Peter Märkli: Things Around Us

Vincenzo Moschetti

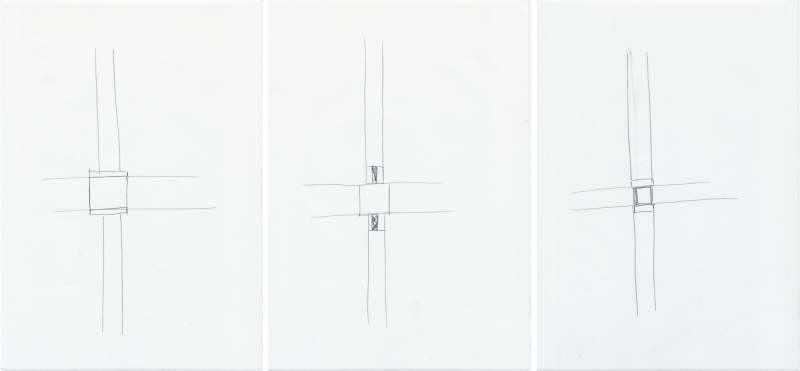

Fig.

1-2 - Peter Märkli, Drawings 1053 e 1050, pencil on paper,

210x297mm, 1980-1999. Courtesy: Studio Märkli.

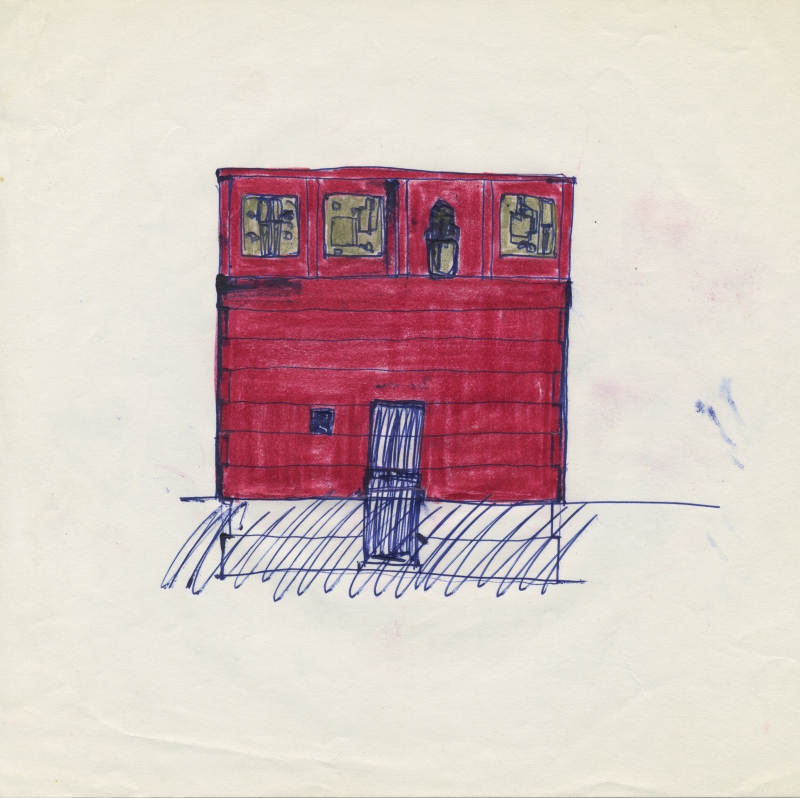

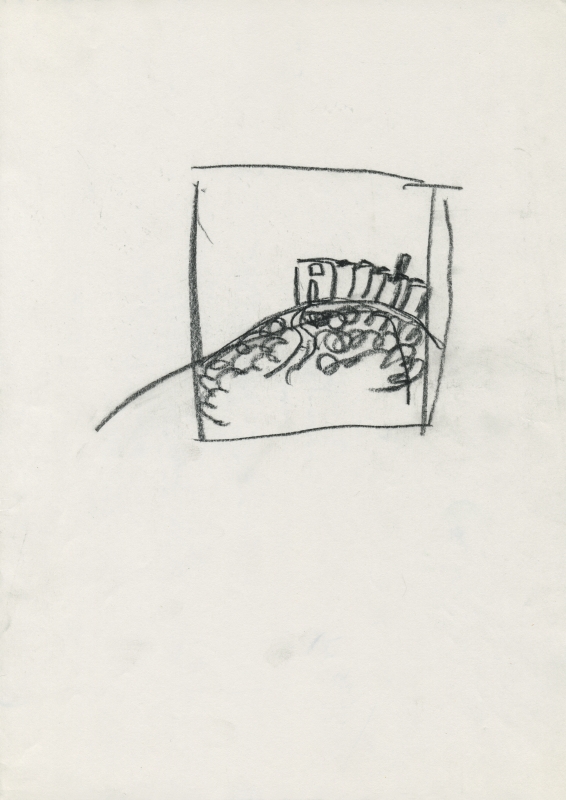

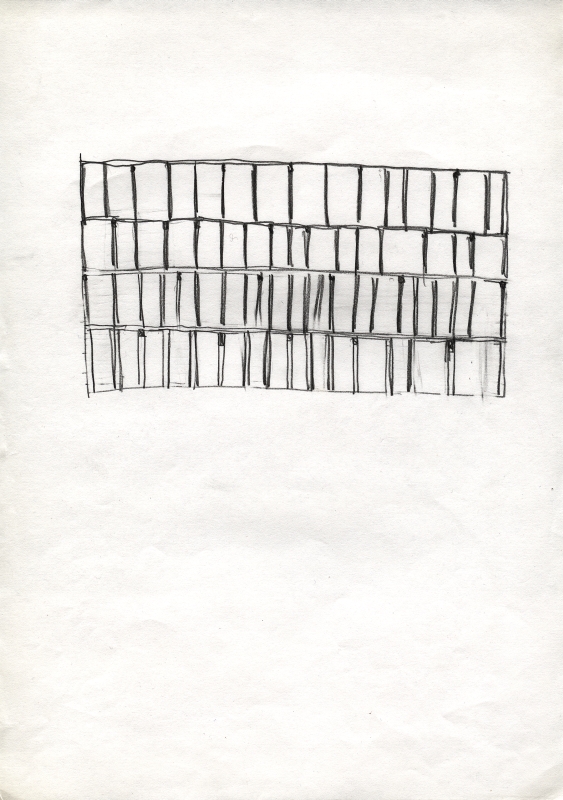

Fig.

3 - Peter Märkli, Drawing 1115, pencil and ballpoint pen on paper, 1980-1999. Courtesy: Studio Märkli.

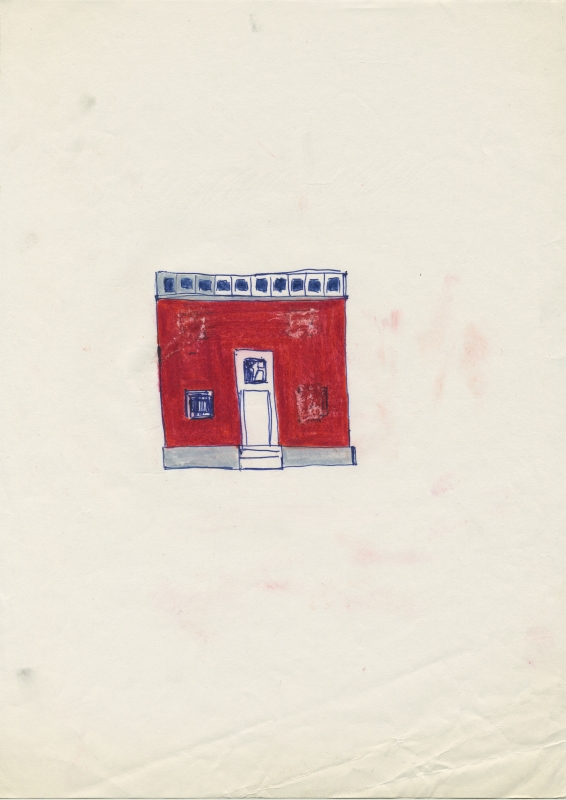

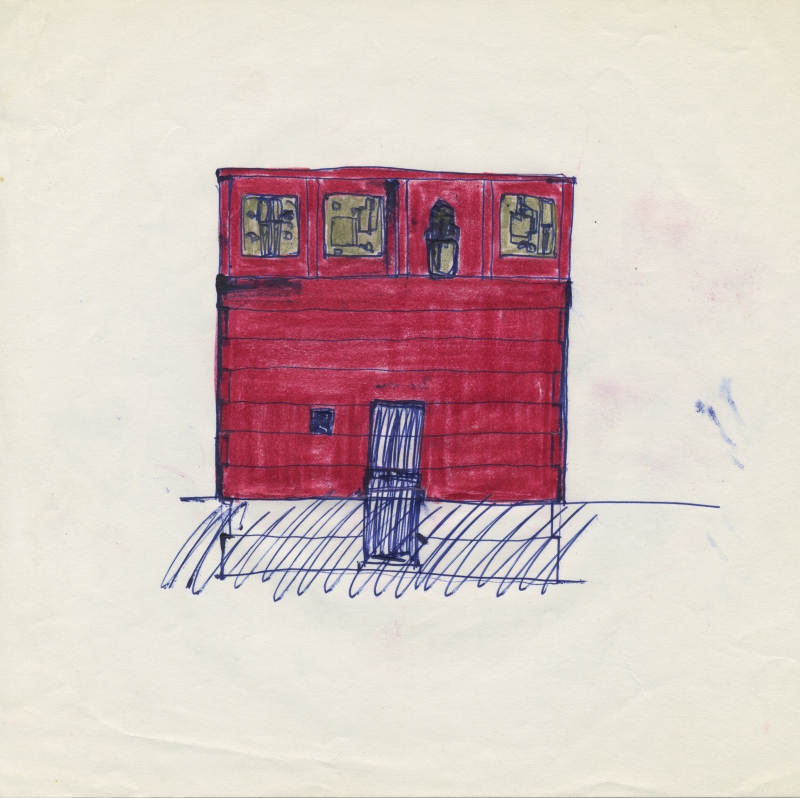

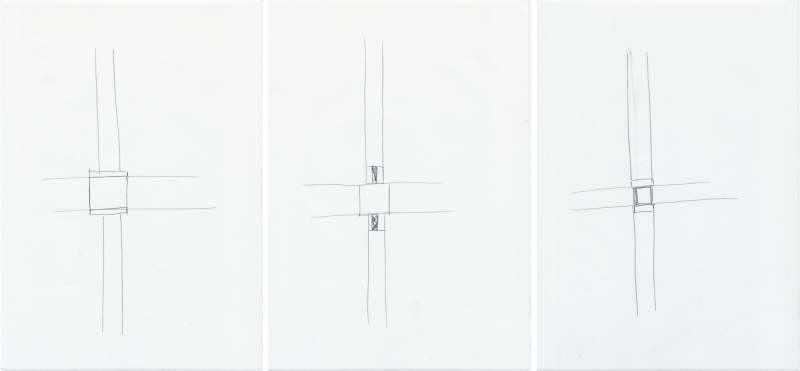

Fig.

4-5 - Peter Märkli, Drawing 1147, pencil and ballpoint pen on paper, 1980-1999.

(On the right), Casa Hobi, Sargans, 1983-2014. Courtesy:

Studio

Märkli.

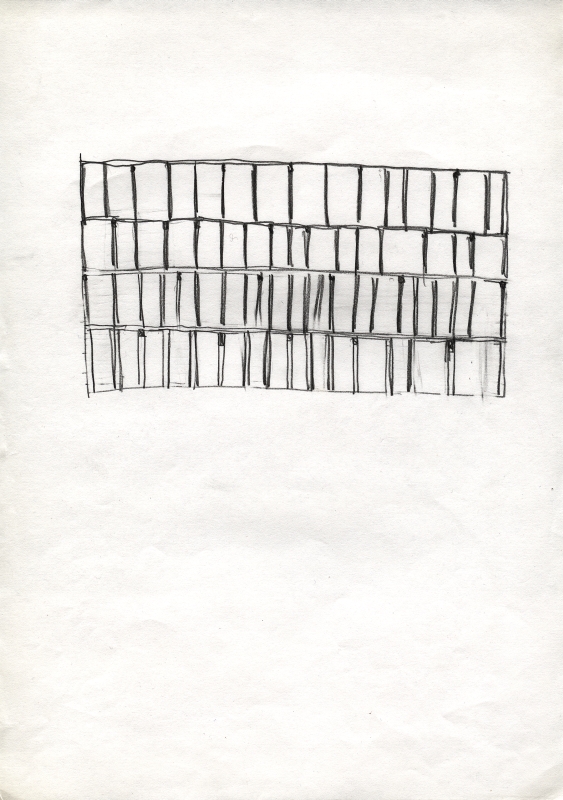

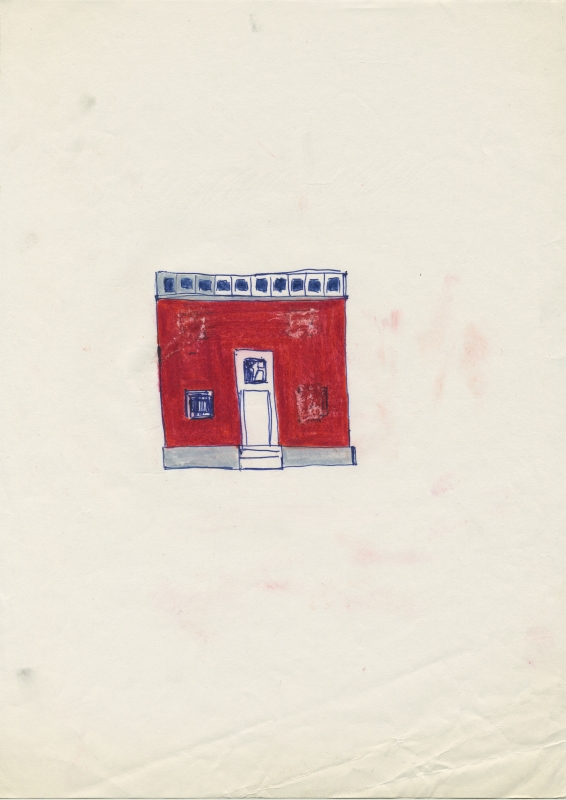

Fig.

6-7 - Peter Märkli, Drawing 1249, pencil on paper, 1980-1999.

(On the right), Mehrfamiliernhaus, Sargans, 1986. Courtesy: Studio

Märkli.

Fig.

8-9 - Peter Märkli, Drawing 2066, 2072 e 2083,

“Nodi”, pencil on paper, 2000-2019. Courtesy:

Studio Märkli. (Below), Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Thiene

(detail), Vicenza 1542; Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai

(detail), Firenze 1446, Peter Märkli, Synthes Headquarters

(detail), Solothurn 2011. Courtesy: Studio Märkli.

Fig.

10-12 (Above), Peter Märkli, Synthes Headquarters, Solothurn

2011.

Photo: Caroline Palla. (On the right), Peter

Märkli,

Synthes Headquarters, Solothurn 2011. Photo: Alexander Gempeler, Berna.

Alphabets

So these drawings refer back to the basic grammar of the

elements. (Märkli 2021)

The architectures of Peter Märkli are nestled within

the folds of the Swiss Alps according to a principle of boredom

in the sense given to this word by Alberto Moravia [1],

each time modifying the geography that hosts them. That is to say: by

offering the observer an updated alphabet within its syntax where

things that have disappeared sometimes return. The selection of the

volumes is a slow process, a sort of storyline that unfolds around the

letters of the composition. Expressed according to a series of

recollections inscribed within a set of continuous drawings, the

letters embark on an earnest quest to establish just a few elements

that acquire new shapes. Märkli’s drawings are flows

of a

sequence that he attempts to possess, to reconstruct, and to observe in

his projects within a system that is open but fixed by just a few marks

aimed at giving structure to a sort of collection rendered by

topographic images. In this sense he affirms that «I realized

that not only could these words be used to describe things

[…]

but also that it had, in literature, the power to describe feelings and

world views. […] I looked to the profane and the visual arts

and

started to observe and slowly learn the language. I simply began by

observing the grammar of our discipline» (Penn 2012).

In the ordering of his language, Märkli uses the

paradigm of

letters as the basis of a design alphabet, the phrases of which

–

at times very complex, and articulated at the intersection of multiple

focal points – introduce a reversal. This consequence can be

replicated within an authorial machanism where, tracing this mode of

expression back to its etymology, we discover that the architect is an expander

(Marini, Mengoni 2020), acting in such a way that this increase becomes

matter for experimentation for the study of a language

(Azzariti 2019) that serves to rewrite portions of geography through

professional practice. Thus, his practice is a sort of reduction

derived from a programmatic approach that allows us to recognize the

fact that «to be able to communicate, we have to know the

rules

of language» (Märkli 2008 (2006), p. 10).

The existence of an alphabetical code is the framework within

which

Märkli acts, comprising a system of tools of the discipline

that,

assembled together in the form of a drawing or of the project

“under construction”, configure phrases capable of

building

focal points that increase the established distances from territorial

boundaries in order to update their positions and operate by means of

prefigurations. In a manner similar to Ad Reinhardt’s use of

the

color black (Viray 2008), Märkli too – in the wake

of Max

Raphael – often uses drawings to explore the possibilities

through the opposition of two fields: on the one hand the solid mark,

«the indeterminate, the unbounded, the immaterial»

(Bronfen

1992, p. 9), and on the other hand the white of the paper, the

constant. This use of the mark thereby establishes not limits but deep,

distant movements in depth that the project will be able to experience

as an object of discussion and comment. The subject of this discussion

is a given place that the white of the paper, in the moment, does not

always specify.

Adventures

These drawings have to be small – they cannot be

large because

they are not about detailing. They’re explorations of

principles.

They capture the essence of things in few lines that nevertheless

encapsulate a lot of possibilities.(Märkli 2021)

Märkli’s research defines an imagery that

since his years

at ETH in Zurich has operated along the lines of the adventure. His

insistence on displaying a «unique event […]

unexpected

case» [2]

serves to create the

territory within which he can observe his production and position his

letters in order to achieve the modernization of the discipline

proposed by him with respect to a territory characterized by severe

shadows. The fundamental idea at the base of the operations between

drawing and project is that of «tout ce qu’on

invente

est vrai» (Flaubert 1998), where representation, above all in

the

form of “sketches”, long before construction,

establishes a

process of rewriting and programming, of pillages apparently from other

worlds. Already from the start, the relationship between drawing and

project seems like a program where the expression can be recognized

according to which «our earliest ancestors built their huts

only

after having conceived their image» (Boullée 1967,

p. 55).

Märkli’s drawings offer a basic course on

comparative

anatomy, much like what is taught in the first years of veterinary

sciences. The comparison between the structures of the various groups

establishes a possible re-signification of the content, applicable to

both the representation and the architectural project. The

architect’s gaze enters into the rooms of the drawing with

its

volumes rendered in dual dimensions, spaces that are only apparently

enclosed by the orthogonal boundaries of the sheet of paper, where

black lines emphasize connections in which the architecture is

presented as an action. The figure of the room is an illusory strategy

that allows the imaginary world to be rendered as both visible and

concrete, while the drawing permits the production of inhabitable

tensions in which the play of mirrors between the various geographies

and worlds builds complexities on several levels. «By

connecting

the regular and irregular, Peter Märkli could create order,

organized forms and immersive space. Inside the work, through Peter

Märkli’s eye, I could move around and feel my

presence in

the world, either in silence or with a pleasant whisper. Peter

Märkli’s ‘eye’ is

‘I’» (Viray

2015, p. 114). This being inside is the lens

that serves to

activate the reconstruction process, not something that has to do with

ruins so much as a program that in reality observes a genealogy for making

architecture.

The drawing, with its “rooms”, anticipates the

construction

of the building without having to observe the laws of statics beyond

those required by the representation itself.

Not all of the drawings will come to fruition; they are in

part exempla,

experiments of an open construction site that still feels the need for

figurative representation to make the project a reality. Arranged

together, indeed they represent adventures, established by means of

marks that are none other than narrative practices where the inversion

between light and shadow, and the testing of colors and materials, and

of grades and proportions, connects the parts of the worlds from which

they originate. They are questions that move the design investigation

away from predefined distances, making it possible to verify the

declaration according to which Märkli, like

«Shakespeare

approximates the remote, and familiarizes the wonderful; the event

which he represents will not happen, but if it were possible, its

effects would probably be such as he has assigned; and it may be said,

that he has not only shewn human nature as it acts in real exigencies,

but as it would be found in trials, to which it cannot be

exposed» (Johnson 1765, pp. XI-XII).

The drawings of Peter Märkli thus cannot be considered

exclusively

as an exploratory tool so much as a design event in itself, where the

process of spolia in re is substituted, within

the territory of the sheet of paper, by that of spolia in se,

effectively translating a principal of auctoritas

in the field of architecture [3].

The composition then undergoes reversals in which the continuity of the

ancient is assumed by the reappearance of color, in a correction of

Winckelmann’s interpretation, thus embodying the return of a

compositional tool that had been superimposed over the stones of the

ancient temples before its disappearance. The use of color is the

unique and unexpected event of the adventure into which the architect

invites the observer, where the causes and effects of a time (that of

architecture, which sees no pauses but only returns) become immersed in

a collection and repositioned. Based on the idea that the animal

structures of today are derived from those that came before them,

biologists use scalpels and microscopes to access the concrete world of

vertebrates. Märkli uses sheets of A4 paper and colored

pencils to

construct the space of architecture in an inquisitive process of

verification, analogous to that of the veterinary scientists but born

of his hands-on experience of teaching architecture.

Architectures

The mechanisms traversed mark the existence of lists in which

the

positioning of the elements of architecture, treated as letters of an

alphabet, permits the discovery, through the practice of drawing, of

the existence of an updatable grammatical syntax. Upon entering

Märkli’s architectural studio in Zürich, as

if in a

dizzying list of things (Eco 2009), one sees that «his modus

operandi is made explicit by the drawing board with Mayline parallel

motion […] books lie open on the floor, sketches and

drawings

are pinned to the walls» (Chipperfield 2020, p. 22). His

studio

expresses the need to remain within, as if in a density within which

«the drawings become the place where the ideas are found and

formulated» (Chipperfield 2020, p. 20), thereby defining an

operational centrality.

The territory of representation becomes, for Märkli,

the field

on which to let flow and prefigure the physicality of architecture and

its making. Paper architectures, before reaching the ground, thus

negotiate an inventive possibility with geography and time. Their

relationship with history translates into one with multiple

“stories,” and drawing becomes a project in itself.

Märkli, therefore, has the merit of working on a dual track,

that

of paper and that of the construction site. He composes devices

(Deleuze 1989) by means of these architectures, identifying with what

will become the “structures” of the finished

project and of

the inhabited space.

Märkli’s building for the European

headquarters of the

Synthes company in Solothurn, Switzerland, completed in 2011, is an

investigation of history through drawings. A series of lines and

surfaces sunk into the paper gave structure, long before the concrete

was poured, to the entire workspace. In his graphic execution, the

architect’s questions traverse much of the history of

architecture. Summarized in a collection of images in which the

façade of Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai is overlaid

onto that

of Palladio’s Palazzo Thiene, they led to the creation of a

solution that can be defined by the term node.

His executive

accuracy is thus the result of a crossroads where «the

joining of

the horizontal and the vertical became a preoccupation»

(Johnston

2017, p. 120), and where both the construction of the work and its

structural solutions are discussed within the two-dimensionality of the

sheet of paper. Horizontal areas, devoid of thickness, anticipate the

verticality of the project, where the presence of black marks in the

field of the A4-size paper compiles practical questions by depriving

itself of the regularity of measurements. The absence of right angles

does not lead to the abandonment of geometric rule, of a logical and

proportional construction; on the contrary, it demonstrates a knowledge

of the disciplinary codes of the profession, which emerge in the guise

of objects, elements and colors aimed at solving the entire

composition. In this sense, Synthes joins the logical succession

rendered by the architect on paper, where, from the Renaissance onward,

things have re-emerged with the reintroduction of a letter A, which has

nevertheless been able to update the positions, bringing together the

experiments of a destiny that can produce new figures from copied

objects.

The junction between the vertical and horizontal systems is

highlighted by the presence of a square element made of exposed

concrete: the knot, an important synthesis that Märkli finally

reaches after much research and after a thorough investigation of the

ability to reconstruct an entire network of relationships based on a

simple allusion to partial formal clues. This research finds its origin

in the columns of Olgiati’s Radulff house, in

Palladio’s

moulding designs, and makes its way through to his first houses with

Josephsohn’s reliefs above the pillars, finally reaching

maximum

abstraction in the junction/knot of the Picassohaus in Basel. One of

the images that was used to illustrate the project presented two

different architectural references: Palazzo Thiene – in which

the

distinction between vertical (columns), horizontal (entablature), and

transitional (capitals) elements is rather canonical – and

Palazzo Rucellai – where instead this distinction tends to

diminish. (Azzariti 2019, p. 111)

The façade is a process of re-signification of this

design

program, where the architecture asks questions to which the building

site attempts to respond in an attempt to verify the existence of a

drawing that is not only visible but also, more importantly, is

traversable. The node – an adept advancement of the

sculptural

practices learned in the studio of Hans Josephsohn [4]

– announces the work performed by the project in horizontal

section, determined by a pattern of dots, and in vertical section,

where the pillars meet the floors on which the rooms are placed. The

presence of the architectural order signals the insertion of a double

register that addresses multiple scalar dimensions: the first order,

“giant” at 22 meters high, seems to want to

position itself

in a territorial paradigm, while the second order, the interior one,

speaks to the lives of human beings. This distinction is the discussion

of an executive palimpsest of graphic investigations in which geometric

grids, orthogonal to each other, verify the grammar between the primary

and secondary objects that emerge or are submerged by the chosen syntax.

If, in light of this fact, the pillar appears autonomous, the

drawings demonstrate that it is instead a “victim”

of a

heteronomy that was already reflecting on a dual track of

considerations from the time of the apartment building in Sargans

(1986). The mass of that building – primitive in terms of

dimensions – positioned itself as a comment on the

surrounding

mountains, introducing a narration of darkness and cavities; in

Solothurn, the comments have continued, responding to the geography

with a contemporaneity that does not renounce the archaism of 1986 but

which sees in it a possibility of proceeding towards new dimensions of

things.

The drawing is also a thing. Once the hand has traced onto the

paper

– the drawing has a physical presence, its own presence. It

has a

“Gestalt” and comes forward

towards the viewer.

This form of its own is also beside its originating image, impulse,

idea, search or context. It is a mark. It makes a mark.(Hatz 2015, p.

146)

The system of drawings that preceded the project, and that

precede

all of Märkli’s architecture, reveals the presence

of a

method that seeks the existence of a language that can establish itself

as a graphic form of trial and error, thereby becoming constructed

matter. Within the lines produced by his displacements, Märkli

processes oscillations [5] capable

of clarifying that those black marks are profound presences, with

as-yet undefined but clear contours with respect to a linguistics of

architecture. The objects that emerge are the result of a migration

that collects clues on paper, where the project, in this case Synthes,

but even before that Sargans, is the solution to an enigma in which the

use of such fundamental elements as plinths, columns, and pilasters,

that is the letters of the compositional alphabet, like a letter A,

allows Märkli to found new geographies through the

construction

and re-elaboration of things positioned around

us, with space as the reference.

The author wishes to thank Peter Märkli and Theresa

Hacker for

their wonderful collaboration in creating and building this paper.

Thanks to Alexander Gempeler e Caroline Palla for the images.

Notes

[1]

«Märkli’s

working procedures, however, are self-induced and are in part a

deliberate reaction to the prevalent notion of the

architect’s

studio as an office machine. Among the writings of Alberto Moravia, one

of a host of influential twentieth-century Italian writers well known

to Märkli, is a novel published in 1960, entitled La

noia. Moravia defines through his protagonist the concept of

noia,

boredom: ‘The feeling of boredom originates for me in a senso

of

absurdity of a reality which is insufficient, or anyhow unable, to

convince me of its own effective existence… For me,

therefore,

boredom is not only the inability to escape from myself but is also the

consciousness that theoretically I might be able to disengage myself

from it thanks to a miracle of some sort’. Most people think

of

boredom as the opposite of amusement, but for Moravia this is not the

case. In fact, for him boredom comes to resemble amusement

[…].

In the same way that the interruption of the electric current

highlights the artefacts of Moravia’s fictional house,

distraction leads to a closer reading of things» (Mostafavi

2002,

p. 8).

[2]

Avventura, entry in Devoto G., Oli G.C. (2000), Il

dizionario della lingua italiana, Le Monnier, Florence, p.

193.

[3]

«Spolia in re

(through the physical transportation of ancient objects –

sculpture, architectural elements, and gems – and their

insertion

in a new context) and spolia in se (objects created

ex novo,

but based on ancient models) are thus two sides of the same coin: in

its new context, the antiquity is no longer perceptible in its

entirety, yet it is clearly defined and endowed with meaning. This

sense is embodied and translated into the principal of

auctoritas,

which surrounds the handed-down antiquities like an aura. On the one

hand it is defined by their presence, visibility, and accessibility,

and on the other by the (relative) lack of corresponding knowledge and

technical abilities, and even more by the awareness or sense of that

lack» S. Settis, Continuità

dell’antico, entry in AA.VV. (1994) –

Enciclopedia dell’arte antica, classica e orientale,

Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, founded by Giovanni Treccani,

Rome, 256.

[4]

It is as if these nodes had

taken on an ulterior precision or preciseness with respect to what

preceded them. Citing Kubelik’s studies, Märkli has

repeatedly pointed out that Palladio’s elements were also

already

present in Venetian architecture, and that they took on greater

precision, for example, in his designs of villas. See Kubelik M. (1986)

– “Palladio’s Villas in the Tradition of

the Veneto

Farm”. Assemblage, 1, 90-115.

[5] «What happens if the images [that is the maps]

begin to oscillate?» Wittgenstein L. (1971) – Osservazioni

sopra i fondamenti della matematica. Einaudi, Turin, 183;

original ed: Wittgenstein L. (1956) – Bemerkungen

über die Grundlagen der Mathematik. Blackwell,

Oxford.

References

AGAMBEN G. (1977) – Stanze. La parola e

il fantasma nella cultura occidentale. Einaudi, Turin.

AZZARITI G. (2019) – In search of a

language. A journey into Peter Märkli's imaginary /

À la recherche d’un langage. Voyage

dans l’imaginaire de Peter Märkli, CosaMentale,

Marseille.

BOULLÉE E.L. (1967) – Architettura.

Saggio sull’arte.

Introduction by A. Rossi. Marsilio, Padua.

BRONFEN E. (1992) – Over Her Dead Body:

Death, Feminity and the Aesthetic. University of Manchester

Press, Manchester.

CHIPPERFIELD D. (2020) – “La buona pratica

/ Good Practice. Peter Märkli”. Domus, 1043, 18-25.

ECO U. (2009) – Vertigine della lista.

Bompiani, Milan.

FLAUBERT G. (1998) – Correspondances (or.

ed. 1853), édition établie,

présentée et annotée par J. Bruneau.

Gallimard, Paris.

HATZ E. (2015) – “Making a mark

/ Zeichen setzen”. In: F. Don, C. Mion (edited by),

Peter Märkli: Drawings / Zeichnungen. Quart

Verlag, Luzern, 146-151.

IMOBERDORF C. (2016) – Märkli.

Professur für Architektur an der ETH Zürich | Chair

of Architecture at the ETH Zurich. Themen /

Semesterarbeiten | Topics / Semester Works. 2002-2015. gta

Verlag, Zürich.

JOHNSON S. (1765) – Preface to his

Edition of Shakespear’s Plays.

J. & R. Tonson, H. Woodfall, J. Rivington, R. Baldwin, L.

Hawes,

Clark and Collins, T. Longman, W. Johnston, T. Caslon, C. Corbet, T.

Lownds, and the executors of B. Dodd, London.

JOHNSTON P. (edited by) (2017) – Everything

one invents is true. The Architecture of Peter Märkli.

Quart Verlag, Luzern.

MARINI S., MENGONI A. (2020) –

“Materia-autore /

Author-Matter”. Vesper. Rivista di architettura, arti e

teoria /

Journal of Architecture, Arts & Theory, 2, 8-11.

MÄRKLI P. (2008) – “On Ancient

Architecture.

Fragment of a lecture at London Metropolitan University, November 2006

by Peter Märkli”. A+U. Architecture and Urbanism,

Peter

Märkli: Craft of Architecture, 448, January, 10-15.

MÄRKLI P. (2021) – Mein Stoff

für Fassaden / My Facade Materiale. [online]

Disponibile a:

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2g5581w8Js> [Accessed

by 22 October 2021]

MOSTAFAVI M. (edited by) (2002) – Approximations:

the Architecture of Peter Märkli. Architectural

Association Publications, London.

PENN S. (2012) – Interview to Peter

Märkli for the AE Foundation for Architecture + Education.

[online] Disponibile a:

<https://aefoundation.co.uk/Peter-Markli> [Accessed by 16

October 2021]

PORTOGHESI P. (2016) – “Combinando cose

lontane /

Combining distant things”. Techne. Journal of Technology for

Architecture and Environment, 12, 40-42.

VIRAY E. (2008) – “Peter Märkli,

Structure Form

Emotion”. A+U. Architecture and Urbanism, Peter

Märkli:

Craft of Architecture, 448, January, 60-67.

VIRAY E. (2015) – “Peter

Märkli’s eye / Peter Märkli Auge”.

In: F. Don, C. Mion (edited by), Peter Märkli:

Drawings / Zeichnungen, Quart Verlag, Luzern, 112-115.