The Socialist Sarajevo: between heritage and modernity

Stefania Gruosso, Emina Zejnilović

Fig.

1 - R.Kadić, The residential ensemble of Džidžikovac built following

the orography, Sarajevo 1953. Photograph by Stefania

Gruosso, 2018.

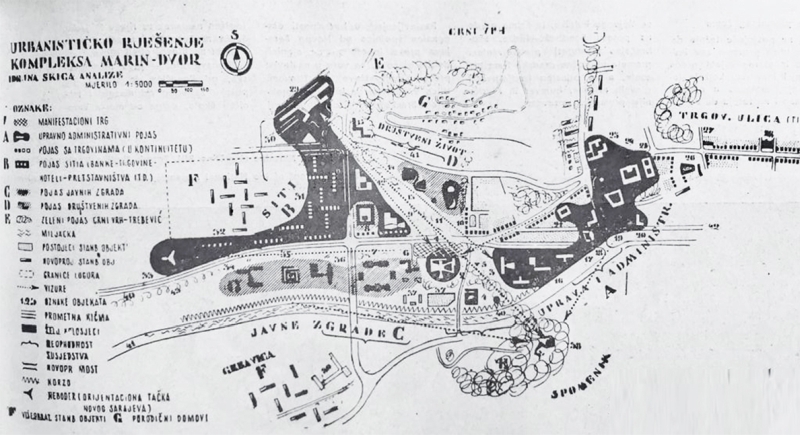

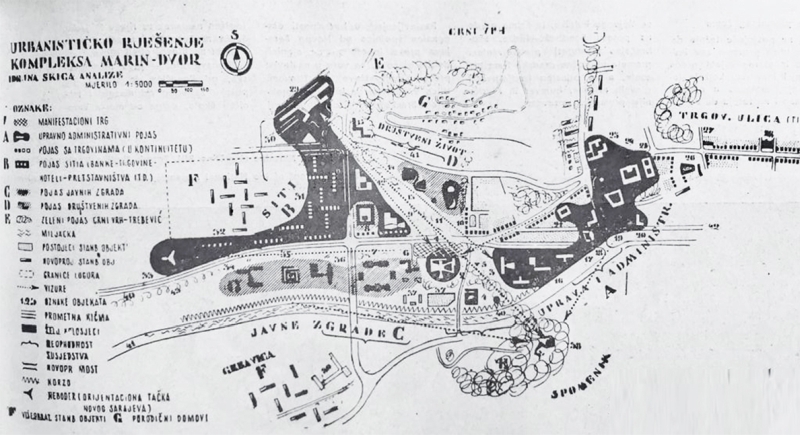

Fig.

2 - Neidhardt, Master plan of Marindvor, 1960.

Fig.

3 - J.Neidhardt, The vertical skyscraper of the Institution of Bosnia

Herzegovina, the square and the horizontal Parliament building,

Sarajevo 1974-1982. Photograph by Stefania Gruosso, 2016.

Fig.

4 - N. Mufti and R. Dellale, Ciglane, Sarajevo 1976-1979. Photograph by

Stefania Gruosso, 2018.

Fig.

5 - The residential complex Alipasino polje. © Aida

Redzepagic, 2020.

Fig.

6 - View of Alipasino polje from Igman mountain. © Emina

Zejnilović, 2023.

Fig.

7 - The Dvorana Mirza Delibašić, Sarajevo 1969.. Photograph

by Stefania Gruosso, 2018.

Fig.

8 - B. Magaš, E. Šmidihen e R. Horvat, the

Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo 1958. Photograph

by Stefania Gruosso, 2016.

Introduction

Sarajevo is a city in the middle - both geographically and

culturally a condition that made it, for centuries, a city of crossroad

and a meeting point of cultures, ideologies, and religions. The

multiple essence of this city is the result of a continuum of

invasions, destructions, wars, and reconstructions. The history of the

city began with the Ottoman domination, when Sarajevo was transformed

into the most “Eastern” city in Europe, following

Istanbul’s example. The Ottoman domination was followed by the

rule of Austro-Hungarian Empire, which aimed at adapting the city to

European standards. After the ferocity of the two world conflicts the

city was destroyed and impoverished and facing the problem of

reconstruction.

In the mid-20th century, during the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and

Herzegovina (SRBiH), the city was characterized with increasingly

favorable social, economic, and subsequently architectural conditions.

Significantly heightened pace of investment construction, progressively

complex spatial demands, and a favorable climate of general social

enthusiasm, generated projects of brave dispositional ideas and new

formative approaches. The rise of urban and industrial society caused

considerable increase in migrations to the capital which demanded

large-scale urban development, as well as mass production of built

environment, particularly of residential unit stock. To remedy this

growth the General Urban Plan 1965–1986 was designed by the

Institute for Planning and Development of Sarajevo. The document

designated its longitudinal extension, in east-west direction, and

initiated its rapid expansion from a narrow valley of river Miljacka to

the wide area of Sarajevsko polje.

The contemporary layout of the city is characterised by series of

different layers that are not overlapping but are perfectly aligned

with one another. Each individual layer has its own

historical-morphological identity and witnesses a piece of the

city’s history in which the socialist Sarajevo is easily

spatially identifiable for its urban extension, the change of city

scale, and the vertical development of its architectures.

Socialist Sarajevo and Modernization of the City- The role of Neidhardt and impact of Le Corbusier on the city.

The empowerment of urban proletariat and growth of industrial

society was the impetus the government used for building strong

socialist state. These occurrences were seen as both ideological and

pragmatic tools, which in combination with the established

self-management system impacted all aspects of living. The role of

architecture in constructing the Yugoslav nation, control of

socio-cultural life, and communication of the Yugo-Slavic socialism

doctrine was tremendously important. The unique political identity,

based on continuous balancing between East and West, resulted in the

equally distinct, the “in-between” architecture

(Mrduljaš & Kulić, 2012), that combined the communist

egalitarianist ideology with the Western aesthetics and technology.

In his book Nova arhitektura Bosne i Hercegovine – 1945-1975,

one of the most renowned Bosnian architects, Ivan Štraus,

identifies four developmental periods of Bosnian architecture

modernization (Štraus, 1977).

The complex process was initiated immediately after the WWI, and was

mostly focused on immense construction marked by the influence of

limited number of architects, and modest economic and investment

possibilities. These were the turbulent years, the years of ideological

split with Stalin’s Russia, and strict social-realism, and the

turning point towards economic reforms, decentralisation, and

liberalisation. Prominent individuals, creators of the pre–WWII

Sarajevo Moderna, such as Dušan Grabrijan, Muhamed and Reuf

Kadić, Helen Baltasar, Juraj Neidhardt, Jahiel Finci, and others,

affirmed Bosnian architecture within Yugoslav framework and set the

path for continuation of modern architectural aspirations. The search

for new architectural interpretation was mostly reflected through

positive reminiscence of early Moderna, best seen in the exemplary

residential ensemble in Džidžikovac (Fig.1) built by Kadić brothers in

1948, as well as the suggestion made for the modern urban reform of the

city.

In the years to come, architecture of Sarajevo was strongly

influenced by the schools of architecture from Zagreb and Belgrade, but

also the work of Le Corbusier’s student and one of the most

significant builders of Sarajevo, Juraj Neidhardt. He argued for the

revitalization of the “man tailored city” idea, and the

establishment of the “Bosnian pole in architecture”,

grounded on the aspiration to transcend inherited architectural values

into new, modern interpretation. (Grabrijan & Neidhartd, 1957) In

his 1960s suggestion for the creation of the new city centre in the

area Marijin Dvor, he proposed a “spatial pause” that would

revive the Ottoman philosophy of Sarajevo – the garden city and

be a modernist counterpart of Bascarsija (Fig.2). Recommended urban

solution was dominated by a form of green pedestrian strip, which would

lead to the main traffic road and beyond, in the direction of mountain

Trebevic, Tired of “skyscraper-mania”, Neidhardt suggested

a business area with accentuated horizontal architectural tendency and

parterre, which is more in tune with traditional doksat architecture

(Neidhardt in Oslobodjenje). Yet he connected the best of both worlds

with his contradictory composition of vertically accentuated BiH

Institutions building, juxtaposed with horizontal Parliament building

and the entrance square (Fig.3).

The “Neidhardt approach” to architecture was based on

harmonious symbiosis of traditional principles, the «neighborhood

cult» and the «right to a view», with contemporary

style of clear forms and minimalist expression. In his work he managed

to creatively reinterpret this idea through numerous iconic buildings,

such as Faculty of Philosophy and Faculty of Natural Sciences and

Mathematics, residential buildings in Alipasina street 11-17, or his

Summer Stage in Ilidza. This created a solid ground for the

modernization of the city that continued in the 1960s and 1970s, when

architecture was increasingly falling under the influence of regional

but also first graduates of Sarajevo School of Architecture.

At the time, architectural demands were more complex in size and

content, with new formal expression and spatial dispositions,

influenced by contemporary technology and innovation, rise of consumer

society and strengthening of Yugoslav nation. The general

characteristic was a tendency to create architecture of technical

perfection as an aesthetic ideal, (buildings of Energoinvest,

Unioninvest, Yugobank, etc) while during the 1970s, design was mostly

influenced by international brutality, particularly evident in the

building for Radio and TV Home, Skenderija the sports and recreation centre, the fallen icon of Sarajevo department store Sarajka,

as well as number of health, hospitality, and administration edifices

to the city (Straus, 1987). Perhaps as never before, architecture was

unburdened by local folklore elements, recognizable by fine artistic

and technical literacy, establishing an authentic legacy which was the

original Yugoslav interpretation of European architectural tendencies.

Unmatched in its expression, perfect balance between two worlds.

Residential architecture: Ciglane and Alipasino Polje

The process of modernization in design of residential architecture

was grounded on the socialist idea of equivalence embedded within

Yugoslav culture. It was ‘the principle of class rather than

identity’ that was given the priority, believing that a just

social order would resolve any nationalist issues relating to the

different ethnic groups. Residential architecture used its minimalist

aesthetic as a strategy to participate in the organisation of

individual and collective human life (Zejnilovic & Husukic, 2018).

Initially, the architecture of living was restricted by modest

standards and poor construction quality. During the 1950s and 1960s

housing development gained momentum and was characterized by appearance

of new residential typology - unified blocks. In composition, they were

or either fully stripped off any intervention and burdened with the

«overall sensitivity» – or characterized by an

exaggerated number of small scales details and interventions, evident

in the first large residential area, Grbavica I. Though improved in

disposition of living units, conventional architecture that was missing

initially planned accompanied spatial content, was believed to be

lacking in creativity, spirit, and authenticity.

Despite the uniformity in visual expression, much was done in the

following years in reproduction of residential units, which were

becoming more complex in content, more contemporary in spatial layout

and much larger in size. Some of the most significant representatives

of the time are residential settlements, Otoka, Čengić Vila, and

Grbavica II.

By 1971 the population of Sarajevo tripled in size, from 111.087 in

1948 to 359.448 inhabitants, only to grow to a count of 448.519

inhabitants in the following decade (Grad Sarajevo). Needed swift

expansion in residential unit stock was a great burden on the city,

that responded with planned residential construction mostly in the

valley area of Sarajevsko polje (Sarajevo valley).

The jump in demographics and change in social structure of the

population, was also followed with the first wave of illegal settlement

construction on the slopes of Sarajevo, that lasted from the 1960s to

the 1980s. Though hillside residential area – mahala is rooted in

local tradition and is a genuine brand of Sarajevo that still

determines the urban ambience, the frenzied, wild hillside development

was world-apart from the stepped garden image of the XVI century

Ottoman town.

Local architects experimented with new building models and

typologies, while maintaining connections with local traditional.

Architecture of dwelling in mature Yugo-design production, offered new

living style for Sarajevans by proposing, for the first time, the tower

block residential typology. Its finest interpretation is displayed in

housing conglomerate Alipašino Polje, planed by Milan Medić, Jug

Milić and Namik Muftić (1977-1980). At the same time, bold solutions

grounded on traditional model of living were offered in the mega

construction of Djuro Djaković housing complex, known as Ciglane, designed by Namik Muftić and Radovan Dellale (1976-1979).

Ciglane (Fig.4) – the homage of the Ottoman city, is a

terraced type collective living settlement occupying area of 16

hectares, planned for 6000 residents in 1451 living units (Dobrovic,

1973). Located in the western part of Kosevo Valley in the site of

former brick factory, this specific architectural solution reiterated

the concepts of traditional mahala housing around Bascarsija. On a

larger scale, Ciglane was one of the planned segments of spatial

interventions done along the axis of Djuro Djakovć street (today

Alipasina), that culminated with sports centre Skenderija at one end,

and planned Zetra complex on the other.

The basic idea was grounded on continuity of urban structure, and

playfulness of urban morphology in both horizontal and vertical

direction. The picturesque spatial cluster, distinguished by the

freedom of volume, harmonious materialisation, variety in views and

interplay of urban ambience, manages to achieve necessary urban and

residential intimacy regardless of the complex, layered matrix of

streets, squares, parks and passages. This is evident in the offered

urban content diversity: the main pedestrian promenade and the

“gallery” street - above the garages (ground level), the

middle street – “quiet residential street” (1st

level), quiet street residential oasis and vista (2nd

level) (Juric & Islambegovic, 2019).

Recently actualized but back then quite a revolutionary

participatory approach in design, was utilized in the design of

residential units, where the users were able to take part in the design

and evolution of this megastructure through intervention on open

terraces. Additionally, they were envisioned as supplementary areas, on

account of which the units could expand if needed, as flexibility and

adaptability was another major pivotal point of the design.

Opposite to Ciglane, residential complex Alipasino polje (Fig.5-6),

is located on mild slopes of wide Sarajevsko polje (Sarajevo valley),

between two main transportation arteries of the city. It was designed

to house the rising middle classes or the working population of 30 000

inhabitants. (Investprojekt, 1985) Interestingly, it was the first

settlement in Sarajevo larger than 15 hectares, covering massive area

of 65 hectares and providing 8200 housing units (architect Milan Medic

for Municipality Novi grad, 2021). Urban composition is arranged

through a series of 19-storey high buildings, positioned on the

outskirts of the site, which regress to 5 – storey buildings as

they move to the central section of the area. The created

“gated” appearance towards the exterior, is intelligently

softened with the adjustment of built scale, subtle levelling

alterations of large public areas, which with its horizontality

balances out the exaggerated verticality along the edges. Abondance of

common spaces were provided allowing the locals to nurture the cult of

neighborhood and maintain the sense of community. At the same time, the

exterior view to the 19-floor tower blocks, corresponded with global

architectural trends of the time and reflected the state's vision of a

successful, progressive society.

This created an overture to the final phase of Sarajevo’s

«unfinished modernization» - massive city expansion for the

preparations of the 1984 Winter Olympic Games.

Public buildings. From instrument of the regime to icons of the contemporary city

In addition to the residential growth, the architectural panorama of

the city was also enriched through a series of new projects, that were

the expression of the role of architecture in constructing the control

of socio-cultural life. At the same time, architecture confirmed the

interest of the regime to culturally develop the city, through

different aspects and approaches, intending to make Sarajevo a modern

cultural center. Significant spaces for culture were under construction

as instrument through which Tito communicated the modernity of

Yugoslavia to the world.

Examples include the Skenderija Culture and Sport Centre, a

structure whose composition is a clear reference to the work of Le

Corbusier, the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, whose domes resonate back to the Ottoman architecture and the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Sports and Culture Center Skenderija (CSC Skenderija) (Fig.7)

was built in 1969 along the Milicka river in a site close to the new

city centre designed by Neidhardt in the area Marijin Dvor. It was

built as a response to the city's need to provide itself with a place

that could offer sports and cultural activities, with an intention to

improve the living quality. The complex designed by Živorad Janković

with the collaboration of Halid Muhasilović presents itself as an

ambitious work, unique in its intentions, content, dimensions,

remarkable for the new way of interpreting and organizing space.

The spacious composition that reflects the influence of the late (ie

brutalistc) Le Corbousier style (Neidhardt T, 2014) follows a complex

functional program which sees the coexistence of sport, culture and

commerce; a concept of hybrid architecture very close to the

contemporary one. (Gruosso, di Lallo, Pignatti 2022).

A huge podium dominates the composition from street level and is

mostly used for commercial activities, and hospitality activities. The

two main building segments, Dvorana Mirza Delibašić and Dom

Mladih act as a backdrop to the large central public space.

The Dvorana Mirza Delibašić, also called the «concrete rose»,

is a multipurpose arena used both for sports events and competitions,

characterized by large inclined pillars in reinforced concrete placed

on the short sides, which seem to lift the building from the ground.

The Dom Mladih, which means House of Youth, is a multifunctional center

made up of a concrete box, marked by horizontal windows that run along

the entire facade, into which a cylindrical volume is inserted, hosting

a dance hall, an amphitheater, a nightclub and a Youth Center. The

uniqueness and the value of the CSC Skenderija are confirmed by the

fact that the architects received the Yugoslav National Borba Prize,

proclaiming it the best architectural project in Yugoslavia. The work

was revisited and expanded for the 1984 Winter Olympics, which was the

protagonist of new urban transformations for Sarajevo.

Not far from the Skenderija Culture and Sport Centre, the Faculty of

Natural Sciences and Mathematics is located, one of the two faculties

for the University of Sarajevo provided by the master plan of Juraj

Neidhardt for Marindvor.

The project is a clear expression of Neidhardt's theory based on the

idea that an architecture adequate to the nation’s modern

conditions must be built on vernacular foundations.

The structure, that was built in the 1960s, according to the design

of Neidhardt himself is composed by two blocks. The first block

consists of a series of volumes organized around a central space. The

lower part of the first block is finished with an evident rusticated

stone base that is a clear reminiscence of the old city. The second

block is a one-storey building covered by a roof topped by

semi-spherical volumes clad in copper, an intentional reference to the

domes of the traditional Ottoman city. The classrooms inside these

vaulted spaces feature a particularly effective layout and lighting

that filters in from the sides. (Pignatti 2019)

Still in the transitional part towards the new city, along the main

street (Zmaja od Bosne), the Historical Museum of Bosnia and

Herzegovina subtly rises (Fig.8). The museum design by a group of

Zagreb architects, Boris Magaš, Edo Šmidihen, and Radovan

Horvat in the 1958 is perhaps the most international and modernist

project in Sarajevo with its dominant cube forms and clean lines.

The works has been the first prize winner in a public competition for the design of the Museum of Revolution in Sarajevo.

Museum changed its name several times. In 1949 the museum was named

Museum of National Revolution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 1967 Museum

of Revolution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally, by the Law on

Museum activity, adopted in June 1993, museum was renamed to Historical

Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The building consists of a giant

concrete cuboid resting on an almost entirely glazed base which appears

to float atop a white stone podium. The entrance is characterised by a

large staircase made of stone. The uniqueness and the architectural

values of the Museum is well synthesized by the words of the Prof.

Stjepan Roš:

The building of the Museum of the Revolution manifests the pure

architecture of Mies van der Rohe. It is constructed of

“boxes,” transparent and full. The glass-lined breathable

skeleton stretches on a white stone pedestal, on which rests a full

stone box […] Spaces are extroverted, clearly oriented towards

the inner garden. Nine columns — slender trees — contradict

their own actual function because it looks like they break through and

do not support. Free placement of walls gives the impression of moving

billboards and an “open free plan”.

The socialist Sarajevo towards the future

Forty years since the ending of Tito’s era the capital of BiH

is still characterized by a multi-layered urban structure, with clearly

identifiable large-scale urbanization of the architectural layer

constructed during the socialist regime. It must be noted that the

1992-1995 war stopped natural development of the city, and created

spatial, cultural, and social gap.

Subsequently, the new additions have a “detached”

trajectory in continuous attempts to reaffirm the identity of Sarajevo

as a more global city. But while contemporary, generic,

decontextualized and eccentric architecture imposes itself as a new

form of violence that results in urban restructuring in general,

representatives of the socialist architecture, are still dominating the

image of a city. Their scale, monumentality, and intelligence of urban

footprint, particularly within the residential areas Alipašino

polje and Ciglane, allows them to maintain their authentic visual and

spatial character and quality, regardless of obtrusive interference of

contemporary additions, that threaten to architecturally pollute

them.

Marijn Dvor, the area proposed as the “new center” by

the masterplan of Juraj Neidhardt, confirms is role as symbol of

renewal and urban experimentation with continuous investments and

efforts for creation of new and contemporary architecture, while on the

other hand it continues the reevaluation of the architecture of the

past. In this view the public buildings, symbols of the socialist city

constitute not only a historical memory but become icons that attend to

stimulate the urban development in many aspects and that for this

reason must be preserved from the neglected.

Since 2007 the Sports and Culture Centre Skenderija hosted the Art

Depot, a temporary location for the Ars Aevi Collection made by the

contribution of the most significant artists of the world, who

contributed with their works to the creation of the collection of the

future Museum of Contemporary Art. It was a way to contrast the

violence of the war of the 90s through the culture, together with the

Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, that covers the history of

the country from the Middle Ages to the present and stands as an icon

of resilience. Regardless of the poor condition and malfunctioning, it

is still one of the most significant city landmarks, that is strongly

etched in the urban memory of Sarajevans.

Sarajevo, is therefore an exemplary case of the exceptional work of

socialist Yugoslavia leading architects, evident through a unique range

of forms and modes easily identifiable along the west-east city axis.

The belated recognition of the value of the works of socialist

Yugoslavia, was confirmed with the exhibition curated by Martino

Stierli and Vladimir Kulić, entitled Toward a Concrete Utopia. Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980 which

took place in New York at the Moma, Museum of Modern Art, in 2018, in

which Sarajevo has been represented through Juraj Neidhardt’s

works.

The works cited, together with many others that have not been

discussed in this paper, constitute nowadays pieces of an open-air

museum that still emits the glimmering radiation of the socialist

utopia, and stand as a testimony and as a reflection of a fragment of

history that characterized the socialist society and system.

Note

* This paper is outcome of the researches and reflections of the

authors conducted within a series of academic activities. In detail: S.

Gruosso and E. Zejnilović are the authors of the Abstract; S. Gruosso is the author of Introduction, Public buildings. From instrument of the regime to icons of the contemporary city and The socialist Sarajevo towards the future; E. Zejnilović is the author of Socialist Sarajevo and Modernization of the City- The role of Neidhardt and impact of Le Corbusier on the city and Residential architecture: Ciglane and Alipasino Polje.

Bibliography

DOBROVIć R. ed. (1973) – The Housing

Complex Đuro Đaković in Arhitektura i Urbanizam 94-95.

Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

GRABRIJAN D. e NEIDHARTD J. (1957) – Architecture

of Bosnia and the Way to Contemporary. Državna založba

Slovenije, Ljubljana.

GRUOSSO S. (2017) – “West Balcan Cities

Viaggio a Est. Alla scoperta di una nuova identità europea”.

In: Crossing sightlines:traguardare l'adriatico. vol. 35.

curated by Pignatti L, Gruosso S, p. 62-83, Aracne Editrice, Ariccia,

Roma.

GRUOSSO S. e PIGNATTI L. (2019) – Sarajevo

an account of a city. LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

INVESTPROJEKT (1985) – Alipasino Polje

Housing Scheme. Sarajevo, Oslobodjenje.

JURIć E. T. e ISLAMBEGOVIć V. (2019) – Reinterpretation

possibilities of the Bauhaus ideas – example of conceptual

design of the Ciglane estate in Sarajevo.

In: 100 Years of Bauhaus Scientific symposium “The Influence

Of

The Bauhaus On Contemporary Architecture And Culture Of Bosnia And

Herzegovina”. curated by Jurić E. T, pp. 40-69, Sarajevo:

National Committee of ICOMOS in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

MRDULJAš M. e KULIć V. (2012) – Modernism

In-between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia.

Jovis Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

NEIDHARTD, J. (n.d.) - Zeleni Grad. Oslobodjenje.

NEIDHARTD T. (2014) – Sarajevo,

through time. Nova dječija knjiga, Sarajevo.

PIGNATTI L. (2019) – Modernità

nei Balcani. LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

ŠTRAUS I. (1977) – Nova

arhitektura Bosne I Hercegovine – 1945-1975. Svjetlost,

Sarajevo.

ŠTRAUS I. (1987) – 15

godina BiH Arhitekture 1970-1985. Svjetlost, Sarajevo.

Journal's articles:

ZEJNILOVIć E. e HUSUKIć E. (2018) – Culture

and Architecture in Distress - Sarajevo Experiment.

International Journal of Architectural Research Archnet-IJAR 12(1):11,

11-35.

GRUOSSO S. e PIGNATTI L., DI LALLO F. (2022) – Urban

development and urban icons in the socialist cities: the case of

Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina. EDA, Esempi Di Architettura,

vol. 2022, SPECIAL ISSUE, p. 85-91, ISSN: 2384-9576.

Grad Sarajevo (2023, January 03) - Sarajevo u

period 1945-1991. Retrieved from Grad Sarajevo:

https://www.sarajevo.ba/hr/article/1222/sarajevo-u-periodu-1945-1991-godina.

Opština Novi Grad Sarajevo. (2021, December 10). Penzionisani

arhitekta koji je učestvovao u projektovanju novogradskih naselja

posjetio Općinu Novi Grad Sarajevo.

Retrieved from:

https://www.novigradsarajevo.ba/news/default/penzionisani-arhitekta-koji-je-ucestvovao-u-projektovanju-novogradskih-naselja-posjetio-opcinu-novi-grad-sarajevo-1636552927/.