The creation of happiness. About Lina Bo Bardi’s

drawing

Caterina Lisini

Fig.

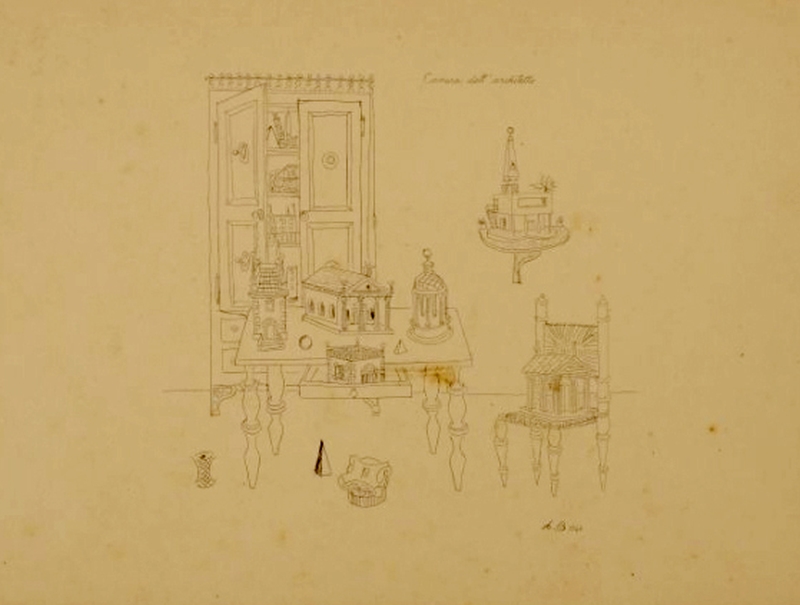

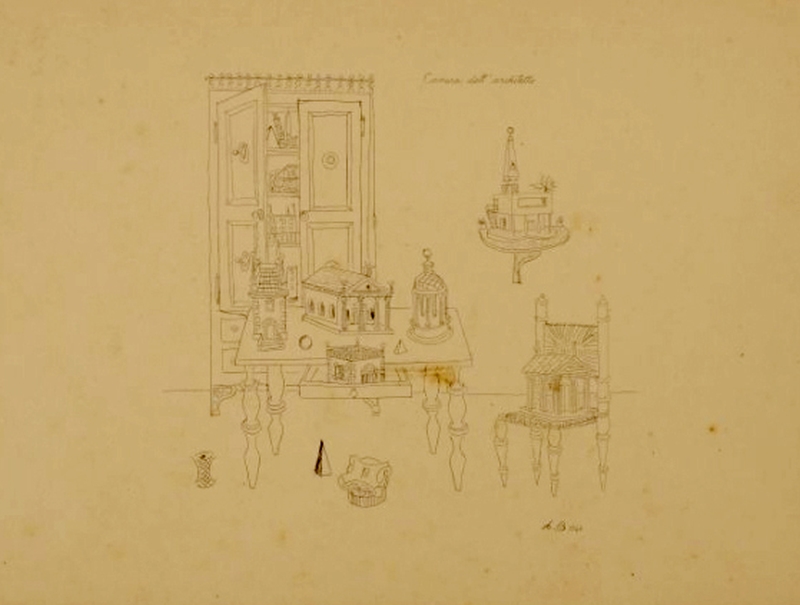

1 - Lina Bo Bardi, “Camera

dell’architetto” lithograph.

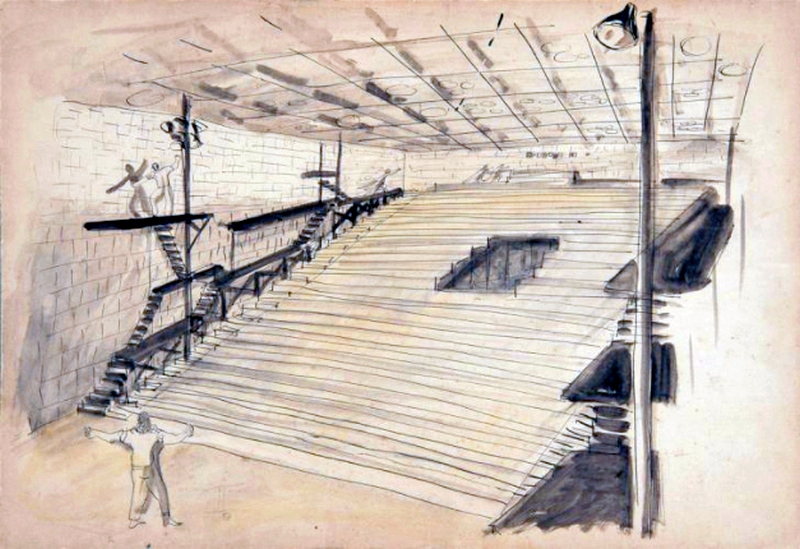

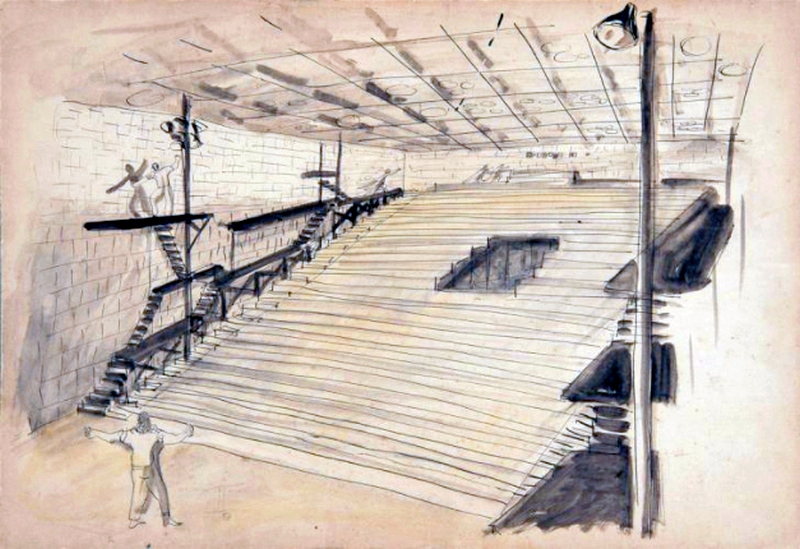

Fig.

2 - Lina Bo Bardi, MAMB Theater perspective.

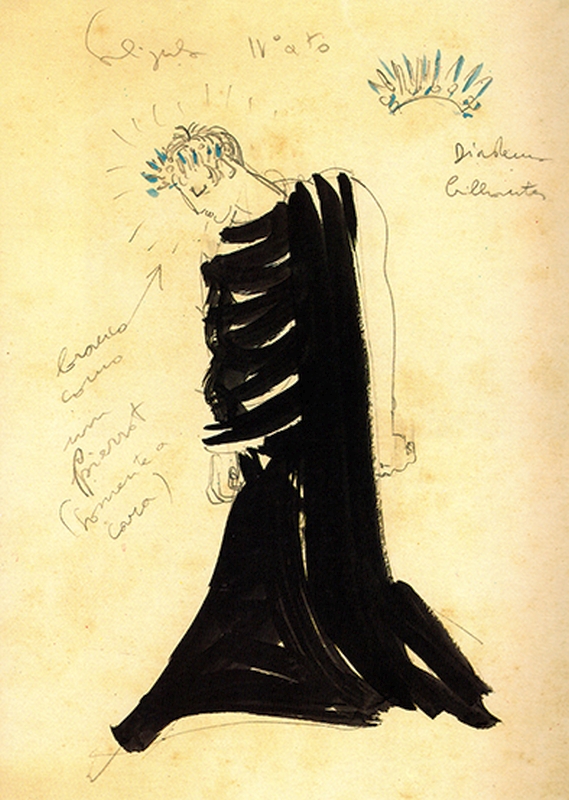

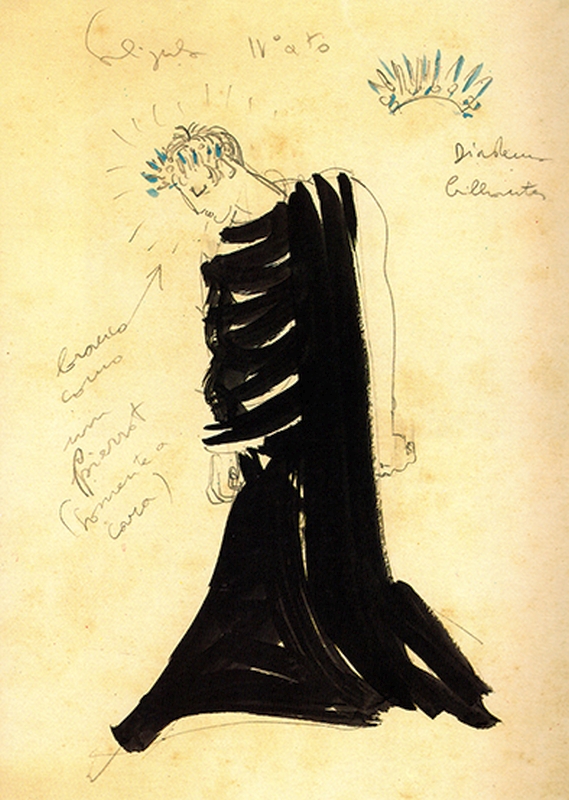

Fig.

3 - Lina Bo Bardi, study sketch for the stage costume for "Caligola".

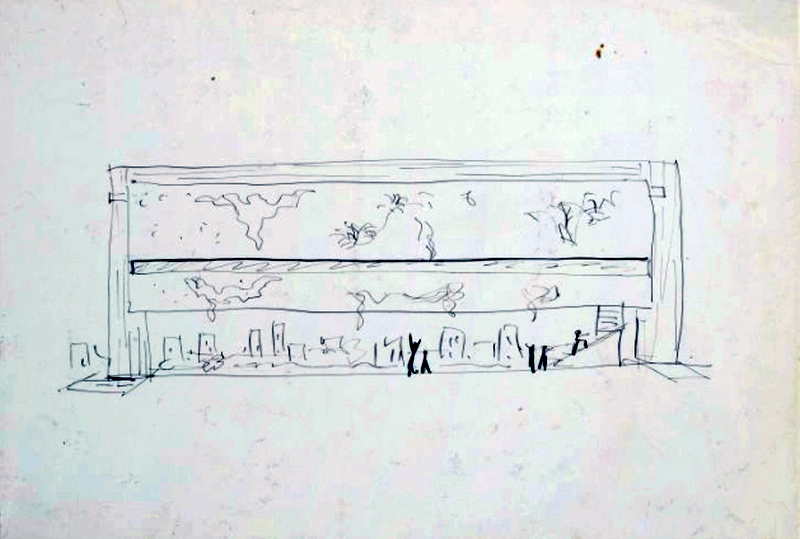

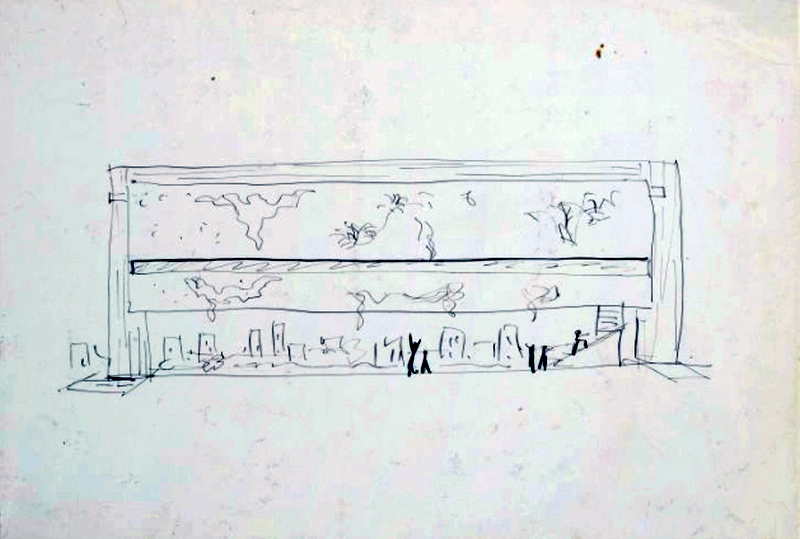

Fig.

4 - Lina Bo Bardi, MASP, study sketch for the facade.

Fig.

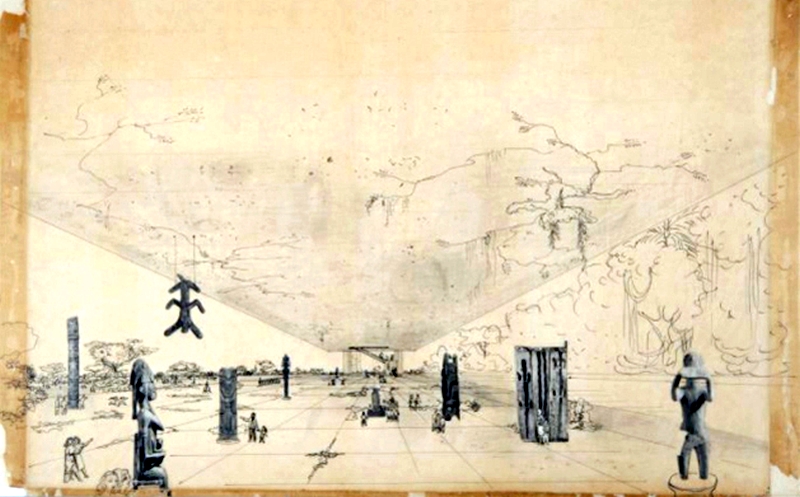

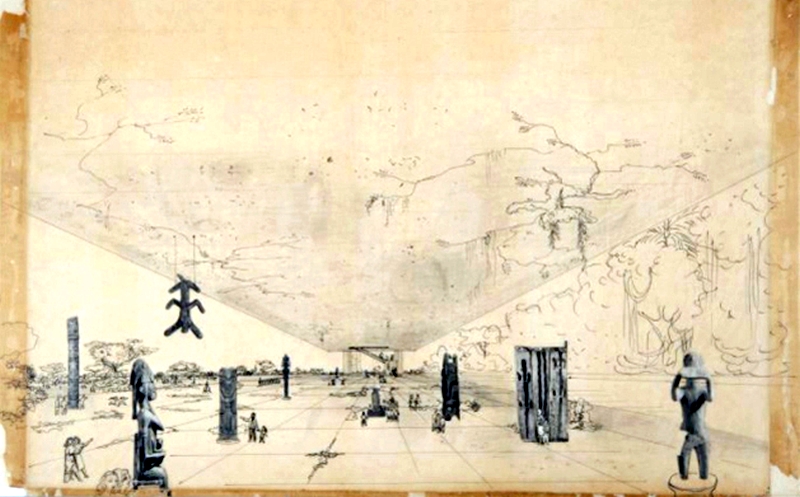

5 - Lina Bo Bardi, MASP, Belvedere perspective.

Fig.

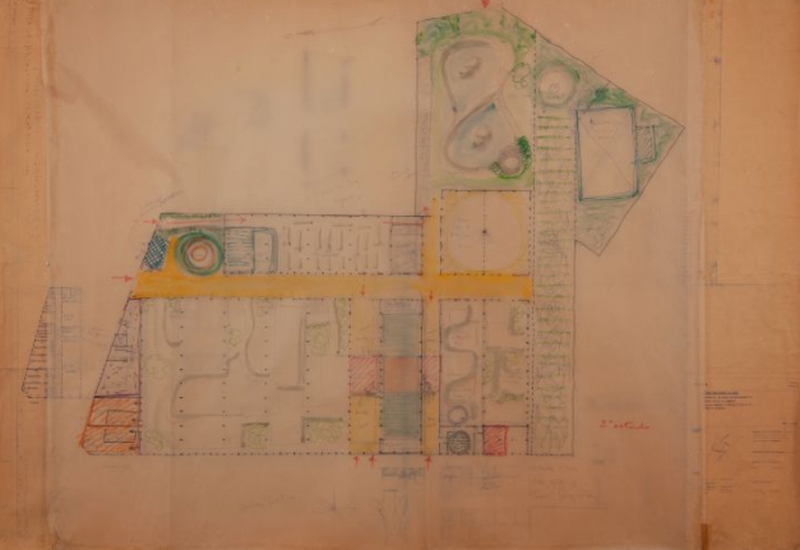

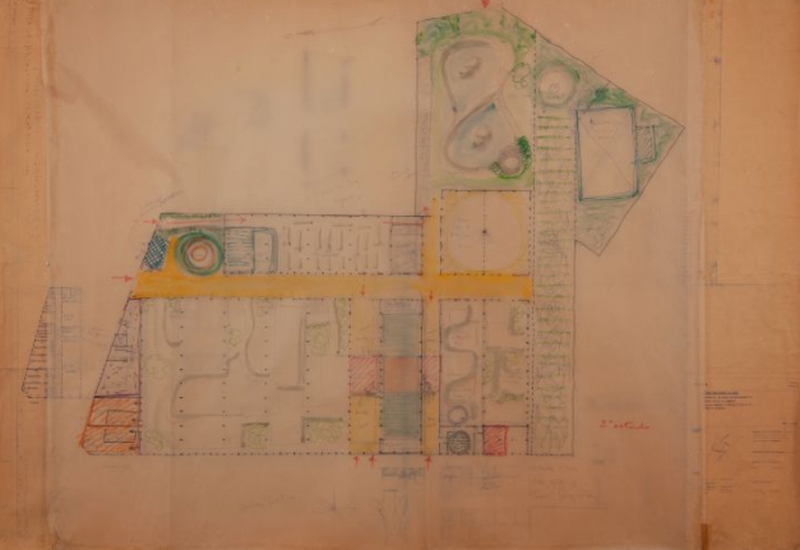

6 - Lina Bo Bardi, SESC da Pompéia, plan study.

Fig.

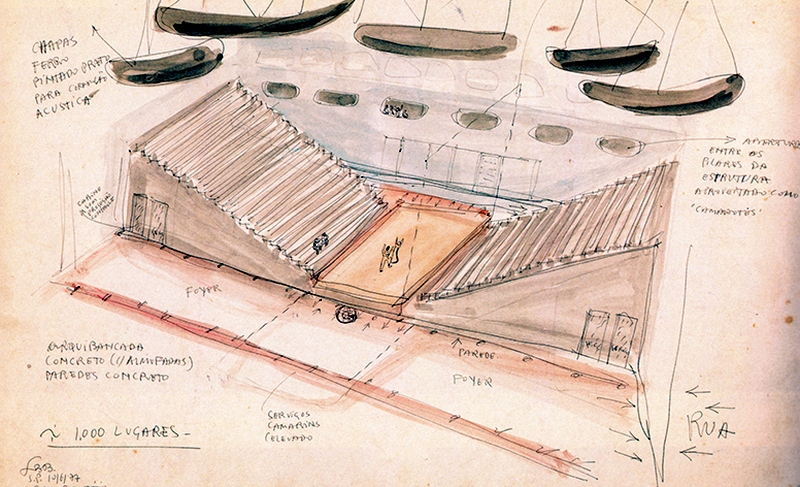

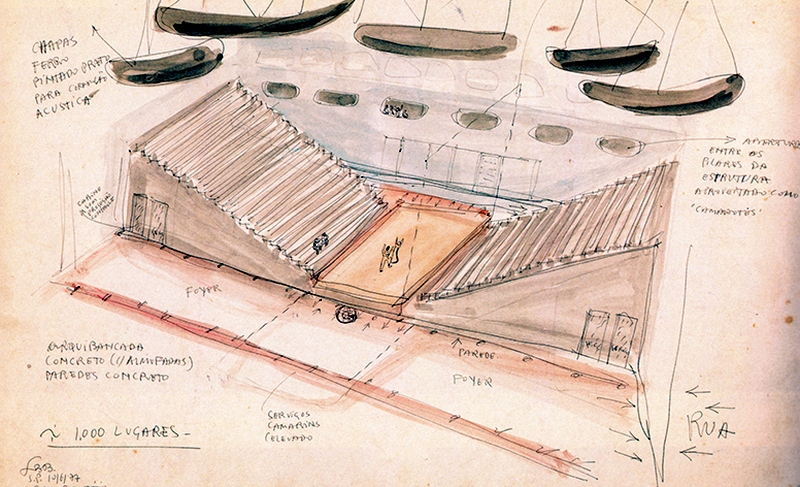

7 - Lina Bo Bardi, SESC da Pompéia, Theater perspective.

Fig.

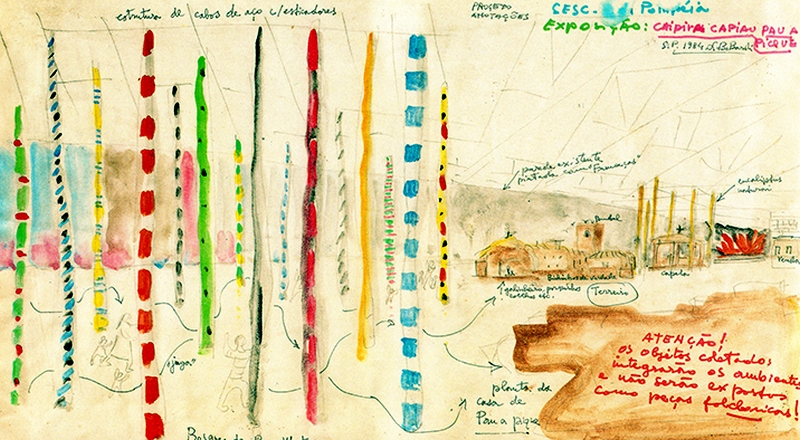

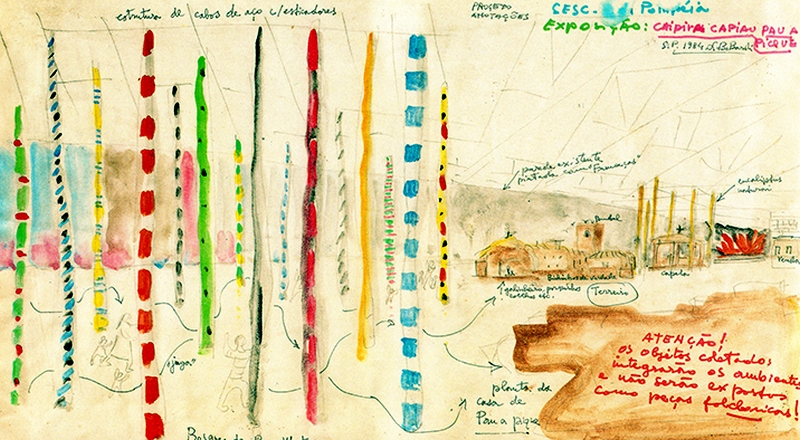

8 - Lina Bo Bardi, SESC da Pompéia, study sketch for the

exhibition “Caipiras, capiaus: pau-a-pique”.

«I am not interested in writing», Lina Bo

Bardi told Francesco Tentori with sober frankness, «I am

fully aware that I can write well. My masters are Stendhal and

Majakovsky. The former taught me conciseness, when he declared that he

had learned to write from the officers of the French building cadastre

and the drafters of the articles of the Civil Code. The second taught

me rhythm instead, the fantasy of the real» (Tentori 2004, p.

151).

Also drawing, seems to have in Bo Bardi a similar dual soul,

which results in an extraordinarily multiformity of fertile

significances. Not only, or not so much, architectural drawings,

technical drawings that are functional to the project, to its execution

or to the worksite. But neither simply conceptual drawings, study

sketches, theoretical or expressive research drawings. Nor merely

imaginative, perceptive or travel drawings. Her drawings, whose traits

are often somewhat naïve, but at times meticulously precise

and constructive, show a great variety of techniques, from pencil

sketches, gouache, watercolour, ink drawing, and

collage, and covering remarkably wide-ranging themes and scales, which

include simple objects, furniture, jewellery, clothing, individual

residential houses, housing estates, public buildings of great scale

and complexity, as well as theatrical sets and museum and exhibition

set-ups and mountings, as a whole seem to be marked by the apparent,

manifest oxymoron: «the fantasy of the real».

In August of 1942, while the war was in full swing, the

magazine «Domus», then under an emergency editorial

staff which included Melchiorre Bega, Massimo Bontempelli and Giuseppe

Pagano, asked «a group of architects to describe

[…] with intimate confidence, the ideal design of the house

of their dreams», an elusive theme, almost involving

«drawing the impossible» (Redaz. Domus 1942, p.

312), to such an extent that it was interpreted, in the many

‘confessions’ that followed (Banfi, Belgiojoso,

Zanuso, Cattaneo, Diotallevi and Marescotti, Cocchia, Bianchetti and

Pea, Mollino, Pica, and others) as a symbolic rationalist house, as a

spiritual abstract house, as a subject of pure escapism, or else as an

autobiographical fantasy. Among the many drawings which exist from Lina

Bo Bardi’s years of education and training, first in Rome and

then in Milan, a lithograph from 1943 entitled Camera

dell’architetto seems like it could belong to this

gallery of reflections, offering the ironic and meditative

self-portrait of a period of her life which is about to conclude, and

already revealing in a nutshell a constant of her work, that is the

deep interweaving between drawing and autobiography. On an unremarkable

wall, a stylish closet with half-open doors serves as a bourgeois

backdrop to a small table with turned legs, next to which stands a

traditional stuffed chair: the whole domestic space is crowded with a

multitude of architectural models, mostly fictional, where a Classical

temple and a Renaissance temple, a fragment of a Palladian villa and

elements of historic dwellings meet in the foreground, while an Ionic

capital lies on the ground next to abstract geometric shapes.

Silhouettes of more distinctive architecture emerge from the closet:

obelisks, a mediaeval tower, the leaning tower of Pisa, the Colosseum,

and on one side, isolated above a small shelf, sits the model of a

modern architecture, connoted by pilotis and a fenȇtre

en longueur, partially concealing a tall obelisk. Rather

than an allegory, the continuous line of the drawing, as in an

illustration which does not wish to show off any technical virtuosity,

seems to represent a merry jumble which dissolves the multiple

references from the architect’s cultural baggage into a light

image, placing them all together, without hierarchies, in a sort of

silent dialogue. The mark of the cultural orientation derived from her

collaboration, together with Carlo Pagani, in Gio Ponti’s

publishing enterprises during the years 1940-1943 is quite evident. She

was a habitual presence in the last year of “Domus”

before the war and collaborated with continuity on

“Stile”, where she wrote about furniture, interior

architecture, and dealing as well with illustration and graphics,

including the design of several covers of the magazine. She also

collaborated occasionally on other magazines of Ponti’s

group, such as “Aria d’Italia”,

“Bellezza”, and “Vetrina e

negozio”. However, by 1943 new concerns had taken hold Bo

Bardi’s life which seem to seep out of the sense of

suspension of the drawing: as a result of the dramatic events of the

war, the impasse of rationalism and the emerging

debates within the groups of young architects, as well as the encounter

with Pietro Maria Bardi, and the growing need to assert her personal

convictions, the classical and idyllic limits of Gio Ponti’s milieu

became too narrow for her.

The urgency of reality and a new awareness burst in:

«I saw the world around me, Bo Bardi wrote some years later,

only as an immediate reality, and not as an abstract literary

exercise» (Carvalho Ferraz 1994, p. 10).

In this way a vision of architecture and of human works took

shape that was always tenaciously adherent to reality, a reality which

became imbued with hope and vitality since Bo Bardi landed in 1946 in

Rio de Janeiro, the city that represents the heart of the Brazilian

spirit, and to which she responded with a spontaneous and impetuous

creativity – «furious» according to

Semerani (2012, p. 8) – that is inseparable from the

experience of the body and physicality of the real, exercised in

shaping rigorous designs which were immediately contaminated with

festive and ironic evocations.

«Architecture as inhabited, human space, wrote Bo

Bardi in the early Fifties, is a powerful reality, accountable for the

behaviour of man, accountable even for his happiness. And in this sense

the Modern Movement continues» (Carvalho Ferraz 1994, p. 86).

Among the drawings made for the Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia

(MAMB), which originated as part of her process of complex cultural

refounding matured during the years in Bahia and after her exploration

of the Brazilian Nordeste[1], those that stand out most are

the ones produced for the construction of the theatre «one of

the most direct means of cultural propaganda, since it contains all the

other arts» (Carvalho Ferraz 1994, p. 144). The perspective

of the audience cavea is sketched on one page,

with a few lines in pencil and ink, emphasised by the usual watercolour

brush strokes, to be built with simple wooden plank decks and enclosed

by a tangle of trellises and walkable stairs, which could also be used

for stage action, shaped almost as plant ramifications. There is no

formal adjectivation or superfluous scenography, as well as no

functional division between the space for the audience and technical

spaces, stage mechanisation is abolished and there is a continuity

between the theatrical representation and the audience, resulting from

the proximity of the improvised stage, with as backdrop the bareness of

the great structure of the Teatro Castro Alves, still partially

destroyed by the fire of 1958. A modern, simple, community theatre,

«poor yet violently emotional» (Carvalho Ferraz

1994, p. 144). Bo Bardi’s study sketches seem to appropriate

the profound simplification lesson[2] derived from her experience in

Bahia: in their traits there is no originality or gratuitous invention

but rather the constant search for the essential and an inclination for

‘poor’ and bare architecture, as well as for raw

and unfinished materials, which seems to spring directly from the

translation of the close link between human needs and their fulfilment,

between usefulness and beauty. In this case drawing for Bo Bardi is not

only a stage in her approach to the project, but becomes a social and

existential reflection, an expression, tout court,

of her poetics, that can be summarised, using her own words, in the

determined «anthropological research in the field of art

against aesthetic research» (Carvalho Ferraz 1994, p. 216).

And when her drawings become populated and enlivened with figures and

shapes, it is the reality of the Brazilian human environment and the

specific features of the target community that enter into action,

‘dirtying’ the sheet of paper with graftings and

contaminations. Thus in her work memory, the relationship with cultural

manifestations and popular traditions, is never nostalgic, a mere

revisiting of the past for its own sake, it is not even a critical act,

an inquiry into time in order to understand the art or the discipline

in question, it is rather a motion of continuous wonder, undertaken

almost through the eyes of a child, an amazement before a repository of

forms, a tangle of expressions and experiences, all human,

indispensable to nourish the imagery of her art.

There are numerous studies, distributed over a period of time

ranging from 1957 to 1966, for the solution of the facade of the great

gateway of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), iconically

suspended at one end of Avenida Nove de Juhlo. The version dearest to

Bo Bardi, which she tenaciously explored for a long time, envisaged the

elevated body of the Museum as a single mighty concrete monolith, lit

from above, materially dense and completely blind, except for a long

horizontal slit at the level of the temporary exhibitions, and entirely

embedded with plant inlays, drawing an irregular pattern of tropical

vegetation emerging «among the interstices of the raw

concrete, as if from the cracks in the stones of an old

cathedral» (Lima 2021, p. 259). As part of that same series

there is an unusual perspective of the Belvedere, traced precisely

under the imposing frame of the museum and aligned with it, to the

extent that it seems to stretch almost infinitely, which depicts, among

the efflorescence of the vegetation, sketched in pencil, a collage of

great tribal sculptures freely distributed throughout the vast space

and surrounded by visitors, almost as if probing the vision of a new

society capable of imagining a continuous overlapping of archaic

artistic manifestations and contemporary creativity.

Bo Bardi draws what she is thinking about and designing, in

fact she thinks by drawing and at the same time thinks by looking at

the world. What guides her hand, as in any true artist, seems to be

«the four-eyed head», imagined by the contemporary

artist Tullio Pericoli, «with its double set of eyes, one on

the forehead and one in the brain», the material eyesight and

that of the intellect which cannot do without each other, in the same

way that «it is not possible to see without involving the

heart and the mind» (2021, pp. 43, 41). Even in her more

specifically architectural drawings there is rarely anything conceptual

about them, far from being polished, there is something immediate,

spontaneous and vital in them, a kind of continuous flow between art

and life, almost as if they had been made only for herself –

Bo Bardi confessed: «I work during the night, when everyone

else is sleeping […] and all around me there is

silence» (Dos Santos 1993, p. 17) –, for the

urgency of putting her thoughts on paper as they are being formed.

There is in Lina’s drawings (this is how she is

affectionately known, still today, almost everywhere throughout Latin

America) a conflict, or rather the fruitful co-presence of a rational

inclination, on the one hand, which is well suited to her Eurocentric

education, and a surrealist tendency, on the other, which blends with

her instinctive attachment to popular culture, to myth, to the

ancestral rites of the local tradition: that

«enchantment», which she said she felt immediately

after arriving in Rio, «a real, not metaphysical hope found

almost on a daily basis in the simplicity of the architectural

solutions, in human salutations, things that were unheard of for a

generation that arrived from far away» (Carvalho Ferraz 1994,

p. 12).

Surrealism seems to completely take over the drawings of the

Leisure Centre SESC Fábrica da Pompéia, carved

out of the industrial suburbs of São Paulo by converting an

old metal drum factory. They show, through the huge number of sketches

and tests, Bo Bardi’s extraordinary capacity to hold together

the very different scales of the project, from the high cement

‘towers’ of the sports facilities, to the minute

design of the furnishings, the staff uniforms and even of the

advertising indications. «As in any Surrealist research, from

Savinio to Picasso, Breton, Buñuel or Jarry, it is the

images and materials which generate the composition through which the

mechanic and the organic, the pure and the impure, desire and chance

traverse the boundaries that separate them» (Semerani and

Gallo 2012, p. 29). Yet in the case of Bo Bardi a hermeneutic capacity

is added: it is an attitude which draws and stages «the

imperceptible rustle of life», which in turn seems to relate

her artistic path to that of a writer such as Natalia Ginzburg, another

extraordinary 20th century female figure who was

her contemporary. «It is the pleasure of using the mind as

the bowels, of having the mind walk in darkness, the journey and the

vicissitudes of intellectual knowledge being nothing more than the

slightly blackened mirror which reflects what in those depths [...] is

dark yet still legible» (Garboli 1989, pp. 116, 106). For

both probably an entirely feminine capacity for inclusion and

appropriation of the world, that in the case of Bo Bardi seems to guide

the steady hand with which sketches her creations.

From the first draft plans a theatre, symbol of life and

participation, is placed at the cross-shaped intersection of the long

open-air public paths that branch out from the Centre. A meaningful

perspective sketch shows, in the elongated rectangle of the former

warehouse, the completed layout for a modern theatre with a central

stage made entirely in cement, with the monolithic block of the two

cavea like terraced stands facing each other and surrounded by linear

balconies overhead which offer additional space for the audience, with

views from above and to the side of the stage, all of which animated by

the sculptural presence of large steel plates, silver in colour, in the

way of Calder’s Mobiles, hanging from

above and performing acoustic functions. All around, in the warehouses

liberated from all interior partitions, the spaces for recreational and

cultural activities are located, such as the library, workshops,

reading and children’s play spaces, as well as rest and

exhibition areas and the vast lounge with the carvings recalling a

watercourse and the foguiera – the

great fireplace –: all places for social interaction

interconnected and interwoven by way of a sought-after

‘chancefulness’ which reflects the unpredictable

nature of life. All of Bo Bardi’s drawings, full of voices

and colours, seem to spread-out in thousands of rivulets of intense

creativity that find expression even in the furnishings, such as the

austere theatre seats, entirely in solid wood, not stuffed or

upholstered in velvet as in 18th century court

theatres or in accordance to contemporary comfort standards, but rather

devised for «giving back to the theatre its capacity for both

distancing and engaging». The drawings, even those more

properly architectural, are never aimed at presenting a work or a

creation, at presenting a professional proposal, but are rather

intended as research and knowledge tools. A festive atmosphere, an

ironic cheerfulness, continuously hovers above them, that is

inseparable in Bo Bardi from a form of understanding or wisdom about

life, and which seems to summarise her peculiar and unique creation of

happiness. «Todos juntos»,

Lina wishes the recipients of her Sesc Pompéia to be,

«young people, children, senior citizens, all united in the

pleasure of getting together, of dancing and singing» (Bo

Bardi 1992, p. 225).

Notes

[1]

Lina Bo Bardi went to Salvador de Bahia for the first time in February

1958. She returned in 1959 and remained there until August 1964, a few

months after the military coup d’état.

On these experience she published an article in 1967 entitled Cinco

anos entre os brancos (“Mirantes das artes

etc”, 6, November – December), later translated in Cinque

anni tra i bianchi (Carvalho Ferraz, 1994, pp. 161-162).

[2]

On the meaning of ‘simplification’ for Lina Bo

Bardi see her words in the writings Museu de Arte de

São Paulo and Mostra Nordest (Carvalho

Ferraz 1994, pp. 100 and 158).

References

BO BARDI L. (1953) – “Museo sulla sponda

dell’oceano”. Domus, 286, 15.

BO BARDI L. (1974) – “Sulla linguistica

architettonica”. L’Architettura, 226.

BO BARDI L. (1987) – “Centre

Socio-Culturel SESC Pompéia”.

L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 251,

6-9.

BO BARDI L. (1992) – “Centro de Lazer SESC

“Fábrica da Pompéia, São

Paulo, Brazil, 1981-89”. Zodiac, 8, 224-229.

CARVALHO FERRAZ M., (edited by) (1994) – Lina

Bo Bardi. Charta-ILBPMB, Milan-São

Paulo.

CRICONIA A., (ed.) (2017) – Lina Bo

Bardi. Un’architettura tra Italia e Brasile.

Franco Angeli, Milan.

DE OLIVEIRA O. (2000) – “Lina Bo Bardi,

architetture senza età e senza tempo”. Casabella,

681, 36-55.

DOS SANTOS R. C. (1993) – “Lina Bo Bardi:

l’ultima lezione”, interview. Domus, 753,

17-24.

GALLO A. (edited by) (2004) – Lina Bo

Bardi architetto. Marsilio, Venice.

GARBOLI C. (1989) – Scritti servili.

Einaudi, Turin.

LIMA ZEULER R. M. DE A. (2019) – Lina Bo

Bardi, Drawings. Princeton University Press, New Jersey,

USA.

LIMA ZEULER R. M. DE A. (2021) – La dea

stanca. Vita di Lina Bo Bardi. Johan & Levi Editore,

Milan.

MAGNAGO LAMPUGNANI V. (1990) – “Centro

sociale e sportivo «Fabbrica Pompéia»,

San Paolo”. Domus, 717, 50-57.

PERICOLI T. (2021) – Arte a parte.

Adelphi, Milan.

PONTI G. (1953) – “Casa de

Vidro”. Domus, 279, 19-26.

REDAZ. DOMUS (1942) – “La casa e

l’ideale”. Domus, 176, 312.

SEMERANI L. AND GALLO A. (2012) – Lina Bo

Bardi. Il diritto al brutto e il SESC-Fàbrica da

Pompéia. Clean, Naples.

TENTORI F. (2004) – “Ricordo della Signora

Lina”. In: Gallo A., (ed.) – Lina Bo

Bardi architetto. Marsilio, Venice.