Architecture as Life

Reading La città per tutti – a selection of Paulo Mendes da Rocha's writings, edited and translated into Italian for the first time by Carlo Gandolfi[i] – feels like stepping into a sort of personal diary. Leafing through the pages, lingering on the short, incisive sentences illustrated by sketches drawn with the finest of strokes, allows the reader to share in the secrets of a sensitive, attentive and receptive architect, and to grasp essential information that appears not to be known. A collection of nine excerpts constitutes the structure of the volume, exemplifying a series of themes addressed by the architect's thought and work. Notes, speeches, personal reflections, which do not stem from a coherent theoretical-critical corpus, but rather from a declaration of poetics that mixes a certain spontaneity and briefness – typical of some great figures of Lusophone architecture – embedded with a profound wisdom that comes from the awareness that Mendes da Rocha embodied throughout his experience as an architect and teacher of the civic and social purpose with which the role of the architect is endowed.

The key to understanding this volume is provided by the editor's concluding essay, L'architetto che giocava con gli aquiloni (The Architect who played with dragons), in which the recollection of personal encounters and the analysis of the master's thought come together in the human portrait of a mythical figure who is both distant and friendly, who, in those «sentences that often seem like aphorisms, almost notes, milestones to which one must always return», discovers evidence that can be compared to the «programmatic points of a manifesto»[ii]: the relationship with nature, history and the city, personal experience, lived experience as the sum of the moments necessary for the formation of a design conscience, and again: living, technology, social justice and the development of a design conscience. The relationship with nature, with history and with the city, personal, lived experience as the totality of the necessary moments for the development of a design sensibility, and again dwelling, technology, social justice, the development of the territory, America. Vast themes – crucial for the architectural culture of the 20th century – elaborated with ease by means of a direct way of expression that comes from the curious and rigorous way of to work, consisting of repeated actions – building light paper models, drawing on the blackboard, talking while smoking a cigarette[iii] – that invite us to consider the project as an operation of great simplicity that punctuates the flow of life.

Mendes da Rocha's life, however, was not as simple. Expelled from the Universidade de São Paulo in 1969 by decree of the military dictatorship, only to be readmitted a decade later, the most fertile period of his architectural production coincided almost entirely with his teaching. By the 1980s, Brazil had already defined its image to the world – superficially described as minimalist brutalism[iv] – but Mendes da Rocha's work, although associated with this process, was not the subject of research and publications until the mid-1990s[v]. Among the most recent ones, La città per tutti, represents a further step in the understanding of a figure who is particularly topical for his attention to the political dimension and social relevance of the architect's profession.

Among the many themes that emerge in the texts, technique plays a central role. For Mendes da Rocha, architecture is first and foremost a manifestation of a precise building awareness, a fundamental instrument of formal control and a guarantee of progress. «I have become accustomed to placing my trust in the transformative power of technology», he writes in Genealogia dell’immaginazione, «in the foresight and vision that, despite the misery of my country, design useful and desirable actions, that fulfil promises and hopes with a solemn productivity»[vi]. It was in Brazil, Luigi Snozzi noted after one of his journeys, that «one found oneself in a world where the hope for a better future was not only the common hope of all, but the impulse behind every idea and every activity»[vii]. A cheerful industriousness governs the correct management of the building practice, which translates into a rigorous elegance of form, generated by a clear and coherent relationship between structure and space, between economy of means and execution, a "nonchanlance"[viii] as Gandolfi defined it in another of his writings, that can be found in buildings such as the Brazilian Pavilion in Osaka (1970) or the Museu Brasileiro da Escultura (1988) – that comes not so much from an imaginative intuition as from a «particular procedure for mobilising knowledge, that of architecture», an operative practice capable of shortening the distance between «reason and imagination»[ix]. It is the «rigor da técnica que tudo fique em pé»[x] – the ability of technology to allow things to stand – that underpins the design process, constitutes its reason and measures its consequences, and it is its application that manifests «man's ability to transform the space in aimed at which he lives, on the basis of a social interest and through an open vision the future»[xi].

There is no separation between the space of the city and the space of architecture, which converge to form an idea of collective life, confident in the future. The quest for an inclusive and democratic social order, with the aim of disrupting the physical segregation imposed on the contemporary city by market economies, is a militant operation that takes shape in a series of open urban devices, developed in sections in the countless sketches, such as the Praça do Patriarca (1992) or the Museu dos Coches (2015), in which a recurring series of spatial mechanisms – passageways that cross on several levels, spatial transitions marked by the elements of construction – configure places that are available to accommodate possible manifestations of the city for all, imagined as «a kind of belvedere from which reality can be observed, understood above all as a projection into the future and a vision of a city that is an aspiration for all»[xii].

For Mendes da Rocha, space is public by definition: the private (which «exists only in our minds»[xiii]) tends to dematerialise in the space of the city, defining a two-way permeability of people and atmospheres. This approach recurs not only in the large urban buildings he designs, but also in the dwellings - as in his House in Butantã (1960) - where living takes on a political value, assuming the conditions of the city. «However small the house may be as a city, it does not escape the nomoi that regulate collective space. Architecture is and remains everyone's business»[xiv]; a primordial and inherited characteristic of Mendes da Rocha's way of doing architecture, by his own admission: «the notion of protection is absent in Brazilian architecture [...] you enter through one door and leave through another»[xv].

It is worth asking, at a time when the idea that architecture can intervene in domains beyond its traditional disciplinary boundaries has established a firm hold, to what extent the architect should engage in a kind of militancy against a seemingly unbreakable system. «Long live the resistance!»[xvi] is how Snozzi urged Mendes da Rocha to continue the fight for his ideas. Perhaps today, more than resistance, it is a question of rethinking an active commitment to a more humane architecture, based on «a practice of care and attention [...] flexible and in love with life»[xvii], which can act as a panacea for the city's diseases[xviii].

Reading Mendes da Rocha's words in La città per tutti is an invitation for us to walk in that direction, joyfully.

Luigiemanuele Amabile[i] The editor’s publications on Paulo Mendes da Rocha include: Gandolfi C. (2018) – Matter of Space. Città e architettura in Paulo Mendes da Rocha, Accademia University Press, Torino e Gandolfi C. (2023) – Paulo Mendes da Rocha, infraestructural, Ediciones Asimétricas, Madrid.

[ii] Gandolfi C. (2021) “L’architetto che giocava con gli aquiloni”. In P. Mendes da Rocha, La città per tutti, a cura di C. Gandolfi. Nottetempo, Milano, 100.

[iii] See the documentary film It's all a Plan / Tudo é projeto, directed by Joana Mendes da Rocha, Patrícia Rubano, Brazil, 2017 (74'), presented at the Milan Triennale on 7 June 2022.

[iv] Gandolfi C., Matter of Space, cit., 234-245.

[v] See Aa. Vv. (1996) – Mendes da Rocha. Gustavo Gili, Barcelona; Spiro A. (2002) – Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Bauten und Projekte. Niggli, Sulgen; Artigas R. (a cura di) (2007), Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Projects 1957-2007. Rizzoli, New York; Pisani D. (2013), Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Tutte le opere. Electa, Milano.

[vi] Mendes da Rocha P., “Genealogia dell’immaginazione”. In Op. cit., 13.

[vii] Snozzi L. (2002), “Long Live the Resistence!”. In Spiro, op. cit, 9.

[viii] Gandolfi C., Matter of Space, cit., 234-245.

[ix] Mendes da Rocha P., op. cit., 15-16.

[x] Dal Co F. (2006) – Paulo Mendes da Rocha: Listen to and observe a master. The Hyatt Foundation/The Pritzker Architecture Prize, New York.

[xi] Mendes da Rocha P., op. cit., 17.

[xii] Ivi, 74.

[xiii] Gandolfi C., Ivi, 105.

[xiv] Biraghi M. (2021) – Questa è architettura, Einaudi, Torino, 150.

[xv] Mendes da Rocha P. (2002). In Spiro, op. cit., 27.

[xvi] Snozzi L. (2002). In Spiro, op. cit., 9.

[xvii] Ingold T. (2021). Corrispondenze, Raffaello Cortina, Milano, 15.

[xviii] Biraghi M., op. cit., 152.

Scheda libro

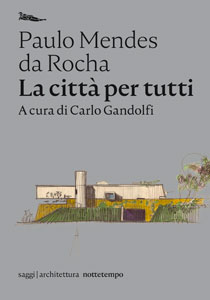

Author: Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Editor: Carlo Gandolfi

Title: La città per tutti. Scritti scelti

Language: Italiano

Publisher: Nottetempo

Features: 16x22 cm, 112 pages, paperback, black and white

ISBN: 978-88-7452-900-1

Year: 2021