The drawing of the territory’s form

Luigi Savio Margagliotta

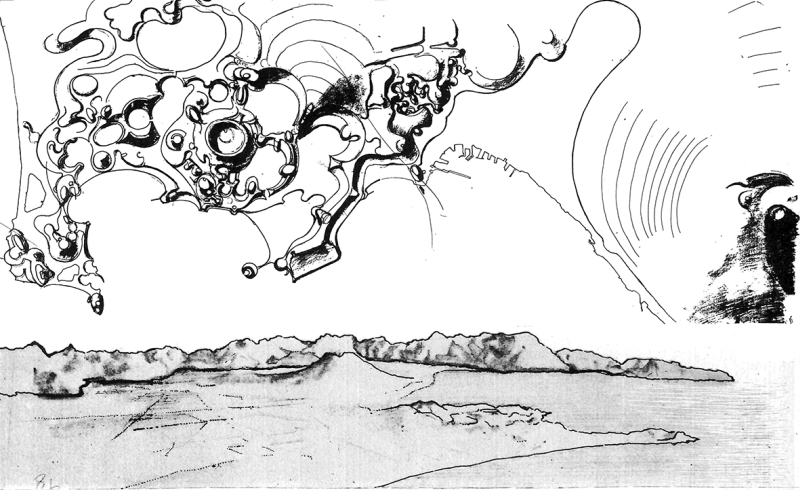

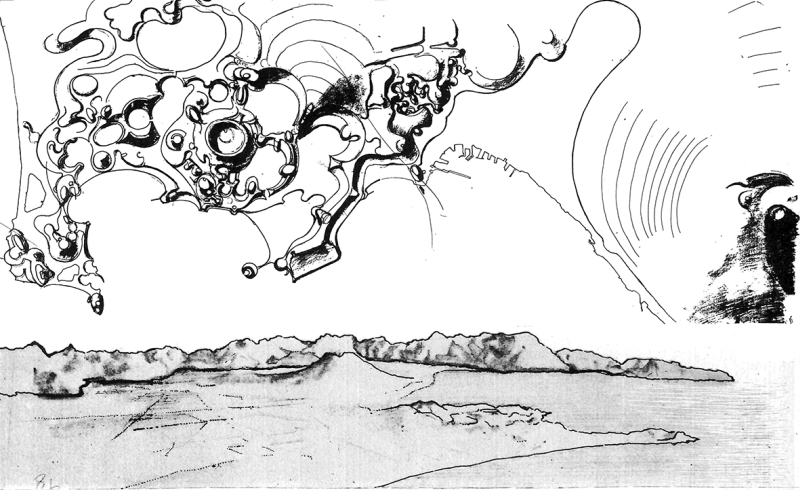

Fig.

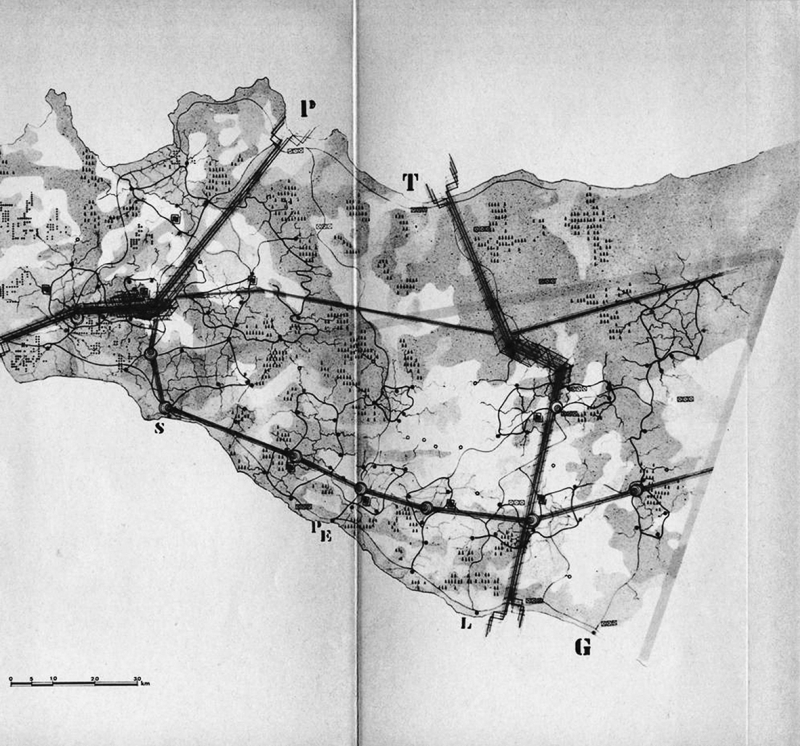

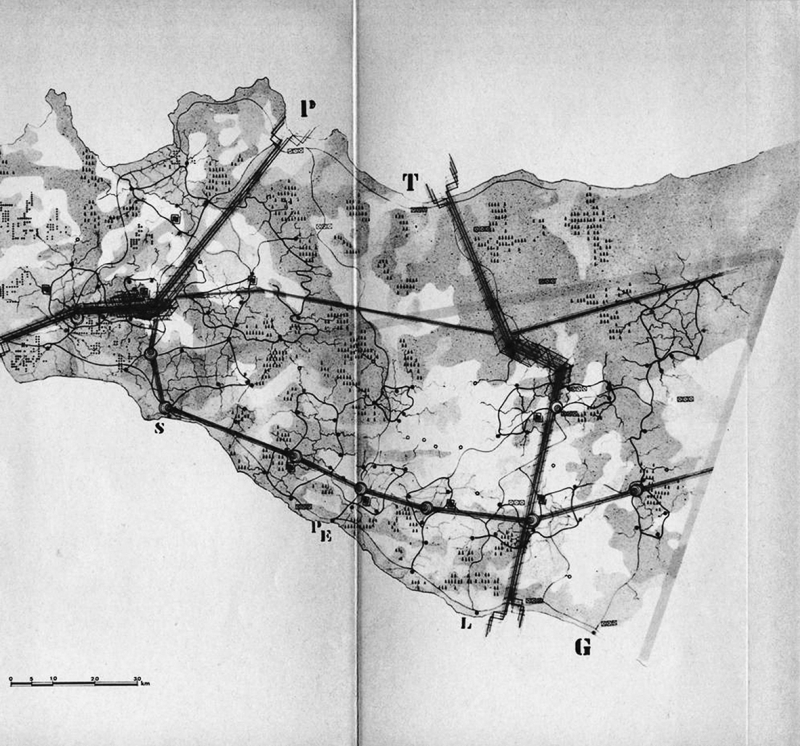

1 - Salvatore Bisogni and Agostino Renna, Introduction to the Naples

urban design problems. Spatial interpretation of the orographic

condition of the area, 1963-64.

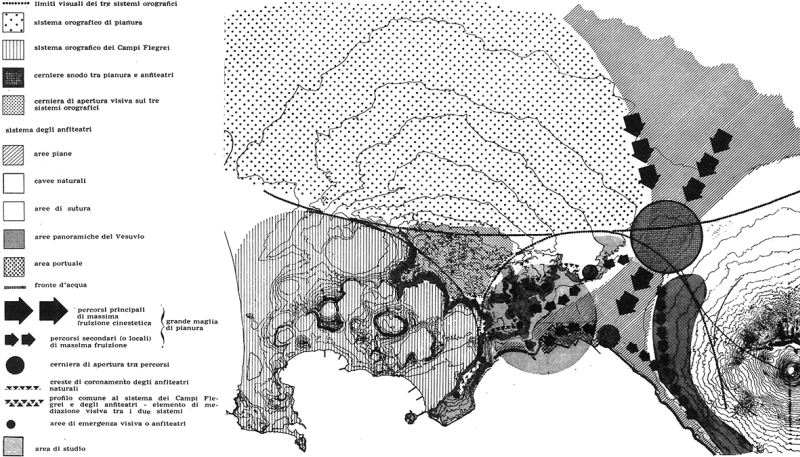

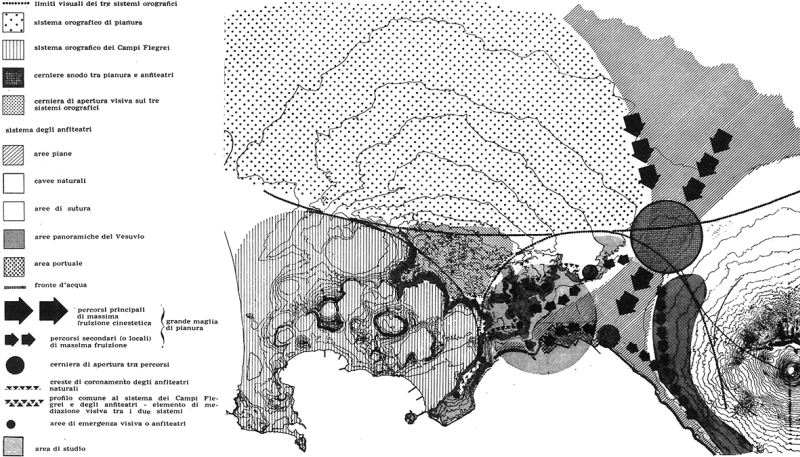

Fig.

2 - Salvatore Bisogni and Agostino Renna, Introduction to the Naples

urban design problems. Visual and kinaesthetic enjoyment fields of the

amphitheater system, 1963-64.

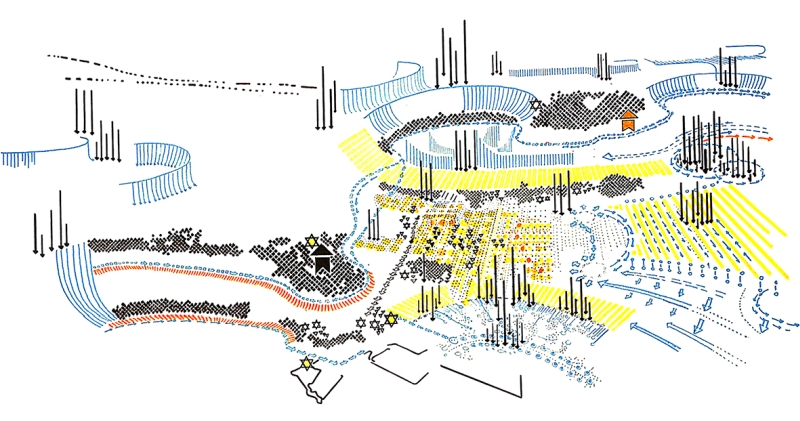

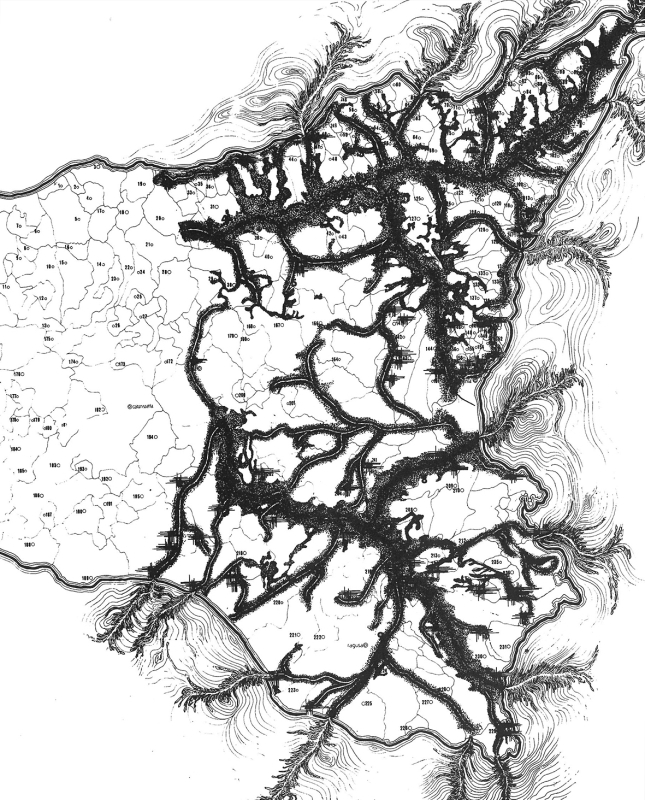

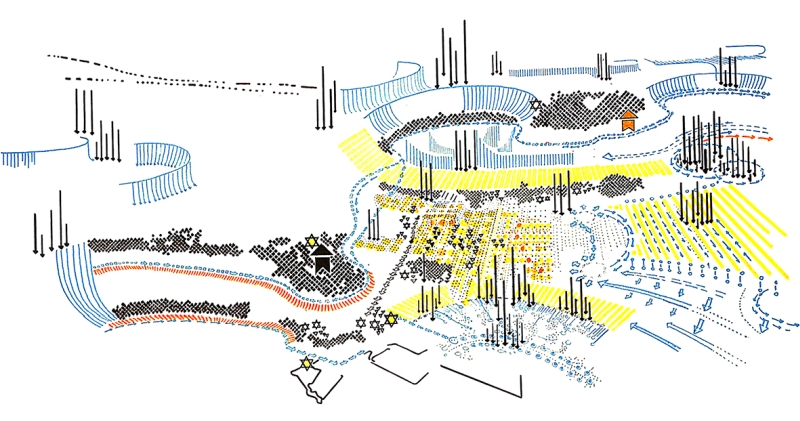

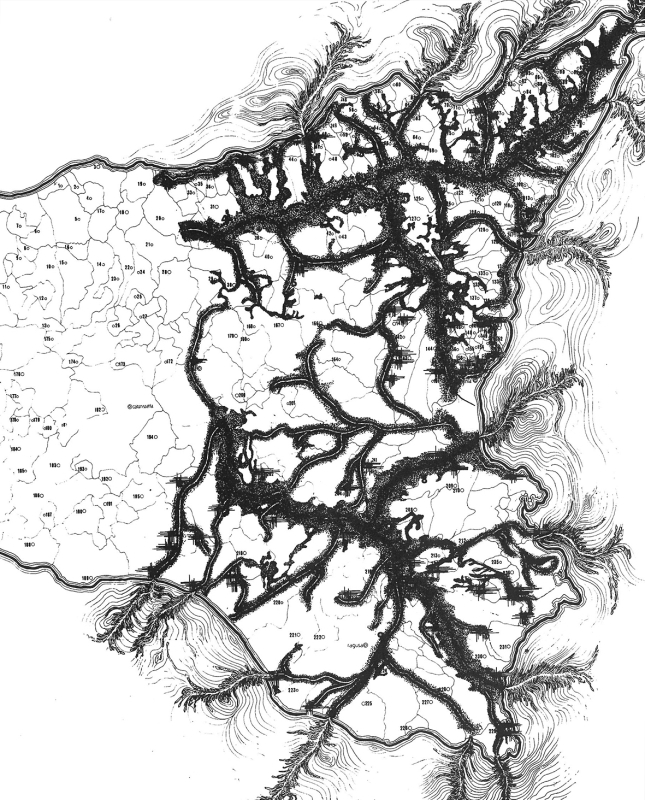

Fig.

3 - Salvatore Bisogni and Agostino Renna, Introduction to the Naples

urban design problems. Expressive model for emerging areas, lines and

fabrics, 1963-64.

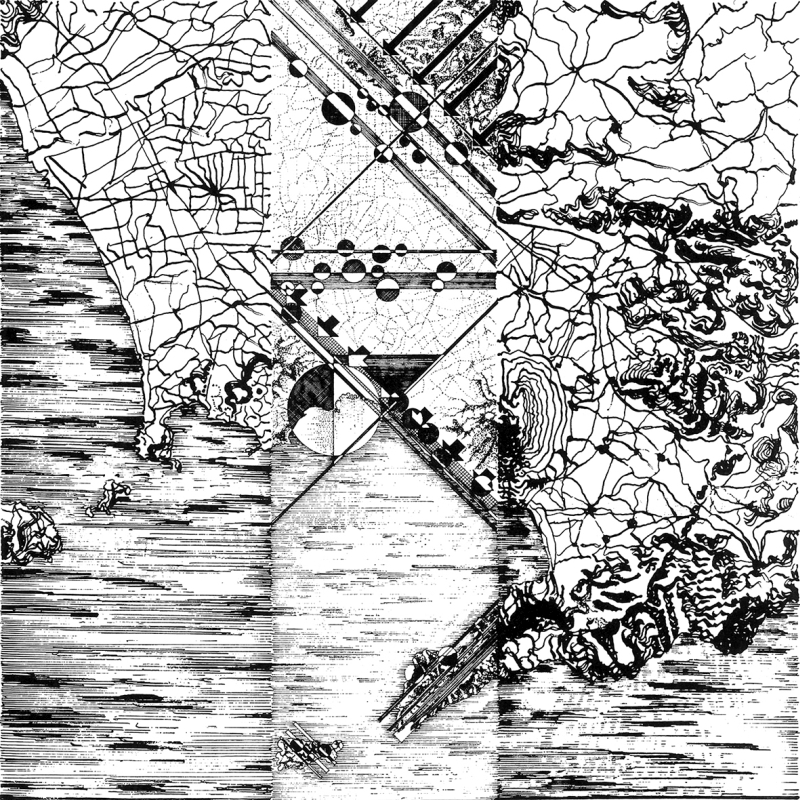

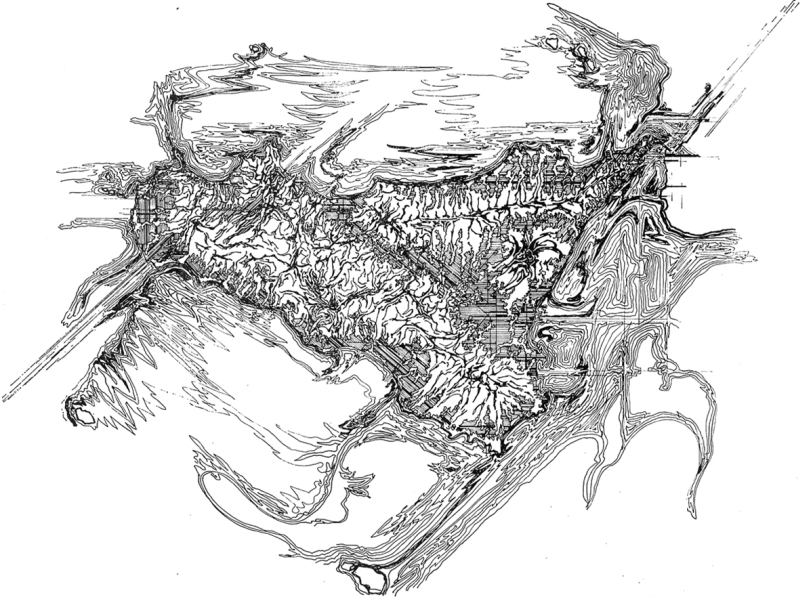

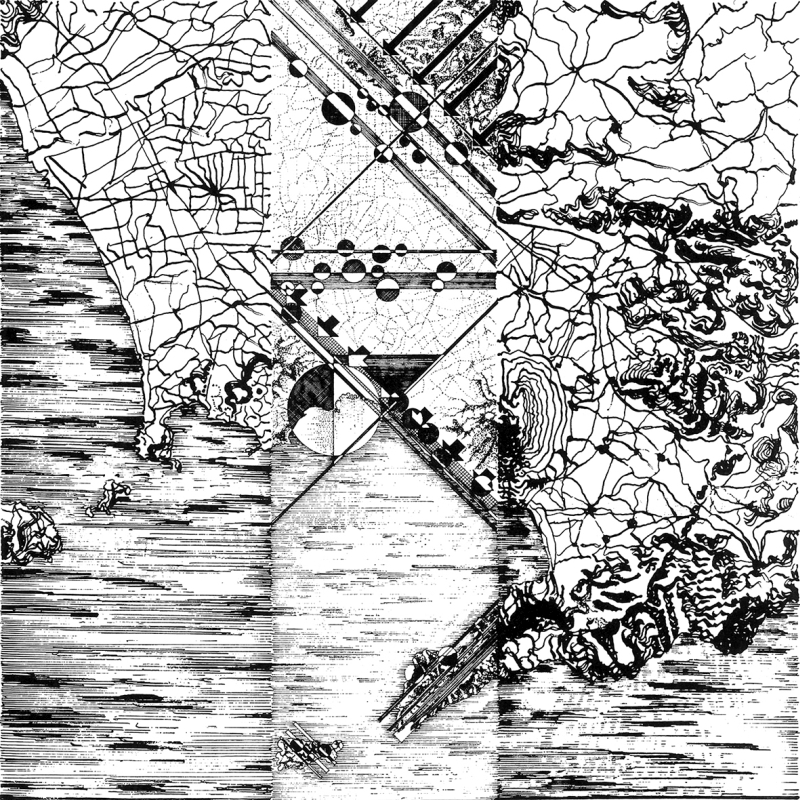

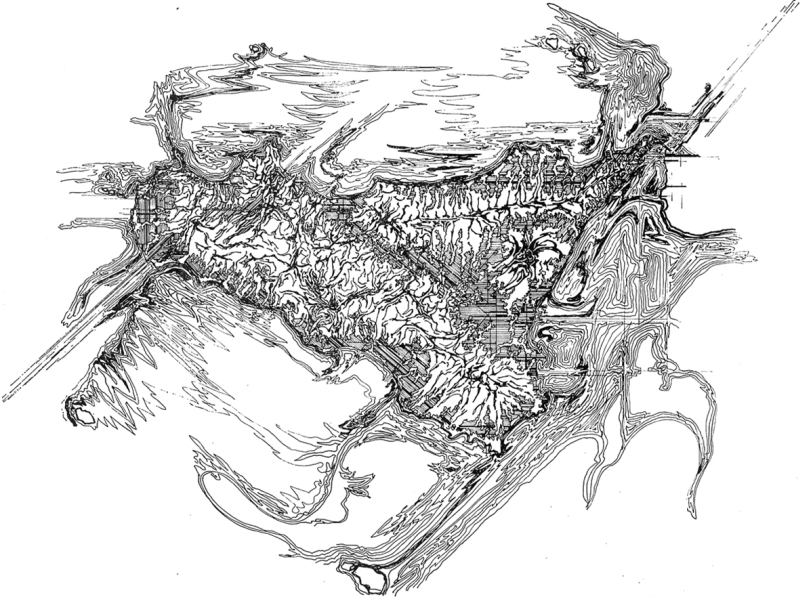

Fig.

4 - Carlo Doglio and Leonardo Urbani, Neapolitan area. Structure of

territory and liquefaction (liquidation?) of artifact, 1970.

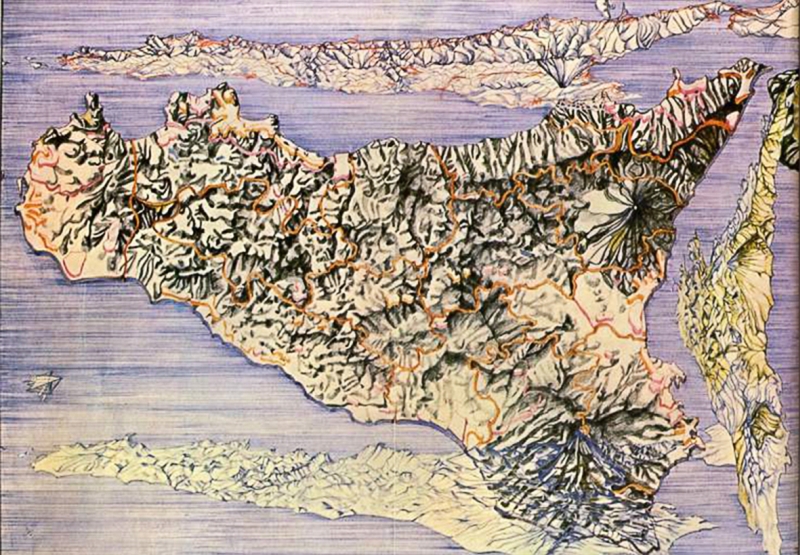

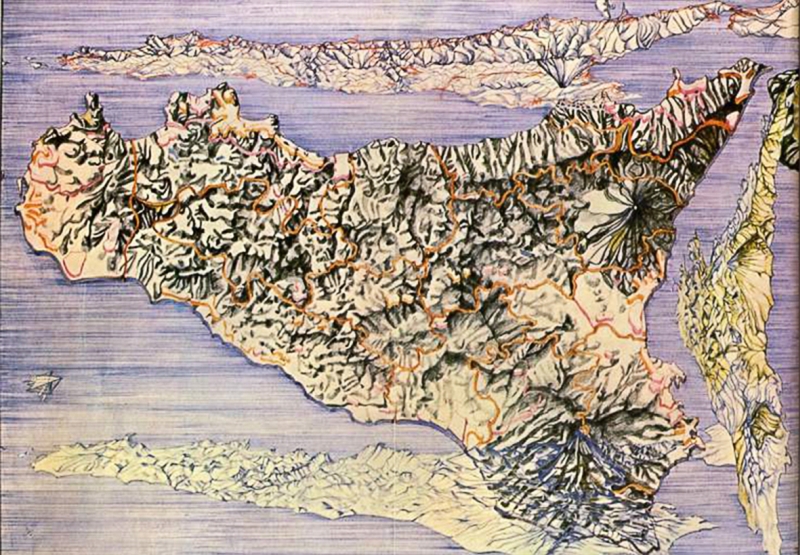

Fig.

5 - Carlo Doglio and Leonardo Urbani, La fionda sicula. Piano della

autonomia siciliana. Text and context: identification of formal

presences corresponding to Belice valley, central-southern belt,

Corleone and Palermo area, Etna, 1972.

Fig.

6 - Carlo Doglio and Leonardo Urbani, La fionda sicula. Piano della

autonomia siciliana. Polyducts and land use, 1972.

Fig.

7 - Michele Procida, Braccio di bosco e l'organigramma. Forest Arms,

1984.

Fig.

8 - Leonardo Urbani, Braccio di bosco e l'organigramma. The birth of

design, 1984.

Fig.

9 - Nicola Giuliano Leone, Braccio di bosco e l'organigramma. The three

Sicilies: Ionian, Tyrrhenian and of the African canal one, 1984.

Fig.

10 - Nicola Giuliano Leone, A “perspective” for the

Amiata

Project: preparatory drawing (general plan of the territory of Mount

Amiata's mountain community, Indian ink and pastel on glossy paper) and

perspective (final version, with names of urban centers and

boraciferous soffions, Indian ink on glossy paper), 1979-1981; Logo for

the Mount Amiata producer cooperatives, Indian ink on glossy paper,

1981.

The topic of drawing here addressed is related to the transition in

scale of the architectural design: on the capability and consistency of

Drawing in representing and communicating a spatial form and an idea of

space even to the big scale, territorial and geographical.

The development of territory representation

proceeds hand in hand with the succession and evolution of the visions

of territory

that change over time, which is why we want to initially propose the

events that over the course of the second half of the twentieth century

led to the most recent theories, as well as the related forms of design

writing.

Since the last century, the relationship between space and

time has

changed radically, both in terms of technological advancement that has

increased the speed and expansion of settlement and infrastructural

processes, and in terms of the increasing speed of travels and the

possibility to reach every part of the globe in ever shorter time. As

man’s radii of action and the extension of his interventions

change, the dynamics of mutation in the territory vary accordingly and

with them the scales of the project, which must confront broader

dimensions and new topics that no longer concern only the scale of the

city and its surrounding but the bigger scale of the territory in which

the former is included.

However, the combination and expansion of these accelerating

phenomena has made evident the inadequacy of the usual design tools and

the absence of big scale intervention techniques capable to control the

effects or provoking them. This opens at both practical and theoretical

levels to reflections that concern not only the research for an updated

design methodology, but also the need for an appropriate means of

expression to represent its intents.

The design in the territory

The design at the territorial scale was until the last six

decades

linked to the theme of the city; only after a series of events it did

assume its own thematic autonomy. It was in fact the onset of problems

related to conurbation and uncontrolled city expansion that gradually

shifted the plane of architectural debate beyond urban limits.

In 1930 the geographer Walter Christaller published his theory

on

central locations, in which the city was considered in an integrated

view as the physical pole of the surrounding territorial system. From

that moment, as Emilio Battisti states, the city is recognized as

structurally connected to its territorial surroundings; a connection

from which it will no longer be «conceptually admissible to

speak

of the city in isolation from the territory» (1975, p. 224).

It was evident that something was changing: new and relevant

topics

required the widening of the viewpoint towards broader dimensions and

new criticalities heralded the need for renewed tools to push beyond

the design and functioning of the forma urbis.

The apparent unresolved disagreement between city and countryside[1]

on the one hand, the problems related to the dislocation relations

between production-service-residence places on the other, and finally

the changing physiognomy of the city into a metropolis, or megalopolis,

which, was advancing unchecked engulfing the surrounding land in

disorderly fashion, gave an account of an indisputable truth: in order

to defuse some of the effects produced by modern urban planning

practices, it was not enough to have recourse to predictive logic and

zoning, but it was necessary to question of new spatial figures capable

to find answers to the emerging problems[2].

Such was the premises of the 1962 Stresa Conference in which city-territory

was the central theme, a new dimensional entity that was now to be

based on the decentralization of the city’s load-bearing

functions and their more extensive and homogeneous re-location.

«What is the fundamental dimension to be referred to in our

urbanistic development hypotheses? What, too, is the structure that

frames our formal research?» (1962, p. 16). These are the

fundamental questions that Giorgio Piccinato, Vieri Quilici and

Manfredo Tafuri ask about the current situation: that is, does the term

of city-territory indicate only a change in scale

or also a different visual angle in dealing with the rapid changes that

were taking place?

The design of territory

Parallel to the hypotheses for countering peripheralization

and

urban sprawl that still identify the system-city as the sole focus to

be resolved, a different point of view is asserted extending the

concepts of space and architectural form to the entire territorial

context. The urbanocentric conception is abandoned in favor of a vision

that recognizes the structure and materiality of the entire territory,

as a concrete space operable through the tool of the project design: a

morphological context of which the city represents only one of the

elements contained therein, on par with the natural facts and the other

anthropic signs; as well as an autonomous system and an exhaustible

resource, to be understood, re-signified and protected through

architectural operations. Similarly, territory represents the result of

the layering of successive actions. And this means not only more or

less modified physical environment, but also behavioral attitudes to it

refered (Olivieri 1978, p. 14).

«Territory is not a data, but the result of several

processes», André Corboz writes about it.

«In other

words – he continues –, territory is object of

construction. It is a kind of artifact. And since that it also

constitutes a product. [...] Consequently,

territory is a project. [...] These different

translations of territory into figures refer to an indisputable

reality: that territory has a form. Indeed, that

it is a form. Which, of course, doesn’t

necessarily have to be geometric» (1985, pp. 23-24).

In light of the current conditions, the territorial topic is

now

more central than ever since new and different complexities related to

the advance of a conflict involving both marginal and extended

territories are added to the previous ones, in which forms, practices

and cultures acting through complex relationships and ancient balances

are dying out (Falzetti 2015, pp. 10-11). Reasoning about the

capabilities of architectural design as a tool able to producing

visions and about the process of form’s

construction,

which has no dimensions but rules and principles, thus becomes

necessary to analyze and understand the phenomena of the world and to

be able to intervene in his processes of transformation that affect all

scales of the artifact: from the building, to the city, to the

territory.

The drawing of territory

The term construction indicates to the

territorial and

geographical dimension a practice that is not exclusively about

building, but about the meaning and value of a process of

reinterpretation and formal restructuring of the existing. In the

architectural design on the grand scale, which contributes to the

construction of a formal whole, not only the dimensions but also the

composition of space change, determined by the spatial relationships

between distinct, even distant, elements. In relation to the space

to be represented, therefore, the type of representation

of space

changes, which must describe not only different scales but also the

elements and relationships that define it, as well as communicate, even

at this scale, a spatial form and idea of space. Canonical drawings

such as plans, sections and elevations, often referring to artifacts of

the smallest dimensions, are thus replaced by planimetric and

perspective views suitable for reproducing the field under examination

in its entirety. Similarly the urbanistic illustrations give way to the

invention of an almost biographical writing aimed to describe

intentions and interpretations through the use of an expressive code

«that stands halfway between concept and image»

(Pellegrini

1966, p. 103)[3].

A very important date for the historical and thematic

development of

the topic is that of 1963-64, the year of Salvatore Bisogni and

Agostino Renna’s graduation thesis precisely titled Introduction

to the Naples urban design problems[4].

It is no coincidence that this turning point occurs just in Naples, an

area in which natural facts, first and foremost that of Vesuvius, which

has always been a physical and symbolic landmark of the Parthenopean

environment, impose themselves with considerable formal and evocative

impact.

The study questions the big scale morphological problems in

the face

of the research for a design methodology that seeks to overcome the

operational impasse, which is why a non-descriptive but more

specifically design point of view is applied. Initially, the authors

perform a decomposition of the field by analyzing the present features

in isolation, to finally propose an urban model without hierarchy of

levels, in which orographic structure and building fabric, natural

pre-existences and anthropic layout, constitute a formal and

inseparable continuity: a complex «[...]

“Design” not

to be understood as a visually well-ordered whole, but as a “field”

of formal relationships between the constituent elements»

(Bisogni and Renna 1966, p. 131).

The term Design here takes indeed on the

double meaning of

tool and composition; it is both a means of representation and the

object of representation itself. This is important to grasp that the

theme of Bisogni and Renna’s work is twofold, as it

investigates

in its entirety the design question of big scale but also the problems

related to its representation. «The set of their drawings,

suspended in a productive ambiguity between symbolic image and

objective projection, is [...] capable to depict all the material,

geographical, typological and historical complexity of an urban and

territorial whole», Vittorio Gregotti in fact writes (1974,

p.

7). Bisogni and Renna state that they initially operated in the usual

way, using planimetric drawings to represent the organizations of the

area; then, through diagrams and bird’s-eye views (Figs. 1,

2),

«it appears the attempt to substitute for realistic

type direct annotations some symbols tending to represent relations

between forms rather than forms»

(1966, p. 129). The representation of territory until then limited to

an urbanistic vision is definitively overcome by a drawing capable to

illustrate in an autographic and interpretative way what has been

analyzed but also what has been inferred and proposed: the images of

concrete forms are transported to the plane of symbolism and formal

evocation, highlighting the formal relations among them through the

preparation of expressive models (Fig. 3),

synthetic and

evocative elaborations in which suggestions and one’s own

interpretations are also translated into drawing.

Several design researches began in those years, now focusing

on the

form and structure of the territory. Carlo Doglio and Leonardo Urbani

constitute two particularly relevant figures and, for academic reasons,

also in some ways two bridges between Naples and Palermo regarding the

applied methodology. At the base of their design theories are inferred

a certain degree of abstraction that unties the

form-structure dynamic of the territory to the system that identifies

it in a given period, and the use of an expressive language capable of

offering cultural interpretations of the territory (Doglio and Urbani

1970, p. 35). These assumptions are perfectly matched by the visions

the two architects propose for Naples (Fig. 4) but above all for

Sicily. Specifically, the drawings in support of La fionda

Sicula. Piano della autonomia siciliana[5] (Figs. 5, 6) and Braccio

di bosco e l’organigramma[6]

(Figs. 7, 8, 9) fully demonstrate the complexity to illustrate a

discourse that holds together the natural and the intangible data,

whether economic or administrative. And it’s precisely the

research for a mathematically impossible sum between

different elements

that leads to a form of drawing that must at certain times necessarily

abandon objectivity in order to succeed in communicating an idea. The

result is drawings that partly depict the structure of the territory

through the analysis of orography, and partly drawings (of considerable

aesthetic content both for creative invention and technical execution)

to whose formal interpretation is entrusted the sense of design

intention.

One of the main draughtsmen of Doglio and Urbani’s

works was

Nicola Giuliano Leone, architect and urban planner, author of several

projects and town and territorial plans in Italy and abroad. His

representations constitute the distinctive feature of his projects,

true «endo-products capable to communicate immediately the

idea

of city and territory in a virtuous symbiosis of sign and

thought» (Gabellini 2020, p. 10). This is patient and

meticulous

work for which digital means of representation can hardly replace the

communicative power of a hand stroke with great artistic and expressive

value. One experience in particular sums up the importance of drawing

as a research tool in Leone’s work. In 1979 he was

commissioned

to curate a perspective that would serve as an icon for the tourist

launch of Mount Amiata and to construct a trademark for the production

of pork sausages started on the same mountain (Fig. 10). Drawing, taken

as a figurative medium through which to understand, to rationalize and

to shape the existing, here also becomes a tool to strengthen the

social cohesion of a physically unitary territory but divided into

eleven municipal administrations and two provinces. Like Vesuvius for

the Parthenopean capital, Etna for eastern Sicily and beyond, the

figurative constructions of Hokusai’s Mount Fujiyama and

Cézanne’s Sainte-Victoire Mountain, Mount Amiata

is

elected as a territorial and landscape reference for the construction

of an idea of territory, in which the physical element artificially

acquires social significance becoming a cultural icon.

«To represent the territory is already to take

possession of

it – Corboz writes indeed –. Now, this

representation is

not a cast, but a construction. One makes a map first to know, then to

act» (Corboz 1985, p. 25).

Through drawing, territory is broken down into forms that

attempt to

be known through its graphic geometrization. Similarly, in order to

design it will be necessary to intervene by recomposing the matter of

which it is made up, that is forms assembled in space. However, simple

orthogonal projections fail to exhibit the physical, anthropological

and immaterial complexities present in the territory. Thus we move on

to a less objectifying form of writing, sometimes pictorial, but able

to interprete the spatial phenomena of territory, cultural and formal

ones, as well as communicating through one and the same sign an idea of

design. Architecture Drawing, even at the territorial scale, therefore

constitutes an inextricable part of all its phases. In addition to

being a tool for analysis and representation, it is also entrusted with

the expressive channel: cooperating with the formal aspects, it is in

fact able to emphasize theme and accents; and through the use of a

specific stylistic code it allows us to understand, along with the

work, built or merely imagined, the author as well.

Notes

[1]

In this regard, Giuseppe Samonà proposes in 1976 his theory

about The city in extension,

whose ever actual key to understanding lies on the possible

«very

lively dialectic between the balances of the new spatial relations that

will be created between the agricultural territory that has become a

city in extension and the big natural territory that is not permanently

inhabited».

In: Samonà G. (1976) – La

città in estensione.

Atti della conferenza tenuta presso la Facoltà di

Architettura

di Palermo il 25 maggio 1976, STASS Stampatori Tipolitografi Associati,

Palermo.

[2]

In this same period were the spatial and figurative researches of

Ludovico Quaroni, the experiments on the theme of the unicum

of business centres or territorial parks, or even those on the continuous

city

somehow already introduced at the turn of the 1930s by Le Corbusier who

coins the term of geo-architectures: city plans that are developed on

the grand scale proposing in the same sign a housing system and a model

of mobility.

[3]

Cesare Pellegrini’s design proposals published in 1966 in La

Forma del Territorio of «Edilizia

Moderna» No. 87-88, a sort of compositional exercises defined

by the same author with the terms of figurative qualifying

interventions,

demonstrate in this sense an employment of drawing not as a tool of

representation but as a means of composing. Pellegrini works with the

precise intention to reorganize the structure (to restructure

precisely) of a part of territory through the insertion of signs, often

abstract and of uncertain entity but charged with formal

intention, that introduce image potential into the

surrounding.

[4]

The work related to the

dissertation (Supervisors: Profs. Giulio De Luca and Francesco

Campagna) was initially published in 1966 in the monographic issue

edited by Vittorio Gregotti La Forma del Territorio

of «Edilizia Moderna» No. 87-88 and later, in 1974,

in the volume Il disegno della città di Napoli by

the same authors Salvatore Bisogni and Agostino Renna with an

introduction by Gregotti.

[5]

The project of La fionda sicula

is first and foremost about the vision of a Sicily as a central point

and bridge of exchange within the Mediterranean, proposing a new

framework of territorial infrastructures (the polyducts)

to make crossing and internal transportation easy; then also a Plan

for the autonomy

of a region that is careful of own resources, which focuses on its

territorial talents to undertake production activities and a new

economic development. In: Doglio C. and Urbani L. (1972) – La

fionda sicula. Piano della autonomia siciliana. Il Mulino,

Bologna.

[6]

In Braccio di bosco e l’organigramma,

the two architects present a possible model for the administrative and

productive development of the region, in which natural geometries and

ideal geometries overlap generating a new territorial design governed

by a dual-regulatory approach. In the Forest

Arms, natural vocations prevail: these depart

from the island’s historical-natural lines of force,

constructing a territorial fabric for which a strict

constraint regulation are provided, aimed to safeguard and

to preserve its original characters. For the remaining areas, in which

instead territorial indifference prevails,

regulations will be with agile constraint,

that is, from time to time directed to the emerging needs of individual

productive districts and their enhancement. In: Doglio C. and Urbani L.

(1984) – Braccio di bosco e

l’organigramma. Flaccovio Editore, Palermo.

References

BATTISTI E. (1975) – Struttura urbana e

trasformazioni territoriali. In: V. Gregotti (edited by), Architettura

e urbanistica. Forma-spazio habitat. Fabbri, Milan.

BISOGNI S. and RENNA A. (1966) –

“Introduzione ai

problemi di disegno urbano dell’area napoletana”.

Edilizia

Moderna. La forma del territorio, 87-88.

CORBOZ A. (1985) – “Il territorio come

palinsesto”. Casabella, 516 (September).

DOGLIO C. and URBANI L. (1970) – “Da

Napoli e Palermo”. Parametro, 2 (July-August).

DOGLIO C. and URBANI L. (1972) – La

fionda sicula. Piano della autonomia siciliana. Il Mulino,

Bologna.

DOGLIO C. and URBANI L. (1984) – Braccio

di bosco e l’organigramma. Flaccovio Editore,

Palermo.

FALZETTI A. (2015) – “I limiti della

ricerca nel progetto della continuità”. In: Id.

(edited by), La città in estensione.

Gangemi Editore, Rome.

GABELLINI P. (2020) – Un disegno a

più dimensioni. In: N. G. Leone, Il

progetto urbanistico. Planum Publisher, Rome-Milan.

GREGOTTI V. (1974) – Introduzione.

In: Bisogni S. and Renna A., Il disegno della

città Napoli, Cooperativa editrice di economia e

commercio, Naples.

GREGOTTI V. (1987) – Il territorio

dell’architettura. Feltrinelli, Milan.

MURATORI S. (1967) – Civiltà e

territorio. Centro Studi di Storia Urbanistica, Rome.

OLIVIERI M. (1978) – Come leggere il

territorio. La nuova Italia, Florence.

PELLEGRINI C. (1966) – “Note per

un’architettura

del paesaggio: mitologia e specializzazione”. Edilizia

Moderna.

La forma del territorio, 87-88.

PICCINATO G., QUILICI V. and TAFURI M. (1962) –

“La

città territorio. Verso una nuova dimensione”.

Casabella-Continuità, 270 (December).