4]

The text is a translation

by the author, the original one in Italian is as follows:

“nella

cultura occidentale, una forma puramente razio¬nale

dell’intelligenza, basata sulla logica, ha conquistato un

ruolo

dominante […] questo tipo di pensiero […] ha

senza dubbio

dimostrato la sua ragion d’essere e la sua potenza”

[Mérö 2005, p. 8].

References

CERVELLINI F. (2016) – “Il disegno come

luogo del progetto”. In: S. BERTOCCI e M. BINI (edited by), Le

ragioni del disegno. Gangemi Editore, Rome. 759-766.

DE RUBERTIS R. (1992) – “Editoriale - Il

disegno: cooprocessore della mente”. XY, 16, 2-3.

DESVAUX, N. G. E TORDESILLAS, A. ÁLVARO (2017)

–

“Louis Kahn, the Beginning of Architecture. Notes on Silence

and

Light”, diségno, 1,

083-092. doi: 10.26375/disegno.1.2017.10.

DOGAN, F., & ZIMRING, C. M. (2002) –

“Interaction of

programming and design: the first unitarian congregation of Rochester

and Louis I. Kahn”. Journal of Architectural Education,

56(1),

47-56.

GIANDEBIAGGI P. (2019) – “Disegno:

espressione creative”. XY, 1(1), 98-109. doi:

10.15168/xy.v1i1.20.

HOCHSTIM J. (1991) – The

paintings and sketches of Louis I. Kahn. Rizzoli. New York.

JOHNSON, E. J., LEWIS, M. J., E LIEBERMAN, R. (1996)

– Drawn from the source: The travel sketches of

Louis I. Kahn. MIT Press, Cambridge.

KAHN L. I. (1931) – “The Value

and Aim in Sketching”. T-Square Club Journal, 1(6), 19.

KAHN L. I. (1961) – “Louis

Kah”. Perspecta, 7, 9-28.

doi.org/10.2307/1566863

KAHN L. I. (1998) – Louis

I. Khan: Conversations with Students. Architecture at Rice,

Houston.

MALDONADO T. (1999) – Critica della

ragione informatica. Feltrinelli, Milan.

MANSILLA, L. M. (2001) – Apuntes de viaje

al interior del tiempo. Fundación Caja de

Arquitectos, Barcelona.

MONTES SERRANO C. e GALVÁN DESVAUX N. (2016)

–

“Las litografías de Louis Lozowick y su influencia

en

Louis Kahn”. EGA. Revista de expresión

gráfica

arquitectónica, 21(28), 92-99.

PURINI F. (2007) – Una lezione sul disegno.

Gangemi, Rome.

TYNG A. (1984) – Beginnings:

Louis I. Kahn’ s philosophy of architecture. J.

Wiley & Sons, New York.

VALENTINO M. (2020) – “Disegno

ambiguo e sagace

|Ambigous and Sagace Drawing”. In: A. Arena, M. Arena, R.G.

Brandolino, D. Colistra, G. Ginex, D. Mediati, S. Nucifora, &

P.

Raffa (edited by), UID 2020 - CONNETTERE. Un disegno per

annodare e tessere (pp.1434-1449). FrancoAngeli, Milan.