Early modernism in Zagreb. Novakova street

Lorenzo Pignatti

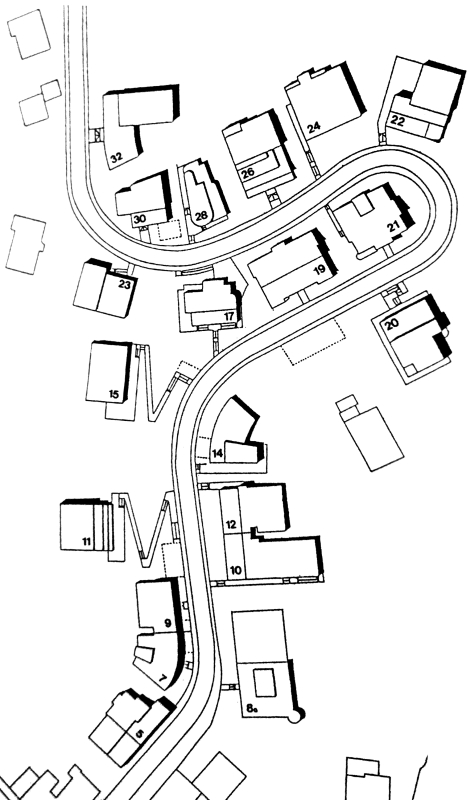

Fig.

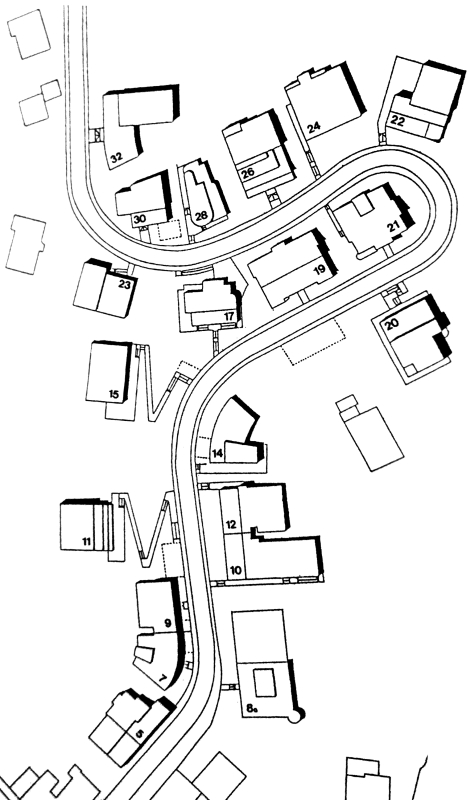

1 - Plan of Novakova street, Zagreb.

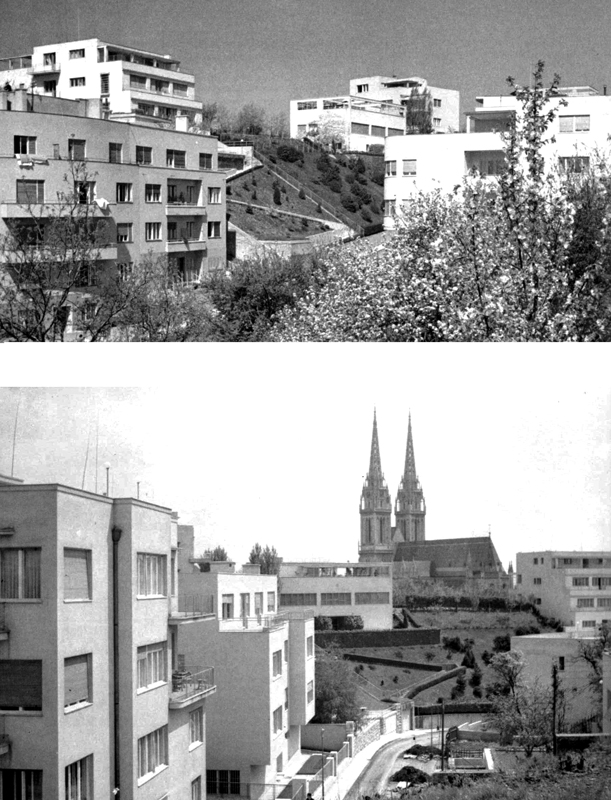

Fig.

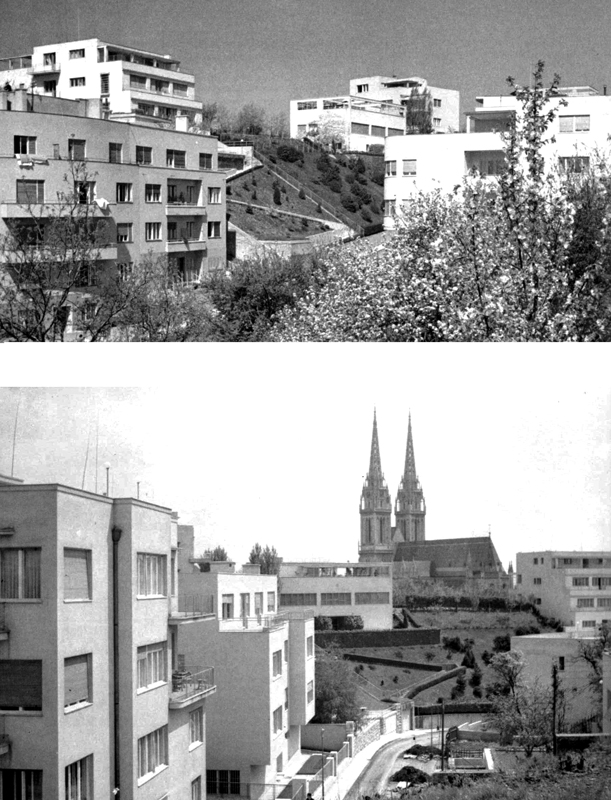

2 - Views of the buildings along Novakova street, Zagreb 1939 (from

Project Zagreb. Transition as Condition, Strategy, Practice, Barcelona

2007).

Text

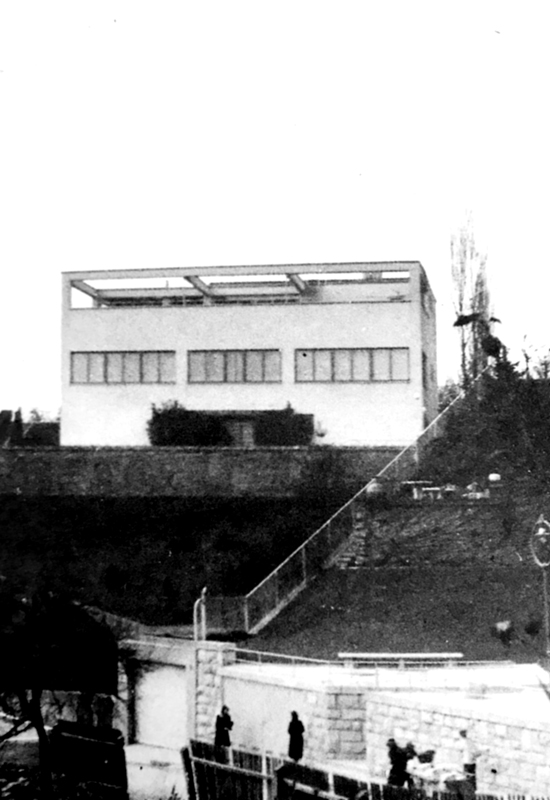

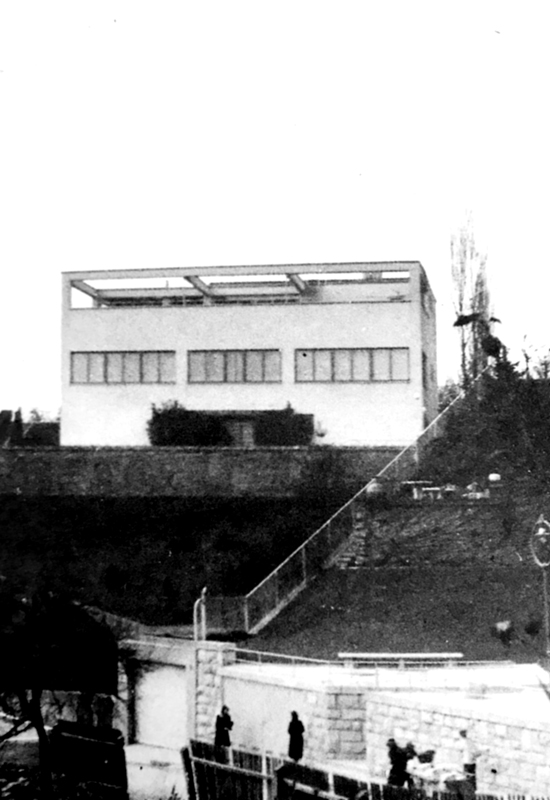

Figg.

3-4 - S. Gomboš and M. Kauzlarić, Spitzer House Novakova street n.

15, Zagreb 1931-1932. Historical photo and current view.

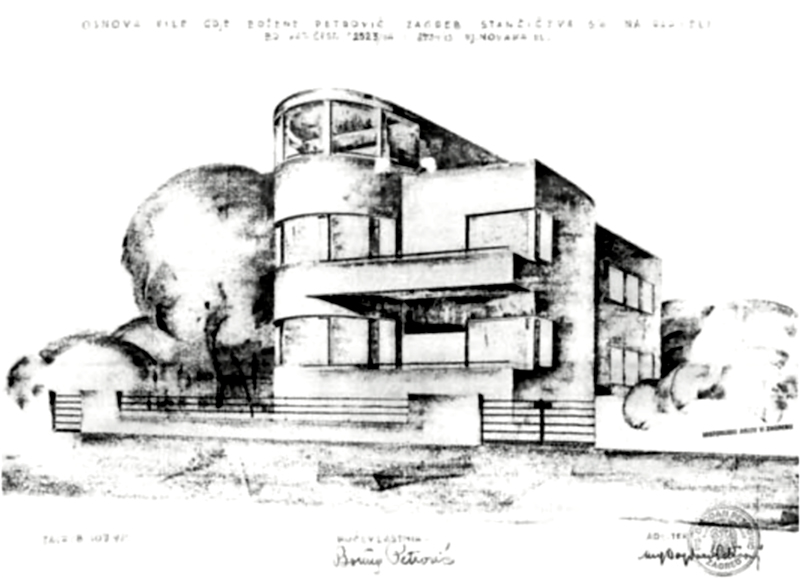

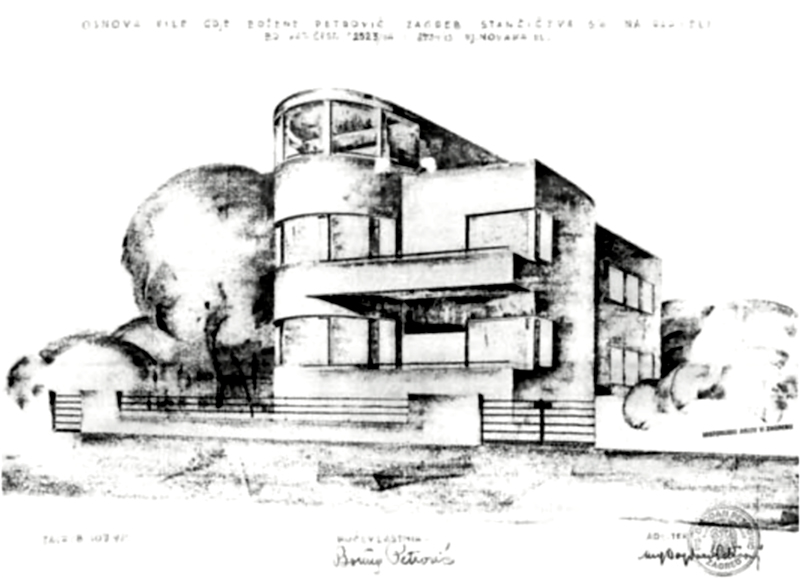

Fig.

5 - B. Petrović, Novakova street n. 28 perspective, 1932 (from

Bešlić T. Urban Villas in Novakova street in Zagreb by architect

Bogdan Petrović, Zagreb 2010).

Fig.

6 - B. Petrović, Novakova street n. 28, present view, Zagreb 1932.

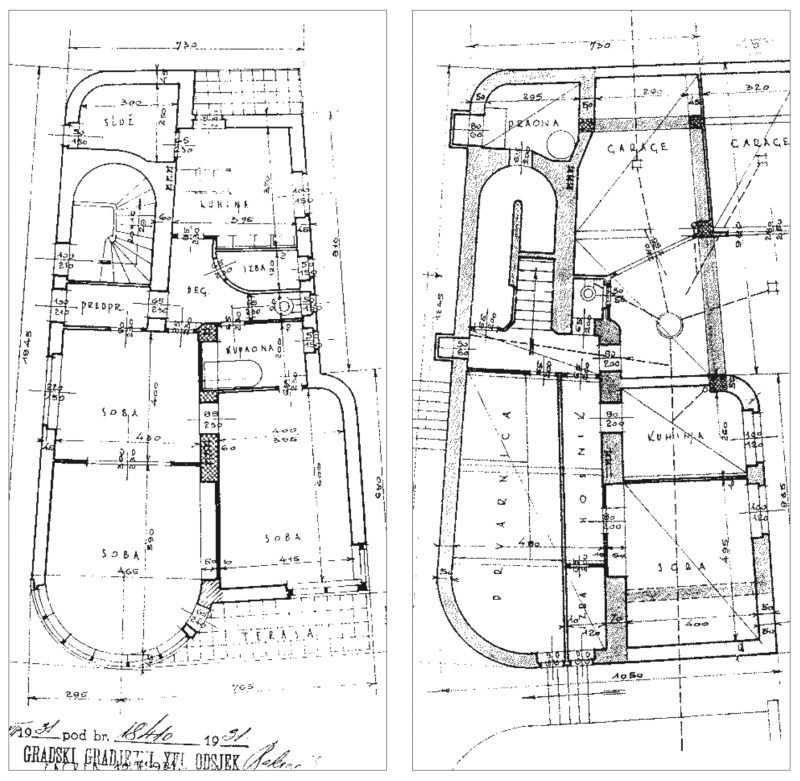

Fig.

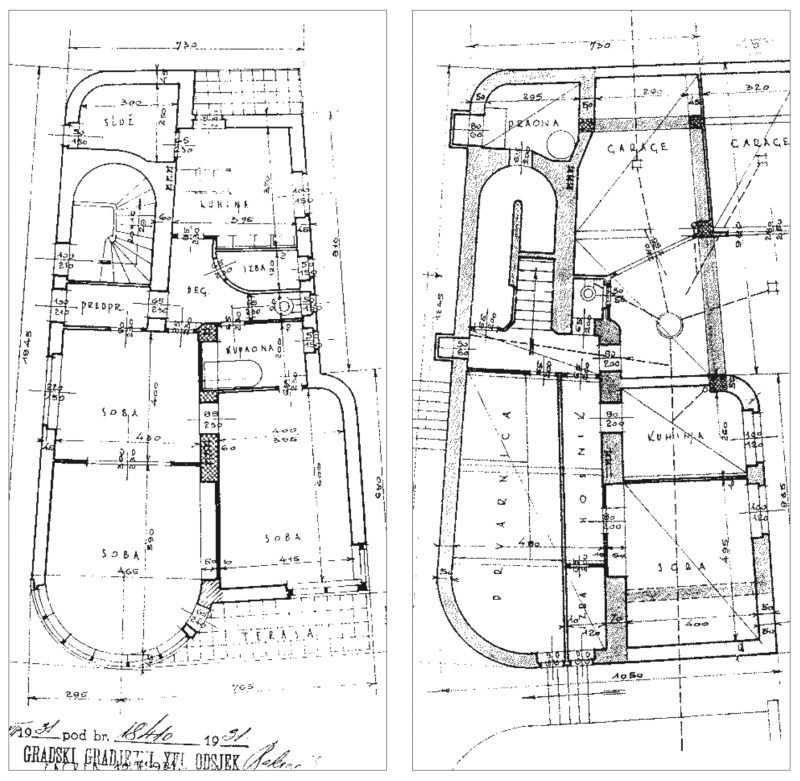

7 - B. Petrović, Novakova street n. 28 plan, 1932 (from Bešlić T.

Urban Villas in Novakova street in Zagreb by architect Bogdan

Petrović, Zagreb 2010).

Fig.

8 - B. Petrović, Novakova street n. 32 present view, Zagreb 1938.

Fig.

9 - Ante Grgić, Novakova street n. 20 present view, Zagreb.

Fig.

10 - Ivo Kulišek and Ivan Senk, Novakov street n. 17 present view,

Zagreb 1932.

Fig.

11 - Moses Lorber, Novakova street n. 21 present view, Zagreb 1935.

Fig.

12 - S. Gomboš and M. Kauzlarić, Novakova street n. 24 present view,

Zagreb 1935-36.

Fig.

13 - S. Gomboš and M. Kauzlarić, Novakova street n. 24 present view,

Zagreb 1935-36.

Not much is known about the beginning and development of

architectural modernism in cities of the western Balkan region. For a

long while this region was considered an “in-between” area,

a region that was not able to express its own identity since it was

characterized by a diversity of social, religious, political and

ethnical tensions. This essay intends to prove the opposite and claim

that somehow there was a very interesting development of modern ideas

related to architecture and urbanism in most of the cities of the

Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the early part of the XXth century.

Belgrade, certainly the largest and most influential city of the

region, went through a process of transformation from a an Ottoman city

into a European capital, following, first, Beaux Arts models and then,

modernists ones; Ljubljana, much closer to Austria and central Europe,

went through an amazing period with the architecture and urban projects

by Plečniek; Zagreb saw a very interesting urban expansion with new

developments in the Lower City that integrated experimental strategic

architectural interventions of great value; Sarajevo transformed itself

from an Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian city into a modernist city with

significant projects that proposed a reinterpretation of vernacular

models. Then there was the important but later case of Skopje,

destroyed by a major earthquake in 1963 and reconstructed in the

following years with a master plan by Kenzo Tange. Somehow all these

cities followed their own path towards modernity, each of them with

their own specificity given by local political and cultural conditions

or by the presence of significant individuals, but eventually always

open to absorb fresh ideas that were coming from other parts of Europe.

This essay intends to analyze the development of modern architecture

in Zagreb, not the largest city in former Yugoslavia but one that could

offer a completer and more layered picture of the development of modern

architecture due both to a sophisticated internal cultural scene and to

its openness to external influences.

There were some anticipations in Zagreb of a new vision with the

presence of Viktor Kovacić and Drago Ibler. Kovacić, a pupil of Otto

Wagner, was the author of the headquarters of the Central Bank of

Croatia (1923-27), still a neo-classical building but certainly one

that presented a simple and austere revision of classicity and one that

certainly created a rupture with the predominant previous eclectic

trend, a position not very different from Plečniek’s work in

Ljubljana. Ibler was an architect, theoretician and academic of a

distinguished value in Zagreb in the early Twenties; he had studied in

Dresden, was part of the architects that were in contact with Le

Corbusier and then worked with Poelzig in Berlin. He founded the second

Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb at the Academy of Fine Arts, an

active school inspired to the ideals of modernism that created a

consistent number of new graduates and gave origin to what will be

called “the school of Zagreb”. He also was a founding

member of the group (and magazine) Zemlja (Earth) that

operated in Zagreb from 1925 to 1935 as a progressive movement composed

by architects, artists and sculptors that were proposing a shift

towards modernity, advocating that «it is necessary to live in

the spirit of our own time and create accordingly with it». These

architects were not following a specific “style” and their

work was not at all consistent; however, their architecture was

certainly original and simple, anticipating a “purism” that

will then generate the development of modernity.

General cultural context

Across Europe the Modern Movement was in fact already a reality

during the late Twenties and the early Thirties of the XXth century,

with different manifestations of a new architectural vision that was

certainly influencing the different cities of the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia, including Zagreb.

After the First World War the National University Library in Zagreb

received continuously journals and publications in major foreign

languages, but mostly from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Because

of the proximity with Vienna and Prague, the work of Adolf Loos with

the Steiner house in Vienna (1910) or Muller house in Prague (1930) was

certainly well known, mostly because several architects studied in

those cities. The De Stijl movement had already developed in the

Nederland and Stjepan Planić asked Theo Van Doesburg to write an

article for the journal The Croatian Review and Planić himself wrote a

unique monograph on the modern trends in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

entitled Problems of Modern Architecture where a large number

of architects from Croatia and Serbia published their own work. The

Croatian architect Ernest Weissmann, who collaborated with Adolf Loos

(1926-27) and Le Corbusier (1927-28) and was part of the group Zemlja,

was an active member of CIAM that had its first congress in 1928 in

Switzerland.

Major references across Eastern Europe were the work of Walter

Gropius at the Bauhaus in Dresden, the work of Mies van der Rohe with

his villa Tugendhat (1929-30) in Brno and, finally, the work of Le

Corbusier, with projects such as villa Stein 1927 and Ville Savoye

1929, considered all landmarks of the new modernity.

Main influences were coming also from other cities in the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia. In Belgrade Milan Zloković, who studied in Graz and in the

early Twenties, had followed some courses in Paris, has built for

himself a villa in 1927-28 very similar to the work of Loos and other

early modernists. The photographs of this villa were showed in 1929 in

one of the first exhibition on modern architecture and received

immediate interest. Zloković was also the author of another house in

Belgrade, villa Šterić (1932), where the main volume is

decomposed in several smaller parts all painted in different colors,

recalling the work of the De Stjil movement. In Belgrade in 1929 a

group of four architects, including Zloković, founded GAMM, that had as

a primary scope the development of modern architecture in the current

practice and, at the same time, the dismiss of the prevailing

eclecticism of the time.

Certainly, the international exhibition of the Weissenhof in

Stuttgart in 1927 organized by the Werkbund and coordinated by Mies van

der Rohe, became the main international window on the social and

architectural innovations proposed by the Modern Movement, where

Behrens, Poelzig, Hilberseimer, Oud, Le Corbusier, Gropius and van der

Rohe himself participated with original projects, main reference for

all the countries in Europe, including Croatia.

At the same time, besides the major role played by important figures

like Viktor Kovacić in Zagreb and Joze Plečnik in Ljubljana, there was

a consistent number of other architects in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

that started their own careers with projects and buildings of a clear

innovative character, showing a shift towards modernity or, at least,

towards an early purism that anticipated the Modern Movement. These

architects were I. Vurnik, V. Subić, M. Fabiani in Slovenia; M.

Zloković, B. Kojić, M. Belobrk and N. Dobrović in Serbia; D. Ibler, S.

Planić, S. Löwy, J. Pičman, A. Albini and V. Antolić in Croatia

and, finally, the Kadić brothers and a bit later D. Grabrijan and

Neidhardt in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Some of these architects had studied

abroad in Austria, Czechoslovakia or Hungry, had visited major

international events such as the International Exhibition of Modern

Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925 that contained the Esprit Nouveau Pavilion by Le Corbusier and had worked in prestigious offices in Europe.

Zagreb

During the Thirties Zagreb went through an interesting period of

urban planning that originated from the necessity of mediating between

the Master Plan of 1923 and the development of the Lower City. One of

the issues that needed to be resolved was the conciliation between the

existing rural structure and the new layout of regular streets that had

been already extended in the same years. The solution was innovative

and consisted in the creation of large urban blocks that had external

compact perimeters with new buildings aligned to the new street,

enclosing internal areas that incorporated the rural network of paths

as well as the existing agricultural buildings. This solution had the

effect of creating almost two superimposed cities, one large with a

regular layout that was following the modern needs of movement and a

second one, internal to the urban blocks, that maintained its

agricultural character. In the office for the Master Plan, that was

created for the realization of the new urban layout, there were young

architects, many of which had returned from their studies in Berlin,

Vienna or Prague and were eager to bring to their own city what they

had learned abroad. Moreover, the city promoted a series of

competitions for specific urban lots, trying to put together the needs

of the private ownerships with the desire of creating innovative

solutions coherent with the master plan. The result was that several

architects proposed strategic interventions to reinforce this master

plan either by connecting the new network of streets with the inner

part of these blocks or by resolving specific urban conditions, such as

urban corners. Among these we could list the ones designed by Drago

Ibler (Wellisch Block, 1930), by Stephan Planić (Nepradak

building,1935), by S. Löwy (Radovan block, 1934), and the large

and central Endowment Block (1930).

Novakova Street

However, this paper intends to present more in detail a similar

example of a coherent urban intervention of the early Thirties

represented by a residential development built on a hill just beside

the cathedral, along Novakova street, connecting the lower town with

Šalata Hill.

Novakova street consists of a series of projects done by different

architects in Zagreb that included originally independent buildings of

small dimensions aliened along the curvilinear and ascending path of

Novakova street.

Differently from the Weissenhof, Novakova was not conceived as a

working-class district, but was rather for a higher and richer social

class. It was neither state – nor city – sponsored, nor did

it have any sort of official support. Given the critical economic

crisis of the late Twenties/early Thirties in Croatia, people were

reluctant to deposit their money in banks and preferred investments in

the residential construction that could provide a steady income in rent

money. Thus, private capital assumed the dominant role where private

investors became the main clients who commissioned architectural

designs. Most of them were architects, lawyers, doctors, industrials

and merchants and their position in the society can be illustrated by

the presence of a maid’s room in most of the villas. Thus, in

Zagreb the shift occurred from the construction of complex estates to

small residential buildings and family houses. The owners of the

parcels could choose their own architect and very often the same

architects were owners, designers, structural engineers, and

contractors. All the buildings had to follow specific regulations about

density, height, and depth of construction and the only bureaucratic

step was the approval from the Facade Commission that granted the

homogeneous character to Novakova Street, insisting on the elimination

of any sort of ornament in order to maintain a consistent formal

vocabulary and control of the massing to ensure views between houses.

Following the renewed cultural conditions above mentioned and the

general demands, the built projects abandoned any sort of reference to

the art nouveau decoration or neo-classical details and rather searched

for simple compositions of volumes and regular solutions with simple

and plane facades. Most of the buildings were constructed in reinforced

concrete, following what had already been done by Loos, Le Corbusier,

and others, had simple stereometric forms, had windows and openings

without any sort of frames or moldings, had open balconies projecting

out of the volumes, had flat roofs or open terraces at the top levels

and most of them were painted in white color. All the villas followed

the morphology of the site and adapted themselves to the changes in the

level of the street, integrating themselves into the landscape.

Between 1931 and 1941 twenty villas were constructed, most of them,

in the early period, single-family houses and later 3-4 storeys

apartment buildings. There were fifteen Croatian architects that built

the villas; among the total of twenty, three were designed by S.

Gomboš and M. Kauzlarić and six were designed by Bogdan Petrović.

Villa Spitzer (Novakova 15), designed by S. Gomboš and M.

Kauzlarić, is probably the most well-known of this beautiful street.

Kauzlarić was a student of Drago Ibler and a member of Zemlja and, in the early twenties, the two started their own office with work both in Zagreb and Dubrovink.

Villa Spitzer is a single-family house built on three levels and

composed by a very simple volume, built at a higher level in relation

to the street and with open views towards the cathedral of Zagreb in

the back. A family house with rooms for servants, an elevator that

connected the kitchen to the dining room on the first floor, a strip of

horizontal windows that allowed connection with the outside space.

The plan is a simple rectangle with a very simple organization of

the internal spaces, where the last floor is primarily an open terrace

with a concrete structure that creates a canopy. The main façade

is simply articulated with strip horizontal windows on the second floor

and an open loggia at the last level. The villa embodies the famous

“five points” of modern architecture established by Le

Corbusier in 1926, having a free plan and free façade, strip

windows and a roof garden, all features that create a direct parallel

to the early work of the Swiss master.

Even if the villa went through significant changes that ruined its

own original design, Villa Spitzer, for its own simplicity, its year of

construction (1931) and for its evident references to the work of the

big masters of the Modern Movement, must be recognized as a landmark of

modern architecture in Zagreb and in the entire Croatia.

As mentioned, Bogdan Petrović was another of the main architects of

the development of Novakova street, building six houses (Novakova 10,

11, 23, 26, 28 and 32), considering that House 28 was his own house.

The projects by Petrović are simple and articulated; there is often the

desire of combining simple rectangular volumes with circular projecting

ones that offer to the building a strong dynamic quality. In House 28,

the intersection between a three levels cylindrical volume and a series

of smaller rectangular ones on the side becomes the main feature of the

house, remembering projects done by Eric Mendelsohn or Alberto Sartoris.

The same happens to a lesser degree in House 10 where the building

ends in one corner with a cantilevered circular volume with strip

windows and a terrace on top. The overall composition is very effective

and the final result indicates a very mature ability of combining

different volumes and geometries and offering a dynamic quality. House

32 is purely a volume with a continuous curvilinear façade that

follows the bend of the street. The different levels have linear

balconies that offer a space of mediation between the interior and the

exterior, offering open views given the high location of the house on

the top of the hill. All Petrović’s projects show consistent

research towards modern models, somehow different from Villa Spitzer,

thus showing a diversity in the architectural vocabulary in the

buildings along Novakova street but a rather a strong consistency in

dealing with modernism.

Conclusions

Besides the Weissenhof in Stuttgart or eventually the much larger

White City built in Tel Aviv in the Thirties by German-Jews architects

that returned to Israel, we are not aware of such a coherent urban

development done in the early Thirties like Novakova street. In fact,

it stands as a little-known example in architectural literature that

originates in Zagreb from single individuals and investors that

followed the culture of the moment and understood the economical and

cultural benefits given by a shift towards modernism, both in

architectural typology, language, technology as well as in

entrepreneurship.

Bibliography

BEŠLIĆ T. (2010) ̶ Urban Villas in Novakova street

in Zagreb by architect Bogdan Petrović, Prostor, Zagreb.

BLAGOJEVIĆ L. (2003) ̶ Modernism in Serbia. The elusive

margins of Belgrade Architecture 1919-1941, Cambridge and

London MIT Press, Cambridge.

DOKIĆ, DEJAN (2007) ̶ Elusive Compromise: The

Inevitable Specificity of Interwar Yugoslavia, Colombia

University Press, New York.

GRIMMER V., MARDULJAS M. e RUSAN A. (a cura di) (2010 ) ̶

Continuity and

Modernity: Fragments of Croatian Architecture from Modernism to 2010,

Arhitekst, Zagreb.

KULIĆ V., MARDULJAS M. e THALER W. (a cura di) (2012 ) ̶ Modernism in-between.

The mediatory architecture of socialist Yugoslavia, Jovis

Verlag, Berlin.

LASLO A. (2010) ̶ Architectural Guide, Zagreb

1898-2010, Arhitekst and Društvo arhitekata,

Zagreb.

PIGNATTI L. e GRUOSSO S. (a cura di) (2017) ̶ Crossing Sightlines. Traguardare

l’Adriatico, Aracne, Rome.

PIGNATTI L. (2019) ̶ Modernità nei

Balcani, da Le Corbusier a Tito, LetteraVentidue,

Siracusa.