Minimum drawing, maximum dwelling.

Existenzminimum forms between drawing and design

Giovanna Ramaccini

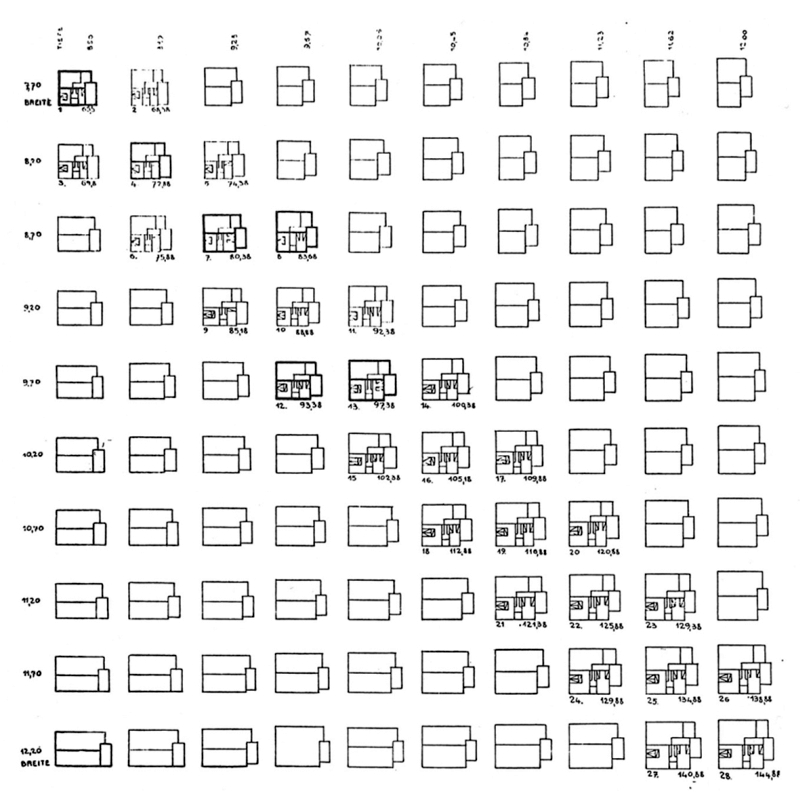

Fig.

1 - Alexander Klein, Comparison and evaluation of different projects

reduced to the same scale (Baffa Rivolta, Rossari 1975, p. 90).

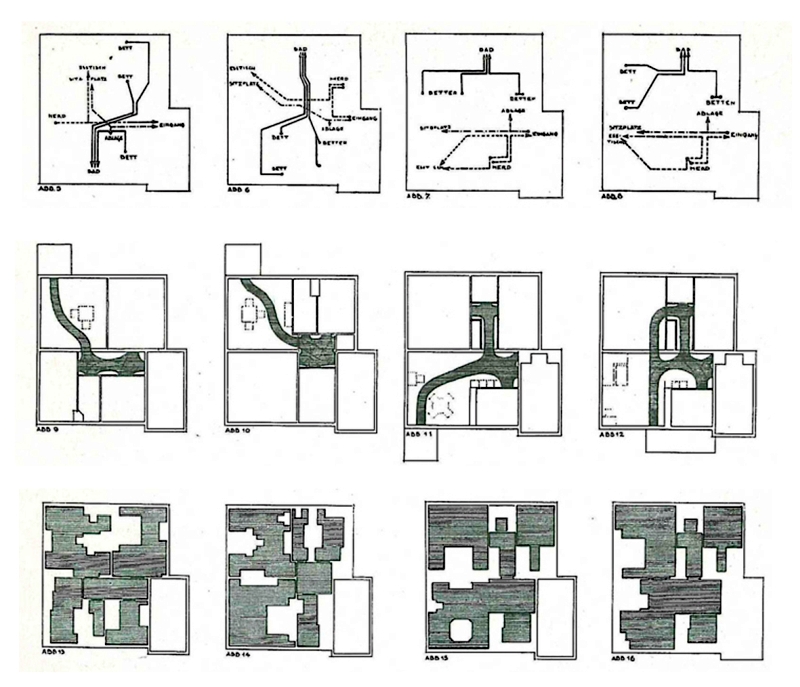

Fig.

2 - Alexander Klein, Analysis of paths and free surfaces (Baffa

Rivolta, Rossari 1975, p. 94).

Fig.

3 - Alexander Klein, Analysis of internal elevations (Baffa Rivolta,

Rossari 1975, p. 98).

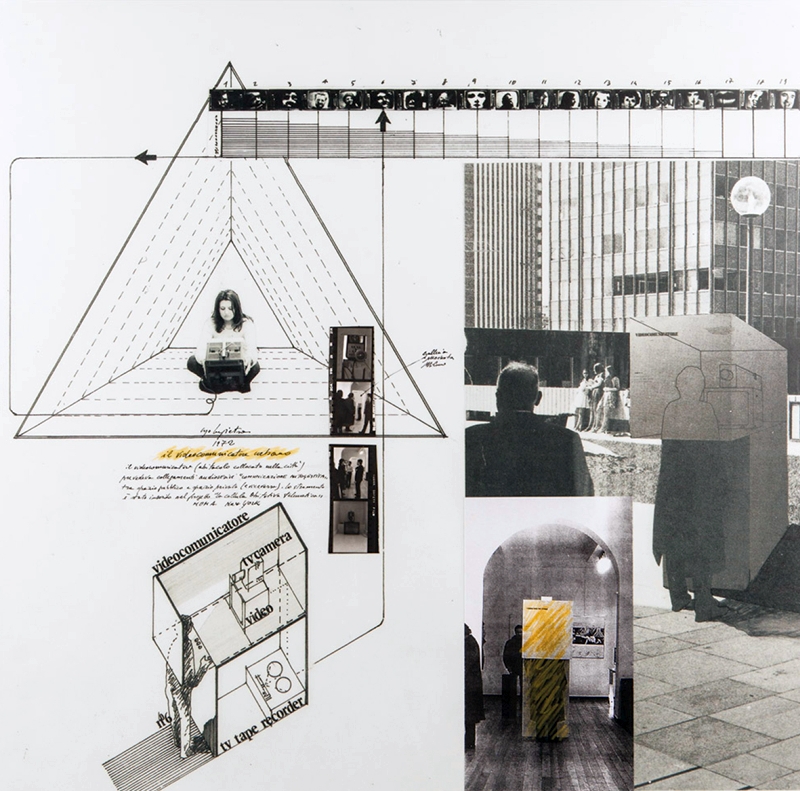

Fig.

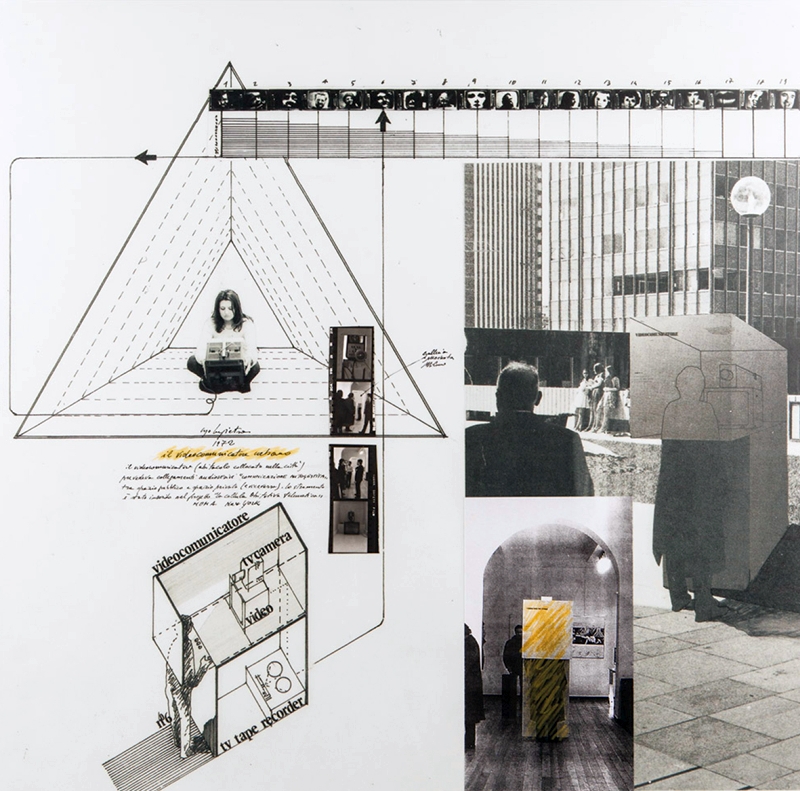

4 - Ugo La Pietra, «Casa telematica», 1975.

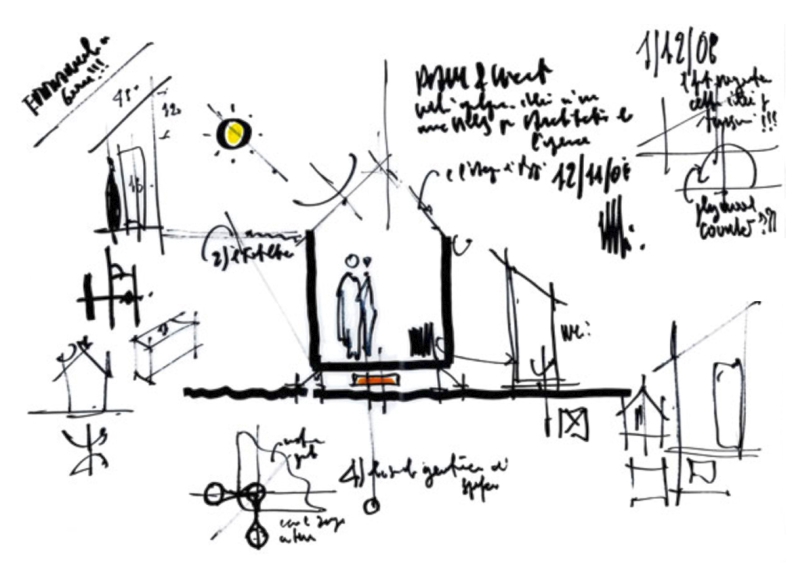

Fig.

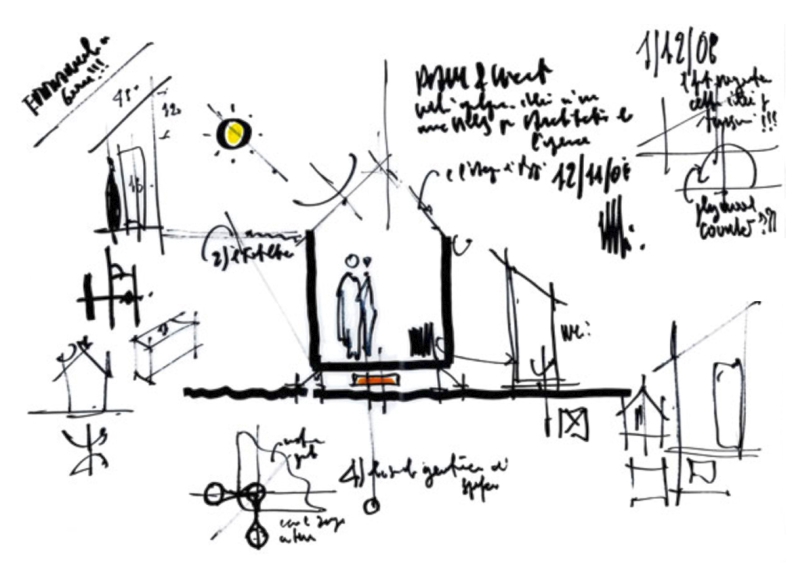

5 - RPBW, «Diogene», 2008.

Fig.

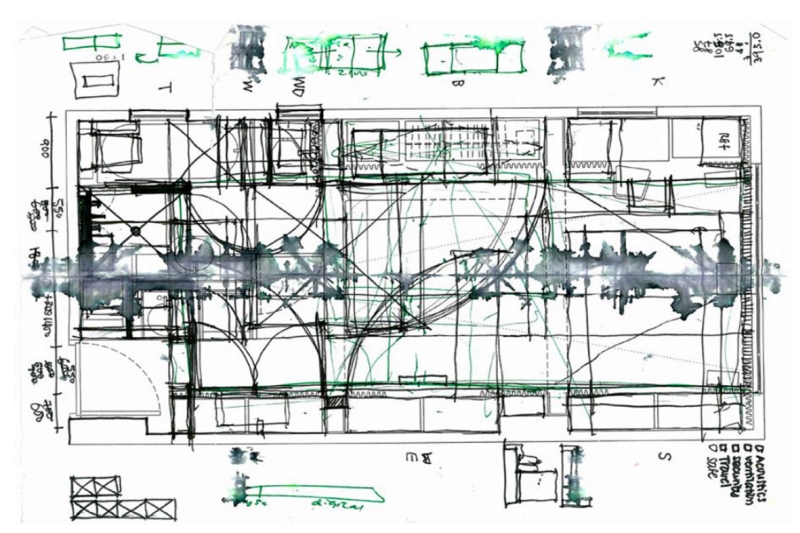

6 - Gary Chang, «32 m2 Apartment», studi di

progetto.

Fig.

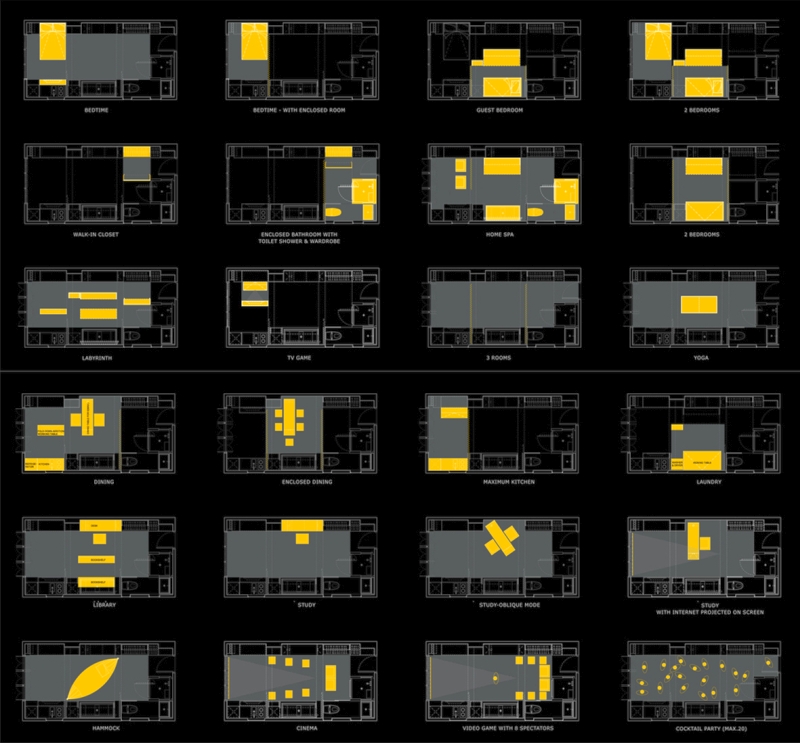

7 - Gary Chang, «32 m2 Apartment», design studies.

Fig.

8 - Gary Chang, «32 m2 Apartment», project.

Introduction

«Aldo Rossi had a totally different way of dealing

with

technicians from what we had experienced up until then: he made

sketches, then presented them and waited for the technicians to make

all the observations and corrections [...] so much so that one day my

uncle said to him, in his gruff way: ‘But architect,

can’t

you bring us executive drawings instead of these sketches from which

you can’t understand anything?’ That was the only

time I

saw Rossi angry» (Alessi 2016, p. 76). The anecdote, which

concerns the stormy incipit of what would later turn out to be the

successful partnership between Aldo Rossi and the design company

Alessi, exemplifies the need to adopt a codified language when

communicating an idea, even when the interlocutor concerned is a

notorious expert. The difficulty of the transition from the immediacy

of the conceptual drawing to the accuracy of the working drawing is

particularly evident in cases where the execution of the project

involves the definition of standards, possibly to be reproduced in

series. In this regard, with specific reference to the architectural

project, the theme of existenzminimum takes on

particular

importance, where the dwelling, understood as the favoured place to

guarantee high quality standards and to respond to the needs of its

inhabitants, is conceived as a machine à habiter

in

which the reduced dimensions of the spaces are combined with high

functionality characteristics. At the international level, the concept

of existenzminimum was sanctioned by the II

Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne

–CIAM – held between 24 and 27 October 1929 in

Frankfurt am Main (Die wohnung fur das existenzminimum 1979).

The congress, curated by Ernst May together with Mart Stam, sees some

of the main protagonists of modern European architecture take part in

the theoretical debate, aimed at defining a minimum housing standard

for the urban population.

Professor Dr. Water Gropius from Berlin was entrusted with the

general summary «The Sociological Assumptions of Minimum

Housing». Victor Bourgeois from Brussels and Pierre Jeanneret

from Paris dealt in detail with the issue of housing for the minimum

standard of living. Bourgeois started with the physical fundamentals

and Pierre Jeanneret – replacing Le Corbusier who was in

America

– mainly indicated the possibilities of realisation. Finally,

Hans Schmidt, from Basel, gave a talk on the important topic

«Minimum Housing and Building Regulations» in which

he

showed how the current building regulations, with their rigid

characteristics, do not at all prevent an effective housing solution

for the minimum standard of living. (Aymonino 1976, p. 96).

Starting from the principles illustrated by Ernst May in his

introductory contribution, the minimum housing standard is interpreted

in both quantitative and qualitative terms, taking into account the

biological and sociological conditions aimed at satisfying the material

and spiritual needs of the inhabitants, with specific reference to mass

housing (Aymonino 1976, p. 100). Within the different types of houses

studied in the 1920s, the one intended for the working class was the

one most investigated by architects, as it allowed them to express more

strongly the ideas of rationality applied to interiors, such as order,

simplicity and economy. (Savorra 2019). In addition to the theoretical

contributions, the CIAM exhibition Die Wohnun für

das Existenzminimum,

co-ordinated by May himself, at which numerous examples of minimal

houses were exhibited and subsequently published, is equally important.

It is a series of floor plan images of flats located in different parts

of the world, which, as intentionally expressed by the participants in

the debate, is motivated by the intention to codify the different

equipment sizes by introducing an international convention, according

to the criteria of industrialisation and Taylorisation – as

described by Le Corbusier and Pierre Janneret (Aymonino 1976, pp.

113-123) – and hoping to achieve typological standardisation.

After all, the concept of type is insistently sought after with the

housing experiments by the Modern Movement: «from the

prefabricated town planning of the Bauhaus […] to the

numerous

experiences related to the construction of Siedlungen»

(Belloni 2014, p. 33). For the specific purposes of this contribution,

one thinks in particular of the studies and experiments by Alexander

Klein and the importance they assumed for the development of existenzminimum

theory.

Minimum drawing, maximum dwelling[1]

With regard to the specific aims of this contribution, in this

part

of the text, it is important to stress the value of drawing in research

dedicated to existenzminimum, highlighting its

implications

from the design point of view, starting with the studies conducted by

Alexander Klein since 1906 (Baffa Rivolta, Rossari 1975).

Klein’s

aim was to provide tools for measuring and verifying optimal

performance in terms of the organisation of living space in order to

develop a minimum living standard. He developed a comparative method,

which can be implemented entirely within the drawing process, because

it is based on the comparison of diagrammatic plans that are

graphically uniform, thus proposing a taxonomic classification that has

its roots in 19th century treatises, in which the transmission of

knowledge is functional to its practical application – one

thinks

of the tables in the Précis in which,

identifying Convenance and Économie

as the two fundamental criteria for design practice, Durand proposes a

veritable «reasoned handbook of architectural prototypes that

are

easy to use in relation to functional needs» (Belloni 2014,

p.

30) –, and which will be adopted by subsequent design manuals

(Strappa 1995, p. 110) – from the Manuale

dell’architetto by Mario Ridolfi (1946) to the Architettura

pratica by Pasquale Carbonara (1954).

The functionalist experience, which finds in Klein one of its

greatest exponents, works on the «fine-tuning of part-types

of

building organisms (staircase, office, bathroom-kitchen, room,

classroom, etc.) that [can] once again become instruments of a broader

architectural composition» (Aymonino, Aldegheri, Sabini 1985,

p.

11). The accommodation is designed on the basis of the identification

of three main moments of daily activity in the domestic environment:

cooking-eating, living-resting, and washing-sleeping, connected by

short, mutually non-interfering steps. The survey method developed by

Klein is divided into three stages: proceeding from statistical

analysis by means of questionnaires, through the reduction of projects

to the same scale, to the graphical method by which «to

refine a

project meaning to increase the efficiency of the dwelling while

maintaining the same surface area or to decrease the surface area while

maintaining the efficiency of the dwelling» (Baffa Rivolta,

Rossari 1975, p. 93). Although clearly oriented towards identifying the

functional and distributive characteristics of buildings,

Klein’s

classification cannot be understood as a mere objective method of

evaluating living space. Despite being schematic representations, the

mediation value they assume between theoretical elaboration and design

realisation is by now well established «[combining] an

extraordinary capacity for descriptive synthesis with a great potential

for poetic-ideative projection, at the same time establishing the

possibility of an authentic scientific dialogue between the words of

theory and the things of construction» (Ugo 1986, p. 23).

While

the graphical method acts as an analytical tool, it also takes on an

operational role in the creative process where, by comparison, it

attributes a genetic and inventive component to the schematic plan (Ugo

1986, p. 27; Purini 2000, pp. 155-156; Belloni 2014, pp. XXIII-XXV). On

the other hand, this is consistent with the context of modern thinking

that gives the plan a central value in design at different scales, from

architecture to the city, and even involving social issues (Carones

2017, pp. 37-59). Just think of Le Corbusier’s exclamation:

«The plant is the generating element. So much the worse for

the

unimaginative!» (1973/2010, p. 35). Against the scientific

definition of the standard, Klein introduces a psychological lens.

We are all aware of the harmful influence of tobacco, alcohol,

spices, etc., and we take an interest in these problems; however, only

a few of us take an interest in the scientifically proven fact that a

favourable environment can have a healthy effect on our mental

condition [...]. The accommodation we build for ourselves must be

actively and organically related to the living conditions and cultural

needs of our time, and it must also meet the necessary demands for

greater economy and simplicity; in a word, it must help us in every

part and in every respect to make life easier for ourselves while

maintaining our physical and spiritual energy. (Baffa Rivolta, Rossari

1975, p. 77)

Besides clear distribution criteria, in fact, the adoption of

simple

forms in construction, layout and furnishing are considered fundamental

to guaranteeing calm, rest and recuperation of the energy consumed

during work. From this perspective, it is interesting to note how the

attention paid to the intimate dimension of living is confirmed in

representations exclusively aimed at interior spaces. The plan diagrams

of the dwellings are associated with their interior elevations in order

to assess the spatial quality perceived by the inhabitants. Thus,

window surfaces – sources of light and ventilation

– the

arrangement of furniture along the walls, shaded areas as well as free

surfaces are shown. So, in order to guarantee as free circulation

spaces as possible and to avoid «a useless waste of physical

strength, generated by the continuous need to accelerate and slow down

one’s pace and repeatedly rotate the body» (p. 95),

the new

dwelling calls for the need for storage units built into the walls

rather than bulky furniture set against the walls, leading to the

integration of furniture into the architectural space and thus to a

standardisation of furnishings based on the criteria of modularity,

versatility and componibility (Forino 2019, pp. 193-195; Nys 2020). As

perceived by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeannert in the design of the casiers

standard of 1924 or by Adolf Loos in his writing

programmatically titled The abolition of furniture,

also dated 1924, where the author emphasises the future dissolution of

mobile furniture because it is expected to be absorbed by the wall.

The walls of a house belong to the architect. There he rules

at

will. As with the walls so with any furniture that is not moveable,

such as built-in cupboards and so forth. They are part of the wall, and

do not lead the independent life of ostentatious unmodern cabinets.

(Loos 1972/2014, p. 324)

Moving on to introduce the evolution of the existenzminimum

in the contemporary era (Irace 2008), it is exactly from the reference

to the element of the wall, by definition the boundary between interior

and exterior space, that it seems necessary to focus on an aspect that

has only been treated implicitly so far. Although associated with an

increase in the level of equipment and performance, the reduction of

surfaces in living space entails an articulated and complex conception

of housing, which inevitably takes into account a relationship with the

outside world (Baffa Rivolta, Rossari 1975, pp. 36-37), both from a

functional and an emotional point of view. One thinks of Ugo La

Pietra’s far-sighted Telematic House (1972), conceived as a

micro-architecture with a triangular cross-section, in which

communication with the outside world takes place through virtual

connections mediated by equipment such as the

“Ciceronelettronico” and the

“Videocomunicatore”. Or think of the more recent

Diogene

project, by RPBW (2011-2013), conceived as a perfect machine

à habiter,

standardised and in the forefront of technology, in which the

relationship with the outside world is ensured by a vertical cut, of

humanistic memory, “in contact” with the sky

(Ottolini

2010, pp. 17-31).

Conclusions

Turning to the conclusions, it is only right to dwell on how

the

advent of the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to live in

adaptable and flexible homes, whose interiors can be modified and

reconfigured easily and with light intervention (Bassanelli 2020;

Molinari 2020). A need even more exasperated in conditions of minimal

living space. Although it preceded the emergence of the health

emergency, the experience of the Japanese architect Gary Chang is

exemplary in this respect (Chang 2012). Over a period of thirty years,

from 1976 to 2006, the designer transformed the 32 square metres of his

home into twenty-four different distribution solutions, each time

varying in response to changing personal conditions, conceiving

architecture as a device capable of adapting to change. If, on the one

hand, the idea is represented through plan sketches in which

annotations and afterthoughts are stratified, certainly functional to

the development of thought and probably sufficient for the relative

communication – given the specific coincidence between

designer

and client – on the other hand, the author develops plan

diagrams, addressed to an external public, entrusting the drawing with

a gesture of registration and documentation aimed at bearing witness to

a situation that is planned but changeable, because it is in continuous

evolution. Once again, as in the case of Klein’s diagrammatic

representations, the abacus of plants drawn up by Chang is not an

abstract scheme, but rather the instrument for the slow and progressive

definition of minimal forms, maximally adapted to life.

Notes

[1]

The title of the paragraph, as well as that of the entire article, is

intentionally referred to Karel Teige’s work The

minimum dwelling

(1932/2002). Although the text differs in its treatment from the topics

of the present contribution, it is an indispensable reference for the

literature relating to the reflection on the subject of minimum housing

that affects the international debate of the early 20th century.

References

ALESSI A. (2016) – La fabbrica dei sogni.

Alessi dal 1921. Rizzoli, Milan.

AYMONINO C. (edited by) (1976) – L’abitazione

razionale. Marsilio, Padova.

AYMONINO C., ALDEGHERI C., SABINI M. (1985) – Per

un’idea di città la ricerca del Gruppo

architettura a Venezia (1968-1974). Cluva, Venice.

BAFFA RIVOLTA M., ROSSARI A. (edited by) (1975) – Alexander

Klein. Lo studio delle piante e la progettazione degli spazi negli

alloggi minimi. Scritti e progetti dal 1906 al 1957.

Gabriele Mazzotta, Milan.

BASSANELLI M. (a cura di) (2020) – Covid-Home.

Luoghi e modi dell’abitare, dalla pandemia in poi.

LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

BELLONI F. (2014) – Ora questo tipo

è perduto. Tipo architettura città.

Accademia University Press, Torino.

IRACE F. (edited by) (2008) – Casa per

tutti. Abitare la città globale. Triennale

Electa, Milano.

CHANG G. (2012) – My 32 m2 apartment. A

30-year transformation. MCCM creations, Hong-Kong.

Die Wohnung fur das Existenzminimum: Chateau de La

Sarraz, 25-29 Juni, 1928. C.I.A.M.:

congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne (1979).

Kraus, Nendeln

FORINO I. (2019) – La cucina. Storia

culturale di un luogo domestico. Einaudi, Turin.

LE CORBUSIER, CERRI P., NICOLIN P. (edited by) (1973/2010)

– Verso un’architettura.

Longanesi, Milan.

LOOS A. (1972/2014) – Parole nel vuoto.

Adelphi, Milan.

MOLINARI L. (2020) – Le case che saremo.

Nottetempo, Milan.

NYS R. (2020) – “Fare architettura. La

prefabbricazioni

/ Making architecture. Prefabrication”. Domus, 1047, 66-73.

OTTOLINI G. (a cura di) (2010) – La Stanza.

Silvana Editoriale, Milan.

PURINI F. (2000) – Comporre

l’architettura. Laterza, Bari.

SAVORRA M. (2019) – “La casa

razionale”. In: F. Irace (edited by), Storie

d’interni. L’architettura

dello spazio domestico moderno. Carocci, Roma.

STRAPPA G. (1995) – Unità

dell’organismo architettonico. Note sulla formazione e

trasformazione dei caratteri degli edifici. Dedalo, Bari.

TEIGE K. (2002) – The minimum dwelling.

MIT Press, Cambridge. (Prima edizione 1932).

UGO V. (1986) – “Schema”. XY,

Dimensioni del disegno, 321/86, 21-32.