Experiences of critical regionalism in China

Nicola Pagnano

Fig.

1 - Traditional house of a village. Clay and mud walls mix with natural fibres, Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (© Pagnano)

Fig.

2 - Traditional house of a village. Clay and mud walls mix with natural fibres, Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (© Pagnano).

Fig.

3 - Sundry clay bricks. Inner Mongolia, China 2007.

(© Pagnano)

Fig.

4 - Door entrance of a traditional house of a village in Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (© Pagnano)

Fig.

5 - Pigsty. Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (© Pagnano).

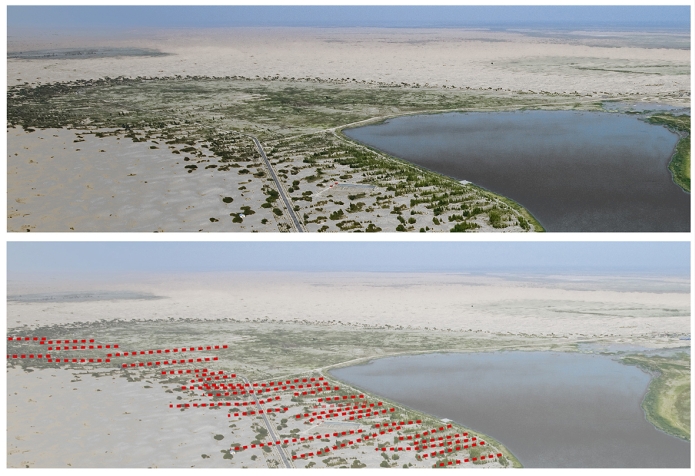

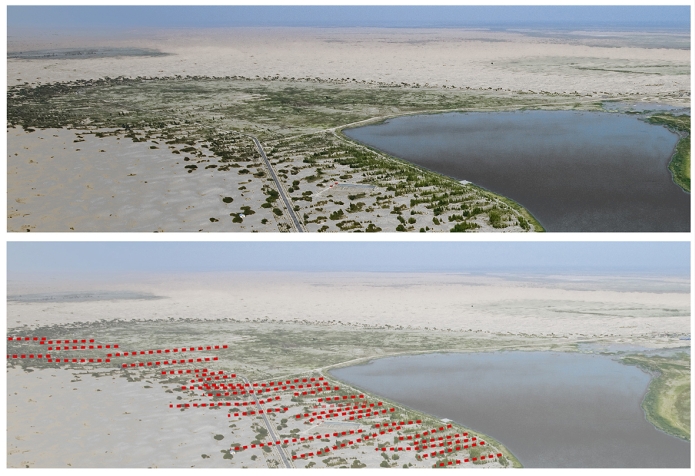

Figg.

6a-b - Top Aerial view of the project site; aerial view of the project

site with landscape paths. Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (©

Pagnano).

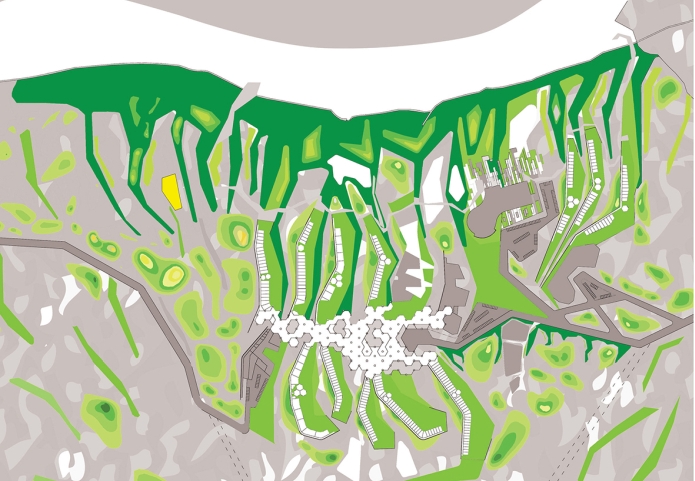

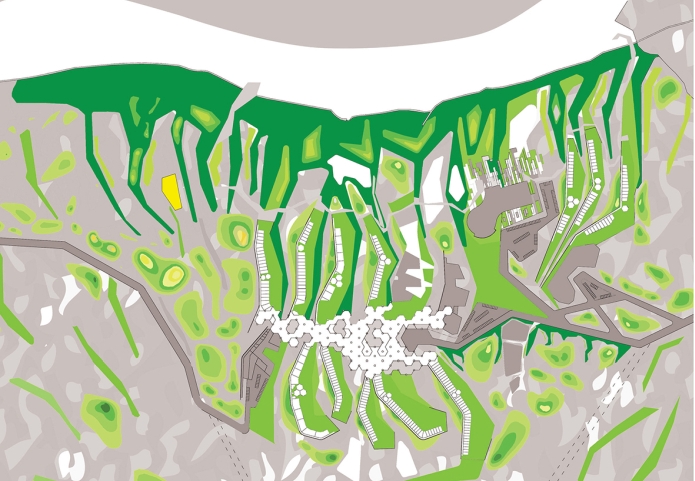

Fig.

7 - Planimetry of the Resort, dark green colour indicates the existing vegetation. Inner Mongolia, China 2007. (©

Pagnano).

Fig.

8 - Bird-eye view of the resort. Inner Mongolia, China 2007.

Fig.

9 - Project site of a resort. Pu Er, Yunnan, Bai Ma Shan Mountain, China 2011. (© Pagnano).

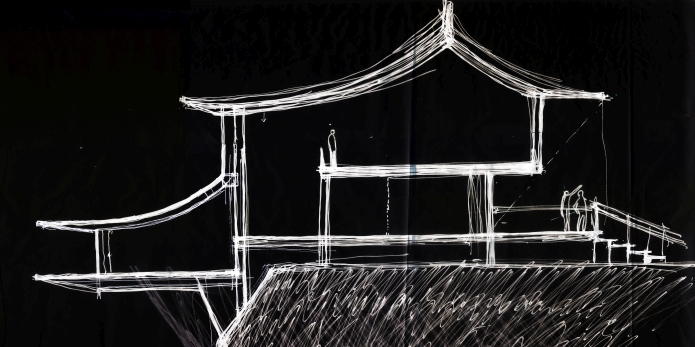

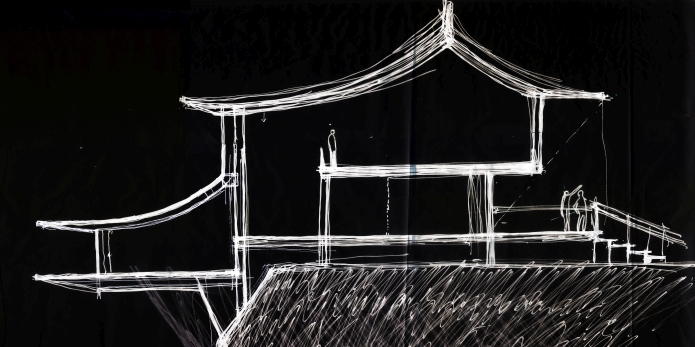

Fig.

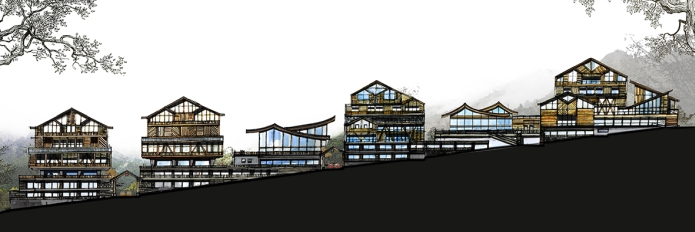

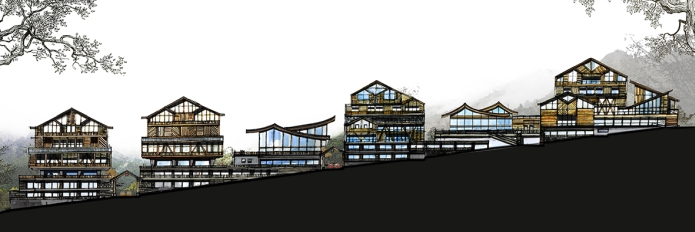

10 - Section sketch of one unit of the resort. Pu Er, Yunnan, Bai Ma Shan Mountain, China 2011.

Fig.

11 - 3d realistic view of one unit of the resort. Pu Er, Yunnan, Bai Ma Shan Mountain, China 2011.

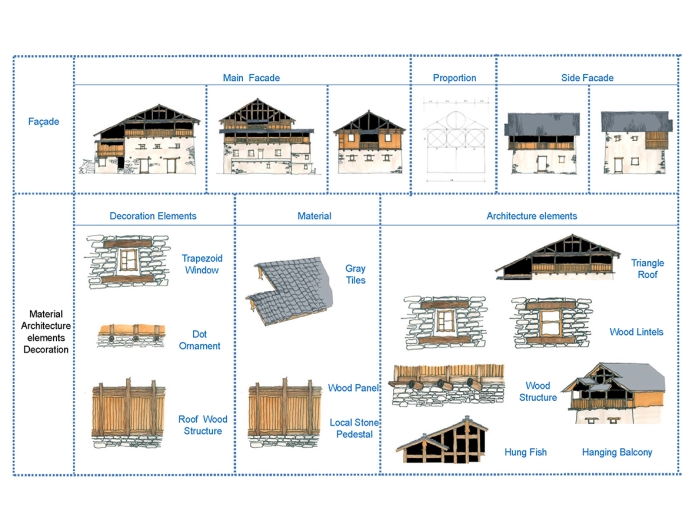

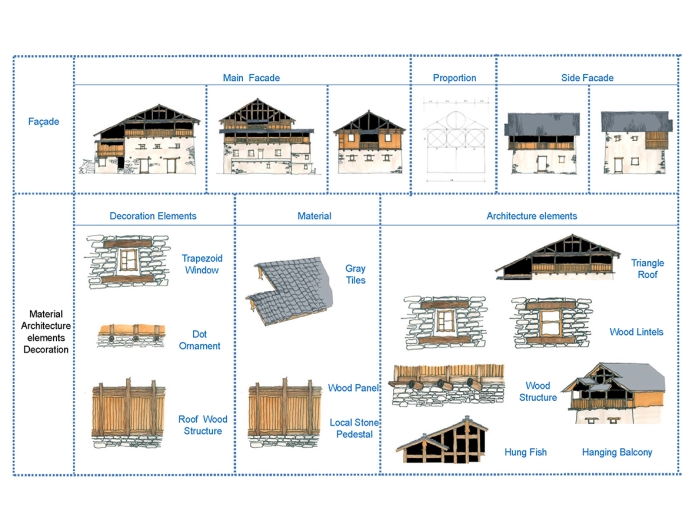

Fig.

12 - Typology of traditional Shenmulei house. Baoxing, Sichuan, China 2011.

Figg.

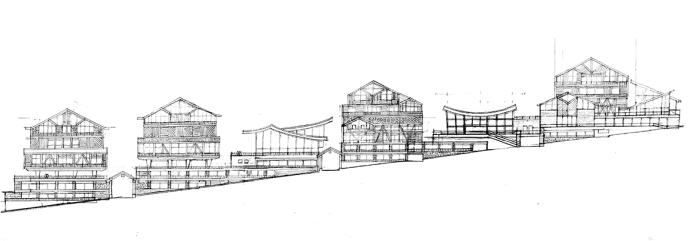

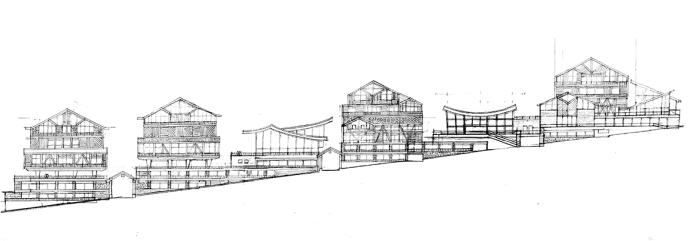

13-14 - Section sketch of guidelines for the master plan. Shenmulei, Baoxing, Sichuan, China 2014.

Fig.

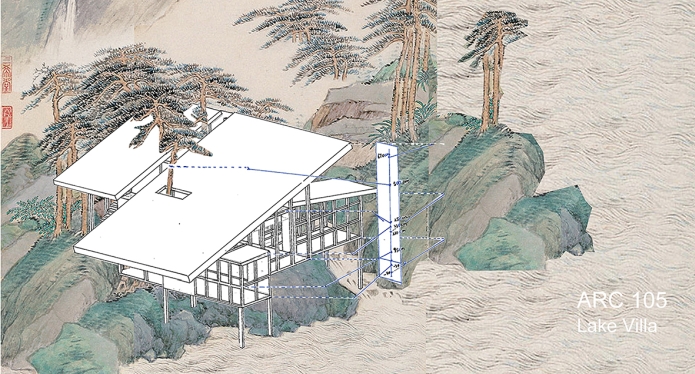

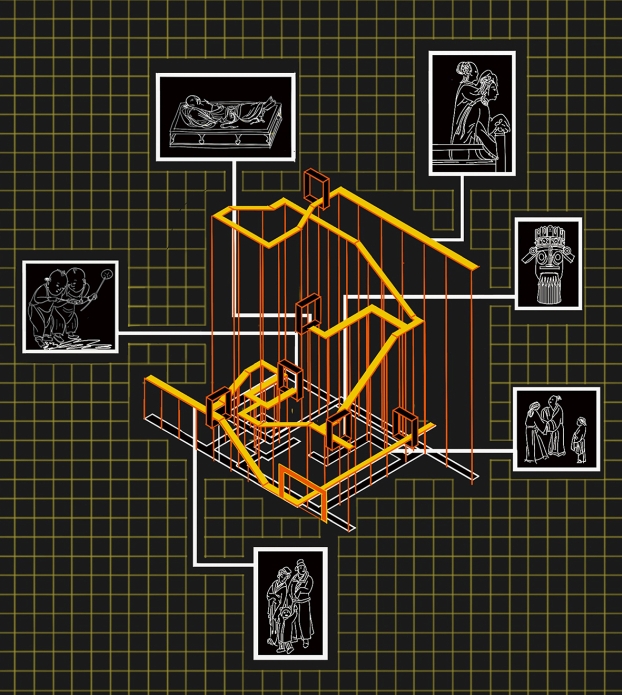

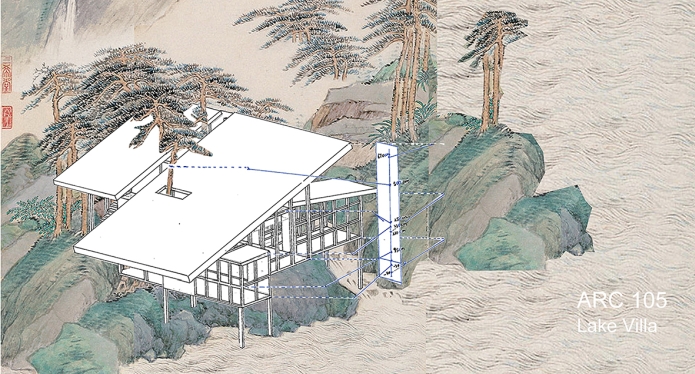

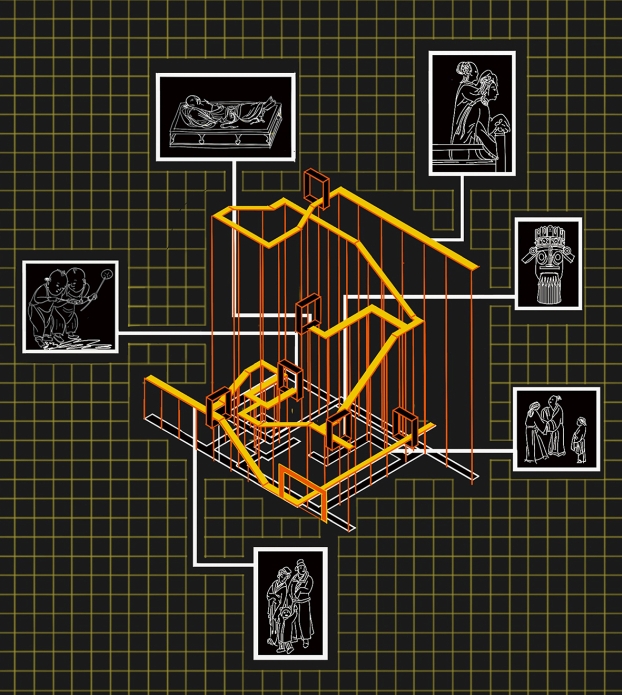

15 - Axonometric drawing of a villa placed in the painting context.

Hongyi Zeng, Design studio ARC105 AY 2018 at XJTLU, Suzhou, China.

Fig.

16 - Elevation, hand drawing. Hongyi Zeng, Design studio ARC105 AY 2018 at XJTLU, Suzhou, China.

Fig.

17 - Interior panorama, hand drawing. Hongyi Zeng, Design studio ARC105 AY 2018 at XJTLU, Suzhou, China.

Fig.

18 - Openings’ auspices related to the Lu Ban omens’ poems.

Meilun Zhang, Design studio ARC105 AY 2018 at XJTLU, Suzhou, China.

Fig.

19 - Openings’ auspices related to the Lu Ban omens’ poems.

Yifan Qian, Design studio ARC105 AY 2018 at XJTLU, Suzhou, China.

Fig.

20 - A survey using the Luban measurement system through the use of

symbols, student Xu Zhan, ARC105 Architectural Composition Course,

XJTLU, Suzhou, China 2019..

Fig.

21 - Copper imitation of the Luban ruler available online on Aliexpress.

Fig.

22 - A House for all seasons.

Fig.

23 - Façade Construction Phases, A House for all seasons.

Fig.

24 - Chinese traditional house.

Fig.

25 - Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat, photo by Pedro Pegenaute.

Fig.

26 - bird-eye view, Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat, photo by Pedro Pegenaute.

Fig.

27 - Courtyard, Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat, photo by Pedro Pegenaute.

Fig.

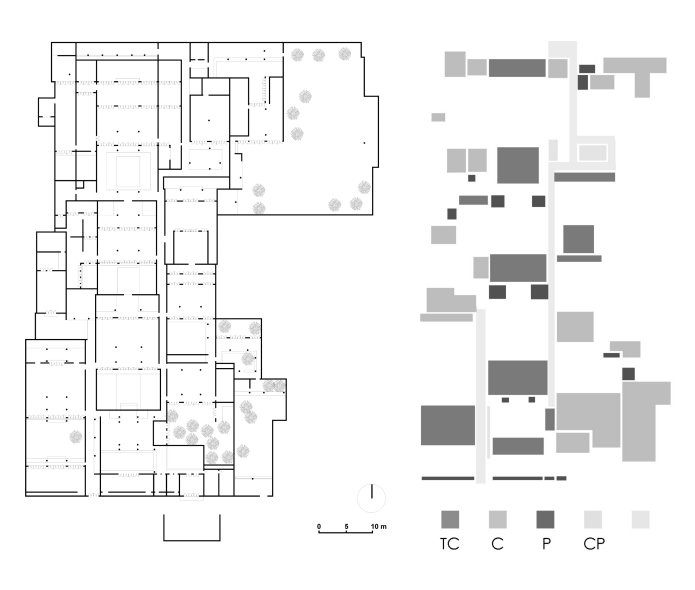

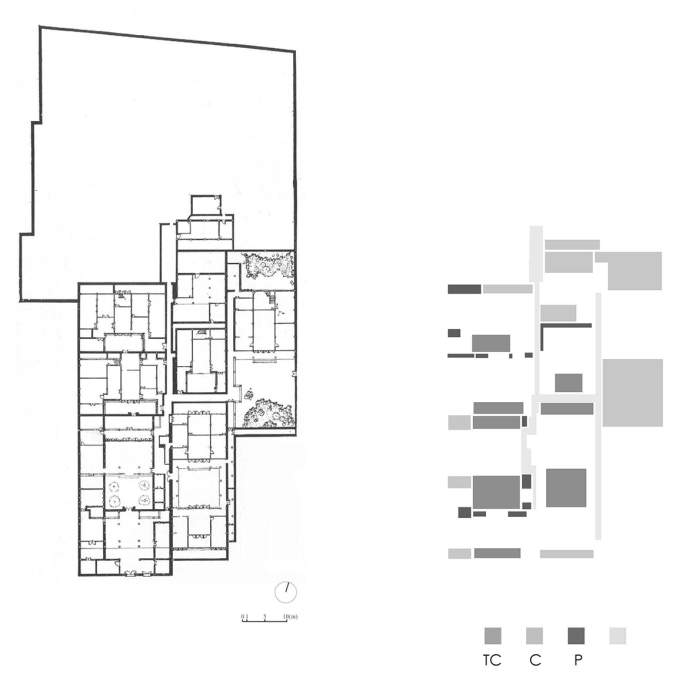

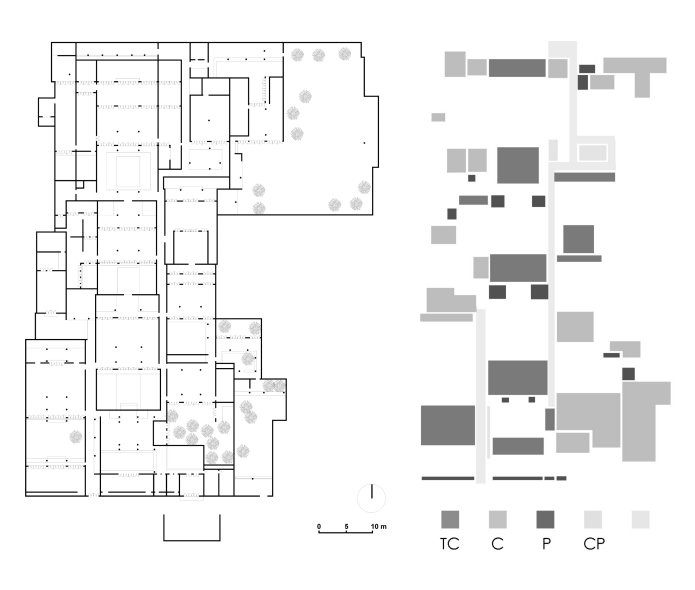

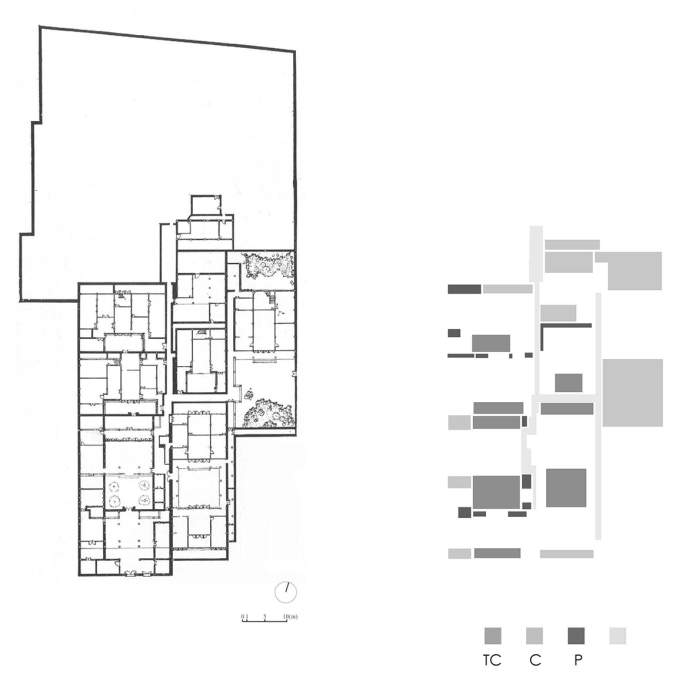

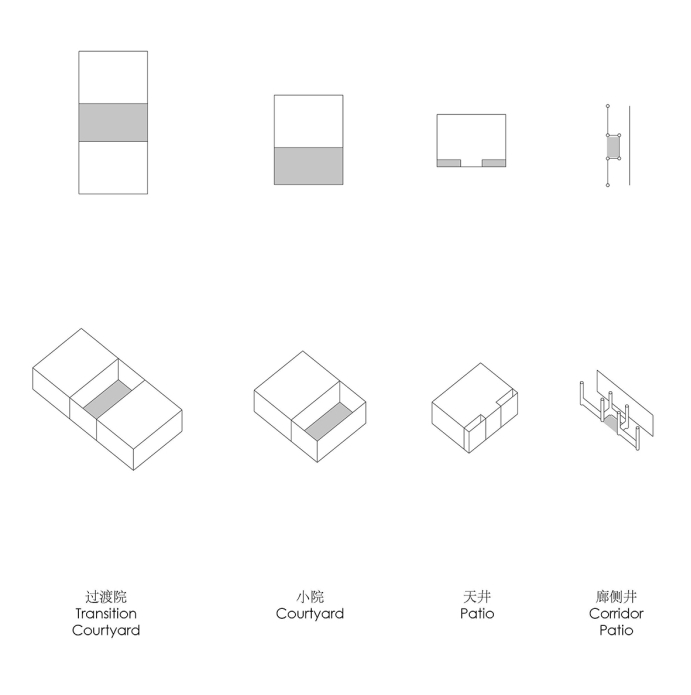

28 - Peng’s Residence in Shijia Alley, Suzhou, Nicola Pagnano and Ruqinq Lyu 2020.

Fig.

29 - Han’s residence in Dongbei street, Suzhou, Nicola Pagnano and Ruqinq Lyu 2020.

Fig.

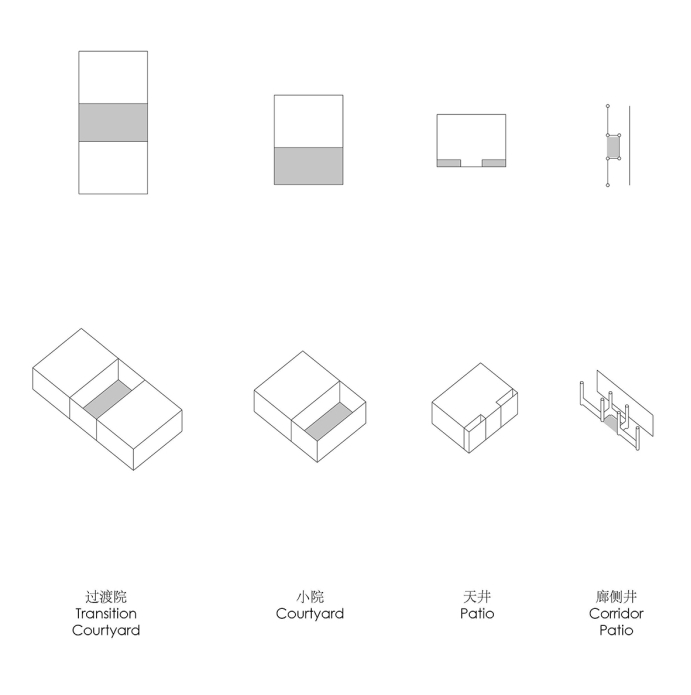

30 - System of courts in the residences of Suzhou, Nicola Pagnano and Ruqinq Lyu 2020.

In my 15 years of experience in China (from 2007 to 22) as an

architect first and then as a teacher (at Xi’an Jiaotong

Liverpool University), I have witnessed the development of new cultural

interests and aesthetic orientations in the architecture field. After

almost 40 years of architecture managed by prominent state-owned Design

Institutes, the professional activity of private architectural firms

began in China again in 1990.

The economic and technological progress of the last twenty

years

(2000-2020) has led to a change in architecture’s

constructive

and aesthetic processes. Young architects are amplifying a trend that

from 1950 to 1990 was very rare and carried on with discretion by a

small number of architects, namely an architecture with its own

identity that we could define as the beginning of modern Chinese

architecture. (Xue and Ding, 2018)

The evolution of the professional practice of

architects in

China over the last century: from Design Institute to private

architecture firm

British, American, and European architects dominated the

architecture market at the turn of the twentieth century, until the

arrival of the first generation of Chinese architects, who had just

finished their studies and training at the best American and European

institutions. At that time, architects in China start their studios

like Western countries as a modern profession. (Xue, 2006; Rowe Kuan,

2006)

Between 1949-1976 most foreign companies were confiscated or

nationalized. The Party gradually reduced the opportunity for private

architectural firms in the professional market. Most Chinese

architectural practitioners ceased their firms because they believed

that joining a state-own Design Institute would provide stable income,

secure their careers, and offer more opportunities in architectural

design. The Party and the state became both the project’s

clients

and the contractors, so the architectural professionals became state

employees. The design activities were seen as contributing to national

modernization and the public good rather than following the

architect’s interests (Hu 2009).

In November 1984, the Ministry of Construction approved for

the

first time the private small-scale architectural design firm Wang

Tianci.

The actual movement of private companies in the market started

with

Yung Ho Chang and his Atelier FCJZ in the 1990s. (Huang Yuan-Shao,

2010).

With the globalization of the world economy and

China’s

accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), China’s

industrial structure and economic system are undergoing significant

reforms, which have given architects and professional architectural

firms a vital opportunity. Starting from 2002, The government allowed

Foreign Invested firms to operate with local partners, and from 2006,

it allowed Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprise architecture firms (Long

Xiu).

In those years, however, the architecture was still managed by

the

Design Institutes and by foreign companies in partnership with local

partners. Small and medium-sized private studios that operated

independently and could focus on quality design were still few and

unable to exert any influence in the cultural context of architecture.

Experience in China

The experiences of my first two years in China made me

understand

that my approach to the projects and the language I used to describe

them did not entirely satisfy clients. In fact, they were not

particularly interested in the themes of Chinese identity and culture

or any case sensitive to social and environmental problems, but on the

contrary, they were looking for projects with a strong staggering

connotation, with concepts that are easy to understand and visualize: a

formalist architecture that was in fact what was proposed by most

Western architects. A trend that has not yet exhausted its course and

continues to produce atopic architecture that is utterly alien to the

context.

The classical architecture request by developers was a

commercial

strategy to sell to the new Chinese rich villas and palaces that

expressed a concept of wealth. Calling it classic is certainly not the

most applicable term, let’s say a patchwork of orders and

styles

that spans all centuries and types. For example, a Gothic church

enriched with Corinthian columns transformed into a villa. Traditional

Chinese architecture was associated with the popular buildings where

people of lower social classes lived who, although interpreted in a

contemporary key, did not express a status symbol adequate to the needs

of the new rich, inclined instead to demonstrate their wealth also

through architecture.

The many design experiences in which I had the opportunity to

participate are a demonstration of this difficult relationship, between

the memory of Chinese architecture and oblivion, the search for

internationalism and stereotypes of modernity.

One of the first design experiences I made in China was in a

great

site, the Inner Mongolia desert. I had to expand an existing resort and

re-design the facilities building.

The strategy adopted was to get knowledge of the physical and

cultural resources of the place; I started with a territory survey and

a visit to the surrounding villages to discover the spontaneous

architecture and meet the inhabitants to learn about the traditions of

the place. I asked the client for a hydrogeological map to identify the

aquifers, but I only managed to get an aerial photo of the area.

This image helped me visualize bands of vegetation that

started from

the lake and extended into the desert. I decided to design a

planimetric system along the arid strips not to touch the humid

vegetative bands. The designed buildings referred to traditional

architecture amplified by bioclimatic architecture devices.

Unfortunately, the client had little regard for the original buildings

because, according to their aesthetic standards, they were not suitable

for restoring an idea of an exclusive resort for wealthy tourists.

The result is a substantial atopic building surrounded by golf

courses near the lake, the worst thing that could be achieved in this

place both from an architectural and landscape point of view.

The metaphor

In 2012 I designed a resort in southwest China, in the

territory of

Yunnan, near the border with Thailand. This area is famous for

producing Pu Er tea, a particular type of fermented tea, among the most

expensive in the world. The project is located at the top of Bai Ma

Shan’s mountainous area (Mountain of the White Horse).

This time the project proposal originated from the reference

to the mythical origins of the founding of Chinese cities.

We began to explore the territory and study local

architecture. In

this area of China, the influence of Thai architecture is perceived,

especially in Buddhist temples. It was therefore decided to work on the

tectonics of local architecture, particularly of temples, interpreting

the complexity and heaviness of the roof as opposed to the lightness of

the walls. The first proposal consisted of drawing a section of one of

the resort’s units.

The section had the task of strongly restoring the

relationship

between the ground and the relationships among the inside and the

outside of the building. In addition, the section aided spatial

visualization, scale and aspect ratio.

This process was not used in Chinese studios where management

expects to see overall views, scenographic renders, and only later,

floor plans and drawings.

In 2014 I worked on a project for a strategic plan for tourism

development. I visited a project area at the border with Tibet,

Shenmulei, in the Chinese region of Sichuan, where an ethnic Tibetan

minority lives.

A water containment basin submerged the old town, and the new

town was rebuilt with a patchwork architecture of local styles.

When I arrived at the site, I visited the areas affected by

the

tourism development plan in search of local architecture. They were all

mountainous areas at 4000 meters. When the visit ended, I realized that

the regional architecture had disappeared. Most of the original

buildings had been submerged. However, during the territorial survey

phase, it was possible to identify a few traditional buildings halfway

up the mountains which were saved. A sectional drawing was drawn up

among the various documents we delivered to the client, which took up

the original types listed. The sketch depicted a street with shops,

restaurants, small hotel buildings and chalets. It was an attempt to

give guidelines for developing new facilities for tourism, oriented

towards an architecture that respects the characters and identity of

the place.

The spread of critical regionalism

If, on the one hand, these experiences demonstrate the

difficulties

encountered with the Chinese clients, on the other hand, there are

numerous testimonies of a changing process. The new generations of

architects who recently operated widely in the territory, sometimes in

remote places, pay greater attention to environmental values. They know

the importance of the Genius loci and the

relationship that

architecture should have with the physical and cultural context. The

large American and English formalist firms that dominated the market

since the Olympic games of Beijing are now placed side by side by small

Chinese, Italian, Spanish and French firms that helped change the

formalist trend with an architecture that respects local

cultures’ identity. The individualist gesture has been

replaced

by a sense of identity, social and ethical responsibility. The

beautiful form that seduces the great investor has been replaced by a

simple architecture based on community values and recognizability.

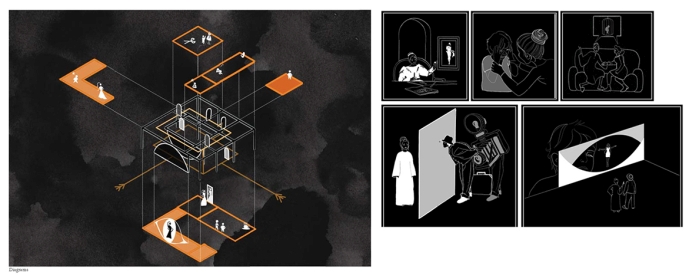

In this new course of Chinese architecture, architects measure

themselves against what can be considered traditional construction, in

which the theme of tectonics is a determining aspect. Another not very

well-known theme is the magic-propitiatory and auspicious aspect that

implies Chinese architecture in which measures, proportions and

specific tools regulated the construction of the building’s

tectonics. This a theme that, in some respects, could find a

correlation with the conceptual experiments of Bernard Tschumi in The

Manhattan Transcripts (1981) or with the musical proportions adopted by

masters of the Renaissance (Foscari-Tafuri 1983).

At Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University (XJTLU), I

was able to

directly experience the changes that characterize the new course of

Chinese architecture.

In the latter school and at the China Academy of Art in

Hangzhou,

teachers conduct research and experiment in design courses on the

themes of tectonics and critical regionalism.

With Adam Brillhart[1],

I

worked on a design process with second-year students that relates to

the tradition of carpentry. The design course, therefore, developed the

theme of tectonics and carpentry in its more traditional aspects, from

measurement systems to magical and propitiatory aspects.

The research involved a detailed investigation of the

measurement

tools used in the carpentry of the buildings built by Lu Ban, a famous

Chinese carpenter, engineer, philosopher, and inventor. He lived

between 507 and 440 BC.

Brillhart explains in his research that many types of

measuring instruments were used in traditional carpentry[2].

These not only allowed control of the buildings’ forms and

the

elements that made them up but also reflected some characteristics of

the culture of living in Chinese civilization.

Lu Ban’s tools are the most famous among many

measuring

instruments in traditional Chinese carpentry culture. A commercial

version of one of his rulers can be purchased on Tao Bao, the Chinese

eBay.

There are three categories of tools associates with stages of

construction. The compass instrument, for finding the orientation of

the house and the position of the front door, the Gaochi ruler for the

ratio of the wooden frames and the Lu Ban ruler for determining the

size of doors and windows.

The compass instrument utilized for the orientation was based

on

omens related to the stars positions and some other seasonal phenomenon

connected with the Chinese calendar. The geomancy master instrument was

endowed with a magnetic needle that would indicate the south

orientation of the building.

The Gaochi ruler was 5 to 6 meters high and a few centimetres

wide;

using this was possible to measure and build on a 1:1 scale. The

measurements of the structural components were marked through symbols,

and the carpenter will employ the ruler during the process of cutting

and shaping the wooden elements. Subsequently, it was utilized to

indicate the height or width of each tectonic part during the

construction phase. The whole elevation ratio and measurements of a

building were compressed into a small surface of ten centimetres width

and six hundred centimetres high.

The dimensions were linked to poems that act as omens through

proportional ratios in the Lu Ban ruler. The carpenter attributes to

the openings a poem that will bring auspiciousness, luck, wealth, or

happiness to those who live there. The omen remains a secret guarded by

the carpenter and not revealed to the inhabitants of the house. The

whole construction process, even the drawings, calculations, and tools,

is kept secret by the master carpenter. The ruler was a personal tool

of great value that the carpenter jealously guarded.

Here the experimentation with students on the theme of

tectonics

starts from traditional instruments and events (auspices): this

approach has led to interesting results from the point of view of the

design experience.

The design course develops tectonics in its most traditional

aspects, from measurement systems to omens.

Students must build their tools for the spatial dimensioning

of

buildings, use the original poems of auspices, and translate them into

events to be conceptualized to shape the structure. The project site is

an ancient Chinese painting, inside which students define the location

of their architecture. They identify the interior relationships with

the landscape’s elements represented in the painting through

a

prospective sequence.

This approach should sensitize students’ architects

to the

importance of local culture to find principles or ideas for the project

and thus direct them towards a creative process that blends tradition

with the contemporary, favouring a propensity for tectonics rather than

self-referential formalism.

The Architecture of critic regionalism in China

Below are some recent examples of architecture in China, which

stand

out for the attention to the characters of the place and the

interpretation of traditional architecture, as well as an interview

with Yiping Dong. YD is an associate professor in the Department of

Architecture of Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University.

House for all seasons, John Lin, Shijia Village,

Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, 2012

Shijia Village is located in Shaanxi province, in northwestern

China.

Development in rural areas such as Shijia, typically abandons

traditional styles in favour of more generic housing types. This is

partly the result of the area’s gradual shift away from

economic

self-reliance: as labour tends to migrate toward more urbanized

centres, traditional collective self-construction is increasingly

rendered unviable. As a result, outside labor and materials have become

the driving force in defining the rural housing scene. Funded by the

Luke Him Sau Charitable Trust with support from the Shaanxi

Women’s Federation and The University of Hong Kong, this

project

looks at the idea of the village house vernacular and proposes a

contemporary prototype. By combining ideas from other regions of China

as well as traditional and innovative technologies, the design is a

model for the modern Chinese mud-brick courtyard house.

All the houses in the region around Shijia are constructed of

mud

brick and occupy land parcels of 10 meters by 30 meters. The design

promotes a sustainable alternative within this framework by integrating

rammed earth, biogas, rainwater storage, and reed bed cleansing systems.

Serving also as a centre for women’s handicrafts,

the Shijia

House bridges the individual and collective identity of the village.

Construction of the house has initiated a new phase for the local

economy, developing a new cooperative business in traditional straw

weaving. Overall, the project represents an architectural attempt to

consciously evolve rural house dynamics in China.

(from the project report, John Lin 2012).

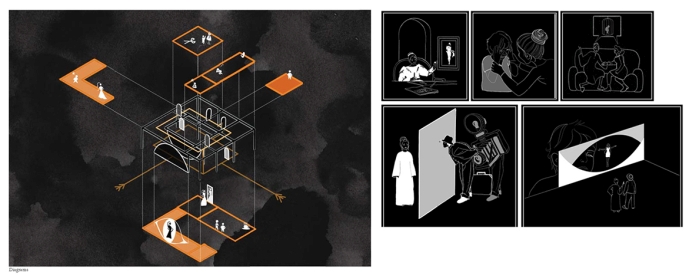

Neri&Hu Design and Research Office, The

Walled, Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat, Yangzhou, 2017.

Adaptive re-use of existing buildings and a new proposal for

20 rooms boutique hotel.

Neri & Hu’s project interprets the theme of

Suzhou

courtyard buildings and gardens, such as Han’s residence on

Dongbei road in Suzhou, Peng’s residence in Shiia Alley in

Suzhou

and Pan’s residence on Nanshizi road in Suzhou. In these

types,

the ‘served spaces and serving spaces’ can be read

through

the use of long service corridors that connect the rooms and a central

path that develops along a sequence of courtyards and rooms that

generally ends in a garden. This distinctive aspect of Suzhou noble

residences is revisited in a modern key by architects with offices in

Shanghai who manage to hold together different design themes such as

recovery and new construction, modernity and tradition. All of this is

through a rigorous planimetric system and a single complex which seems

perfectly in balance with the context.

Interview with Dr Yiping Dong[3]

Nicola Pagnano: Dear

Professor Dong, can you

describe the relationship between Chinese regional architecture and the

transition from the Drawing Institutes to the diffusion of small and

medium-sized architectural firms?

Yiping Dong: The great

transformation from the

economic point of view of the last twenty years also affects technology

and consequently the construction process of the enterprises.

Innovation in construction processes offers designers more technical

solutions that were previously limited.

Thanks to the openness of the world, it is possible to access

architectural information of the highest standards and consequently

raise the awareness of critical education through the media,

publishing, architecture exhibitions and open public competitions. The

combination of these events leads to a broader understanding of

architecture among young people, who have easier access to information,

and large real estate companies or other investors.

The public’s understanding of what is

“good”

architecture was very limited due to the lack of aesthetic education.

The large-scale Design Institutes paid fewer interests to competitive

design proposals, while most projects were commissioned until 2000.

Being a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) opened the door

for international design companies in the market of China.

I.M. Pei’s architecture has been an important

landmark in

interpreting modern Chinese architecture; think of the Fragrant Hill

Hotel built in 1982 in Beijing and the most recent museum in Suzhou

constructed in 2006. However, between 1950 and 1990 were built,

fascinating examples of modern Chinese architecture not attributable to

a single architectural style.

These rarities testify to the presence of an elite of

architects who

have never stopped creating buildings with an aesthetic value and a

particular identity. An example of this is the Peace Hotel in Beijing

(Heping Hotel), arch. Yang Tingbao, 1953. The Baiyun Estate, 1962, and

the Double Creeks Villas, 1963 were both realized in Guangzhou and led

by Mo Bozhi for the Guangzhou Architecture Design Institute. These two

projects combined the regional garden feature in South China with the

modern architectural spatial approach.

Architecture with a character was not always accepted or well

regarded by the institutions, and today many of these buildings are

almost unknown. Perhaps these few realizations are the seeds of

architecture that reflect the sense of belonging spreading among the

new architects in recent years.

When Design Institutes changed their form from state own to

independent companies, they hired foreign and young Chinese architects.

This process raised the quality of the projects in the consistent

production of architectural artefacts.

In addition, the media supported the new trend by showing

examples

of architecture with aesthetic value through television programs, a

guide for public opinion.

NP: I remember that the

Wang Shu Pritzker Prize

victory in 2012 was a special moment for the architects working in

Shanghai. I think that the prize reveals to the world the existence of

a modern Chinese style.

Well-known architects and studios in China that

believe in

regional architecture were finally recognized in China and abroad.

Consequently, many new studios of young architects have begun to

propose architecture with a strong identity imprint, which respects the

characters and culture of the place.

YD: Yes, he was very influential

in the

professional and academic world, conferences, and television programs

and even the students wanted to know more about Wang Shu’s

architecture and understand the motivations that led a regionalism

architecture to win the Pritzker Prize. The impact was significant, and

some governments were looking to carry out similar projects in that

region. But the social conscience is not yet mature for understanding

the importance of embodying the culture of a place in the architecture

design; most administrators are looking for a famous architect, more

than a style representative of local culture. Critical regionalism,

more than architecture with aesthetic values that can be traced back to

artistic values, is considered practical architecture that belongs to

constructions tectonic. In addition, there are emerging exhibitions

that are still inside a relatively professional community instead of

the general audience. Wang Shu is best known in the professional and

academic world. People outside of academia and architecture are not so

aware of the significance of his contribution. In Hangzhou, where Wang

Shu works, perhaps people do not know the architect’s name,

but

that type of architecture is now recognized as “good

architecture”.

Notes

[1]

Dr Adam Brillhart is an

Assistant Professor in the XJTLU Department of Architecture. In 2012 he

received a scholarship from the Chinese government and was Wang

Shu’s first non-Chinese PhD student at the China Academy of

Art.

[2]

See: Brillhart, Adam, Dong

Yiping, Zhang Yuyu. “Conservation Practice of the Wooden

Gaochi

Instrument, An Exploration in Architectural Tools and Design

Inheritance”. Xi’an Jiatong-Liverpool University

SURF.

Jul-Aug-2021.

[3]

Dr Adam Brillhart is an

Assistant Professor in the XJTLU Department of Architecture. In 2012 he

received a scholarship from the Chinese government and was Wang

Shu’s first non-Chinese PhD student at the China Academy of

Art.

References

FOSCARI A e TAFURI M. (1983) – L’armonia

e i conflitti. Einaudi, Turin.

GREGOTTI V. (2014) – Il territorio

dell’architettura. Feltrinelli, Milan.

HAN JIAWEN (2017) – China’s

architecture in a globalizing world: between socialism and the market.

Routledge, New York.

HU XIAO (2009) – Reorienting the

profession: Chinese architectural transformation between 1949 and 1959.

ETD collection for University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AAI3359467.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dissertations/AAI3359467

LEFAIVRE L. e TZONIS A. (2003) – Critical

Regionalism: Architecture and Identity in a Globalized World. Prestel,

New York, London

ROWE G. P., KUAN S. (2002) – Architectural

Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China. The MIT

Press, Cambridge, London.

XUE CHARLIE Q. L. (2006) – Building a

Revolution: Chinese Architecture since 1980. Hong Kong

University Press, Hong Kong.

XUE CHARLIE Q. L. (2018) – History of

Design Institutes in China: From Mao to Market. Routledge,

New York.