Fig.

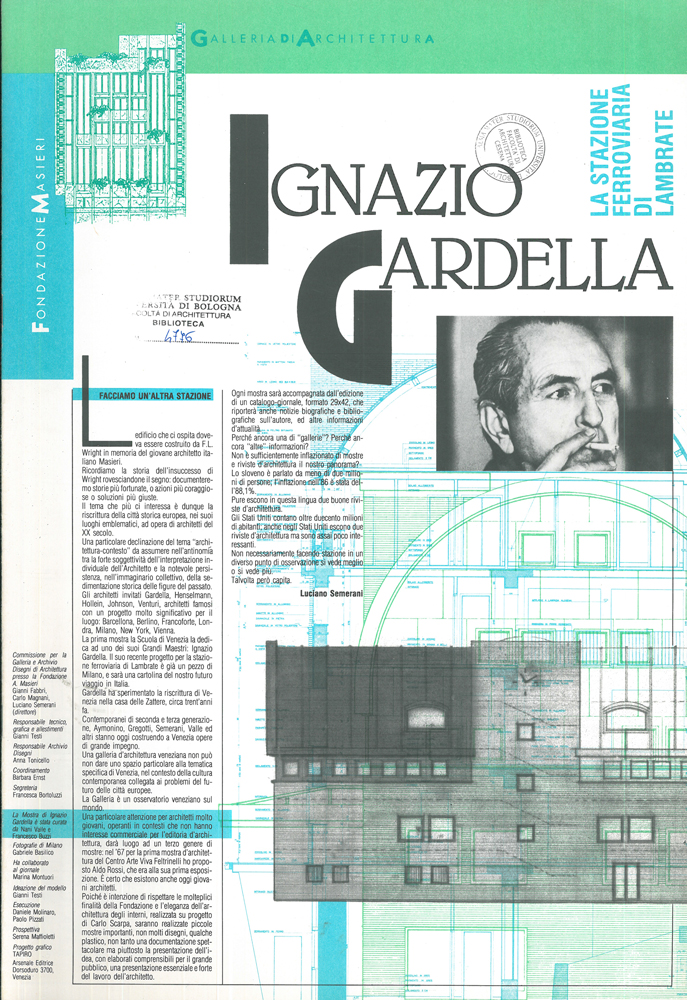

1 - Cover

of the paper of the Architecture Gallery with the first and the last

exhibition at the Masieri Foundation in Venice: Ignazio Gardella, the

railway station of Lambrate e Manuel de Solà Morales,

“El

Mol de La Fusta” in Barcelona.

Fig.

2 - Cover of Phalaris 0

Fig.

3 - Cover of Phalaris 1

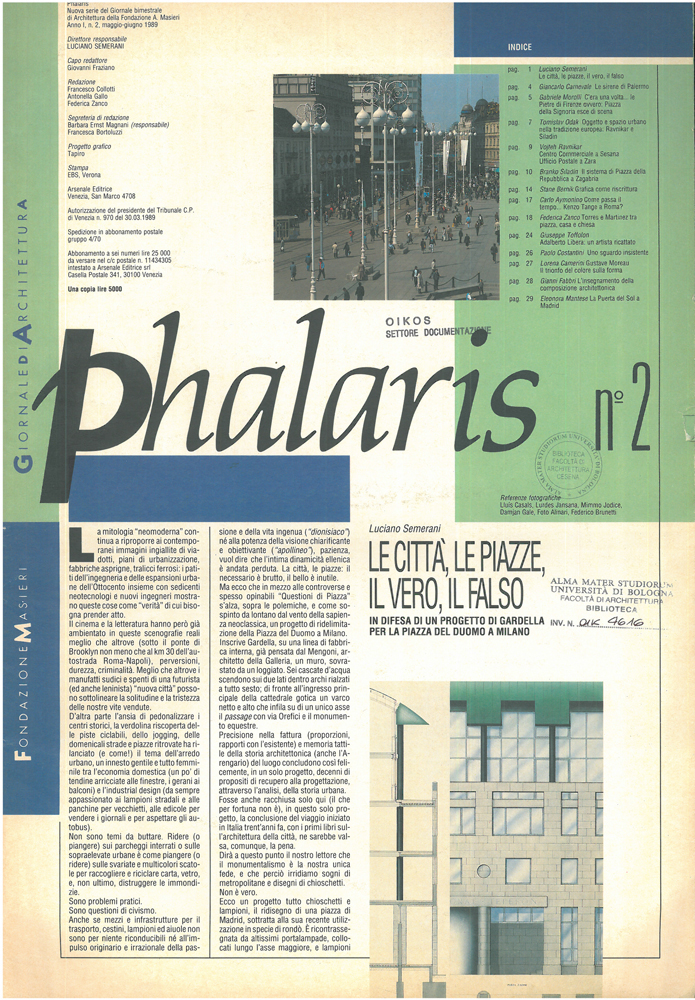

Fig.

4 - Cover of Phalaris 2

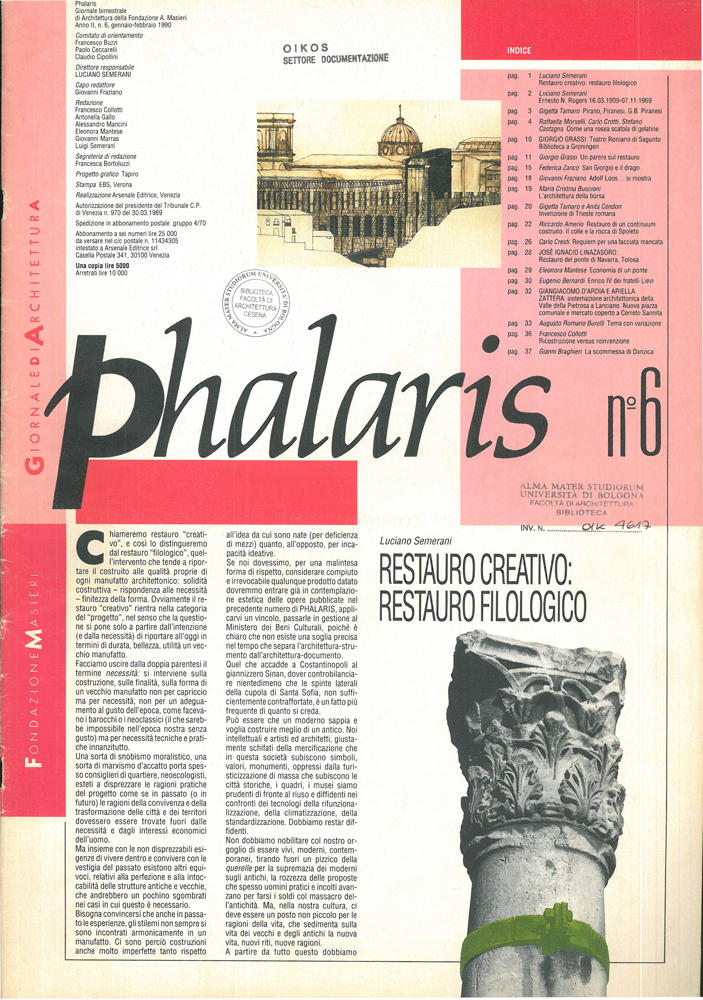

Fig.

5 - Cover of Phalaris 6 dedicated to Creative Restoration and Philological Restoration debate

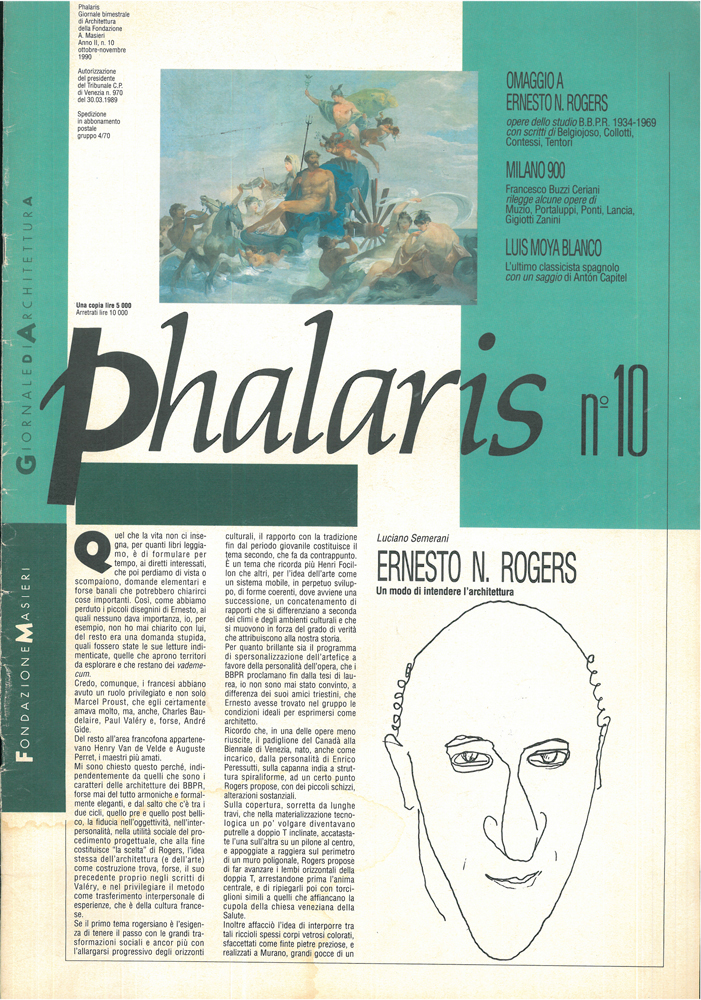

Fig.

6 - Cover of Phalaris 10

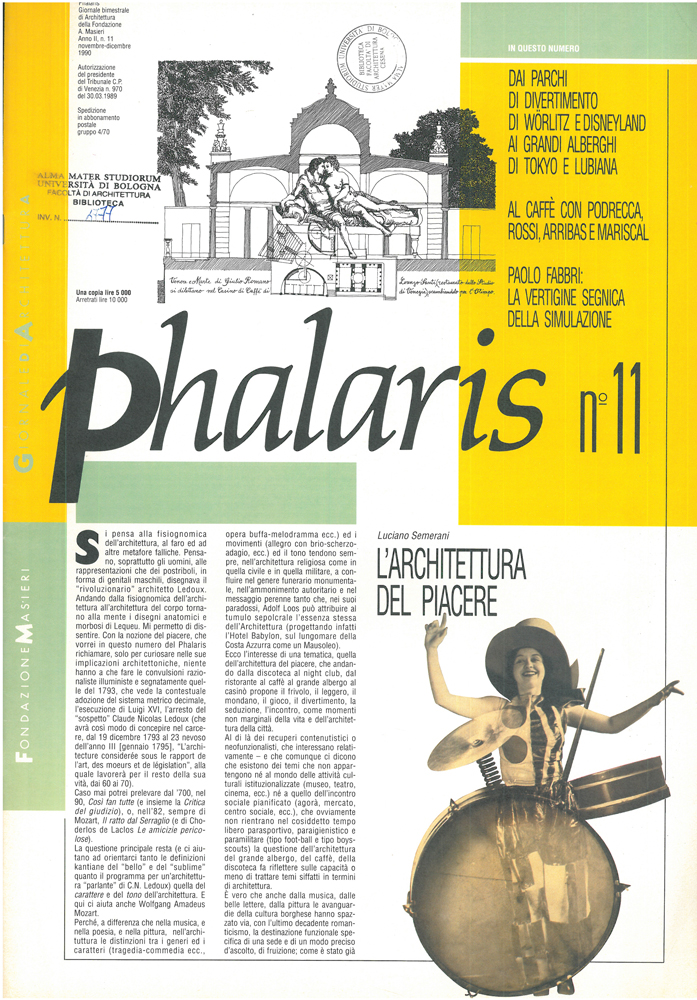

Fig.

7 - Cover of Phalaris 11 dedicated to Architecture of the Pleasure: amusement parks, caffè, hotels.

Fig.

8 - Double page (10-11) of Phalaris 11

Fig.

9 - Double page (20-21) of Phalaris 11

Fig.

10 - Page 11 of Phalaris 1 dedicated to the cinema

Fig.

11 - Phalaris 13 dedicated to the relationship between

USA and Europe in Architecture and other arts

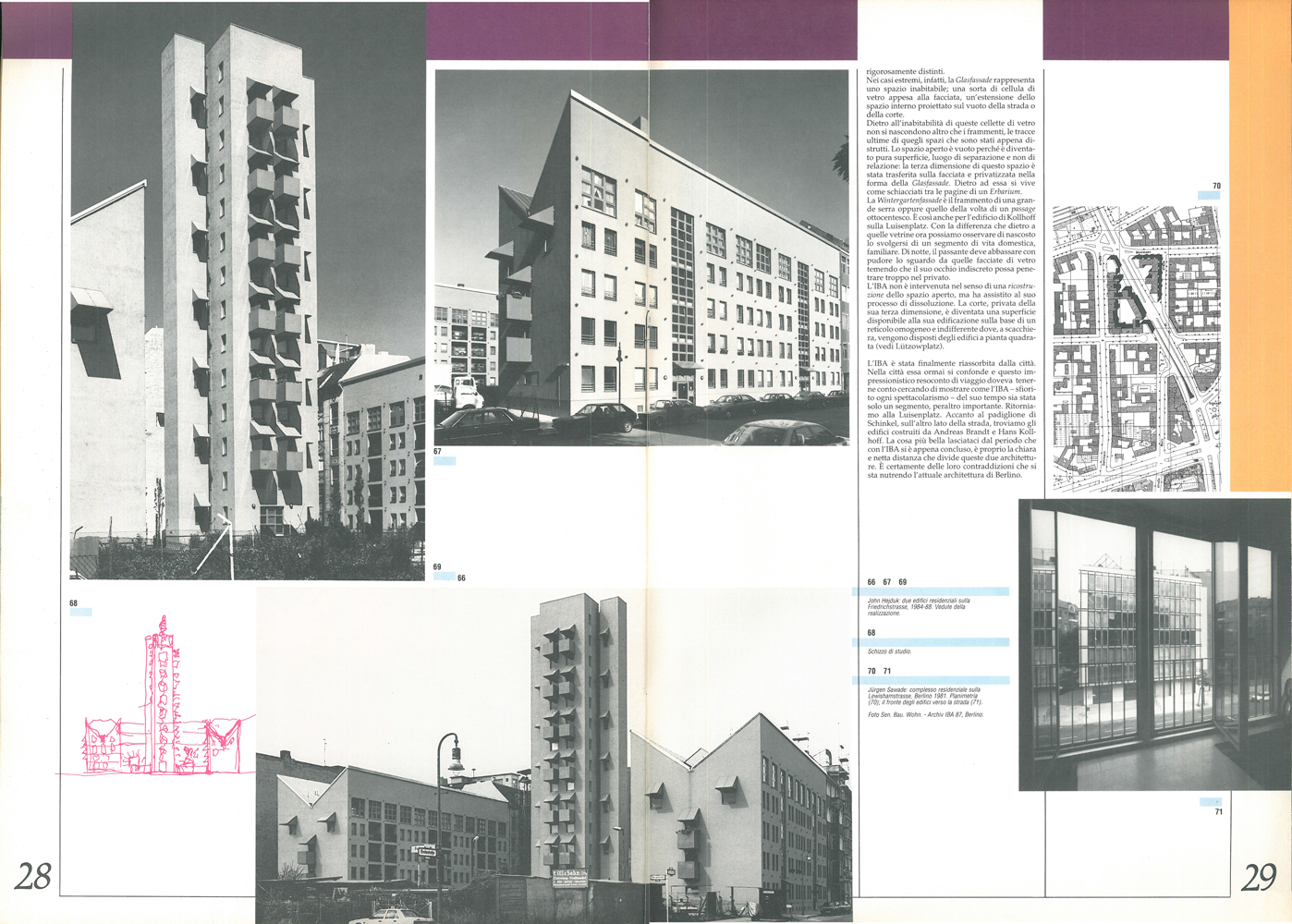

Fig.

12 - Double page (28-29) of Phalaris 13

Fig.

13 - Cover of Phalaris 15

Fig.

14 - Cover of Phalaris 16 dedicated to Mediterranean

architecture

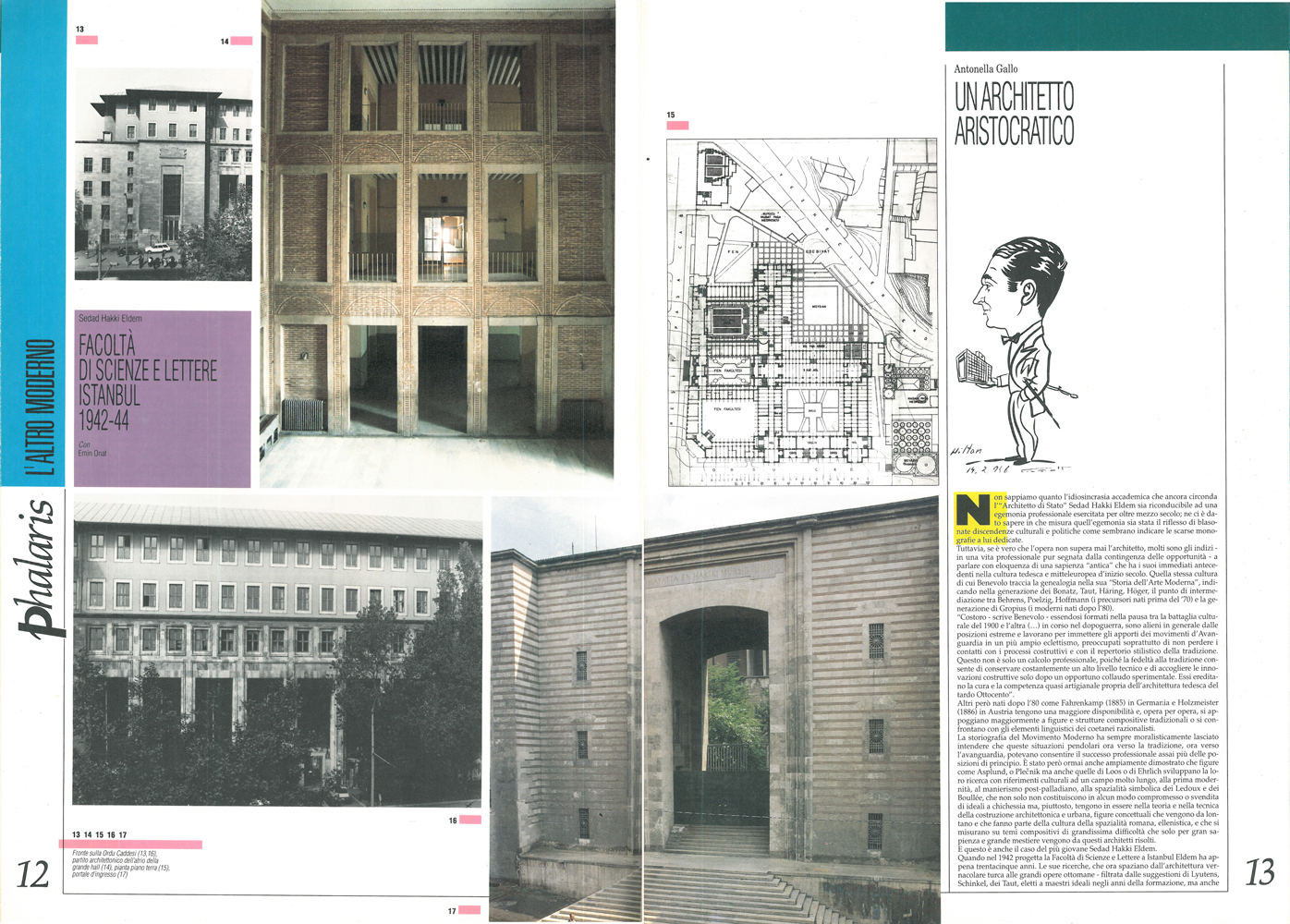

Fig.

15 - Double page (12-13) of Phalaris 16

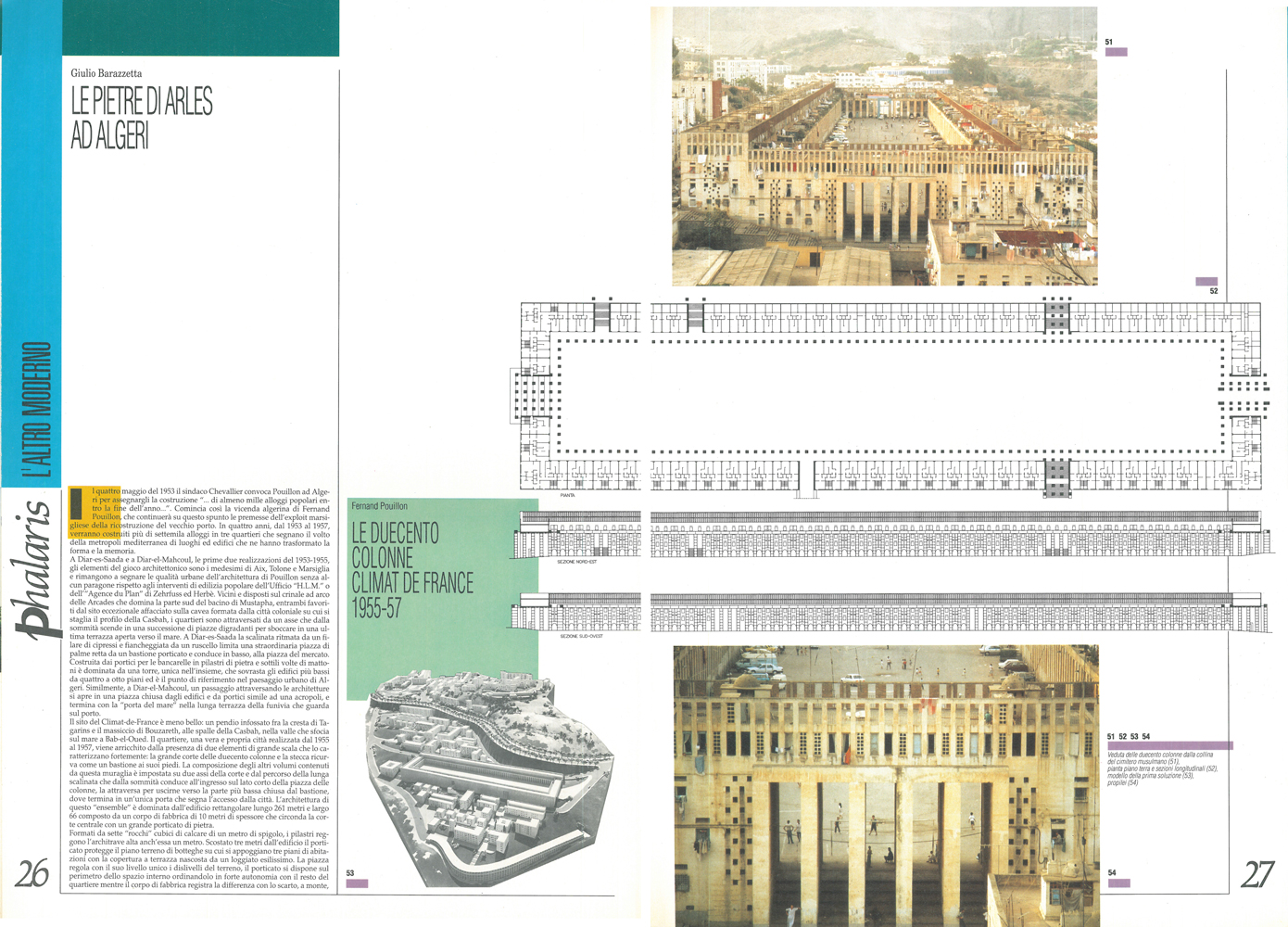

Fig.

16 - Double page (26-27) of Phalaris 16

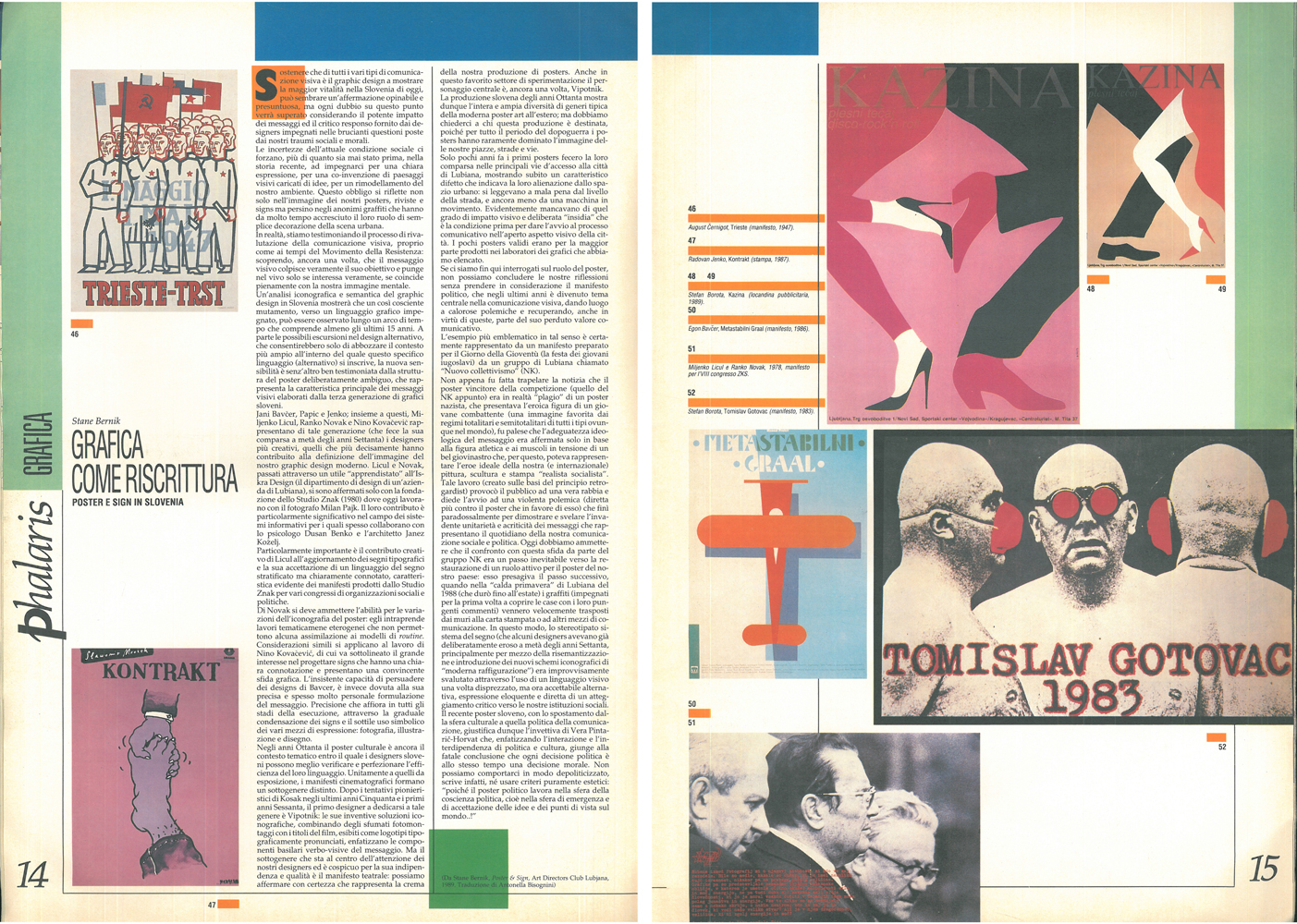

Fig.

17 - Double page of Phalaris 2