From the mind to the sheet, through the hand.

Topicality of freehand sketching in the architectural

project.

Chiara Vernizzi

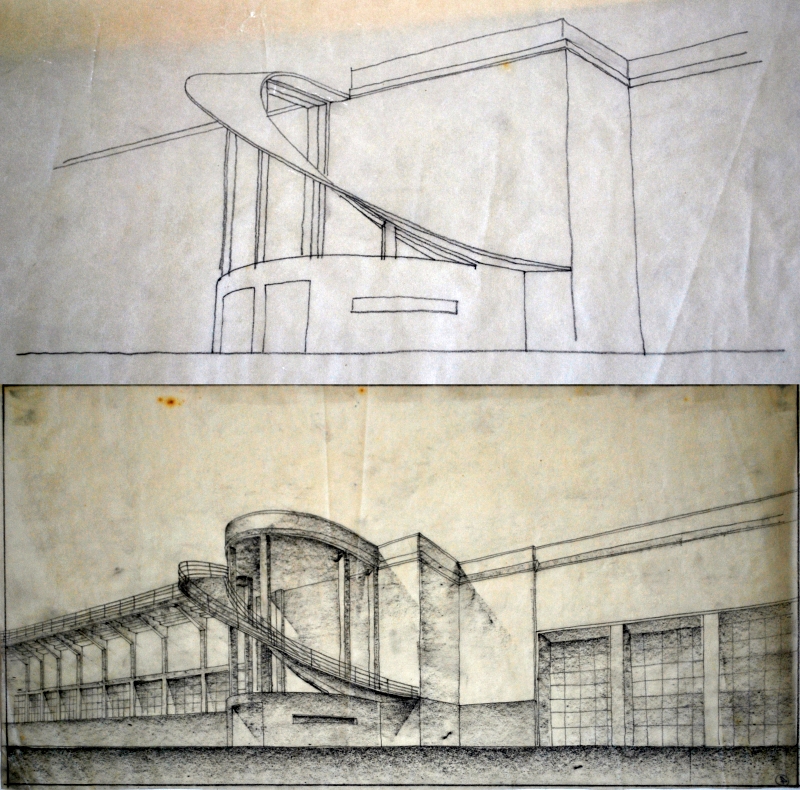

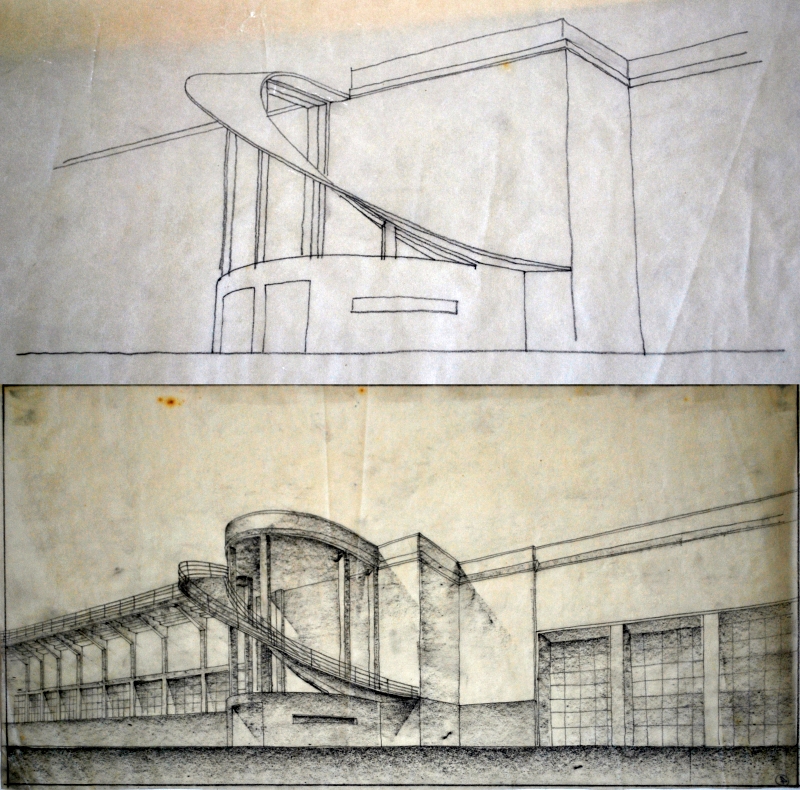

Fig.

1 - Pier Luigi Nervi, Stadio Comunale Berta di Firenze (1929/32).

Exterior of the grandstands at the spiral staircase. Perspective sketch

and incidental perspective. . CSAC Università di

Parma, - N. inv. PRA 31 – n. id. 12814 – coll.

268/6 e 268/8.

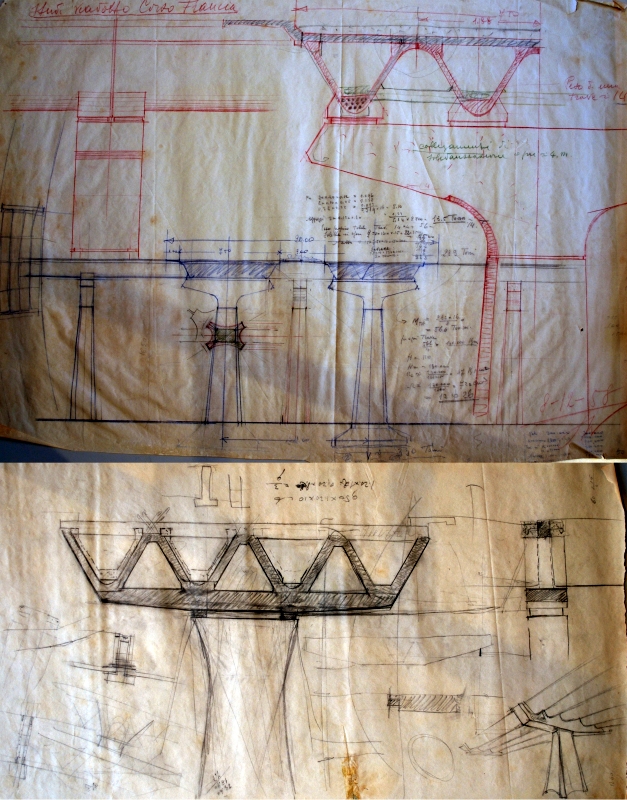

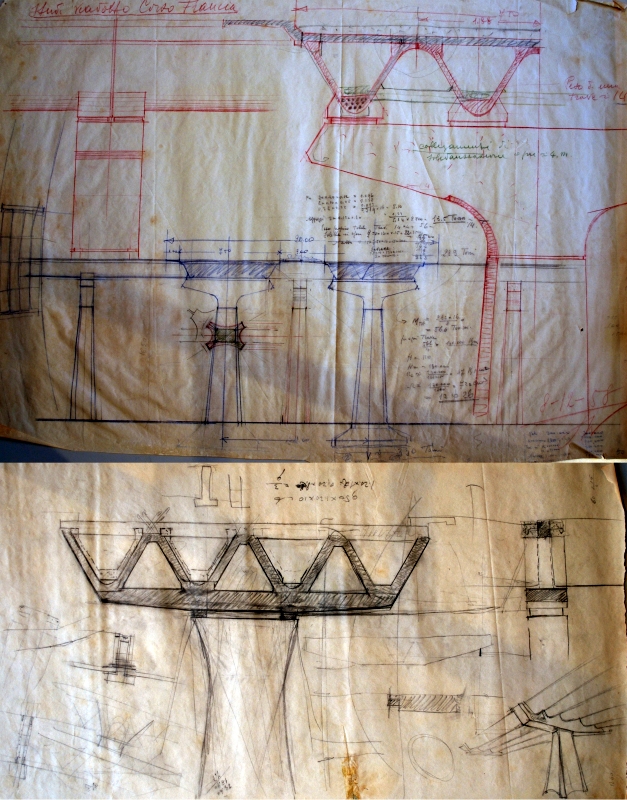

Fig.

2 - Pier Luigi Nervi, Viadotto di Corso Francia a Roma (1958/60).

Overall and detail sketches, perspective and orthogonal projections. .

CSAC Università di Parma, - N. inv. PRA 1252

– n. id. 15254 – coll. 31/6.

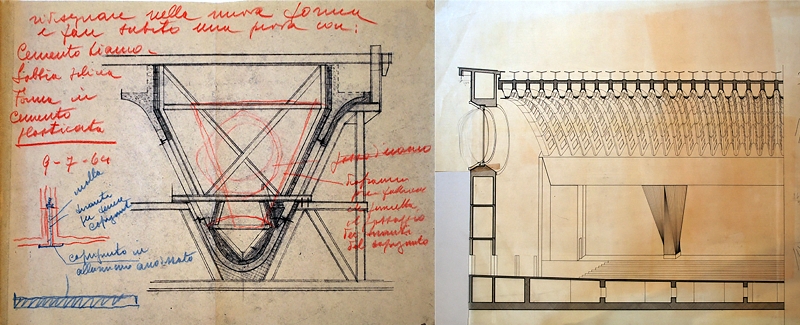

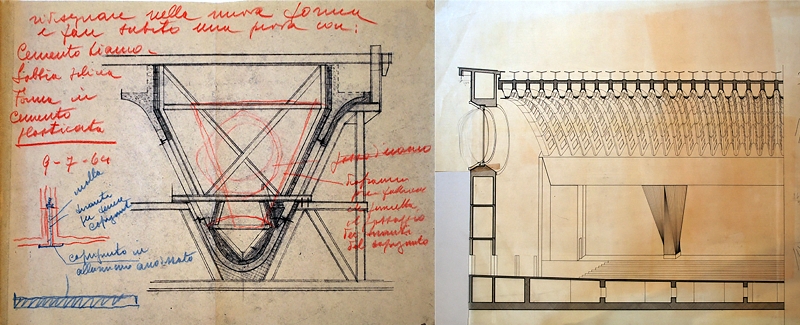

Fig.

3 - Pier Luigi Nervi, Aula per le Udienze Pontificie in Vaticano

(1966/71). Detail of the covering vault of the courtroom and executive.

CSAC Università di Parma, - N. inv. PRA 585

– n. id. 14142 – coll. 152/4.

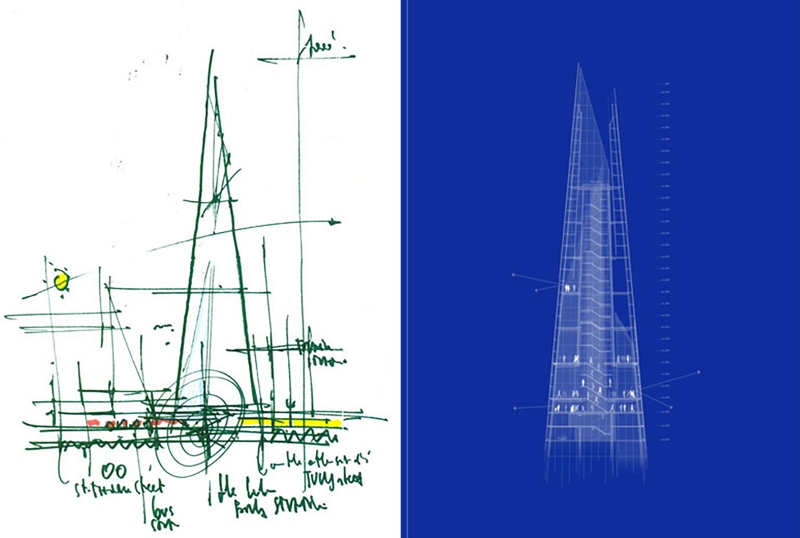

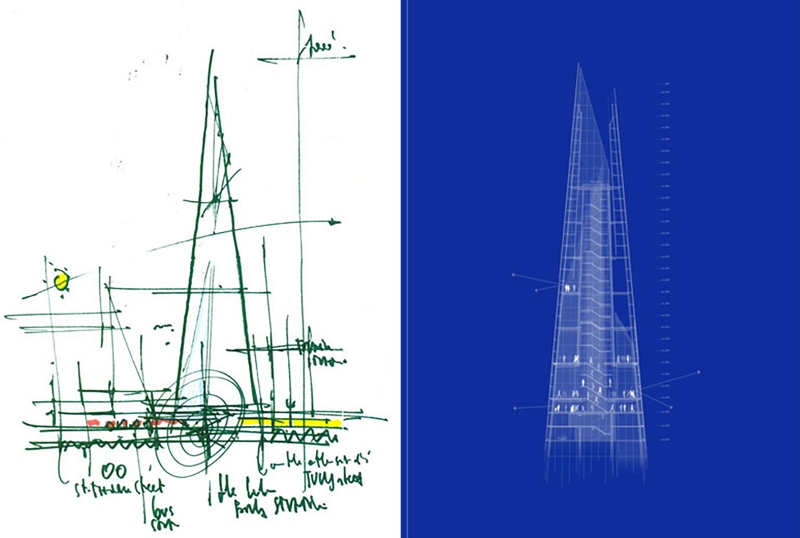

Fig.

4 - Renzo Piano, Centro Culturale Jean-Marie Tjibaou, Nuova Caledonia

(1991-1998). Concept sketch and project section. Fondazione Renzo

Piano www.fondazionerenzopiano.org

Fig.

5 - Renzo Piano, the Shard, London Bridge Tower, Londra (2000-2008).

Concept sketch and project section. Fondazione Renzo Piano

www.fondazionerenzopiano.org

Introduction

The Oxford Dictionary defines the term concept as

«an abstract idea», but also as «a

project or an intention», or philosophically declines it as

«an idea or a mental image that corresponds to some distinct

entities or to their essential features…».

From this definition begins a reflection on the role that the

term assumes in the design field, focusing attention on the project

sketch as the primary outcome of the process of defining the idea. By

way of example, we will analyse the outcomes of the approaches of two

central figures in the panorama of the architectural project, despite

their strong differences in the graphic and design results.

From the study of the drawings conserved at the Nervi Fund at

the CSAC of the University of Parma and from the observation of some

sketches by Renzo Piano exhibited at the Renzo Piano Foundation in

Pegli (Genoa), the following considerations take place, recalling that

Vasari wrote already in the second half of the sixteenth century:

we call “sketches” a first kind of

drawings made to find the way of attitudes and the first composition of

the work. We made them in the form of a stain, only outlined in a

single draft of the whole.

The engaging rereading of the Italian translation of Paolo

Belardi’s short text entitled Why Architects still

draw, also urged a re-reading of the founding role of the

design sketch as a moment to draw the idea from oneself and its

subsequent development, outlining a moment of intimate dialogue,

preliminary to any further accurate definition of the architectural

work.

It is also impossible not to recall Franco Purini’s

numerous reflections on drawing, which is portrayed as an ideal square

that contains four main aspects: seeing, thinking,

communicating, remembering. (Purini in Disegnare 2010, p.

14). In particular, he emphasizes that on the one hand drawing leads to

thinking and on the other it is itself the result of thinking, that is,

the result of that internal design to which Federico Zuccari refers:

the outcome of the interaction between thought and hand (Docci in

Disegnare 2010, p. 3).

Of particular interest, following the reflection on the

sketch, is also the comparison between the preliminary sketches of a

work and its final version, in search of the geometries present since

the first conceptual drawings and their transformation into

architecture. For this reason, some sketches are displayed in sequence

at the Renzo Piano Foundation alongside the final (or executive)

drawing and photographic images of the architectures actually built,

allowing for a comparison between the concreteness of the realization

and its creative roots.

On several occasions, Renzo Piano has said that he makes very

complex buildings, but always draws by hand to learn about the object

he works on. This statement already contains all the meaning of

freehand drawing intended as an immediate extension of the mind, but

also as an instrument of knowledge, of inner debate, of definition and

refinement of the idea. Sketches are often crooked, sometimes

inaccurate and disproportionate, always out of scale, with projective

methods used in an intuitive and not rigorous way, but which, also in

the spontaneous elaboration, always emerge for those who have studied

artistic and architectural disciplines. In fact, we know that the

project design makes use of codes and rules that make it a real

language.

While in the initial phase of the design process, drawing is

configured as a tool for communicating the designer’s ideas

and, as such, it can also take on very personalized forms, vice versa

the executive drawing has a strictly communicative function and it must

be organized through a coded language, with its own vocabulary and

syntax.

The effectiveness of the sketches lies in their being drawn

freehand, without aids such as rulers, by hand movements that are

sometimes uncertain and often accompanied by textual annotations with

which they are intertwined, outlining a diachronic and evolutionary

inventive process (Dal Co in Conforti, Dal Co 2007, p. 23).

The sketches become work tools whose outcomes should be

studied as real archival documents, as every interpretation of an

architecture should start from the analysis of the multiple layers that

are deposited there during the creative process. The various documents

must be analyzed to find the sedimentation of the processes of

conception and selection that make effective the functional and

(sometimes) symbolic purpose they pursue (Dal Co, ibid.).

In fact, according to Manfredo Tafuri:

«architectural drawings are to be interpreted precisely as

archaeological traces, from which the text is decomposed»

(Tafuri in C.S.A.C. 983, p. 24).

While Dorfles says that he considers it necessary to judge the

Architectural Design as an artistic operation in its own right, free

from what may be the characteristics of the building that may be built

at a later time, on the basis of the primitive drawing (Dorlfes in

C.S.A.C. 1983, pag. 34).

The authors and the cultural background

The approach to the project of the two authors, Pier Luigi Nervi and

Renzo Piano, is therefore read through the analysis of what is the

contribution and development of the primitive idea, in its evolution

carried out through the direct, manual graphic tool, intended not only

as a communicative medium, but also (and above all) as a moment of

verification, maturation and knowledge of the project idea in an

intimate and personal dialogue. Gradually the idea (the concept)

is transformed into something that must be communicated through a coded

language, giving life to graphic drawings drawn up according to the

current regulations, through which the realization of the work is

described. They are objective documents capable of uniquely

communicating the intentions of the designer.

Several critics, architectural historians and designers have

spoken out on the controversial question of the intrinsic value of

architectural drawing and sketch, understood as a finished work in

itself. For this reason, an overview of the main interpretations in

this sense is necessary when you are about to read and interpret the

graphic corpus of authors such as Pier Luigi Nervi and Renzo Piano. On

the one hand to contextualize works in a never exhausted cultural

debate, but also to contribute to the correct interpretation of the

graphs with the necessary critical tools.

Luigi Grassi applies the Crocian distinction between art

and non-art to architectural drawing and

considers worthy of attention only the drawing by the

artist’s hand, while the executive drawings aren’t.

Bruno Zevi also set against the original drawings with the project

bords and implements a distinction between a work of art and

professional drawing. On the other hand, Renato De Fusco, applies the

results of linguistic structuralism to the study of architecture and he

considers architectural drawing as a language, without, however,

considering the different writings of drawing. Vittorio Gregotti

carefully evaluates the design intention and emphasizes the

relationship between the preference for certain means of representation

and the cultures of the project. Luigi Vagnetti proposes to document

the transformation of the graphic language of architects and engineers

and to understand the historical components of the graphic tool; for

him there is no analogical relationship between graphic representation

and realized architecture. Klaus Koenig and Tomàs Maldonado

differently deal with the problem of the relationship between drawing

and design iter. Instead, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani relates the

«form of presentation» to the

«intellectual purpose of the author».

A key moment in the debate is the conference on architectural

drawing organized by the CSAC Centro

Studi e Archivio della Comunicazione of the University of

Parma in October 1980. On this occasion, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle

historically identified and contextualized the interpretative models

that had given rise to the different readings of the project drawing:

the design seen only as a function of the work carried out versus the

drawing considered as an autonomous value.

The reading of the graphic works by Pier Luigi Nervi and Renzo

Piano refers to this variegated cultural panorama. They have left us an

extraordinary body of drawings that includes sketches, preliminary and

final designs and a very large number of executive drawings and

isometric and perspective views.

In light of these different interpretations expressed by

historians and critics of architecture, the problem of

“writings” and their history has been tackled by

carefully considering the graphics chosen by the two authors,

identifying variations both between contemporary projects and over the

course of the long period examined. The examination of the

“writings” proved to be particularly important for

understanding the complex system of relationships between the designer

and the culture of his time.

The analysis carried out on Pier Luigi Nervi’s

drawings was set up by dividing the documents relating to the projects

examined by horizontally investigating the projects, focusing on the

analysis of the graphic aspects expressed in Nervi’s

autographed drawings. In particular, the sketches were seen that can be

traced back at the first creative moment and that dimension the

structural parts or others, but also those that control the

relationship between the context and the new architecture.

The sketches by Pier Luigi Nervi, referable to the copious

documentation preserved in Fondo Nervi at CSAC in

Parma, are mostly made up of minute line notations, almost always

accompanied by notes and dimensions, and they oscillate between the

pure structural intuition and the precise solution of construction

problems (Figg. 1-2).

The sign, almost always drawn in pencil, is always precise and

clear, and it denotes the author’s strong personality as well

as an excellent command of the instruments of representation. Attention

is always aimed specifically at definite themes, investigated according

to adequate projective codes and differentiated graphic signs always

used in a conscious way. They’re aimed at defining a personal

language which, together with descriptive annotations or captions, fix

the attention specifically to constructive, formal or perceptive

aspects of the work (Fig. 3).

Renzo Piano’s drawings, kept at the Fondazione

Piano in Genova outline an inimitable style thanks to the

peculiarity of their graphic aspect. The sign, no less than the

writing, is always clear and fast, constant and sure. The graphic

variation is functional when the themes vary. His drawings illustrate

how much Piano is aimed at the search for coherence between form and

structure, of the structural and formal conception, aiming to integrate

composition and construction together, fully accepting, albeit with

very different formal and structural outcomes, the lesson by Pier Luigi

Nervi.

The use of different tools in the definition of the creative

sketches mostly sees the pencil (Pier Luigi Nervi often also uses red

or blue pencil to correct the first lines), but also black or coloured

marker (often green for Renzo Piano), with different thickness.

Occasional annotations enrich the graphic with hints; the studies,

albeit schematic, consider from the earliest stages the orientation in

relation to sun exposure.

Quick sketches are overwhelmed made of a few lines, sometimes

more accurate and defined. In any case, they tell us about the

architectural poetics and design language of the architect, expressed

in harmony with the final codified graphic, that is the true stylistic

code of the studio and its owner (Figg. 4-5). The notes and the

corrections are often also on the first prints (or copies) of the

project drawn up in definitive form, a sign of a constant work of

refinement of the idea, along the lines of what the masters of the past

(i.e. Pier Luigi Nervi) used to do. Then, they used to give the

drawings to the studio collaborators, who developed the ideas by

translating them into graphic boards drawn up according to the

normalized and unified codes and representation scales.

Claudia Conforti identifies in Renzo Piano’s

sketches:

three scales attacked simultaneously by the design signs: the

organic one of the artifacts, captured by the orthogonal sections

and/or perspective; that of the technical detail, which expresses

formal evidence of the space and its construction transferred into

sections; and the wide-ranging geographical one, which controls the

impact of the new building on the site. Only the latter is shown in the

final planimetric representation, in which the project is at the centre

of a network of relationships that the architect has carefully studied

(Conforti 2007, pp. 7-8)

A trait that unites the sketches of the two authors, despite

the very different graphic and architectural outcomes, is the

coexistence of indications and annotations regarding solutions

referring to multiscale readings, highlighting the relationship between

constructive facts and perceptive results, to which both devote great

attention from the first creative phases. In many sketches of both

authors, indications on the assembly of the elements appear, an aspect

towards which a great deal of attention is shown already in the early

design phases, outlining a way of conceiving architecture that treats

form and structure together, which thinks of one not as a function of

the other, but as two entities and aspects that belong and

interpenetrate, effectively coinciding in the architectural products

designed.

In both of them, we know how much the search for

non-standardized structural and constructive solutions is a stylistic

feature of their architectural creations, while underlining once again

the difference of the final architectures, of the materials used and

also of the graphic results of the respective approaches to the

conceptual sketch and to the building process of the project that is

articulated through it.

Conclusions

It is well known that the advent of information technology, several

decades ago, led architectural drawing to broaden its boundaries,

progressively modifying the design process and amplifying the

expressive tools of architectural composition, becoming at the same

time a means of representation and a tool for development and control

of the design process. The peculiarity is that in this process,

information technologies have not remained functional to the

expressiveness of the idea, but they became a means of extending

projects and, consequently, a means of creating a new architectural

language.

The innovative trends in digital representation can be traced

back to three distinct aspects, respectively relating to the

verification and immediate use of the project model, that is the

creation of a 3D environment in which the designer can immerse himself

in a virtual experience; the communicability of the project itself and

its adaptation to the means and expressive tools of the contemporary

world, characterized by multimedia and multidimensionality; and above

all at the overwhelming entry of the IT into the ideational and design

process, suggesting, supporting and sometimes determining spaces and

geometries of the future reality, without making the phase of freehand

conceptual sketches obsolete.

The moment in which the idea of the form of the project

germinates and comes to be defined, always allows the authors to

express themselves in a totally subjective way and often freed from the

rigidity of the codes and rules of representation of the project,

sometimes giving life to real graphic languages or

“Metagraphic”, through which design creativity

gives life to a complicated game of remakes and inventions, in that

complex and patient game of textures that leads to the creative sketch.

The moment in which the idea of the form of the project

germinates and comes to be defined, always allows the authors to

express themselves in a totally subjective way and freed from the

rigidity of the codes and rules of representation of the project.

Sometimes this creates real graphic or

“metagraphic”) languages, through which the

creativity gives life to a complicated game of remakes and inventions,

in a complex and patient game of textures that leads to the sketch.

Concepts well expressed by Mario Botta, that well emphasizes

the cultural, meditative and formative role that still today the

freehand drawing must have in the preliminary ideational phases. In one

of his recent writings, he says:

With the passage of time the pencil has been transformed in an

extension of the hand itself, and he became used to having it between

their fingers, as happens with a smoker’s cigarette. The

pencil is not just a tool for drawing, but it helps to interpose the

pauses, it prepares the thought: it can perhaps be said that a pencil

is the tool that transports the idea to the drawing... it is a

research, not a representation tool (Botta 2020, p. 7).

References

BELARDI P. (2015) – Why architects still

draw. Casa Editrice Libria, Melfi.

BOTTA M. (2020) – Il disegno momento di

studio e confronto. In “Disegnare idee

immagini”, Anno XXXI, n. 61/2020. Gangemi editore, Rome.

CONFORTI C., DAL CO F. (edited by) (2007) – Renzo

Piano. Gli schizzi. Electa, Milan.

CONFORTI C. (2007) – “La dea della

bilancia e gli schizzi di Renzo Piano”. In: C. Conforti, F.

Dal Co (edited by), Renzo Piano. Gli schizzi.

Electa, Milan.

C.S.A.C. (1983) – Il Disegno

dell’Architettura. Incontri di lavoro. 1980.

Dipartimento Progetto, Quaderni 57. Grafiche STEP, Parma.

DE FUSCO R. (1966) – “Il Disegno

d’architettura”. Op. Cit. n. 6, Rome.

DOCCI M. (2010) – “Editoriale”.

Disegnare idee immagini, Anno XXI, n. 40/2010. Gangemi editore, Rome,

3-4.

GRASSI L. (1947) – Storia del Disegno,

Dott. G: Bardi- Editore, Rome.

GREGOTTI V. (1966) – Il territorio

dell’architettura. Feltrinelli, Milano.

DE RUBERTIS R. (1994) – Il disegno

dell’architettura. NIS, Rome.

KOENIG G. K. (1962) – “Disegno, disegno di

progetto e disegno di rilievo”. Quaderno n. 1

dell’Istituto degli elementi di Architettura e rilievo dei

monumenti, Università di Firenze, Florence.

MAGNAGO LAMPUGNANI V. (1985) – L’Avventura

delle idee nell’architettura 1750-1980, XVII Triennale. Electa,

Milan.

MALDONADO T. (1974) – “Architettura e

linguaggio”. Casabella n. 429, 9-30.

MEZZETTI C. (edited by) (2003) – Il

Disegno dell’architettura italiana nel XX Secolo.

Edizioni Kappa, Rome.

PURINI F. (1996) – Una lezione sul disegno.

Gangemi, Rome.

PURINI F. (2010) – “Un quadrato

ideale”. Disegnare idee immagini, Anno XXI, n. 40/2010.

Gangemi editore, Rome, 12-25.

VAGNETTI L. (1965) – Il linguaggio

grafico dell’architetto oggi. Vitali e Ghianda,

Genova.

VERNIZZI C. (2011) – Il disegno in Pier

Luigi Nervi. Dal dettaglio della materia alla percezione dello spazio.

Mattioli 1885, Fidenza (PR).

ZEVI B. (1972) – Architettura in nuce.

Sansoni, Florence.