Athens 1933.

A new theatre in the urban scenario

Luisa Ferro

Fig.

1 - Distribution of refugee settlements in the metropolitan area of

Athens and Piraeus, post 1922.

Fig.

2 - Athens 1933 plan, re-elaboration by L. Ferro.

Fig.

3 - L. Ferro, Ridisegno della planimetria di Atene.

The

Patision-Alexandras Avenue crossroads is highlighted in the state plan.

The first (north-south) connects the large archaeological area, the

geometric figure of the neoclassical city, the quadrilateral of the

Athens Polytechnic with the new neighbourhoods to the north. The second

(west-east) the rationalist neighbourhood for refugees (fig. 6) with

the self-built neighbourhood of Ambelokipi, in which the school

designed by Mitzàkis is located (fig. 7). In the centre of

the crossroads is the theatre of Pikionis. (Elaboration L. Ferro)

Fig.

4 - Photo taken in 1933 by the painter N. Hatsikyriakos-Ghykas during a

study visit to the self-built refugee settlements.

(Hatsikyriakos-Ghykas Archive, Benaki Museum).

Fig.

5 - Photo taken in 1933 by the painter N. Hatsikyriakos-Ghykas during a

study visit to the self-built refugee settlements.

(Hatsikyriakos-Ghykas Archive, Benaki Museum).

Fig.

6 - In-line buildings for refugee flat blocks on Alexandras Avenue,

1933-35 (architects K. Lascaris and D. Kyriakos).

Fig.

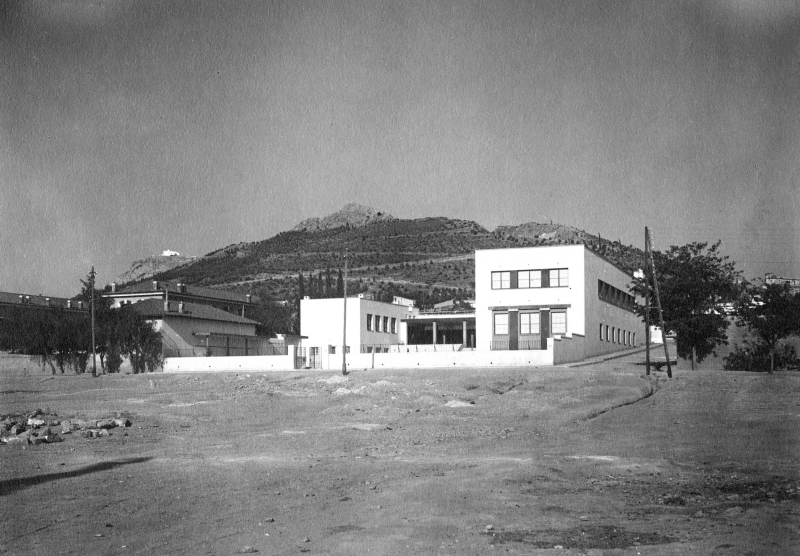

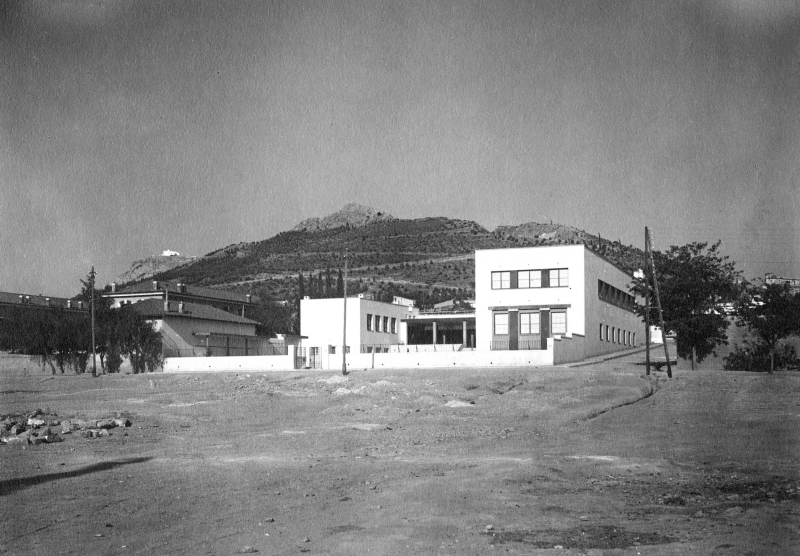

7 - Nikos Mitzàkis, Liceo ad Ambelokipi, 1930-32, ora

parzialmente demolito (Archivio di Architettura neoellenica, Museo

Benaki).

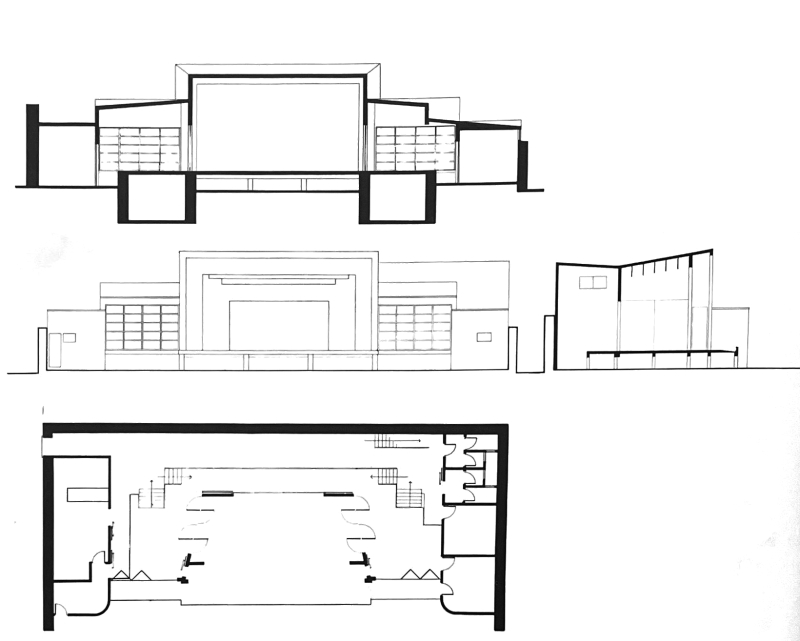

Fig.

8 - G. G. Steris, The Theatre M. Kotopouli by D. Pikionis, 1933 (D.

Pikionis Collection, Archives of Neo-Hellenic Architecture, Benaki

Museum).

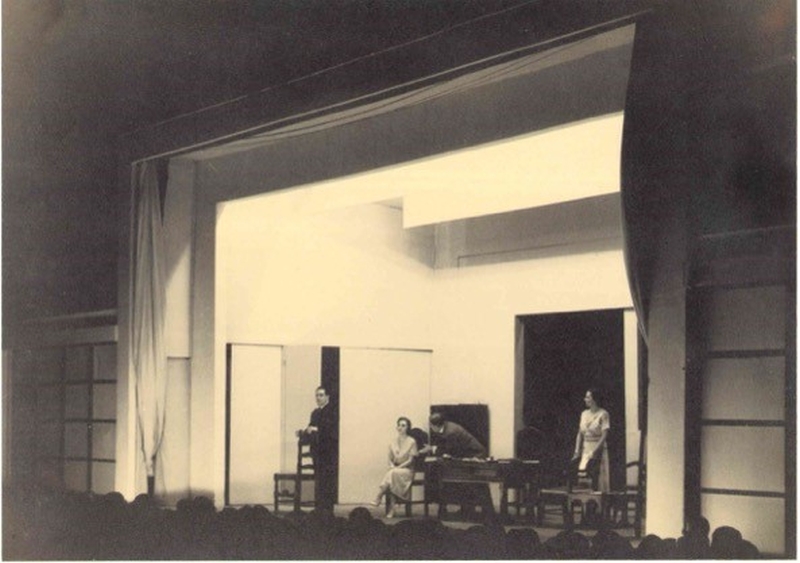

Fig.

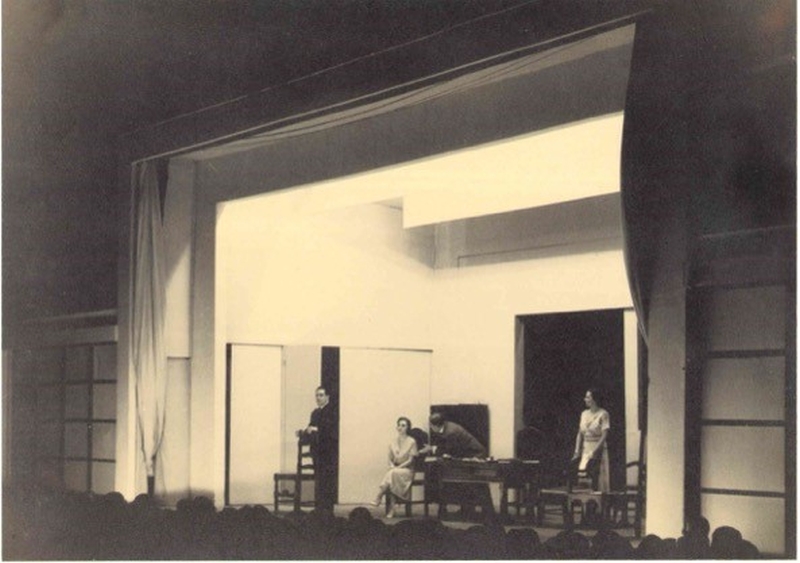

9 - D. Pikionis, Teatro Marika Kotopouli, 1933 (Fondo D. Pikionis,

Archivio di architettura Neoellenica, Museo Benaki).

Fig.

9 - Dimitris Pikionis, Theatre Marika Kotopouli, 1933 (D. Pikionis

Collection, Archives of Neo-Hellenic Architecture, Benaki Museum).

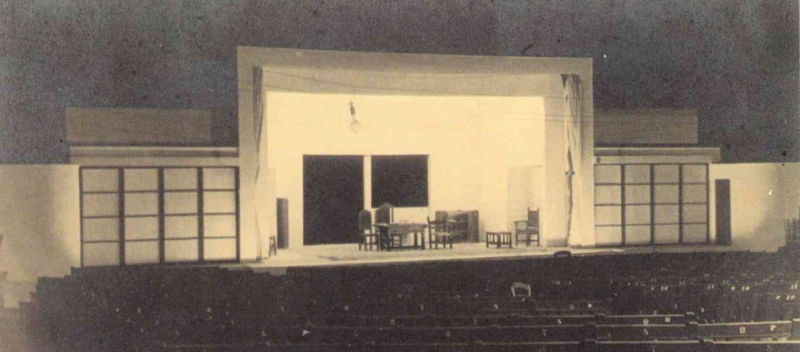

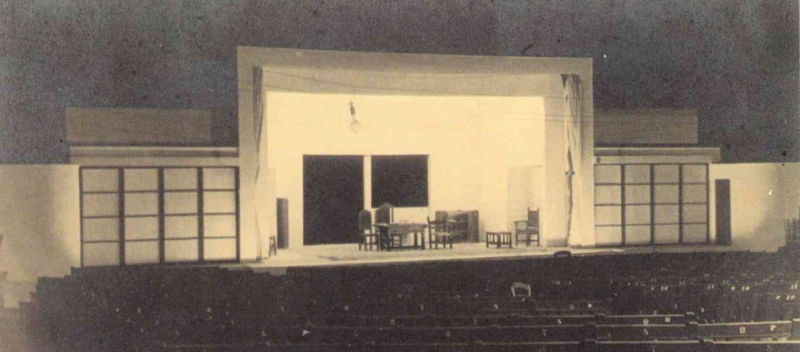

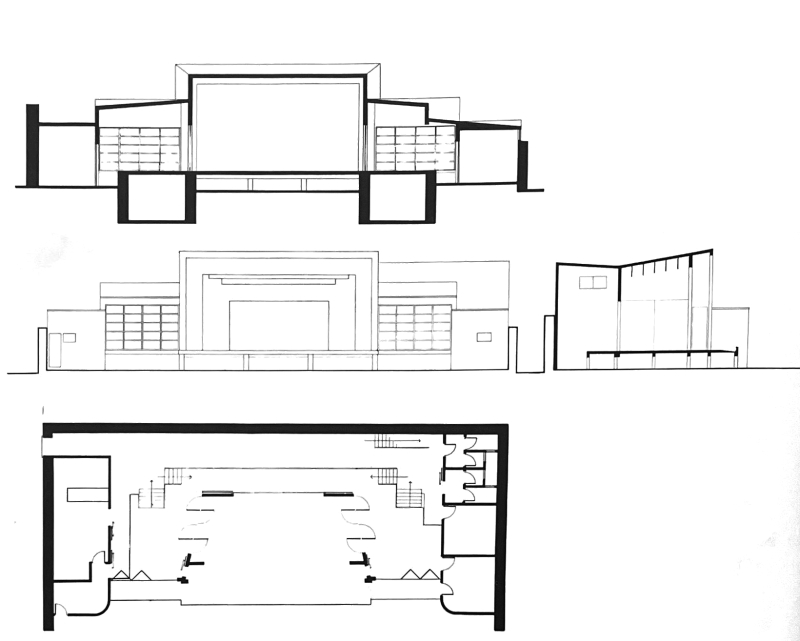

Fig.

11 - Dimitris Pikionis, Theatre Marika Kotopouli, 1933 (D. Pikionis

Collection, Archives of Neo-Hellenic Architecture, Benaki Museum).

Fig.

12 - Dimitris Pikionis, Theatre Marika Kotopouli, 1933 (D. Pikionis

Collection, Archives of Neo-Hellenic Architecture, Benaki Museum).

We have a theatre now: an open-air theatre, fully equipped,

modern and built on up-to-date principles and concepts hitherto unknown

in the Greek theatrical world. […] On the corner of Heyden

Street and Mavromataion Street - which is the first street on the

right-hand corner of Patision Street after Alexandras Avenue and on the

corner of the Field of Mars, a cool and quiet corner - in less than a

month a veritable new world has been created (Kotopouli 1933).

The placement of the theatre is not accidental, it is a well-placed

move in the Athens under construction. After all, theatres have always

been a significant presence in cities, both symbolically and

physically. Place (location) is a constitutive element of theatre

identity. What is more, if we think that throughout history we find the

theatre, not always figured in a building, also in fairs, markets,

farmyards, and in the gathering spaces of a community. Thus, along with

theatres as clearly identifiable architectural places, it is the very

organization of urban space itself that very often acts as the

background of representations. In other words, the relationship between

the theatre space as a place of performance and its surroundings is

always dialectical and multiform, and above all never too neutral. Only

recently has the term “environmental theatres” been coined,

built in poor or transitory spaces, often in out-of-the-way

neighborhoods. This is research theatre (which had already begun with

the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century) conceived in close

relation to the surrounding context (Brook 1968, Cruciani 2005).

Urban Scene

Modern Athens, that of Nivasio Dolcemare, in Alberto Savinio’s

stories, was a village. A city reduced to its essentials, where the

traditional contrast between town and country was stripped of meaning:

it was no surprise to see herds of transhumant goats from the

Pentelicus pushing their way into the centre. The crucial date is

undoubtedly 1922 (the Asia Minor catastrophe, the genocide against the

population of Pontos and the forced population exchange), when things

changed drastically: the mass arrival of refugees completely subverted

the urban policy implemented until then. (Clogg 1996) In the face of

this enormous drama, it was not known what values to express for the

urban landscape. The city adopted the idea of a break with the nearest

past: modernism became a sign of optimism and prosperity and left a

legacy so wide-ranging that it had no parallel in Europe. The

orientation of architectural thought definitively degrades the role of

typological invention in housing policy. For the people of the shacks

(the poor and refugees), the price for a more humane life is the

apartment block, which spreads impressively according to the logic of

the market economy, the engine of promised prosperity. This process is

either self-perpetuating and transcends any urban planning programme.

Not only that, but the cultural role and architectural direction of

Modern Movement architecture is replaced by a current 'modernist'

style, which becomes the most widespread in post-war Greece, even more

so than the neoclassical style.

While the latter, starting from the monumental models of official

architecture, becomes in minor construction an expression of continuity

with the popular typological tradition, with the modernist style not

only is a disconnect created with the principles of cultured and

refined rationalism, which sought mediation with history, but all

cultural reference with the heritage of tradition is erased. Current

construction tends towards an international style and becomes a model

for master builders and constructors, leading to the complete negation

of the past in the name of modernization. Alongside master plans that

were never truly realized, the vast and unplanned extension of the city

advances (Christofellis 1987; Filippidis 1999; Giacoumacatos 1999;

Ferro 2004).

But let us go in order. Let us begin with the numbers that reveal

the extent of the wave of refugees arriving in a short period and

settling in the areas of Athens and Piraeus: the population increased

by 30.6 per cent, according to the 1928 census data. In Athens,

refugees represented a quarter of the population, in Piraeus a third.

Thus the already existing housing crisis increased enormously. In 1928,

244,929 refugees settled in the Athens metropolitan area; new

expansions required the mobilization of multiple institutions and funds.

The main actors in charge of providing solutions to this colossal

humanitarian crisis and organizing its spatial footprint were the Greek

state and foreign charitable organizations such as the Red Cross and

the Near East Foundation. Initially, the situation was perceived as

temporary, so the refugees were housed in public buildings or in

private buildings occupied or requisitioned for this purpose. The great

need for immediate accommodation led to the creation of temporary

slum-like structures in open spaces in and around the urban fabric.

Later, having accepted the permanence of the situation, a series of

legislative measures attempted to solve the housing problem by creating

planned settlements.

Several institutional bodies were founded at that time: the Refugee

Assistance Fund (in Greek TPP, born in 1922), later replaced by the

Refugee Settlement Commission (in Greek EAP, 1923-1930), financed by

the League of Nations in the form of an international loan. The EAP was

supposed to act autonomously, without the involvement of the government

or any administrative authority. However, the Ministry of Welfare,

which was already involved in settlement construction, took over the

work of the EAP after the land under its jurisdiction had been used

(Kairou, Kremos 1983-84, Mandouvalou 1988, Hirschon 1989).

In a first phase, TPP (later PAE and Ministry of Welfare) builds new

settlements in peripheral areas, creating new housing or restoring

existing properties, or giving land, building permits, subsidies and

technical assistance. But a second phase, almost parallel to the first,

soon takes place: landowners subdivide their land by selling it to

refugees, to build neighborhoods near organized settlements or wherever

they find space, creating new self-built settlements. The settlements

have an investment character, not a charitable one. Refugees have

contracts for houses in the form of a mortgage, paying the rates and

the rest with interest. The location of refugee settlements in some

cases exploits the proximity to industrial-manufacturing facilities. In

other cases, the process is reversed. However, the main declared

objective is that the settlements should be as invisible and socially

isolated as possible. Social segregation is accentuated in the spatial

layout of the capital with the creation of purely working-class and

popular communities: «they must not disturb the normal life of

Athens»[1].

As the city grew over the following decades, these satellite

settlements became part of the city, the previously uninhabited areas

between Athens and Piraeus were completely occupied and the two cities,

which had always been two autonomous entities even morphologically,

formed a single urban complex.

The urban plans of the settlements reflect a complicated and heated

architectural debate, sometimes applying the principles and standards

of modernist architecture (a grid system of parallel and perpendicular

streets forming blocks of buildings of the same size) and sometimes

those of garden cities (circular streets and symmetrical squares): the

shacks are organized in rows and some empty spaces are left for

communal spaces such as bathrooms, toilets, laundries.

The temporary housing units provided by the OPT and the EAP are:

single-family wooden houses, known as “Germanika”, as

compensation for the First World War; one- or two-storey houses, single

or double; two-storey houses with external stairs, arranged on square

plots around a common area; two-storey houses that each housed two

families; a one-storey house with a single room and a kitchenette

(about 32sqm per family) with a shared bathroom. (Vassiliou 1936)

In Athens and Piraeus, 56 neighborhoods are formed around the 19th

century city, forming a belt of new buildings. The first

“prototype” neighborhoods are born, such as those of Nea

Smyrna, Nea Philadelphia, Nea Gallipoli. Then there are suburbs built

as garden cities for middle-class social strata (Psichikó,

Filothei...). However, there are very few council houses compared to

the need. Thus, a large percentage of the refugees found accommodation

in self-built shacks in spaces granted by the state.

Between 1928 and 1932 (Venizelos government) a more organized

housing policy was set up. In the 1930s, the use of multi-storey

dwellings of which the typical dwelling is about 40 square meters,

according to modernist minimum dwelling standards, became increasingly

common. These blocks of flats are built to replace temporary housing.

The type of one-room houses, which can be joined under favorable

conditions, follows in detail the standard applied in the Frankfurt

municipality’s programmes «for the poorest of the

poor». The same standard is applied for two- and four-storey

houses, again designed according to German examples (famous are those

of Ernst May and Walter Gropius).

In spite of the state’s settlement law, some even very

innovative standards are often not respected. In some cases, attempts

are made to ease critical social situations through the cheap sale of

building land. Thus the most widespread type of housing remains that of

minimal dwellings (one or two rooms) made of wood, stone or brick with

rammed-earth floors, built on expropriated land and parceled out in

square blocks bounded by an orthogonal road network (Kandilis, Maloutas

2017, Filippidis 1999).

In this context, the architectural debate between the wars (of the

20th century) in the capital became complex, contradictory and full of

ideological conflicts, and episodically found a way to develop,

particularly in the construction of key architectural sites for the new

neighborhoods: open spaces and collective spaces, schools. Emblematic

is the case of school construction, which became an important testing

ground for modern architecture in Greece and which affected not only

the centre, but above all the suburbs, the refugee quarters and the old

suburbs. The school, often built in the middle of undeveloped farmland,

proves to be the only reference for a different (cultural and urban)

use of the city and for future development. The open spaces of school

buildings will become public squares and places for sports in the newly

built neighborhoods. (Giacoumacatos 1985, 1999)[2].

A common theme in the architectural debate is continuity with tradition,

its formal codification in contemporaneity. Thus, at a time when

architectural culture strives to assimilate the main international

currents, at the same time, in Greece, a movement of resistance to

cultural imports develops, giving rise to exceptional works that are

revolutionary manifestations of art capable of opening a complex

dialogue with Greek regionalism. In this sense, the modern transcends

those limits that had hitherto been ascribed to it to develop in

multiple directions.

Adding to the complexity of the debate is Dimitris Pikionis, a

(sometimes uncomfortable) protagonist on the architectural scene. The

intellectual battle (individual and collective [3])

of Pikionis gives concrete answers to the uncontrolled reconstruction

taking place (in Athens in particular), to the savage destruction of

the architecture of tradition. The concept of modernity becomes

increasingly subtle and elaborate, as a critical reflection of the

legacy of the past (Ferlenga 1999, Ferro 2004).

Pikionis takes a critical viewpoint by using the concept of

tradition to highlight the dehumanisation of the contemporary

environment. The Greek idiom is a tragic voice, the spirit of dissent,

a kind of “light substance” (Elitis 2005), a true category

of the spirit for interpreting reality. This “Greekness”

has vital roots in the ancient world, going back in time (Yannopoulos

1909, Pikionis 1927, Psomopoulos 1993). And the refugees are not

“other” than the Greeks are part of it. Figures, types,

forms of houses, of life, of art, everything must express the one

origin. Pikionis reverses the trend on the figuration of the house,

identifies the characters of that light matter, that 'red thread',

which gives continuity to the architecture of the Greek tradition

(including that of Asia Minor) from the typologies of antiquity to the

forms of contemporary spontaneous dwellings (Pikionis 1927). The Greeks

were up to Asia Minor now in the suburbs of Athens in barracks.

The meaning of tradition has a very broad scope. Tradition is not a

heritage that can be easily inherited; those who want to take

possession of it must conquer it with great effort. Art does not

improve but is in constant motion. Places must be studied in their

formal values, in their configuration, in their topography, as a

spiritual value for the mental associations they can evoke mythical and

archaic images that give meaning to things.

«The architect’s work is not to invent ephemeral forms,

but to revise the eternal figures of tradition in the form determined

by the conditions of the present» (Pikionis 1925, 1927, 1950-51).

The aim was on the one hand to preserve popular art that was falling

into oblivion and on the other hand to hand down memory in contemporary

design. «We must not lower us in the direction of vernacular art,

in search of the picturesque or genre fascination, but in order to

search for leaven to make our work grow» (Pikionis 1927, 1950-51).

To ignore the rhythm of the landscape, Pikionis often writes, the

demands of life in the name of functionalist slogans is to become an

uncritical importer of a culture that demands, on the contrary, to be

utilized and transformed by imagination.

In opposition to modernist slogans, he proposes formal principles

that enshrine poeticism in minimal spaces, which is not a question of

square footage but of variation of type, of working on the autonomy of

the pieces of the composition, on the volumes and levels that shape the

terrain[4].

To the standard he opposes the theme of diversification of the universal type:

Infinite are the variations that can thus be applied to the

basic form. And the line mysteriously takes you now towards the

ancient, now towards the medieval, now towards the primitive, now

towards a popular neo-classicism. And it is up to you, if you know the

mysterious language of form, to express that particular form that would

be the symbol both of the deepest essence of your tradition and of the

time in which you live. (Pikionis 1925, 1927, 1950-51; Psomopoulos

1993; Ferro 2002, 2004)

Thus, the concept of modernity becomes ever more subtle and elaborate

as a critical reflection of the legacy of the past. Conveying the true

meaning of the spaces of the home is the task of architecture, that is,

to express the poetry of everyday life» and to help the

Greeks remember that kind of identity of thought in which even refugees

can recognize themselves.

So he studies the refugee villages with their self-built houses,

drawing from them a kind of substantial form of human habitation, which

basically tells us how cities came into being. He also takes into

account that many of them had indeed become poor, but they were

cultured, well-educated people. «Even in the poorest houses

made of old planks and pieces of tin and tar paper, one could find the

golden section of Pythagoras. ... We then gained exceptional

experiences from our contact with space, a space that confused us, that

was neither indoor nor outdoor» (Hatzikyriakos-Ghykas 1934).

The Theatre

As mentioned in the opening, the location of the new Pikionis Theatre

in the city has a very specific meaning. It is located at the

crossroads of an important crossroads, the matrix of the future city.

The perpendicular axes could have constituted in turn itineraries

studded with important urban facts of modernity, specialized places,

collective spaces for the city.

Mavromataion Street, runs parallel to Patission (28th October Avenue,

the street of the Athens Polytechnic, the Archaeological Museum and the

Academy of Art) and with it defines a narrow strip of blocks that come

to rest on the Field of Mars, the great green area of the 1920s master

plan. Patission was born from the geometry of the neoclassical plan of

the new capital city, the work of genetic engineering, which reshaped

the forma urbis and compacted itself in the mesh of the triangle

Sintagma, Omonia, Ceramico (Mandouvalou 1988). It is the matrix of an

orthogonal (almost Hippodamian) development linking the ancient city

towards the peripheral districts to the north. The design begins with

the first expansions (1864- 1909). The master plan (1920-25 Kalligas,

Hébrard) draws, following the figure of the orthogonal

chessboard, the avenue Alexandras (north of Mount Lycabettus). The axis

connects Patission with the new neighborhoods to the east, that is

Ambelokipi. The planned design of the crossroads is at odds with the

rest of the city, which proceeds haphazardly and without coordination

(Biris 1966, Filippidis 1999).

Along these axes a number of important architectural landmarks: among

them the blocks of houses in a line, the houses for the 'poorest of the

poor', shreds of the rationalist city arranged perpendicularly on

Alexandras Avenue and facing the green area of the Field of Mars, the

Mitzakis school in Ambelokipi immersed in the urban scene of the

self-built shacks of refugees. And so, in the centre of this important

carriage house, the new theatre was established in June 1933, to give

new perspectives of entertainment to the neighborhoods under

construction, opening up possible visual fields, even dramatic ones, in

the city.

A kind of anticipation of the Biris 1946 master plan (never fully

realised): Patision and Alexandras as the new crossroads of the

contemporary city. Alexandras connects Kolonos (ancient academy) with

Ambelokipi, Patision the large archaeological area, the design of the

capital city with the neighbourhoods to the north. New urban places,

city design and refugee neighbourhoods within a defined, geometric

urban design (Mandouvalou 1988, Filippidis 1999).

In Greece, experimentation with open-air theatres has had particular

important contributions.

Sikelianos, Eva Palmer, the painters Tsarouchis, Steris, Papalukas,

Hatzikyriakos-Ghykas contributed, in a way influenced, despite

Greece’s marginal position in the theatrical world, the

changes and experimentation on theatre architecture in the early 20th

century (Fessas-Hemmanouil 1999, Ferro 2004). It was a kind of return

to the theatrical tradition of ancient Greek culture and to certain

popular performing traditions, a kind of transmitter of Greek thinking,

a factor of identity even for those who came from the distant

territories of Asia Minor. It evokes a time when theatre is not in a

theatre, but on moving stage, chariots, raised platforms; spectators

standing or seated at tables, in front of a glass, taking part in the

action, replaying the actors; theatre done in backrooms, attics, barns;

one-night stands, a tattered sheet pinned to either end of the room,

battered panels concealing rapid changes. The problem is not whether a

building is beautiful or ugly which formal code it uses: the theatre

building must become an extraordinary meeting place or it remains

unresolved, cold, empty. This is the mystery of theatre and the

architecture of the small theatre in Pikionis encompasses this mystery.

It can be a puppet theatre, a shadow play or, as in this case,

classical and avant-garde performances (Brook 1968).

The theatre consists of the architecture of a stage set (designed as a

prototype) within an enclosure that, like the ancient Dionysian

theatre, is open to the city:

All around is a high wall with a promenade with a decorative

iron railing. A booth next to the entrance houses the ticket office,

while a small building in front of us as we cross the threshold

contains a large, comfortable bar. But there is nothing else inside the

new theatre, and even these few structures are simple, without any

particular decoration. Yet the simplicity is imbued with grace and an

aesthetic concept. (Kotopouli 1933)

There are no seats. Chairs (old chairs from the Attic Cinema) are

stacked in a corner and available. Or they can be brought from home.

«There will be 995 such seats in the stalls, with about two

hundred at the back, like a sort of gallery, and it will be possible to

place another 150 around the stage at each evening

performance» (Kotopouli 1933).

The important part of the new theatre (the only one) is its stage. And

it is this dimension that gives it its character, that makes it

different, that makes it a truly valuable acquisition for the Athens of

the time.

The stage building

is unusual, especially in that it is divided into three

parts, and is quite dissimilar to what we have so far called by this

name in Greek theatre. The Athenian scenic space originated from

imported models that, in turn, were connected to a basic concept

borrowed from painting: that is, the possibility of creating an

impression by suspending scenic backdrops and trying to obtain a

maximum of perspective. This concept ignored entirely the structure of

the building in which it sought to reproduce the desired impression.

However, modern developments in the theatre (Kandinskji for example:

light and color instead of scenes, or Gropius with his theatre) have

introduced the predominance of an architectural concept, i.e. they

aesthetically take care of the envelope and the stage by attempting to

achieve the atmosphere sought by the author with simple and clear

details, without making use of pictorial effects, but rather by using

space and a suitable adaptation of color, form, masses. (Pikionis 1958)

The new theatre will have walls on both sides, like walls,

which will enclose the stage and truly give it the form of a room, into

which the actors can only enter or leave through real doors. Thanks to

a special mechanism they can open in the middle and rotate to act as

wings. But in addition to the main stage, there are two smaller stages

at the sides, where scenes of secondary importance can be performed.

... When the curtains closing the central stage are open, the

three-part stage will form a single unit, with only two pillars to

remind us of the partitions. (Kotopouli 1933)

Pikionis quotes Japanese theatre as an example, understood not

as a kind of permanence of a universal original form. The architecture

of the stage space is a return to ancient theatre, even to that of the Mansiones, the

demountable rooms of medieval theatre. But above all it is a reference

to popular theatre, to the white cloth of the hut where the animator of

the Shadow Theatre moves: «The shadows of the Karaghiosis

theatre descend from the mysterious ancient cinema, from the play of

shadows projected on the wall of a cave, to which Plato compared our

memories» (Yourcenar 1989). The theatre will be demolished to

make room for new building lots.

IV Ciam

On the first of August, the steamship “Patris

II” of the Neptòs company arrived in Piraeus after

three days of sailing, with the hundred congress participants on board.

The great spectacle of the 4th International Congress of Modern

Architecture begins and the participants are completely unaware of the

Greek context and the ongoing architectural debate (Bottoni 1933; Ferro

2002, 2004). True, on this occasion the charter of the rational city is

drawn up, but it seems almost out of place: Athens was already going

further, in negative and in positive.

[…]

Difficilmente è possibile immaginare

una città contemporanea tanto degradata quanto Atene. Forse

in nessun altro campo si nota così tanto la mancanza di uno

spirito creativo capace e sapiente, di una volontà in grado

di contrastare le forze negative.

[...] It is hard to imagine a contemporary city as degraded

as Athens. Perhaps nowhere else is the lack of a capable and wise

creative spirit, of a will capable of counteracting negative forces, so

noticeable.

It is fair to say that awareness of this situation is a matter of

individual conscience and responsibility: it is natural and human - but

perhaps also necessary - to feel diminished, at least the most

sensitive of us, when confronted with the state of our city and the

ideal solutions, and the efforts of contemporary urban planning. [...]

This land is not just any land. Its spirituality is a supreme model,

insistently demanding to be applied by dominating and integrating all

other demands of functionalist architecture and urbanism. Of course, I

am not just talking about a physical place, but also a spiritual place.

Thus I find the operation that every artist must perform twofold:

1. bring his work back to the rhythm of the landscape; 2. submit it to

the sacred demands of life. The first operation requires a

harmonization of the potential of the spaces, volumes, forms and themes

of the work in relation to the dynamics of the light, the rhythm of the

landscape, the nature of the climate. [...] The second operation

presupposes acute psychological observation, a sensitivity capable of

registering and then giving form to the hidden virtualities of our

lives. [...]

This twofold operation has no rules. It is, as El Greco says for

painting: action, purely personal inspiration. Judging by the form the

new movement is taking in our country, I must say that this is the

operation we all need to perform, along with all the others, if we want

to be cultured operators rather than importers of civilization.

This alone will make us capable of critically reading the transitory

mottos of art, which for reasons of polemics and the need to define an

artistic movement (rationalism) limit it, excluding the potential of a

multitude of virtues, thus limiting the concept of Art.

It is necessary to reflect better on the solutions that the West offers

us, in order to avoid what is fast becoming true: the crystallization

of a new banality, the establishment of a new academicism. (Pikioins

1933)

The event of the Congress is well known, but what is important

to emphasise is a kind of “hidden” debate

concerning Greece and the concept of tradition. Anastasios

Orlandos’s speech during the 3 August ceremony at the

Polytechnic and Pikionis’s paper will give an unexpected

twist to the proceedings[5].

Notes

[1]

Updated studies have

recently been published, with an extensive bibliography: MYOFA N.,

STAVRIANAKIS S. (Harokopio University) 2019, Α

comparative study of refugees' housing of 1922 and 2016 in the

Metropolitan area of Athens https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336107098. e KLIMI M. (TU Delft Architecture and the Built Environment)

2022, The Housing Rehabilitation of the 1922 Asia Minor

refugees in Athens and Piraeus, http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:6f65e6dc-f33f-4a93-a357-453f904f3b43.

[2]

In 1930, Minister

Papandreou reformed the Technical Office of the Ministry of Education

by establishing a «Directorate of Architectural

Services».

Head of this office is Nikos Mitzàkis (1899-1941), whose

presence would become fundamental in the choice of architectural

direction and the cultural role of school construction in the city.

Among the design staff is the architect Patroklos Karantinos

(1903-1976, a pupil of Pikionis), one of the main advocates and

defenders of a modern architecture in Greece linked to the experiences

of European rationalism and a new strategy that manifests a critical

awareness of history but finds its roots in the building tradition of

the Greek islands.

[3]

«And then there were

the others: Kòndoglu, Papalukàs, and the

architect

Mitsàkis, Stratìs Doukas and Velmos; and then the

younger

generation: Ghikas, Tsarouchis, Engonopoulos, Diamantopoulos. How many

fruitful lessons were drawn from the context between these different

spirits, from the antitheses that each of them represented! I honestly

do not know what I could give them in return. But I am aware of what I

got from each of them» (Pikionis, Autobiography).

Pikionis is the protagonist of real intellectual battles. The

guiding principles of these battles also became a living part of

teaching. A large group of artists and architects, who called

themselves Omada Filon (group of friends), worked on them. With the

magazine “To Trito mati” (The Third Eye, 1935-37)

and other

events related to it (e.g. the 1938 exhibition on Greek Folk Art), he

clarified the research direction he intended to take with respect to

the Modern Movement.

[4]

In the early 1950s, with

the Exonì project and the magazine of the same name,

Pikionis

fine-tuned his way of thinking about living through a renewed idea of

the city. Exonì was a manifesto through which didactics,

experimentation and the theory of composition became a motif for

reflection, but also a philosophy of life. Every part of this small

settlement was designed for refugees and homeless people. On this

subject see FERRO L. (2014), Dimitris Pikionis e il villaggio

di

Exonì. La Casa Greca: mito dell’antico e

tradizione/

Dimitris Pikionis and the Village of Exonì. The

Greek House: the Myth and the Tradition, in Aa.Vv., Culture

mediterranee dell’abitare/Mediterranean housing cultures,

Clean, Napoli.

[5]

Le Corbusier himself, after

the congress, manifested a new line of research: modern spirit and

archaism, human scale and landscape became the new themes of his

architecture. The French architect was strongly influenced by his

second and last trip to Greece. In 1934, Christian Zervos, editor of

the magazine “Cahier d’art”, wrote a book

on

primitive art in Greece and published Panos Tzelepis’ article

on

the houses of the Greek archipelago. Le Corbusier’s article

La

ville radieuse dates back to 1935: «In 1933, the Congress of

Modern Architecture was held in Greece: we travelled around the

islands, the Cyclades. The deep, millenary life remains intact. We

discover eternal houses, living houses, of today, which rise from

history and have a section and a plan, which are precisely what we have

imagined for ten years. In this place of human measure, in Greece, in

these lands open to simplicity, to intimacy, to well-being, to the

rational still guided by the joy of living, the measures of the human

scale are present... ». The journey to the islands is also

documented in: HATZIKYRIAKOS-GHYKAS N., Some more memories

of Le Corbusier, in “Architecture in

Greece”, No. 21, 1987.

References

AA.VV. (1977) – The world of Karaghiozis,

vol. 2. Set, Emiris, Atene.

ELITIS O. (2005) – “La materia

leggera”. In: Id., La materia leggera. Pittura e

purezza nell’arte contemporanea, P.M. Minucci (a

cura di). Donzelli editore, Roma.

BIRIS KOSTAS H. (1966-1995) – Atene

dal

19mo al 20mo secolo. Melissa, Atene [Greek].

BOTTONI P. (1933) – Atene 1933.

Rassegna

di Architettura, 9.

BROOK P. (1968) – Lo spazio

vuoto,

ed.It. Bulzoni, Roma 1999.

CHRISTOFELLIS A. (1987) –

“L’epopea piccolo borghese

dell’architettura moderna”, trad. it. In: Aa.Vv.

(2012), Alessandro Chrisotfellis. L’opera e

l’insegnamento. Una lezione di architettura. Araba

Fenice, Cuneo.

CLOGG R. (1996) – Storia della

Grecia

moderna. Dall’impero bizantino a oggi. Bompiani,

Milano.

CRUCIANI F. (2005) – Lo spazio

del teatro.

Laterza, Roma.

FERLENGA A. (1999) – Dimitris

Pikionis

1887-1968. Electa, Milano.

FERRO L. (2002) –

“Technikà

Chronikà verso il regionalismo critico”.

L’Architettura cronache e storia, 560 (giugno).

FERRO L. (2002) – Ambivalenza

del moderno

in Grecia. Domus, 846 (marzo).

FERRO L. (2004) – In Grecia.

Archeologia,

architettura, paesaggio. Araba Fenice, Cuneo 2004.

FERRO L. (2004) – Arte e

architettura in

Grecia 1900-1960. Foro ellenico, rivista bimestrale a cura

dell’Ambasciata di Grecia in Italia, 59 (dicembre).

FERRO L. (2004) – Una Grecia

moderna.

L’Architettura cronache e storia, 590 (dicembre).

FESSAS- EMMANOUIL H. (1999) – Ancient

Drama on the modern Stage. The Contribution of Greek Set and Costume

Designers. Catalogo della Mostra omonima.

FILIPPIDIS D. (1999) – “Town

planning in

Greece”. In Aa.Vv., Greece. 20th Century

Architecture, S. Kondaratos (a cura di). DAM, Francoforte

sul Reno.

GEORGAKOPOULOU F. (2002) – Refugee

settlements in Athens and Piraeus. Encyclopedia of the

Hellenic World, Asia Minor [Greek].

GIACOUMACATOS A. e GODOLI E. (1985) –

L’architettura delle scuole e il razionalismo in Grecia. Modulo,

Firenze.

GIACOUMACATOS A. (1999) – “From

Conservatism to Populism, pausing at Modernism”. In: Aa.Vv., Greece.

20th Century Architecture, S. Kondaratos (a cura di). DAM,

Francoforte sul Reno.

GIACOUMACATOS A. (2003) – Gli

elementi

della nuova architettura greca. Pàtroklos

Karantinòs. Fondazione culturale della Banca di

Grecia, Atene [Greek].

HATZIKYRIAKOS-GHYKAS N. (1934) – Decorazione

(abbellimento). Simera 3, (marzo) 1934 [Greek], trad it D.

Casiraghi (Ferro 2004).

HATZIKYRIAKOS-GHYKAS N. (1934) – Decorazione

(abbellimento). Simera 3, (marzo) 1934 [Greek], trad it D.

Casiraghi (Ferro 2004).

HATZIKYRIAKOS-GHYKAS N. (1987) –

Ancora

alcuni ricordi di Le Corbusier. Architecture in Greece, 21

[Greek].

HIRSCHON R. (1989) – Heirs of

the Greek

Catastrophe: The Social Life of Asia Minor Refugees in Piraeus. Clarendon

Press, Oxford.

KAIROU A. e KREMOS P. (1983-84) – Atene

1920-1940: la ricostruzione di una capitale. Hinterland, 28.

KANDYLIS G. e MALOUTAS T. (2017) –

“From

laissez-faire to the camp: Immigration and the changing models of

affordable housing provision in Athens”. In:

E. Bargelli e T. Heitkamp (a cura di), New Developments in

Southern European Housing. Pisa, Pisa University Press.

KOLONAS V. (2003) –

“Architecture in

Greece”. In: C. Chatziosiph (a cura di), History of

Greece of the 20th Century: Interwar period

1922-1940, volume B2. Bibliorama, Athens, [Greek].

KOTOPOULI M. (1933) – Marika

Kotopouli ha

costruito un nuovo teatro all’aperto. La sua apparizione e il

repertorio, intervista. Ethnos [Greek].

MANDOUVALOU M. (1988) – “The

Urban

Planning of Athens (1830-1940)”. In: Sakelaropoulos

C. (eds) From the Acropolis of Athens to the port of Piraeus. Urban

Areas Regeneration Plans. Edition NTUA-Politecnico di Milano

[Italian+Greek].

MITZAKIS N. (1935) –

“Autobiografia”. In: C.A. Panoussakis (1999),

Nikolaos Mitzàkis (1899-1941). Prova

di una monografia. Museo Benaki, Atene [Greek].

MOUTSOPOULOS N. (1989) –

“Ricordi della

vita al Politecnico all’epoca di Pikionis”. In:

Aa.Vv., Pubblicazione in occasione del centenario della

nascita. (curatori vari). Politecnico di Atene, Atene

[Greek].

PAPAGEORGIOU-VENETAS A. (2010) – The

Athenian Walk and the Historic Site of Athens. Kapon

Editions, Athens.

PIKIONIS D. (1987) – Keimena,

A. Pikionis e M. Patousis M. (a cura di). Cassa di Risparmio Ellenica,

[Greek]; (1925), La nostra arte popolare e noi, in

“Filikì Eteria”, n. 3, 1925, trad.

it di Monica Centanni (Ferlenga 1999); (1927), Premessa

sull’arte popolare; (1928), Questioni

di comune buon gusto (trascrizione, Archivio Pinacoteca

Ghykas, Museo Benaki), trad. it Daria Casiraghi (Ferro 2004); (1933), A

proposito di un Congresso, trad. it Daria Casiraghi (Ferro

2004); (1946), La ricostruzione e lo spirito della tradizione,

trad. it Daria Casiraghi (Ferro 2004); (1951), Lo spirito

della tradizione, trad. it di Monica Centanni (Ferlenga

1999); (1950-51), Il problema della forma, trad.

it di Monica Centanni (Ferlenga 1999); (1958), Note

autobiografihe, in “Zygos”, numero

monografico, n. 27-28, 1958, trad.it di Monica Centanni (Ferlenga 1999).

PSOMOPOULOS P. (1993) – Dimitris Pikionis:

An

Indelebile Presence in Modern Greece. Ekistics, vol. 60, 362-363.

YANNOPOULOS P. (1909) – “La

linea

greca”. To trito mati, 2-3, 1935 [Greek].

YOURCENAR M. (1989) –

“Karagöz e

il teatro delle ombre”. In: Id., Pellegrina e

straniera, [trad. it. di E. Giovanelli]. Einaudi, Torino.

VASSILIOU I. (1936) – “La Casa

popolare”. Technika Chronika, 17-01 [Greek].